The Hub of the Scottish Main Lines

FAMOUS RAILWAY CENTRES - 3

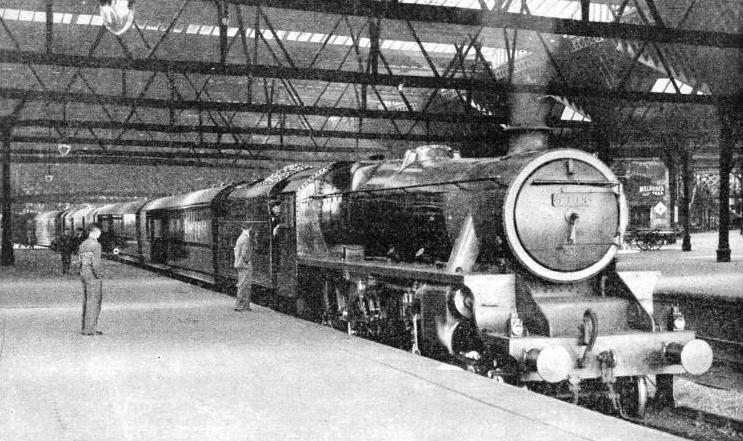

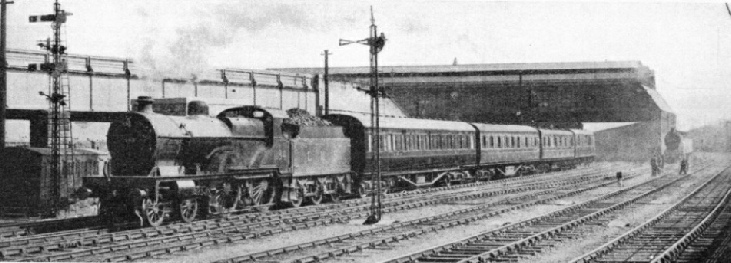

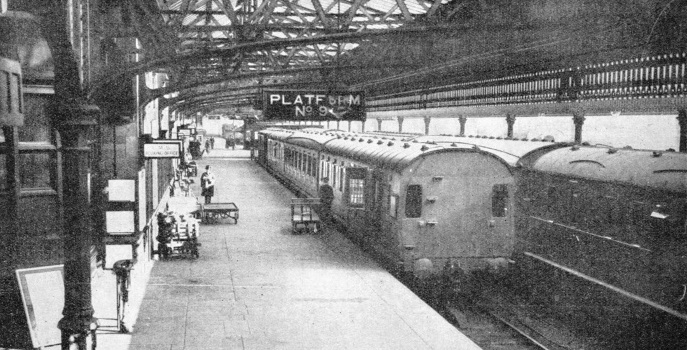

AT THE PLATFORM of Perth General Station. The length of the platform faces totals 7,700 ft. The greater part of the station is covered by a roof of steel and glass. At the head of the train illustrated is seen one of the efficient new Stanier 4-6-0 two-cylinder “mixed traffic” locomotives.

EDINBURGH has the largest Scottish station - Waverley. Glasgow has several large stations; but Perth is the nearest Scottish parallel to York or Crewe. With its one big station, in the middle of Scotland, Perth might be compared to a hand grasping a bunch of reins, the reins being the converging main lines of central Scotland.

