From Europe to the Far East by the World’s Most Cosmopolitan Train

BITTER COLD AND TROPICAL HEAT are met with on the Trans-Siberian journey. This picture shows a wintry scene near Omsk, in Siberia.

OPINIONS differ about the “Trans-Siberian Express”, particularly among people who have never seen it. Those who dislike Russia talk about a slow, patched, dirty old train that creeps from Europe to the Ear East, while its progress is interrupted by breakdowns. Those who have an extravagant admiration for the land of the Soviets maintain that it is the most magnificent train in the world. It is neither; but it is one of the most remarkable trains in the world, and is more spectacular than the great transcontinental trains in the United States of America.

Before the war there were two Trans-Siberian services, one in which the cars were provided by the International Sleeping Car Company, and one conducted by the Russian Government. The rolling-stock of both trains was superb; perhaps the International cars were the more comfortable, though they were distinguished by that degree of ornateness - peacock-blue plush, scroll work and gilding - which is now out of fashion. In those days there was a church on the train, or, rather, a carriage fitted as a Russian Orthodox chapel. During the Revolution of 1917 the International Sleeping Car Company’s rolling-stock was confiscated by the Soviet. Under its present owners it still does duty on the main lines of Russia and Siberia, though in recent years the Ways and Communications Commissariat have introduced a number of modern vehicles not unlike those of the Mitropa Company in Germany.

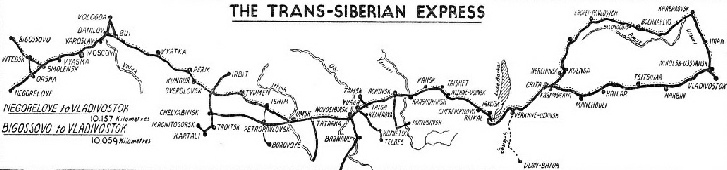

A previous chapter described how the “Orient Express” connected Western Europe with the Near East. Russia is not Western Europe, but it is still European, and from it the Trans-Siberian goes out to the Middle East of Central Siberia and Northern Tartary, and the Far East of Mongolia, Manchukuo and across a strip of water - Japan. Some years ago it was said that the railways and steamers of the CPR took one “westward to the Far East”. The “Trans-Siberian”, with the steamship lines across the North Pacific, will equally well take one eastward to the Far West. The railway journey from Moscow to Vladivostok takes from nine to ten days at the best.

Time could then be saved by travelling southward from Karimskaya through Harbin on the Chinese Eastern Railway (sold in 1935 by Russia to Manchukuo), rejoining Soviet territory just before reaching Vladivostok. The Chinese Eastern, however, besides being a bone of contention for a number of years between Russia and Japan, was rather afflicted by train bandits and wreckers. If a traveller wanted to feel safe, he went all the way round by Khabarovsk. If he wanted a more interesting journey, he risked the Chinese Eastern. Now the CER connexion is for China only. This Chinese Eastern Railway was built by the Russians, and was maintained by them for years. It is constructed to their own broad gauge (five feet), and the locomotives and rolling stock are of typically Russian design.

