The automatic stoker, though not strictly a fuel-economizing device, is a cleaner and easier method of feeding the fire

DESIGN AND INVENTION - 18

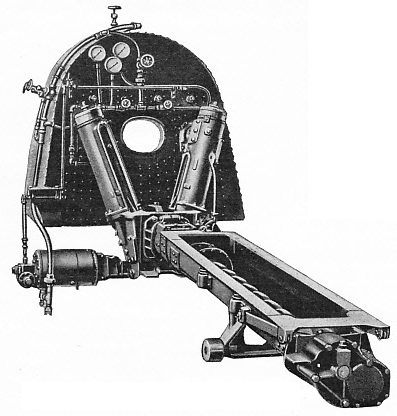

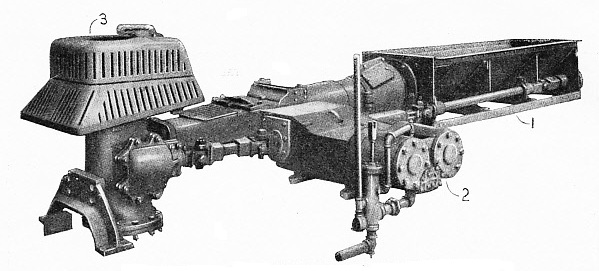

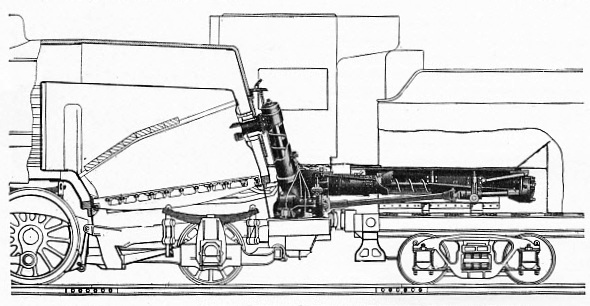

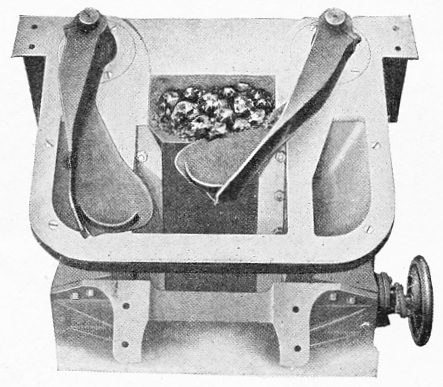

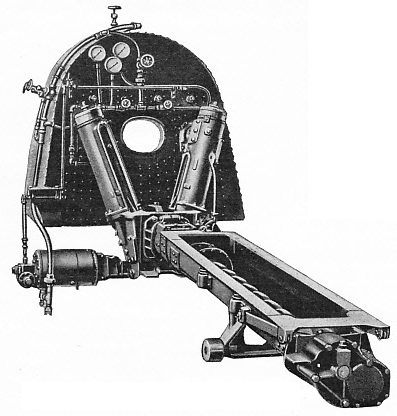

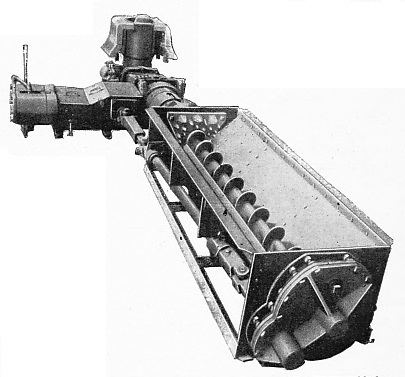

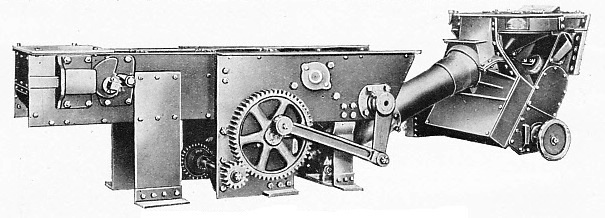

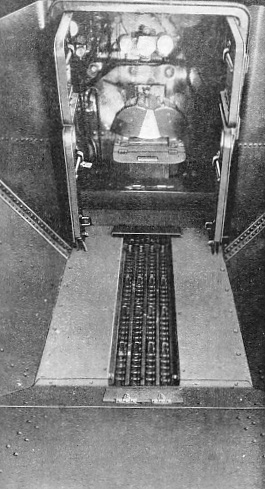

GENERAL VIEW OF THE DU PONT-SIMPLEX MECHANICAL STOKER. 1. Feeder trough for tender. 2. Stoker driving-engine. 3. Distributor and protective grate from which broken coal is blown into the fire-box by steam-jets.