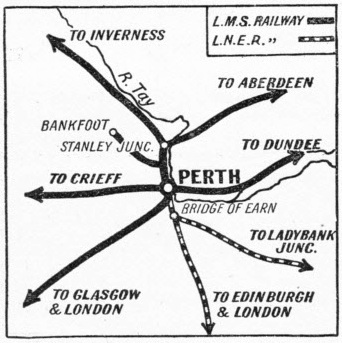

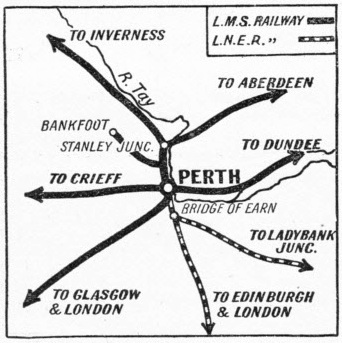

All roads seem to lead to Perth. If the letter X is drawn, and its extremities are marked with the names of Edinburgh, Glas-gow, Inverness and Aberdeen, Perth will be found in the middle of the letter But an irregular X is but the bare skeleton of the railway map of the Perth district; it does not even allow for Dundee, which is one of the largest cities in Scotland. At the present time, the General Station at Perth is used and jointly owned by the LMS and LNER, as successors to the Caledonian and North British Railways. But, before the grouping of the chief British railways in 1923, Perth was used also by the High-land Railway, by virtue of running powers over the Caledonian southwards from Stanley Junction.

A SKETCH showing the railway importance of Perth Station, situated in the heart of Scotland at a point where the main lines converge.

In those days, even to the uninformed observer, Perth General Station was a striking place during its busiest periods, by reason of the variety of the rolling-stock simultaneously visible under its wide glass roof. This variety almost rivalled that of York and Carlisle. First and foremost were the striking trains of the Caledonian Railway - dapper royal blue locomotives with maroon underframes, hauling chocolate-and-white carriages. The North British engines were brown, with red, black, and gold lines, and the coaches a deep tile red. Then there was the Highland, with its engines and carriages green all over, a little lighter than the present Southern Railway colours. On the through expresses from England came the red coaches of the Midland, the West Coast Joint Stock, similar to the Caledonian, the varnished teak East Coast Joint Stock, and, occasionally, maroon coaches belonging to the North Eastern Railway, and chocolate-and-white coaches belonging to the London and North Western Railway.

This variety of rolling-stock serves to show the way in which traffic from all parts of Great Britain has always tended to forgather at Perth. Let us, now, with the aid of the sketch map, have a look at the lie of the land round this great centre. The LMS line from the south via Stirling and Dunblane brings into Perth all the West Coast expresses, which have travelled via Law Junction, Coatbridge, and Glenboig, avoiding Glasgow. The same line is used from Glenboig by the LMS trains from Glasgow (Buchanan Street) and from Larbert by the LMS trains from Edinburgh (Princes Street). Some of these trains terminate at Perth, but others go on to Dundee, Aberdeen, and Inverness. Through carriages from Glasgow go as far as Wick, in the county of Caithness.

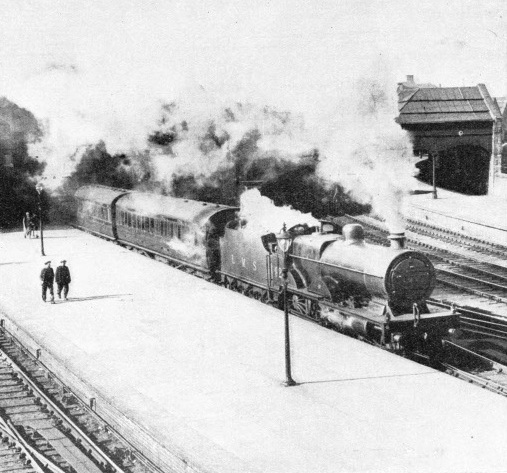

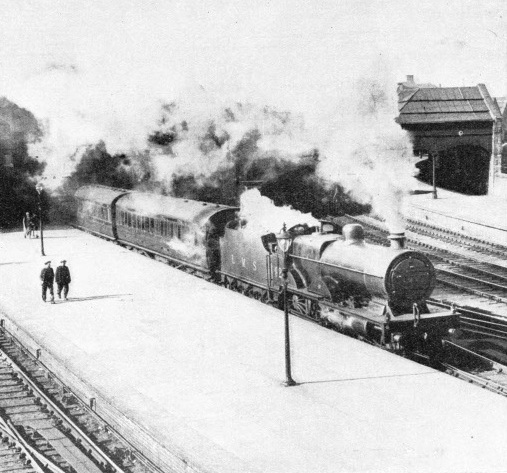

A PERTH-INVERNESS train leaving Perth. The engine is the “Brodie Castle”, with the 4-6-0 wheel arrangement. Immediately behind the engine is one of the comfortable coaches of the former Midland Railway, conspicuous with its clerestory roof.