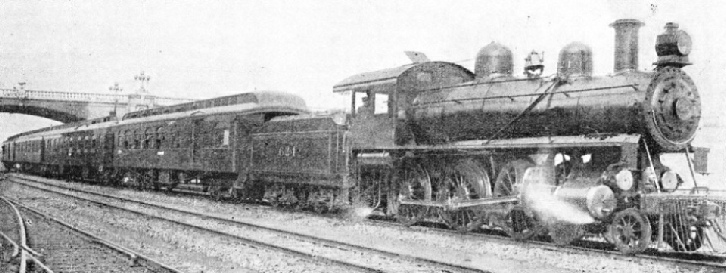

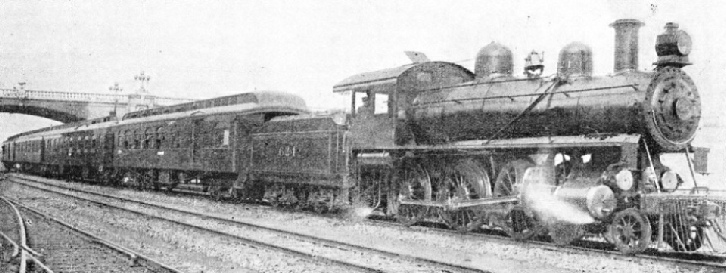

Russian locomotives look most unusual to British eyes. Not only is the rail-gauge a few inches wider than that of the British, but the construction gauge is also much greater, permitting the building of wide, roomy coaches and locomotives with a height of no less than 17 ft from rail to chimney-top. The biggest British engines are 13 ft 6 in high. Another feature of Russian locomotives is the railed-in gallery communicating with the cab by “front doors” in the weather-board, which runs round the boiler and smoke-box. The cabs are closed in against the rigours of the northern winter, all modern engines and many old ones having a covered flexible “vestibule” between the cab and the tender, so that the enginemen are completely shut in. Some of the locomotives, too, are of strange appearance, with balloon smoke-stacks and an assortment of gadgets all over their exteriors.

The modern express engines, however, when the traveller becomes accustomed to their tall, spread-out aspect, are rather striking, especially if they are kept clean by enthusiastic enginemen. A driver with an excellent record in Russia may be rewarded by having his engine named after him.

The quickest way to join the “Trans-Siberian Express” is to travel through Germany and Poland, but if the traveller wants to see a little more of the people, he should take a Russian ship from London to Leningrad, and travel down the October Railway to Moscow. At Moscow one is deep in the unfamiliar. The city, with its domed Byzantine buildings alternating with ultra-modern workers’ flats and offices, is an extraordinary blend of East and West. Sometimes it reminds one of the squalid splendour of old Bagdad, and sometimes it seems more like some caricature of America with a little of Germany included. Everywhere it is crowded to desperation. The old buildings are dirtily picturesque; the new ones, emblems of a new age. At Moscow the “Trans-Siberian” waits to begin the first lap of the long journey, which will be concluded at the Sea of Japan many weeks before the steamship.

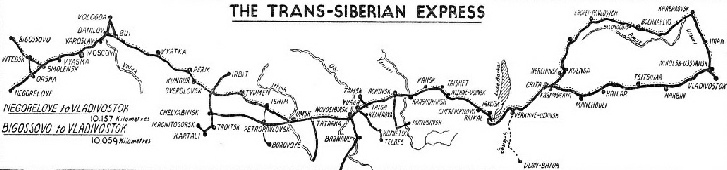

THROUGH SOVIET RUSSIA and the land of the Tartars, across the Steppes and on to China and Japan, the Trans-Siberian express takes from nine to ten days to complete its journey.

On the platform surges a cosmopolitan crowd. Bearded, woolly-capped Russians of the old school; lean, unsmiling and desperately earnest Communist students, about to travel out to some Siberian industrial or research centre; a sprinkling of curious tourists, some from England, some from Germany, and some from America; birdlike, observant Japanese; inscrutable Chinese, and the heavy, Mongolian types of Siberian Tartary. The women are as widely differing as the men, and may vary from sharp-featured young Communists, off to study collective farming, to queer old women with shawls over their heads, returning to some country district in which, up till now, they have spent all their lives.

The train consists not of first- and second-class, but of “hard” and “soft” coaches, all of which have sleeping-berths. Those of the “hard” class have wooden berths, but a mattress and bedding can be hired from the conductor.

If, however, the traveller dislikes crowding, noise, smells and insects, he will be advised to travel “soft”, less interesting as it may be. There he will find tourists, specialists, and what has been called the “portfolio class”. For in Russia, “class” is a forbidden word, and young men travelling in cushioned ease are nervous and offended if asked why they are not travelling “hard” with their fellow-citizens. So if the traveller wants peace and quiet, he will be wise not to discuss politics.

A SOVIET LOCOMOTIVE. One of the most striking features about Russian engines is their unusual height. They are 17 ft from rail to chimney top. The biggest British engines are 13 ft 6 in high. This photograph shows a standard 2-6-2 express locomotive, built for the Russian 5 ft gauge.

Before the train moves off at 5.45 pm on a Monday evening, a glance at the locomotive is worth while. At the head of the train she stands, a rather long-legged 2-6-2, with the usual gallery all round, painted green, and perhaps bearing a large ornamental star on the smoke-box door. This is the standard express passenger type of the present Soviet railways, though there are many smaller 4-6-0 engines, and larger machines of the 4-8-0 and 2-8-4 wheel arrangement. The last-mentioned are the finest in appearance in the Union, though the 2-6-2 has something of the aspect of a very tall coach horse. On the heavy coal trains from the Donetz Basin will be found the largest locomotives in Russia - among the largest in the world - one class having the 4-14-4 wheel arrangement, while there is also the great 4-8-2 and 2-8-4 Garratt engine built at Manchester, the largest yet constructed in England. But such engines as these will not be found on a Trans-Siberian passenger train.