AMONG the many locomotive developments, which have been advanced to a high standard of reliability, must be mentioned the mechanical method of feeding the hungry furnace with a steady and continuous stream of coal in order to maintain the desired head of steam under fluctuating conditions. In those countries where fuel-oil is readily and cheaply forthcoming, mechanical firing has attained a high stage of perfection, but automatic stoking with a liquid differs vastly from that of delivering a solid fuel into the fire-box. The former operation is as simple as can be conceived; control merely demands the manipulation of a valve or two.

All railways are not in the position to use oil-fuel. The factor of cost decisively intervenes. Yet those systems which stake their steam-raising efforts upon coal were confronted with the necessity to reduce the cost of coping with their traffic. This could only be done by greatly increasing the weight of the train haul, which, in turn, demanded the employment of more powerful engines.

The locomotive builders responded, but in remedying one evil they created another. They increased the dimensions of the boiler, and also those of the fire-box, to such an extent that it became physically impossible for one man to keep the furnace adequately supplied. Thereupon the ingenious of mind attacked the issue of reducing the solid coal to the comparative level of the liquid fuel in so far as charging the furnace is concerned, and it was not long before the first mechanical stoker made its appearance. True, it was primitive, but it carried the germ of the idea, and that sufficed to attract a number of other brilliant minds to the study of the one and most vital issue in the railway world at that time.

Under concentrated study and experiment evolution was rapid. In the course of two or three years there was a multiplicity of appliances for mechanically firing the locomotive. This activity was enthusiastically stimulated by the railways, and facilities for subjecting the various conceptions to trial were readily granted, but the great majority have been found wanting. The result is that, to-day, there are not more than half a dozen types which have passed to the stage of application.

Under concentrated study and experiment evolution was rapid. In the course of two or three years there was a multiplicity of appliances for mechanically firing the locomotive. This activity was enthusiastically stimulated by the railways, and facilities for subjecting the various conceptions to trial were readily granted, but the great majority have been found wanting. The result is that, to-day, there are not more than half a dozen types which have passed to the stage of application.