This is the easy, straightforward entrance to Perth, along the fine open valley of the Earn, into which the line descends steeply from Gleneagles. Trains for Aberdeen, Inverness, and the north run into the main part of the station, but some for Dundee pass into a diverging “wing” on the east side, whence the Dundee line crosses the Tay. It follows the river all the way to its destination. The two important main lines northwards out of Perth - to Aberdeen and Inverness respectively - run as one for seven and a quarter miles to Stanley Junction, but Perth General Station is the interchange point, and acts as the true centre for these lines. Immediately to the north of Perth, on this short line to Stanley, another line bears off almost due west, passing through Crieff (whence a connecting line runs south to Gleneagles) to Comrie and Balquhidder, on the Callander and Oban mountain line. All the foregoing lines belong to the LMS and all, except the Highland main line to Inverness, were formerly parts of the old Caledonian Railway system.

The LNER, as successor to the former North British Railway, enters Perth together with the LMS line from Stirling, which it joins just beyond Moncrieff Tunnel, at Hilton Junction, two miles south of Perth. This LNER line carries the principal traffic of that company from Edinburgh (Waverley) to Perth and Inverness via the Forth Bridge and Kinross, while at Bridge of Earn, three and a half miles from Perth, it is joined by another LNE line which has come in from Ladybank Junction in Fife.

In days gone by, before the Forth Bridge was built, a journey by the North British from Edinburgh to Perth was something of an ordeal. First a local train was taken to Granton, then a ferry across the Forth to Burntisland, and finally a slow train that wandered round Fife until it reached Ladybank. Here it was divided, one part running to Dundee or Tayport and the other to Perth. To-day the LNER provides the shorter route from Edinburgh to Perth.