If the train is in good condition, the traveller will find the “soft” compartment very comfortable. It contains two berths, the lower one of which is placed transversely, as in Great Britain, and the upper, on the side away from the corridor, long-itudinally, as in America. It is a good arrangement, as it gives more headroom. The whole compartment, too, is much more spacious than is possible with the restricted loading gauges of Western Europe.

One peculiarity of Russian travel, however, is apt to be embarrassing, for the traveller never knows who may be sharing the compartment for days and nights. The writer heard of an Englishman who had to travel half-way across Siberia with a lady he had never seen before. When she left the train, the Englishman was greeted by a Russian, who kissed him on both cheeks and thanked him “for taking care of my wife on the road”.

Strange Travelling Companions

The “Trans-Siberian” is not a fast train. Those who run it know that it has plenty of time in which to beat the fastest liner, that goes by way of Ceylon and the Straits. The very long waits at some of the cities give a respite from the rolling of the cars. Usually, the traveller feels very tired after the first thirty-six hours, after which he gets his “train legs” and enjoys the rest of the journey. The first meal in the restaurant car is interesting. In addition to the strange food, which can be very good, the traveller is cheek-by-jowl with a representative selection from the cosmopolitan crowd seen on the platform.

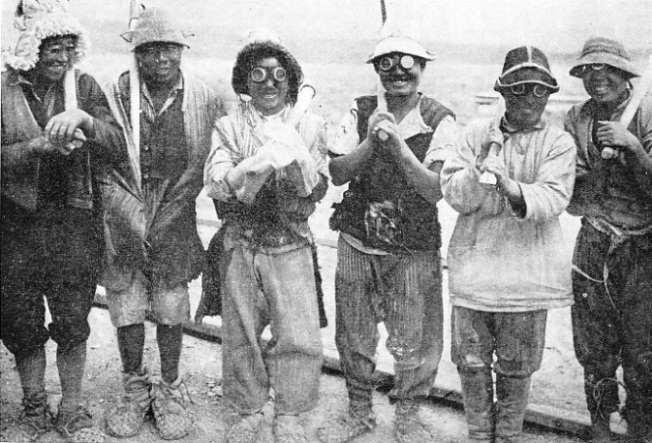

ASIATIC RAILWAY WORKERS examining the points on a stretch of track in Manchuria.

He may share a table with a Chinee, a mining engineer bound for the Lena Basin, and someone whose activities are devoted to the extermination of wolves. If he passes one of the “hard” cars, he will have another surprise. A gangway runs down the side, like a corridor, but not divided from the rest of the car. Each division has six transverse berths, three on each side. Into such a division may be seen a family of ten crowded with their bundles and cooking utensils. In the side gangway, passengers may be squatting, drinking tea, eating or sleeping. Also, it is not unlikely that the entire car may be lighted by candles, stuck on to shelves or mouldings by their own wax. In recent years, however, electric lighting has made considerable strides on the Russian railways, though before the war candles were the standard lighting on all but the very best cars.

After dinner the traveller returns to his compartment and, sooner or later, turns in while the train rumbles into the valley of the Volga. The river is crossed about two-thirds of the way from Moscow to Kazan by the old direct route to the Urals, or before reaching Bui on the Viatka line, which is now always traversed. The through Leningrad-Vladivostok cars join this main line at Bui, and most passengers travelling by way of the sea route from England arrive by them. This northern line passes through Perm, and the two are united at Sverdlovsk (formerly Ekaterinburg), the capital of the Ural district and the first important Siberian town.

The first stretch from Moscow has, perhaps, been a rather dreary progress over endless, plate-flat prairies, when night travelling is to be welcomed; but the crossing of the Urals is remarkably beautiful, especially in late spring, with the great hills rising in majestic folds above the wonderful woods of fairylike silver birch. Later on, when passengers are getting tired of the pines and larches of Central and Eastern Siberia, they will think of, and hanker after, those lovely birch-woods in the Urals through which the train creeps so gently as it climbs the western slopes. Although, on the other side of the range, Sverdlovsk is the capital of a new industrial area, these untouched Ural forests are just as they were before the dawn of civilization; utterly wild, leafy, and inhabited by deer, bears and wild pig; a green paradise in late spring and summer, a golden paradise in autumn, and a white “ghost land” in winter. In altitude, the Urals are reminiscent of parts of the Scottish Highlands. It is hard to realize that the range is considerably in excess of a thousand miles in length.