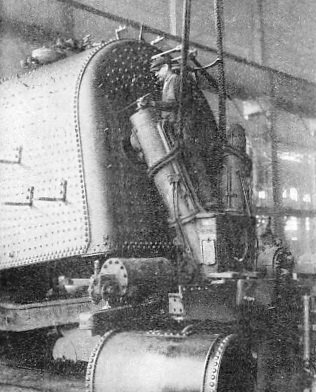

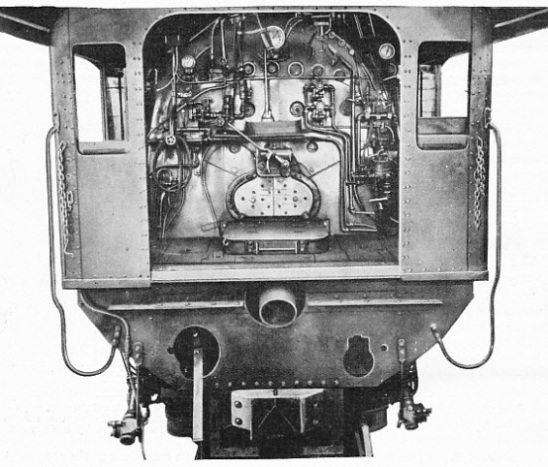

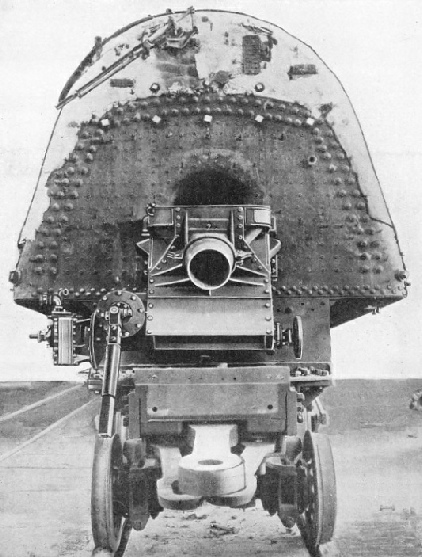

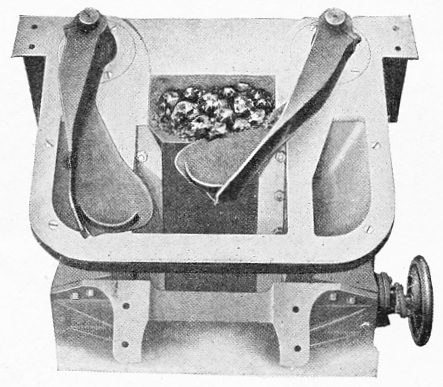

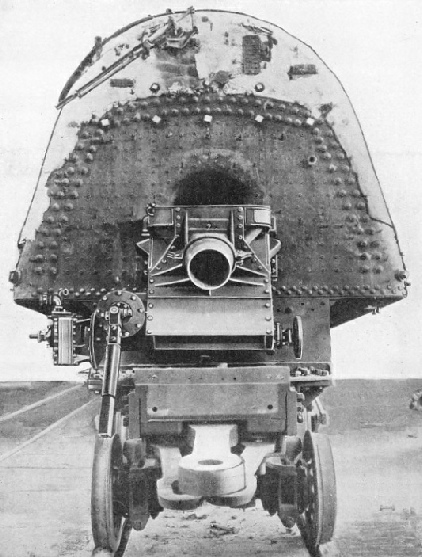

REAR VIEW OF DU PONT-SIMPLEX MECHANICAL STOKER.

Shows the tender trough, crusher plate, part of horizontal conveying system and the method of driving.

The task is invested with many interesting and intricate problems, but there are three of cardinal significance; if they cannot be solved the conception is doomed to failure. In the first place, it is obvious that to bring the dense solid fuel to the comparative mobile level of a liquid it must be reduced to a fine form - be pulverized. This demands power, while the crushed fuel must be fed forward in a steady stream, which imposes a drive. Now there is very little space in the cab of a locomotive to receive any additional power unit, especially when the conditions of accessibility for inspection and repairs must be respected.

Secondly, as the crushing component of the machine must necessarily be contiguous to the coal supply carried in the tender, while the furnace-feeding section must be mounted on the engine, there must be a flexible connexion between the two integral parts. Thirdly - and this is the most critical and perplexing condition to meet - the draught and its distribution over the grate area are continually changing in intensity, in accordance with the variations in the cut-off, and the possible improper adjustment or derangement of the draught regulating appliances in the front end, or smoke-box of the locomotive.

The fire-box varies widely in shape, according to the type of locomotive, and so does the corresponding grate area. Then the rate of combustion is not the same over the whole of the grate surface; the distribution of the incoming coal has to be varied considerably in accordance with the condition of the fire, so that the thin level layer of incandescent fuel which the driver appreciates, and ensures economical combustion, and, incidentally, the minimum consumption of coal for the work performed, may be maintained. Under skilled manual stoking the maintenance of the desired fire conditions is effectively secured.

The railways promptly turned to the automatic stoker when it had established a sufficient degree of utility, and locomotives equipped therewith made their appearance upon the various American railways. But to general surprise the results were markedly disappointing. Forthwith, an elaborate investigation was instituted. Scientific tests conducted at the University of Illinois proved highly illuminating and yet disturbing. A considerable proportion of the fuel delivered into the fire-box was discovered either to escape or to undergo only partial combustion. It was ejected through the smoke-stack, and this loss was found to amount to as much as 17 per cent, at high rates of combustion, of the fuel fired. In other words, nearly one-fifth of the coal failed to contribute to the raising of steam.