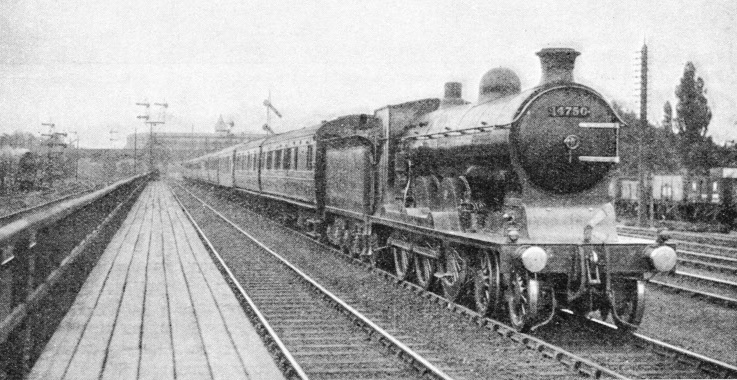

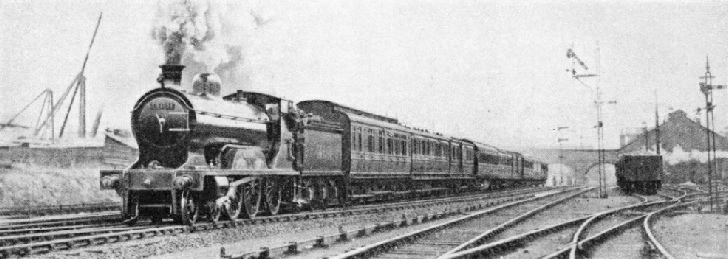

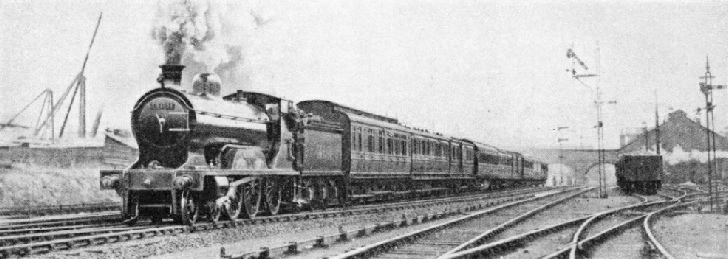

LEAVING PERTH. The 4.30 pm stopping train is seen here just outside the north end of the General Station bound for Aberdeen, eighty-nine and three-quarter miles distant. An early morning train runs non-stop from Perth to Aberdeen in ninety-nine minutes.

LEAVING PERTH. The 4.30 pm stopping train is seen here just outside the north end of the General Station bound for Aberdeen, eighty-nine and three-quarter miles distant. An early morning train runs non-stop from Perth to Aberdeen in ninety-nine minutes.

The LNE line, too, is perhaps the more interesting, for it takes the passenger across the Forth Bridge - always a thrilling experience even when familiar - and then passes through attractive country, past Loch Leven and its island castle, associated with the romantic escape of Mary Queen of Scots in 1568. It then runs to Bridge of Earn through the pleasant valley of Glenfarg.

The LMS line runs through Stirling, an interesting place both to the railway enthusiast and to the historian. In the neighbour-hood of Stirling the magnificent Castle Rock, the Old Bridge across the Forth, and the battlefield of Bannockburn are all clearly visible from the train. So whichever way the traveller enters Perth from the south, he will probably not be disappointed.

Another interesting point about Perth is the fact that the famous named express trains of both the LMS and the LNER can be seen together under the same roof. This is possible also at Aberdeen Joint Station and at Edinburgh (Waverley), though in the latter instance no LMS engines are seen with their train. Elsewhere it does not occur. For instance, the “Royal Scot” and the “Flying Scotsman” both travel between London and Edinburgh, but they use different stations and are at no time within sight of one another. The London termini - Euston for the “Royal Scot” and King’s Cross for the “Flying Scotsman” - are less than a mile apart. The Edinburgh termini are separated by little over half a mile. But during their respective journeys the trains are often scores of miles apart.

But at Perth the traveller may encounter the LMS “Royal Highlander” from Euston, together with the LNER “Highlandman” from King’s Cross. In the slack season, indeed, the LNER coaches are attached to the LMS “Royal Highlander” at Perth, and worked up to Inverness as one train. But before we consider the train service through Perth, we will make a brief study of the General Station itself, for it is a building remarkable in a number of ways.

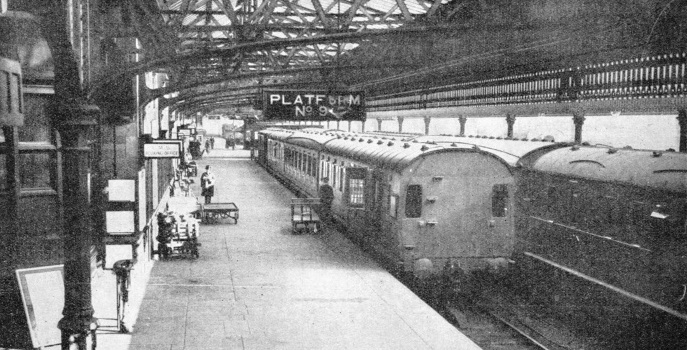

Perth General Station is laid out in a way similar to that of the Waverley Station at Edinburgh; that is to say, it consists of two distinct terminal sections placed end to end, with through lines on either side. There is similarly a modern and well-equipped hotel situated on the up side of the station, but there are additional spur platforms bearing away from the up side and serving the trains on the Dundee line. The total length of the platform-faces at Perth General is 7,700 ft, which is in excess of the totals boasted by Carlisle, Willesden Junction (Low Level), and stations at a number of other important centres. Perth Station might, perhaps, be described as having a huge island platform, split up into forks at either end.

