Mammoth locomotives for hauling huge freight trains

LOCOMOTIVES - 58

4000 Class “Big Boy” 4-8-8-4 No. 4003 leaving Cheyenne with a freight train.

TO railroad fans, the initials “UP” have always stood for Union Pacific, but to students of mechanical engineering those same initials recall the phrase “unlimited power”, and there is no better way in which to describe Union Pacific locomotive power practice.

The Union Pacific was part of the first American transcontinental railroad. Particularly in respect of locomotive policy, its progressive management enjoyed a reputation for research, for innovation and for an ability to operate a stud of locomotives representing the ultimate in technical development and capable performance. Thus it was no accident that Union Pacific power was invariably ahead of the company’s current requirements; that freight trains ran on schedules which were highly satisfactory to shippers; and that the combined tonnage and speeds achieved resulted in an operating ratio which even the most exacting accountant termed efficient.

The “Big Boys” were no isolated achievement. The research and development that went into their construction came from a wealth of experience and a long line of remarkable locomotives. By 1930, the railroad had in service almost one hundred 4-12-2s designed, in the words of the then chief of motive power, “to haul mile-long freight trains at passenger train speeds”. That their 4,330hp was capable of pulling at 50 mph the same train that the Mallet compounds they replaced could only struggle with at 25 mph was never in doubt.

The 4-12-2s were unique on four counts. They represented the high watermark in North America in size of locomotive with rigid frames, being the largest non-articulated locomotives ever built. They were the only 12-coupled locomotives constructed in the United States. In an age when built-up crank axles had been superseded by a straight two-cylinder design, the 9000s were given three cylinders. And finally, all but a handful were fitted with the Gresley conjugated valve gear.

The next significant development came in 1936, when the “Challenger” 4-6-6-4 wheel arrangement was introduced. By then the railway had gone right away from the Mallet, or compound articulated, into the realm of simple articulated locomotives. The 3900s were not only remarkable looking engines, they were the first articulated locomotives able to achieve mile-a-minute speeds due to improved front-end boiler support and articulated joints. Indeed, the “Challenger” was a true dual-purpose or mixed-traffic engine and on “second sections” and passenger extras, speeds in the seventies were been recorded.

In parallel with the development of the 4-6-6-4s, the 800s, or Northern 4-8-4s, were introduced. At 456 short tons, they were among the heaviest locomotives of that wheel arrangement. The 4-8-4s looked good on the drawing board and were even better in steel and steam at the head end. Until the advent of the 800s, the older Mountain-class 4-8-2s had reached the limit of tonnage and speed. Double-heading was the rule and UP headquarters in Omaha were looking for something to boost speeds, increase tonnage and cut costs. They certainly found it with the 800s. From the very start in 1937, the first 20 engines in the class averaged 15,000 miles per month per locomotive and pushed up the availability from 65.3 per cent in the case of the Mountains to a remarkable figure of 93.4 per cent.

Costwise, the 800s effected the economy required by management. During the first year of operation, savings of $1¼ million were turned in, being attributed to more-efficient operation, and the elimination of double-heading and extra sections (reliefs). The return on investment achieved was slightly over 50 per cent.

Many of the features of the 800s later came to be employed on the “Big Boys”. The 4-8-4s were the first locomotives on the system to be fitted with roller bearings on all axles and the first to have a boiler of 300lb pressure, which was to play such an important part in the “Big Boy” story. Other new features were the use of a manually controlled blow-off and sludge-removal system, needle-roller bearings for all valve motion parts and mechanical forced-feed lubrication applied widely throughout the locomotive. The 800s were designed for continuous 90 mph operation and early on it was discovered that 3,000 miles could be attained between entering engine terminals for servicing. A typical 1949 diagram of that mileage would be Kansas City-Denver - La Grande — Green River-Ogden - Cheyenne, and in those days it was rare for an 800 to fail to complete its diagram.

Thus was the stage set for the introduction in 1941 of the first of the “Big Boys”, of which 25 were built by Alco at Schenectady, New York, before the end of the war. The huge 4-8-8-4 simple articulated locomotives were the brain-child of the same successful partnership that had directed Union Pacific motive power policy throughout the thirties — Jabelman and Jeffers. The former occupied the position of chief of research and development, motive power and machinery; the latter was chief mechanical engineer.

At the close of the nineteen-thirties, the effects of the depression had ended and American industry was firmly established and expanding fast out on the west coast to escape from the over-populated eastern seaboard. Los Angeles and San Francisco, and indeed the whole of California, were expanding at a rate four-and-a-half times the national average. An ever-increasing freight traffic movement was apparent, linking the population growth in the Pacific with the traditional eastern and mid-western markets. By building heavier and more-powerful freight locomotives, the board of the Union Pacific was determined to increase the railway’s share of the traffic.