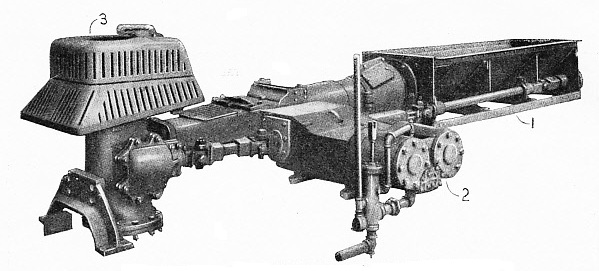

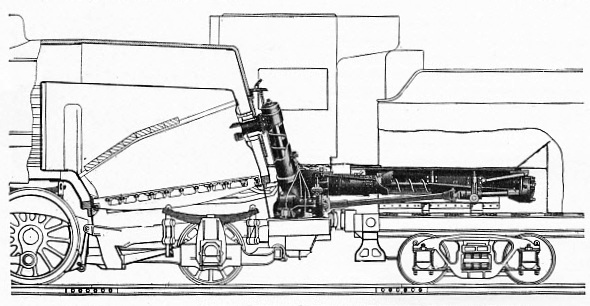

SCHEMATIC DIAGRAM SHOWING FIXING OF DUPLEX STOKER TO THE LOCOMOTIVE.

The conveying and elevating screws, and the tube opening at the top of the elevator, through which the crushed coal is blown into the fire-box by steam are shown.

This discovery led to further diligent investigation of the effectiveness of the stokers in use, and results were found to be corroborative. The earlier types of machines were discovered to be the worst offenders; some of them wasted as much as 40 per cent of the fuel fed to the furnace, while the losses through the smoke-stack in the form of cinders varied with the degree of fineness to which the coal was reduced.

The reason was ascertained. The fine particles, being relatively light and introduced into the fire-box in the form of a powder-spray, were caught up by the stream of gases of combustion, which move at high velocity, and so were impelled with great speed through the tubes, to be thrown into the air either as cinders or live sparks. It was found that even relatively large pieces of coal, considered upon the pulverized basis, were susceptible to this action. From this it was obvious that the losses through the smoke-stack were proportionate to the degree of fineness to which the coal was reduced by the crushing element of the machine, though it was appreciably influenced by another important factor - the height at which the fuel was delivered into the fire-box.

The majority of the machines fed the coal at the approximate level of the arch within the box, and so met the stream of gases near the point where they were swirling round the deflexion, to be swept over the top of the arch into the tubes. From the observations made, the investigators came to the further conclusion that the manner in, and the height at, which the coal was introduced into the fire-box, had the same relationship to losses through the smokestack as the degree of fineness to which the coal was crushed.

As the result of these searching inquiries the development of an “underfeed” type of automatic stoker was advocated. Now the majority submitted for trial were of the “overfeed” design - that is to say, they discharged the coal-dust stream at an appreciable height into the fire-box. The former principle had previously been submitted to experiment, only to be abandoned because of the restrictions in grate area and other influences, which, at the time, were considered to be insuperable. Nevertheless, the scientific report upon the whole subject prompted a reconcentration of thought upon the scientific recommendation, and although the underfeed suggestion has not been fully adopted, owing to the general limitations imposed by the peculiar construction of the locomotive, it has been brought as close to that ideal as at present is possible.

To-day the automatic stoker fully harmonizes with the high standard of excellence to which the locomotive and its more familiar details have been advanced. The basic principle of distributing the powdered coal over the grate area is either by means of a steam-jet, or by mechanically-moving arms, described as shovels.

The du Pont-Simplex Stoker

The first-named method is incorporated in the du Pont-Simplex Stoker, one of the oldest mechanical methods of firing the locomotive. Upon the realization of the significance of stack losses the apparatus was completely remodelled. In its redesigned form this stoker has been transformed into an economical and efficient machine. It is of simple design, and has the fewest possible number of working parts.

This stoker comprises two main elements - the device for receiving the coal from the tender, crushing it, and leading the pulverized fuel forward, and the fire-box distributor, respectively. Below the tender deck is a trough which receives the coal by gravity; the flow is partially regulated by sliding plates. Inside this trough is a horizontal shaft, with a continuous spiral blade forming a screw conveyer; the latter is so placed in the former, and the whole so housed, as to minimize the possibility of foreign substances falling into the trough and working under the screw, thus causing it to jam and stop.