The offices, refreshment-rooms, and waiting-rooms are in the middle of the island, the greater part being covered by an all-over roof of steel and glass. Ramps and footbridges connect the island with the outside approach and with the hotel, as also with the Dundee line platforms. The terminal lines at the southern end of the station accommodate the LNER trains from Edinburgh and Ladybank Junction; those at the northern end form the starting point for Highland and Caledonian Section trains, mostly of the stopping order, which serve Blair Atholl, Aviemore. and Inverness (Highland Section), and Crieff, Balquhidder, Arbroath, Forfar, and Aberdeen (Caledonian Section). Blair Atholl and Balquhidder form the terminal points of a number of local trains serving all intermediate stations, though these cannot, by any stretch of the imagination, be classed as Perth’s “suburban service”, traversing as they do considerable stretches of beautiful Highland scenery.

The through lines on the west side accommodate all the best northbound expresses for the Highland and the Aberdeen lines, though when traffic is really heavy the northbound “Royal Highlander” has been known to run in on the eastern or “up” side, which at first sight seems a rather peculiar proceeding. From the spur platforms on the east side of the station, another local service, more or less self-contained, is operated by the LMS to Dundee via the direct line, and this includes both stopping trains and lightweight expresses.

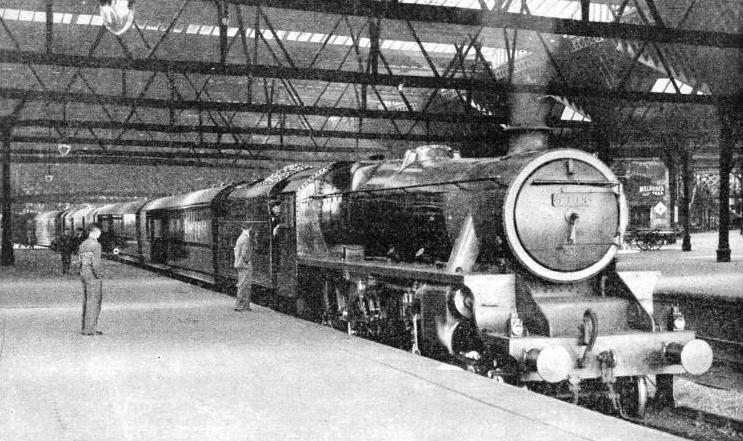

AN ABERDEEN-GLASGOW express departing from Perth for the south. The train is hauled by a 4-6-0 inside-cylinder locomotive of the former Caledonian Railway.

During the past few years a famous engine was often seen at the head of one or other of these local Dundee expresses. This was the ex-Caledonian 4-2-2 locomotive No. 123, which made history in the “Race to the North” of 1888. No. 123 eventually became LMS No. 14010, and survived to be the last single express engine in Great Britain. Some years ago this graceful single-wheeler was drafted to the duty of working the Caledonian Railway’s official inspection saloon, a task which she continued to perform after the LMS took over. The time came, in 1930, when No. 123 grew too old to remain in service much longer. She had, however, to complete a certain mileage before she could be withdrawn, and it was decided that the lightly loaded local expresses between Perth and Dundee would suit her admirably. So in her later years this veteran of the “Race to the North” suddenly reappeared on important express passenger work. This fact appealed to the imagination of many railway enthusiasts, old and young. There was an agitation in favour of her preservation, and at last the LMS announced that, when she came to be withdrawn, she would not be broken up, but preserved in honoured retirement. This has now come to pass, and No. 14010 has retired to St. Rollox works, at Glasgow.