Late in 1940, Otto Jabelman decided that not even the 40 “Challengers” would eliminate the older Mallets from double-heading and banking on the Wahsatch and Sherman grades, where the main line crosses the two toughest ranges within the Rockies. By tradition, the American Locomotive Company had built the Union Pacific’s modern power, and Alco was again consulted. This resulted in drawings being prepared under Jabelman’s direction for what were the largest steam locomotives in the world. Such was their size that none ever surpassed them, so the title was retained until the scrapyard cutting torch took its toll.

Previous wheel arrangements all carried distinguishing names—Mountain (4-8-2), Union Pacific (4-12-2), Northern (4-8-4) and Challenger (4-6-6-4), and a similarly stirring name was planned for the 4-8-8-4s. However, history does not relate what it was, because events overtook the decision. The first engine was universally known as “Big Boy”, and the name, originally thought to have been coined by a fitter at the Alco plant, stuck and was officially retained.

The first engine, No 4000, was handed over to the railroad at Council Bluffs on September 4, 1941, and immediately went into freight service between Cheyenne and Ogden hauling tonnage trains over the severe mountain grades. The engine arrived on the Union Pacific not without incident. Schenectady is in the eastern seaboard state of New York and never previously had anything weighing 605 short tons in working order had to be worked the 1,500 miles from there to the Union Pacific. It proved to be a slow and tedious journey.

One of the more delightful, though possibly apocryphal, stories of those early days with No 4000 occurred during a luncheon the Union Pacific board gave to the Chamber of Trade and business community in Omaha to celebrate the arrival of the first “Big Boy”, which was by then in freight service west of Cheyenne. There had always been tremendous rivalry between the railway and its competitor, the Northern Pacific, which had an equal reputation for operating large locomotives and immensely long freight trains. At that date the Northern Pacific had been claiming the largest locomotive, in its Yellowstone 2-8-8-4 Class Z5 engines. The “Big Boys” surpassed the Yellowstones in size and weight, though not in tractive effort or grate area.

Towards the end of the luncheon the Union Pacific president rose to his feet to toast the “Big Boy”, concluding his speech “so I am now proudly able to say that once again the Union Pacific have the largest locomotive on earth”. His words were particularly apt, because at that moment the first “Big Boy” had derailed at a place where there was a “low fill” (or embankment), leaving the divisional master mechanic scratching his head as to precisely how something of that weight should be “put back on”.

The 4000s had a wheelbase of 117 ft 7 in and an overall length of 132 ft 9¼ in, engine and tender. This extreme length necessitated installing 136 ft turntables in the roundhouses at Cheyenne, Green River, Laramie and Ogden, all terminals on the main line to the Pacific coast. At other places the engines were “wyed”, or as we would say, turned on a triangle, while at one or two terminals with only a standard length table the engines were “jack-knifed”. This was a remarkable process in which the engine was run forward over and past the end of the table to enable lifting frogs to be placed behind the tender wheels. The engine was then backed on to the table, with the rear wheels of the tender elevated enough off the end to allow the table to rotate.

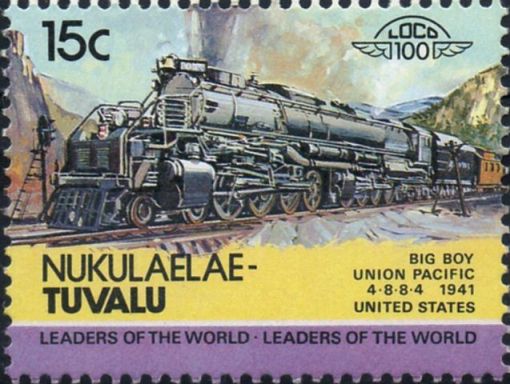

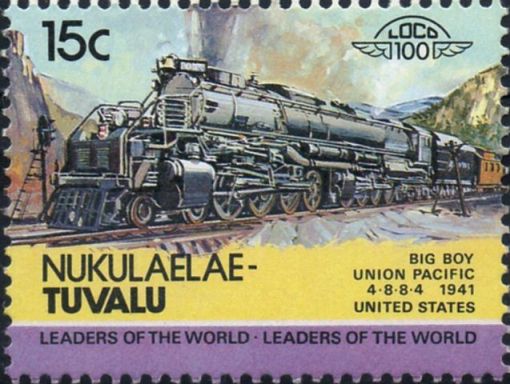

THE “BIG BOY” LOCOMOTIVES featured on a stamp series “Leaders of the World” issued by Tuvalu in 1985.