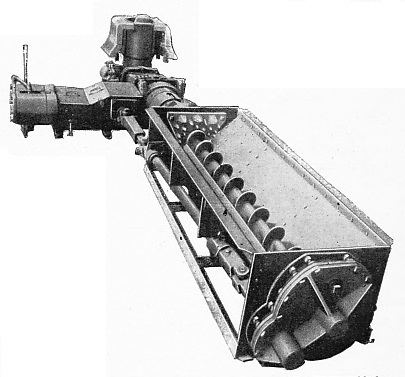

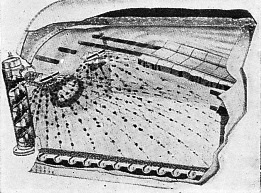

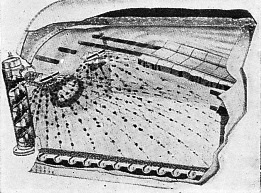

DIAGRAMMATIC VIEW OF FIRE-BOX WITH DUPLEX STOKER. This shows the manner in which coal is spread over the grate area, and the method of lifting the crushed coal from the hopper into the distributor tube.

At the forward end of the trough is a plate carrying a number of inwardly projecting spikes. The coal, dropping into the trough and advanced through the latter by the action of the helicoidal screw, forces the lumps against this crusher plate, and under the pressure exerted the masses are split into small pieces. This crushing action is continued until the coal has been reduced to sufficiently small size - without actually being ground to dust - for falling into the conveyer which moves it to the fire-box.

The main conveyer-trough, with its screw, is continued forward in a second section under the foot-plate and mud-ring of the boiler to a point in the rear end of the ash-pan. Naturally, as the engine and tender are flexibly connected, the conveyer and housing extension from tender to engine must conform to these conditions. This is accomplished by providing the intermediate section with universal and ball joints at each end, with a central sliding joint in the centre. This permits the stoker to adapt itself to the sharpest curve traversed by the locomotive, and, through the sliding joint, enables the two sections to come adrift instantly.

The slip-joint is not only provided in the housing, but in the screw-conveyer, within, as well. Consequently, should the locomotive be derailed, or the draw-bars break by accident, or be released to permit the tender to be pulled back for inspection of the draft gear, the conveyer comes instantly apart, and may be slipped together as readily when the tender is replaced. As this central section is completely housed no loss of fuel in its passage from the tender to distributor box can take place.

At the forward end is the distributor. This comprises a vertical cylindrical housing carrying a vertical lifting screw. The coal thus raised overflows, or spills, on to the protecting grate, or, as it is called, the firing-table - a flat cast-iron surface, whence it is blown into the furnace, where required, by the steam-jets. From its action this device is known as the distributor. It is a heavy casting, set above the firing-table, and pierced with sixteen holes, drilled in several groups. Each group is controlled by a separate valve. Consequently the shape of the fire-box or the distribution of the draught is immaterial; the even spreading of the fuel over the grate area is secured by merely adjusting the pressure on each set of jets through the control valves.

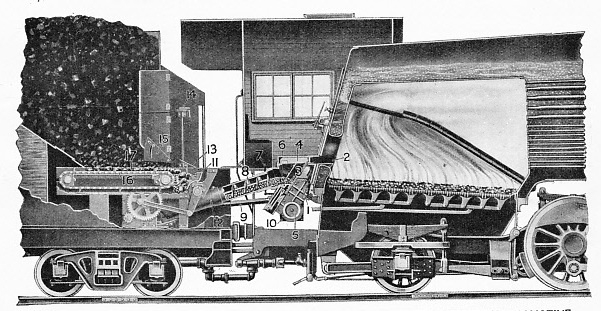

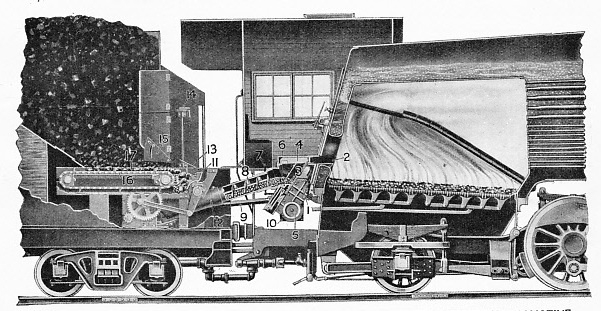

SCHEMATIC DIAGRAM OF ELVIN MECHANICAL STOKER SET IN POSITION ON THE LOCOMOTIVE.