Some of the LNER locomotives working the local trains into Perth from Ladybank Junction formerly belonged to the North British Railway, and are also one-time racers. Among them are engines that used to run from Edinburgh to Aberdeen during the “Race to Aberdeen” of 1895. Perth General Station might therefore be described as a sort of Valhalla for old locomotive warriors. It is certainly an impressive sight to see the veterans alongside the fine modern “Royal Scots”, the LMS compounds, and the new taper-boilered engines of Mr. W. A. Stanier’s design, which now work most of the principal LMS expresses in all directions from Perth.

Perth General Station is sixty-three and a quarter miles from Glasgow (Buchanan Street), eighty-nine and three-quarter miles from Aberdeen, 118 miles from Inverness (via Carr Bridge), twenty-one miles from Dundee, forty-seven and three-quarter miles from Edinburgh (Waverley) and over sixty-nine miles from Edinburgh (Princes Street).

Heavy Night Traffic

Thus the LNER has a considerable advantage where the Edinburgh traffic is concerned, since the LMS has to make a detour via Larbert, avoiding the Firth of Forth. The LMS, on the other hand, monopolizes the main line traffic between Perth and Glasgow, there being no direct LNER line between these two cities. By the West Coast route, Perth is 449¾ miles from London (Euston). By the Forth Bridge and the East Coast route, the distance to London (King’s Cross) is 440¾ miles, nine miles shorter than the West Coast route in spite of the bold sweep outwards along the north-east coast between Edinburgh and Newcastle-on-Tyne.

There are no fewer than three locomotive depots adjoining the General Station, two of which belong to the LMS Railway. The first and largest is that which formerly belonged to the Caledonian Railway, situated near the point of junction with the LNE line. Here are stationed the locomotives which work over the LMS lines south of Perth, the Dundee line, the Crieff and Balquhidder line, and the Aberdeen line. Beyond the northern end of the station is the second LMS shed, originally that of the Highland Railway. The engines stabled here work exclusively to Blair Atholl, Aviemore, and Inverness. Thirdly, there is the LNER shed, at the south end again, but nearer to the station than the old Caledonian shed. This is not a very large shed. Altogether the total number of locomotives housed at Perth is fairly large. There are extensive sidings for the storage and marshalling of carriages and wagons belonging to both companies.

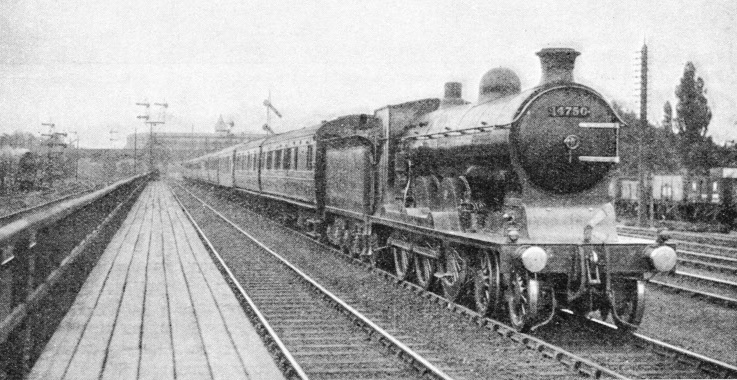

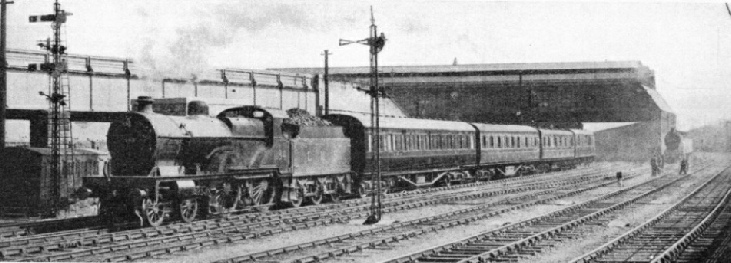

PERTH GENERAL STATION is to-day owned and used by both the LMS and LNER. Here is an LNER train leaving Perth for the south.