All 25 “Big Boys” were put into pool service between Cheyenne in the east and Ogden in the west, representing the mountain divisions of the Union Pacific main line. The Union Pacific divides into two distinct parts. At the eastern end the railroad starts at Council Bluffs, Iowa/Omaha, Nebraska (two cities facing one another across the Missouri river) and runs for 528 miles across the rolling prairies of Nebraska to Cheyenne in the extreme south-east corner of Wyoming. In that distance, the track, and indeed the whole terrain, gradually climbs at ten feet each mile uniformly, which averages 1 in 500 for 500 miles without a steep ruling grade. Thus Cheyenne, the capital of Wyoming, is reached at an altitude of 6,060 feet above sea level before the Union Pacific starts mountain railroading. Needless to say, “Big Boys” were never to be found on the Nebraska division, nor indeed east of Cheyenne.

Westward out of Cheyenne, the first 31 miles required westbound trains to be lifted 1,953 feet, to an elevation of 8,013 feet at Sherman summit, on a ruling grade of 1 in 64½ and an average of 1 in 85. The distance over the Wyoming and Utah divisions from Cheyenne to Ogden is somewhat less than so-called level railroading across Nebraska, but it includes the two rugged climbs over Sherman and, west of Green river, through the Wahsatch range with a ruling grade of 1 in 88. The Wahsatch grade was the principal factor in the decision made at an early stage in the design of the 4-8-8-4s that maximum continuous horsepower output should take place at 30 mph.

The “Big Boys” were not often noted in passenger service, although they were designed for speeds of up to 70 mph. During the war they were known on troop trains and in the mid-1940s an occasional passenger extra felt their tremendous force but they were rare birds to be seen heading a “string of varnish”. On freights they excelled.

While most aspects of railroading in North America are large in the widest sense of the word, nonetheless, one was still not quite prepared for the sheer size and bulk of a “Big Boy”. In the United States, mechanical dimensions tend to be given in small units such as pounds and inches— possibly to make the resultant large figures larger still, or more probably because most formulae and calculation require that form—with an impressive result in the case of the 4000s. The locomotive alone weighed 772,000 lb and the total with tender in working order was 1,209,000 lb. The sheet length of 132 ft 9¼ in carried on 16 68 in drivers and two four-wheel trucks (all fitted with roller bearings) gave the effect of a giant centipede from the age of the dinosaurs.

The four cylinders, admittedly not as impressive in size as their low-pressure counterparts on a true Mallet, but still eye-catching at 23¾ in bore and a 32 in stroke, were fed by a boiler pressed for 300 lb to give a tractive effort of 135,375 lb. Perhaps the most awe-inspiring statistic was to discover that the two sand boxes astride the boiler had a total capacity of three tons.

The 14-wheel centipede-type tender was no less impressive. The centipede was a development of the cylindrical Vanderbilt tank and was designed to overcome the 60,000 lb axle weight restriction by using 10 rigid wheels preceded by a four-wheel truck (known as a 4-10-0 tender arrangement). The 42 in wheels were all mounted on roller bearings. Capacities varied slightly on the different marks of centipede tank, but the final arrangement for the tenders running behind Nos 4020-24 took 25,000 US gallons of water and 28 short tons of coal. Additional baffle plates were fitted after early experience of surging, particularly when the water was down to half capacity or less. Cheyenne yard and terminal used to abound in stories of head-end brakesmen and firemen arriving back off Sherman hill ashen-faced from what became known as “centipede sickness”. In common with American practice, the tender contained a worm-wheel stoker.

At one stage in design of the locomotive, boosters were considered, but they were not used. The boiler varied in diameter between 95 in and 105 in, with a welded firebox 235 in by 96½ in, and a combustion chamber 112 in in length. It is wonderful what can be done with a loading gauge of 15 ft 6 in height and 10 ft 9 in width and an axle load of 30 short tons running on 133 lb rail! In accordance with normal Union Pacific practice at that date, a live-steam injector was fitted on one side and an exhaust steam and centrifugal pumps on the other. The locomotive was given a double chimney consisting of four-jet exhaust nozzles on a common base.

Experiments in oil-firing were carried out on No 4005 during 1947-48, but the single burner could not get the fire close enough to the crown to generate the required heat. The resultant poor oil combustion necessitated reconversion back to coal in March 1948.

The two engine beds on the 4-8-8-4s were connected by means of a vertical articulated hinge, so arranged that when the boiler was full, a seven-ton load was applied to the tongue of the rear bed unit; consequently, the two engine beds were held rigid in the vertical plane, unlike what had been experienced with their predecessors. A new type of articulated side rod was fitted to eliminate the more-usual knuckle-pin connections. Each set of cylinders and frame was produced in an integral mono-block casting. The live and exhaust steam pipes were larger than anything previously used to permit better utilisation of boiler capacity and obtain maximum power output.