1. Stoker. 2. Deflexion plate. 3. Elevator. 4. Shovel for throwing coal into the fire-box. 5. Hand-wheel. 6. Mechanical shovel-box. 7. Reverse lever. 8. Conveyer for bringing crushed coal forward. 9. Shaft through which drive is transmitted to tender component. 10. Stoker engine. 11. Crusher. 12. Conveyer hopper. 13. Crusher cover. 14. Coal-feed regulator. 15. Coal gate. 16. Feeder chains. 17. Feeder trough.

The vertical housing above the grate level is surrounded by a protecting grate set a few inches away. Its purpose is to safeguard the first-named against overheating. It is pierced with vertical slots through which air from the ash-pan is pulled by the draught suction to aid combustion and also to assist in preserving the protecting grate from becoming overheated. The pipes supplying the steam to the distributor are protected from the heat of the fire by being mounted behind the vertical housing and inside the protecting grate, though the distributing jet itself is purposely exposed to the heat of the fire to superheat the steam.

The operation of the stoker is carried out by means of an independent motive unit. This is a slow-speed two-cylinder horizontal engine, of simple construction, carried on the forward part of the apparatus. It has to drive the conveyer-screw to give continuous forward feeding of the coal; that for the helicoidal screw in the tender trough is through enclosed spur gears at the rear end of the latter; while that for the forward elevating screw is through a train of bevel gears. The section of the driving shaft between the locomotive and the tender is similarly provided with a slip-joint, to take care of the displacement when rounding curves, which likewise drops apart when the tender is separated from the engine.

The volume of coal fed to the fire-box is regulated by the height of the coal-crushing plate above the screw in the conveyer-trough, and the speed of the stoker engine. The first-named is so set that any foreign substance, associated with the coal which cannot be crushed, is prevented from passing into the other parts of the mechanism. Should the apparatus be brought to a stop through jamming, it is only necessary to examine the conveyer-trough to discover the cause of the mishap. Anything which is able to pass the crusher plate must be carried right through to the fire-box; it cannot foul the apparatus at any intermediate point, because the crusher opening acts as “the neck of the bottle”.

In determining the height for the delivery of the pulverized coal into the fire-box advantage was taken of the lessons taught by practical application on the road, and in stationary testing-plants. To counteract the lifting action of the draught in the firebox the steam-jet blowing the powdered coal is so set that downward drive is assured towards the bed of the fire. Consequently, practically none of the fuel is carried above the arch to be swept through the flues by the rapidly moving gases of combustion and finally belched into the air in the form of sparks or cinders.

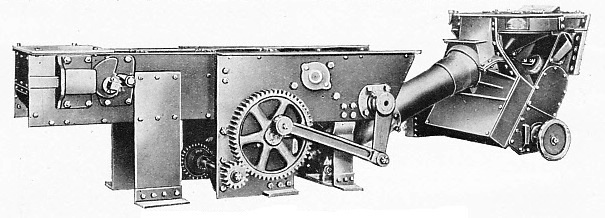

SIDE VIEW OF COMPLETE ELVIN AUTOMATIC STOKER. On the left, the element carried upon the tender of the locomotive with its drive; on the right, the section fitted to the boiler back-head with interconnecting inclined conveyer through which the

crushed coal is moved forward.

It must not be thought that the automatic stoker completely displaces manual labour in firing the engine. It is preferable that the fire should be started and maintained by hand in the usual manner until the locomotive has been coupled up and the train has started on its journey. Once the stoker has been set in operation, and the jets adjusted, no further variation is required, although, after starting, the fire should be examined occasionally to see how it is burning, and the control varied accordingly.

The flow of the coal and speed of the conveyer can be ascertained by peering through the grating in the forward housing. Should the rotation of the screw be momentarily arrested the fact is revealed by a rise in the pressure of the steam-gauge, but its fall to normal, and oscillation between the 15- and 25-lb scale calibrations, indicates resumption of operation. At times an abnormal obstruction is apt to be recorded — a piece of iron or some other equally resistant foreign material associated with the coal drops into the trough to jam against the crusher plate and stop the rotation of the screw. In this event the stoker engine will be pulled up, necessitating the removal of the obstacle by hand.

The Elvin Automatic Stoker

The mechanical shovel method of distributing the coal into the fire-box constitutes the outstanding characteristic of the Elvin automatic stoker, although the machine has many other distinguishing features. This contribution to the great locomotive firing problem was conceived by Mr. A. G. Elvin, in 1910, but constant development has enabled many improvements towards higher efficiency to be attained.