At Sverdlovsk, 1,300 miles from Leningrad, there is a long wait, and the exploring passenger has a chance of examining life in the first Siberian city. Since it lost its old name it is apt to be forgotten that this is Ekaterinburg, where Nicholas, Tsar of All the Russias, and his family were killed in a cellar on July 16, 1918.

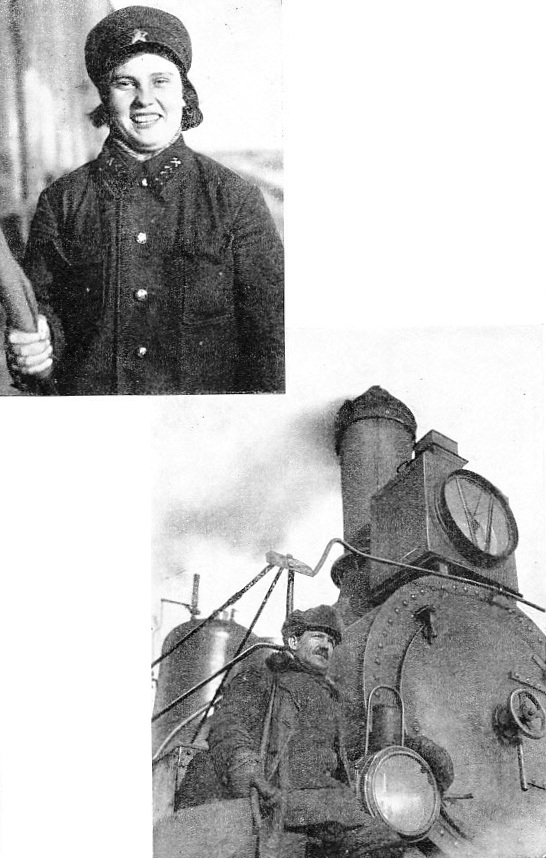

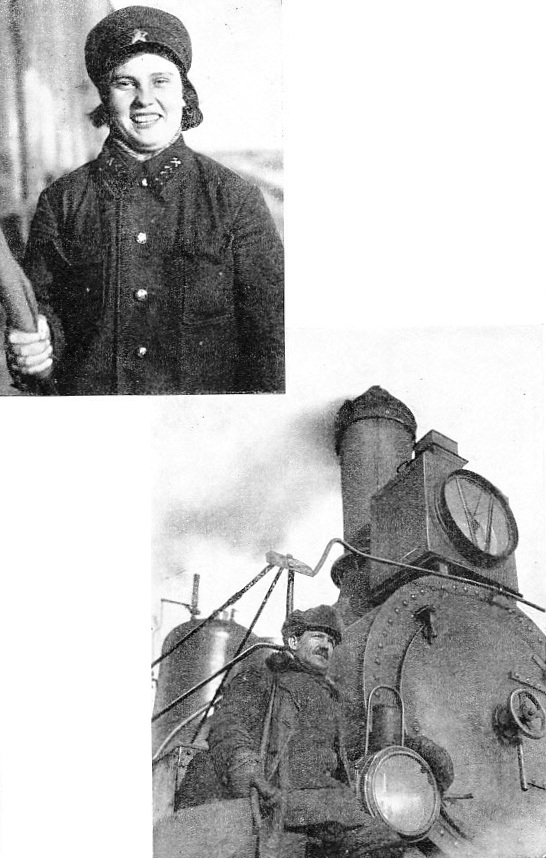

THE FIRST STATION-MISTRESS in Soviet Russia was Nina Maljarenko. After seven months’ intensive training on the Tomsk railway in Siberia, she was appointed station-mistress at Kolonija, on the Omsk line.

A DRIVER with a good record in Soviet Russia is sometimes rewarded by having his engine named after him. This photograph shows a typical Russian engine-driver. Several types of locomotives operate on the Soviet railways, and among them is a Garratt engine built in England.