It is difficult to say when, exactly, Perth General Station begins its working day. One might almost say that it begins the night before. The reason for this somewhat cryptic statement is that Perth really starts the day with a night service to Inverness, a practice which has prevailed ever since the ‘eighties of the last century. Only what was then the 12.40 Parliamentary train, stopping at all stations, is now the 1.15 sleeping-car express. Three minutes before eleven, the night before, there is due the 9.30 London and North Eastern express from Edinburgh (Waverley), which connects with the 1.20 pm East Coast express from King’s Cross. This train brings in East Coast and Edinburgh passengers tor the night connexion to Inverness and Northern Scotland. The time, 10.57pm, is long before 1.15 am, but the wait need not be tedious.

The passenger may either have a late supper in the hotel or the station dining-rooms, or he may enter one of the Inverness coaches which stand in the down Highland bay and settle down for the night. These coaches do not comprise the whole of the night train to the north, but are provided to spare the Edinburgh-Inverness passengers the unpleasant business of hunting for seats in the already filled coaches of the through train from Glasgow. This train, preceded at 12.10 am by a train from the south, with through carriages from Euston to Aberdeen, comes in at 12.25 am, having left Buchanan Street at 10.45 pm. The 10.45 from Glasgow is a comprehensive train; for, in addition to being the night Highland express, with a first- and third-class sleeping-car from Glasgow to Inverness and through carriages from Glasgow to Wick (regularly) and Kyle of Lochalsh (in summer), it also contains a considerable section destined for Aberdeen, which will be reached at the uninviting hour of 3.0 am, with one regular and two conditional intermediate stops. Scottish people seem to enjoy travelling by night, and all the sections of the train are adequately filled.

During the night hours, therefore, Perth General Station is almost as full of activity as its English counterpart, Crewe. For the next fifty minutes after the arrival of the express from Glasgow, the station is filled with the noises of shunting and the roar of escaping steam, while the train is divided, the Aberdeen portion sent on to its destination, and the Highland section united with the waiting coaches in the bay platform. Eventually, two big Highland locomotives are attached to the complete train, which is now of caravan length. The Highland express puffs out into the darkness and moves away to the north. Perth’s day has begun.

After this vigorous beginning, the station quietens down tor a little while. The station reawakens, however, before the morning is far advanced. At 4.45 the up night express from Inverness to Glasgow comes in from the north, and this early morning arrival heralds considerable activity on the down side of the station as well. Round about August 12, the early morning passenger traffic northwards through Perth is astonishing. At 4.50 am the sleek crimson length of the “Royal Highlander”, which left Euston at 7.20 the night before, glides into the station. In the normal course of events, the “Royal Highlander” is divided, one half being dispatched to Inverness and the other to Aberdeen, the former section taking with it the “Highlandman”, which has come in five minutes later.

But, as we have seen, these services expand out of all recognition during the height of the season, when the station may be faced with five or so “Royal Highlanders” and perhaps two full-length “Highlandmen”, all of which have to be provided with fresh engines and sent on their way with as little bother as possible. It is a stirring sight to see all these great trains coming and going, one after another, in the cold sunlight of the early morning. Breakfast cars are added to them at Perth.

STEAMING SOUTH. This express is hauled by a 4-4-0 “Crimson Rambler” class engine of the type formerly standard on the old Midland Railway. Over 200 of these successful locomotives are now in use over all parts of the LMS system.

Some of the passengers are still asleep. Others, often accompanied by their dogs, come out on to the long platform and parade up and down, refreshed by the beautiful air which blows down from the mountains. At the head of their train, perhaps, “Gordon Highlander” is being replaced by “Brodie Castle” and “Clan Munro”. Double-heading of the heavier trains is the usual practice on the long, uphill journey from Perth to Drumochter Pass, and the two engines usually work through to Aviemore together. Though we have mentioned a “Castle” and a “Clan” in the present instance, most of the heaviest work over this section of the Highland line is now operated by Mr. Stanier’s fine 4-6-0 “mixed traffic” locomotives, assisted by ugly, though efficient, 2-6-0 engines introduced during the late nineteen-twenties. It is to be hoped that, sooner or later, the new engines will be invested with appropriate Highland names, as were their older partners.