This apparatus similarly comprises two fundamental elements - the coal-breaking component on the tender, and the stoking unit on the engine, respectively, with an interconnecting feeder. The coal-breaker is fitted to the bottom of the tender, and combined with the feeder. The latter is composed of four endless drag chains, travelling round sprockets at either end of a wide shallow trough. These move forward intermittently; the travelling speed is varied at the will of the fireman in order to give the desired delivery into the fire-box. This ranges up to a maximum of about 14,000 lb per hour, with complete control over the coal at all rates of discharge.

SHOVEL-BOX OF THE ELVIN AUTOMATIC STOKER

This sectional view shows the alternately oscillating mechanical shovels, and how coal raised through the elevator to the table is swept forward into the fire by each stroke.

It is not necessary to pass all coal through the crushing process. An appreciable quantity has already been reduced to the desired size in the handling between the mine and the locomotive tender. This is permitted to drop through suitable slots into the hopper beneath before the crusher is reached. Owing to the feeder having only an intermittent movement, and one which does not exceed a maximum of 1½ inches per impulse - six feet per minute - there is no possibility of these slots becoming fouled.

The breaker is of the reciprocating type which has been used for years for a similar purpose in a variety of industries, and so is a well-tried reliable device. The only outstanding difference is that it has not a completely revolving crusher roll. It is fitted with a cover-plate which, when latched at an angle over the crusher, forms a guard, and when dropped flat forms a shovel-plate for hand-shovelling, while the locomotive is resting.

A short distance beyond the crusher are the coal-gates; through these the pulverized fuel drops into the hopper with the fine coal which has previously been deposited in this receptacle, whence it is carried to the stoker. One feature of the tender element is that the coal-breaker is outside the coal bunker, and is therefore constantly within full view of the fireman. Should a foreign obstacle, associated with the coal and resistant to crushing, be carried forward to the breaker, it will become fixed at this point and stop the machine. A slight reverse of the stoker in order to release the jaws of the breaker suffices to free the obstacle for removal.

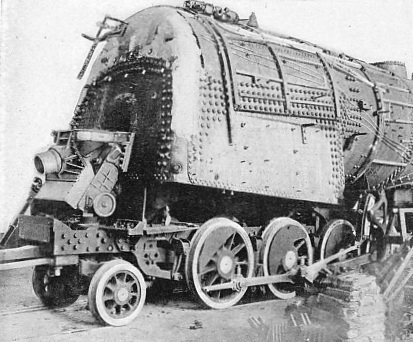

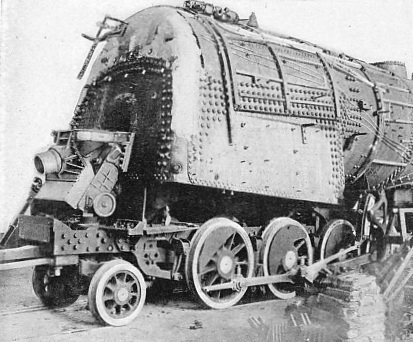

The pulverized coal, collecting in the hopper beneath the cylindrical feeder trough, is led to the stoker unit through an inclined screw-conveyer, which delivers the coal to the rectangular elevator of the stoker to be raised directly to the firing shovels. The fitting of the stoker to its designed position is shown in the illustration on this page showing one of the large Mallet articulated locomotives, built for the Pekin-Suiyan Railway in China. A suitable filler block is studded to the boiler back-head on which the stoker is mounted, by means of eight bolts, two brackets fastened to the mud-ring serving to brace it on the lower side. Thus the stoker is set wholly clear of the locomotive frame.

The shovels (small arms with a scoop) are mounted on either side of the opening through which the coal is delivered by the stoker elevator. They sweep to and fro alternately, as it were, across the table towards the fire, so that any coal raised to the table, irrespective of its quantity, must be swept into the fire. Furthermore, the shovels have accelerated and retarded motions imparted to them mechanically, such as will ensure the correct distribution of the fuel.