Leningrad brings a welcome change from the restaurant-car food to eatables that can he bought from the stalls on the platform. The traveller can drink Russian tea from the great samovars and enjoy a cheap luxury in the form of caviare. After a time he will have eaten enough caviare to be surfeited. Now that he is in Siberia it is possible that bear-steaks will figure on the next menu.

From Sverdlovsk the old main line strikes southwards to the city of Cheliabinsk, but nowadays the Trans-Siberian Express keeps northwards, calling at Tyumen at 2.50 in the afternoon of the third day, counting the evening of the departure as the first day on the journey. Here the train waits but five minutes. Late in the afternoon it crosses the River Tobol, about 160 miles south of Tobolsk, and runs to Omsk, 558 miles on from Sverdlovsk, at 3.42 am on the fourth day. Omsk is a fine and important city, with a population of over 135,000, and a cathedral, in the bulb-towered Russian style, which acts as a landmark for many square miles of the surrounding Steppe country.

The place owes most of its development to people banished to Siberia in Tsarist days, for they included many who were allowed their freedom on condition that they never returned over the Urals.

Mere banishment to Siberia was not such a terrible thing as condemnation to a convict life in the salt mines. Those banished were so treated usually because they held opinions of which the Government disapproved.

It is at Omsk that we finally rejoin the old main line across the Urals, which has come through Cheliabinsk and Petropavlovsk.

Hereafter comes a dull stretch across the seemingly endless Steppes. The Irtish River is crossed, and the train plods away over the great, flat lands until at six minutes past four in the afternoon, just over twelve hours after having left Omsk, it rolls into the Steppe town of Novosibirsk.

Novosibirsk might be dismissed as dirty, but it is not so bad as Krasnoyarsk, farther on. Also, it is interesting as the junction with the Turksib Railway, which runs right down into Turkestan.

The Turksib was opened throughout in 1929, to the accompaniment of considerable enthusiasm; but, as a matter of fact, a good part of it, including that which runs into Novosibirsk, is quite old.

If the Turksib train is in the station the traveller will probably see a line of crammed but otherwise undistinguished coaches, headed by an antiquated 4-4-0 locomotive.

As the Trans-Siberian rolls out into the Steppes again, it crosses the Turksib line by a lattice girder bridge forming a fly-over junction. At Taiga, reached at 9.37 pm, we are at the junction for Tomsk, the branch line running off to northwards. After leaving Achinsk, the next important halting place after Taiga, the train crosses the Chulim, a tributary of the great River Obi, which it passed just before Novosibirsk, and at 9.21 on the morning of the fifth day we are at Krasnoyarsk.

This is not a praiseworthy place, but it is, for all that, an important centre, and there is a good deal of interchange traffic with the river steamers which paddle down the mighty Yenisei into the desolate tundra country of the far north.

In the Heart of Siberia

All day and all the next night the Trans-Siberian rumbles on through the grand primeval forests which lie to the north of the Altai Mountains, calling at Nizhne-Udinsk last thing at night, and running into Irkutsk at 12.22 in the middle of the next day.

Irkutsk is worth exploring, even in the forty minutes during which the train waits. It is, perhaps, the finest city in Siberia, and has something definitely metropolitan about it, with a magnificent cathedral and streets and an opera house which have been described as “worthy of Paris”. As with Omsk and many of the cities of Siberia, Irkutsk owes its being to the enterprise of those who, in former years, were banished from Holy Russia on account of their opinions. The city has a population of about 822,000, it is a district Soviet headquarters, and is the finest Russian town in Asia. It is also the headquarters of the Middle-Asiatic Division of the Soviet Railways, which comprises 2,773 miles of railroad all built to the 5-ft gauge.

The country here has undergone a change; and a welcome change it is, too, after the interminable Steppes. For after following the River Angara out of Irkutsk, the train reaches that inland sea known as Lake Baikal, over which the trains used to be ferried in the old days before the avoiding line was built.

In winter, rails were at one time laid on the frozen surface of the lake. Now the line is carried through a magnificent series of rock cuttings and tunnels round the southern corner of the lake. It is called a lake, although it is 300 miles in length, from north to south. The country is grandly mountainous, with wild, shaggy forests of cone-bearing trees and beautiful forest and Alpine flowers; everything far more spectacular than we have seen hitherto.

THE STEPPES are vast grassy plains, and seem an almost endless part of the Trans-Siberian journey. They are not, however, uninhabited, and at one part of its trip across the Steppes, the Trans-Siberian stops at Omsk, an important city with a population of more than 135,000.