One of the more novel—for 1941 — innovations was the running gear arrangement, in which a system of lateral motion control was designed to fit all wheels to the rails, thus to reduce binding on curvature to a minimum. In addition, it adjusted the wheels to vertical track differential with minimum disturbance to the weight distribution of the locomotive. The effect was to produce a stable engine on straight track but with the ability to adjust to curvature. Consequently the “Big Boys” used to “heel to the curves” smoothly without the tell-tale violent front-end oscillation or nosing so characteristic of articulated locos. From the cab, the impression on curves was totally different from riding on articulated engines of other railroads. On the latter in a curve, you could be left with the feeling of the front drivers answering to the curvature while the boiler (rigid to the rear drivers) continued straight on for what seemed an age before suddenly jerking round when the rear drivers hit the curve.

The punishment to which the “Big Boys” were subjected is beyond anything known in this country, so that a word or two on their performance will not be out of place. One hot July day in 1949, westbound extra freight consisting of ninety-nine loads and seven empties plus caboose (107 cars weighing 5,192 tons) was awaiting the “high ball” to leave Cheyenne yard behind 4-8-8-4 No. 4023, with 4-6-6-4 No. 3819 as pilot. One moment the two giants were quietly simmering in the heat, and the next, a roar like thunder as the engineers opened their throttles and prepared to surmount the 1 in 81 grade immediately they emerged on to the main line.

Engineer Hooker of the “Big Boy” started by using 65 per cent cut-off and full throttle, but after four miles, in which speed had reached 19 mph, there came the ruling grade of 1 in 64½; even though the cut-off was altered to 75 per cent, speed gradually dropped in five miles to 8 mph. Another two miles and speed had increased by one mile per hour, but only at the expense of the boiler pressure which had declined (small wonder with full throttle and 75 per cent cut-off) from 295 to 260 lb; so, the Elesco pump was temporarily shut off until the pressure increased. By that time all normal sounds were eliminated by the pounding and slipping of 28 driving-wheels; the sun was entirely blotted out by the combined efforts of both exhausts and a black mass resembling a thunder cloud drifted in the otherwise clear atmosphere right the way back to Cheyenne.

Otto water-tower hove into sight and when we stopped with our pilot spotted opposite the column we were 69¾ minutes and 14 miles out of Cheyenne. To save restarting the train twice, the second engine is watered by cutting the locomotives off the train and running them forward. But to start the train once, let alone twice, required considerable ingenuity, as it is impossible for a train of that tonnage to be restarted on a 1 in 64½ grade by only two locomotives. The regular procedure is that a freight train stopped at the water tower is banked by the pilot engine of the following freighter, the pusher dropping off when it comes up to the water-column—thus each train has rear-end assistance for restarting. Freight trains are sent “over the top” in batches of about four or five during lulls in the passenger service; the fifth or last train is lightly loaded so that it can get away from Otto without rear-end assistance.

The “extra freight west” restarted 12½ minutes after arriving there and achieved 14 mph in six minutes nine seconds, when the 4-6-6-4 pusher dropped off. Speed thereupon began to diminish and was down to 5 mph when the grade changed for the better to 1 in 81. No 4023 might have been given some respite there, but still Hooker kept his engine at full throttle arid in full forward gear. Back to 5 mph for some more ruling grade, but on the final six miles of lighter grades, the train hit 16 mph for the first time in two hours eleven minutes, and when the train stopped at Sherman to detach the pilot, the 31 miles had taken 162¼ minutes running time. Throughout, the “Big Boy” had been worked at full throttle and never less than 65 per cent cut-off, spending 109 minutes in full forward gear! It had used about 23 tons of coal and 26,000 gallons of water in 31 miles, all in order to lift 5,000 tons a vertical height of 2,000 feet.

The description of that particular run has been included to illustrate the way in which the 4000s could be operated under arduous conditions. It is not typical of Sherman in that the pilot, No 3819, was not steaming well and therefore contributing less than would normally have been expected.

The “Big Boys” truly lived up to their name and reputation. Perhaps the most memorable sight of all was the view forward from the cab of a 4-8-8-4 piloted by a 4-6-6-4. The tender of the pilot engine seemed far enough away, but the whole combination appeared to stretch far into the distance.

THE “BIG BOY” IS A GIANT 4-8-8-4 Mallet type locomotive. It is hinged in the centre to allow it to negotiate curves. One “Big Boy” does the work of two engines and set a new world standard for size and power.

You can read more on “Articulated Locomotives”, “Giant American Locomotives”, “Locomotive Giants” and “The Union Pacific Streamlined Express” on this website.