At 5.33 there arrives yet another Highland express from Euston, whence it started at 7.30 the previous night. Leaving at 6.25, this will reach Inverness at 9.50, sixty-five minutes after the initial “Royal Highlander”; while a section of it, detached at Aviemore, will run round the old Highland main line by Forres and Nairn. Not unnaturally, when the “Twelfth” rush is on, these timings tend to go by the board, and the company’s special notices and handbills must be used to qualify the statements contained in “Bradshaw”. By the time the Aberdeen and Inverness expresses - or, rather, the first batch of them - are comfortably out of the way, the General Station has shaken down thoroughly well to its day’s work.

Turning once again to the Aberdeen line, we find the 6.13 running to Aberdeen without an intermediate stop, accomplishing the journey of eighty-nine and three-quarter miles in one hour thirty-nine minutes. This is a remarkably fine run, for the route is anything but easy in a number of places. The 6.13 am from Perth carries the Aberdeen mail-vans off the “West Coast Postal”, leaving Euston at 8.30 the previous evening. It was on the Perth-Aberdeen line, incidentally, that the old Caledonian Railway once operated the fastest booked run in Great Britain, between Forfar and Perth, over thirty-two and a half miles in thirty-two minutes. That was a long time ago, and even before the war of 1914-18 it had been beaten by the North Eastern Railway booking of the Newcastle-Sheffield express between Darlington and York. For all that, it remained the best run in Scotland.

Unceasing Activity

Naturally, the trains running northwards out of Perth over the Highland section are considerably slower than those running on the old Caledonian lines, for they encounter long ruling gradients in the neighbourhood of 1 in 70, which render high speeds out of the question. Mountain railways have few, if any, stretches of straight line over which an engineman can “let her go”. The 3.45 pm from Inverness to Perth covers the thirty-five and a quarter miles from Blair Atholl to Perth in fifty-six minutes, with one stop at Pitlochry. An attempt to cover the distance over that tortuous route down the valley of the Tay in “even time” would be enterprising, but probably suicidal in the circumstances.

It will not be possible to analyse the entire train service which passes through Perth in the round twenty-four hours, though we have seen the spectacular way in which the day begins. The busy hours follow one another all day, and in the evening the great expresses from the north to Edinburgh, Glasgow, and London come gliding in on one another’s tails, just as the down trains did in the early morning. But it can be truthfully said that there are few things so spectacular as that spate of sleeping-car expresses which surges through Perth from 4.50 am onwards during the August holiday season.

In the old days, before the general introduction of restaurant cars, the morning stop at Perth used to be of greater significance, even, than it is now. For then it provided the “breakfast interval”. Many passengers, too, used to take in breakfast baskets there, containing hot ham-and-egg meals. Queen Victoria, on her journeys to Balmoral, used to breakfast in state at Perth.

These conditions of railway travelling have passed away for ever, though it is only comparatively recently that restaurant cars have made their appearance on the northern lines of Britain. Now that they are established, they are found, on the Highland Section of the LMS, even on the stopping trains.

A GENERAL VIEW of one of the platform bays at Perth Station. The lay-out of the General Station at Perth bears a close resemblance to that of Waverley Station, Edinburgh, with a similar semi-terminal design. Additional spur platforms on the up side of the station are provided for passengers on the Dundee line.

You can read more on “Carlisle Station”, “The Railways of Caledonia” and “Scottish Mountain Railways” on this website.

LEAVING PERTH. The 4.30 pm stopping train is seen here just outside the north end of the General Station bound for Aberdeen, eighty-

LEAVING PERTH. The 4.30 pm stopping train is seen here just outside the north end of the General Station bound for Aberdeen, eighty-