The train twists and turns along the shores of the lake, passing on its journey through no fewer than forty-two tunnels, waking the silences with an occasional deep note on her whistle. The traveller watches the scenery until nightfall, feeling that this more than compensates for the past monotony of the Steppes.

The line is running roughly parallel to the Chinese frontier on the southern side, and Yablonoi Mountains on the north, when, at a quarter-past one in the middle of the seventh day, the train runs into Chita. Though the Trans-Siberian has been in Asia for days, it has not seemed like it, somehow, up till now. But something about Chita makes the traveller feel that he has travelled very far eastwards. He is among the Mongolian peoples of Eastern Siberia; yellow-skinned they are, squat nosed and almond-eyed. Chita is 4,049 miles from Leningrad, and the Trans-Siberian has taken roughly a week to reach it. By now, when it is almost in China, the steamer from London may still be in the Red Sea.

At Karimskaya, sixty miles farther on, we are at the junction for the Chinese Eastern Railway, and down it, twice a week, the Trans-Siberian makes its way to Harbin, for Pekin. The frontier is crossed a little to the north-west of Manchouli, and headed by a Chinese Eastern locomotive, which is an ordinary Russian one so far as appearances go, the train climbs over the Khingan Mountains after having skirted the great Gobi Desert, a vast and desolate waste inhabited by those queer, rabbit-like creatures called prairie dogs, and little else.

THE SOUTH MANCHURIAN EXPRESS passing under the Nippon Bridge. This famous train connects with the Trans-Siberian railway at Harbin. Each compartment has hot and cold running water and can be turned into a sleeper with accommodation for two people.

The train takes just two days to reach Harbin, so long as there are no rail-lifting brigands in the way, and on the morning after its arrival the connecting train leaves for Pekin via Changchun and Mukden, taking another twenty-four hours over the journey. It is probable that in the not-too-distant future, the Chinese Eastern Railway will be converted to standard gauge, and a single Japanese-owned train will make the journey from Manchouli right through Manchukuo to the old Chinese capital.

Back in Soviet territory, the “Trans-Siberian” moves off from Karimskaya on its long, brigand-avoiding run round the frontier, following the vast valley of the River Amur all the way to Khabarovsk, no fewer than 1,384 miles farther on, and taking another day and a half on the journey. This last part of the journey seems to carry us through a “Back-o’-Beyond”, and, indeed, we are nearer America than familiar Western Europe. From Khabarovsk, where, once a week, the train terminates, the through express runs southwards, paralleling the Manchukuo frontier all the way, over the remaining 478 miles of its long journey, calling at Nikolsk-Ussurusk, and finally running into the Pacific port of Vladivostok, which is 5,971 miles from Leningrad, at three minutes past eleven at night on the ninth day out.

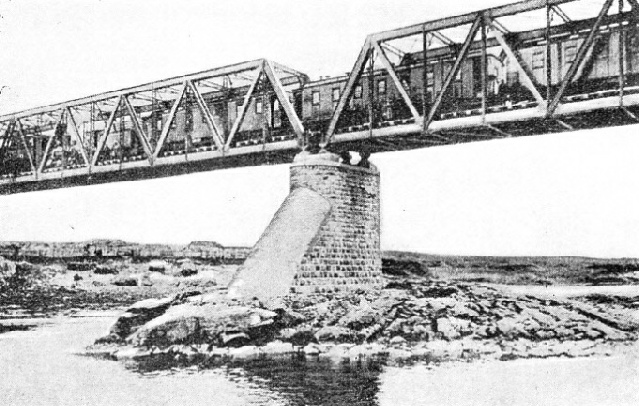

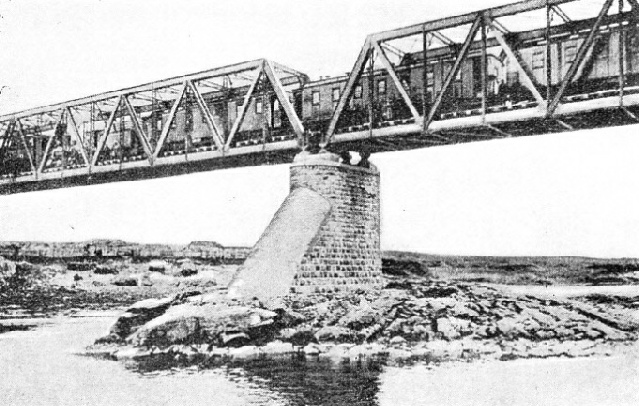

ONE OF THE MANY BRIDGES which are a feature of the Trans-Siberian journey.

The Trans-Siberian line has had an interesting and sometimes stormy history. Long before it came into existence, it was imagined by Jules Verne; but he laid its then imaginary course farther south, through Tartary proper, and called it the “Grand Trans-Asiatic”. Such a line would have been longer, of course, owing to the extra “bulge” of the earth. The line assumed great strategic importance in the early part of this century, during the Russo-Japanese War. It was then a poorly laid affair, and when accidents delayed the traffic on its single track, as they frequently did, confusion became worse confounded on the Russian front. In those days, too, everything had to be ferried across Lake Baikal, causing many delays.

Years before, the Tsar said of it: “The fulfilment of this essential peaceful work, entrusted to me by my beloved father, is my sacred duty and my sincere desire”. In the early days of the line it was anything but an “essential peaceful work”. The line was completed as far as Irkutsk in the winter of 1897-8, and the coming of the twentieth century saw the first through trains running from the Baltic to the Sea of Japan.

The Trans-Siberian Railway, as a matter of fact, was not the only “essential peaceful work” which has had military ambitions mixed up with its inception. Under the former Imperialist regime, more than one Russian general had talked quite openly of the possibilities of invading India which would arise were railway construction pushed far enough in the extreme south of Siberia. Right back in the eighteen-eighties, a strategic line was being quietly driven southwards into the heart of Turkestan, and the Oxus was reached in 1886. No foreigners were allowed to travel on that railway; a number of things were said, and still more were thought, in the high places of the British Government. Several years later, it was the turn of the Russian Government to get uneasy, this time at the Bagdad Railway proposals. The Bagdad Railway would provide a short cut from Western Europe to the Middle East sufficient to head off any attempts at military descent through Russian Turkestan. The Bagdad Railway, too, was being sponsored by Germany, and there was then never any love lost between that country and Russia. When trouble came for Russia, however, it was from Japan, as we know, and a railway invasion of India faded into the background. To-day, though the Indian, Burmese and Malayan railways are still physically isolated from those of both the Near East and the Far East, their north-western terminal in the Khyber Pass is near the rail-head of the Soviet Russian Railways at Termez on the Oxus.

Construction and operation of railway lines in Soviet Turkestan has always been hampered by drifting sand, and returning to the Far East we find that the same thing happens in the great Gobi Desert.

One would not think of the Trans-Siberian Railway, the traffic backbone of the Soviets, as being a link in the communications of the British Empire, but as a matter of fact it provides the sole overland communication between Great Britain and the Crown Colony of Hong-Kong. We have already described how it links up with the South Manchurian and Chinese Government Railways to give access to Peking. From the old capital city, a direct line runs southwards through the heart of China to Canton, whence the Kowloon-Canton Railway, partly owned by British interests, runs directly to the coast opposite the island of Hong-Kong.

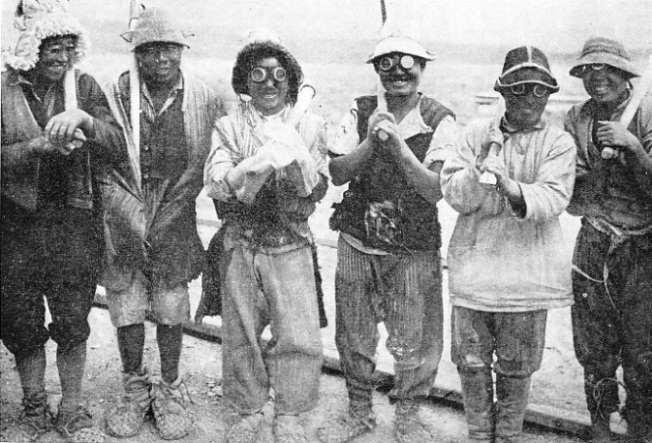

IN THE GOBI DESERT.

A group of gangers who are compelled to wear goggles to protect their eyes against the constant sandstorms which blow across the desert.

You can read more on “Russia and Siberia”, “Russian Steam Locomotives” and “The Trans-Caspian Railway” on this website.

You can read more on the Trans-Siberian Railway in Wonders of World Engineering.