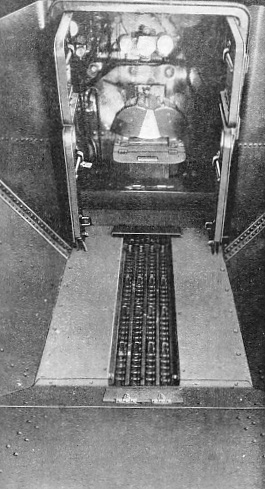

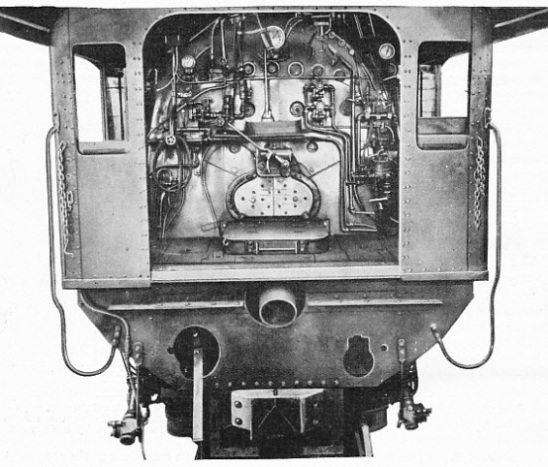

LOCOMOTIVE CAB SHOWING ELVIN STOKER IN POSITION.

The fire-box section projects only slightly above the floor, and so preserves the roominess of the cab.

This distinctive shovel movement is accomplished by means of a very simple and substantial action. Approximately in the centre of the stoker-casing is a fixed shaft, on which is mounted, on ball-bearings, a rotating cam, having two grooves, one front and one back. On either side of, and above, this cam, is an arm, the lower end of which engages in the cam groove, the one at the front, and the other at the back, respectively. As this cam revolves it causes the two arms to oscillate on their individual pivot-shafts, and thus gives the motion, dictated by the cam grooves. As half of the cam groove is circular one arm and its shovel are at rest while the fellow arm and shovel are working. The cam itself is driven by a worm-gear mounted on the main shaft.

The stoker is driven by a simple, compact and efficient engine. This is of novel design with a double reciprocating square piston. It has no dead centre, and can be started, stopped or reversed instantly by a convenient throttle and reverse lever. There are no eccentrics, or piston-ring, bolt or nut inside the casing. It demands little space, and is capable of standing up to long arduous work. The engine casing is bolted to the stoker-frame, and the crank is mounted directly on the end of the stoker-drive shaft, so that the power is applied without the intermediary of chains or gears. The engine is rated at 6 horse-power with 100 lb pressure of steam, but as in use the steam pressure averages only about 25 lb, considerably less than 2 horse-power is required to actuate the whole mechanism.

The engine is completed with a governor to compensate for the fluctuating load on the stoker engine, arising from the varying strain imposed upon the coal crusher, according to the character of the fuel in use. This is also of novel design. It has been introduced to maintain a uniform working speed on the stoking shovels, and its most notable feature is a variable speed-control.

ELVIN MECHANICAL STOKER FITTED TO A “MALLET” LOCOMOTIVE

This engine furnishes the power for operating the drag chain, feeder, and coal crusher on the tender, the screw-conveyer bringing the coal forward, and the stoker elevator by which the coal is raised to the shovel table, and also the alternately oscillating shovels. The elevator mechanism, driven through gear and pinion, ensures that the elevator rises twice for each revolution of the cam actuating the two shovels, so that each shovel may be served in turn.

The coal is distributed in the fire-box rapidly and evenly in such a manner that a uniformly thin lire is maintained over the grate area, except at the sides and ends of the fire-box where the lire is slightly heavier. The action of the shovels, and the placing of the fuel, are independent of the amount of coal being used, as this factor is dependent upon the quantity fed from the tender. When the stoker is working to full capacity the inclined screw-conveyer is only about half-full.

The volume of coal delivered to each shovel can be varied from a few ounces to about 7 lb, and is thrown into the furnace at the rate of 36 to 40 shovels per minute. Delivery of the coal in correctly adjusted and distributed charges is most favourable to economical consumption. At the same time it gives a lire which throws off little smoke, and reduces the losses through the smoke-stack to a pronounced degree. This avoidance of waste in sparks and cinders is also influenced materially by the setting of the firing position; in this case the shovels are placed about 14 inches above the grate.

In designing the stoker the question of weight has received full consideration in order that the load imposed upon the trailing wheels may not be rendered excessive. The total weight of the firing element, including its engine, fitted to the Chinese “Mallet” already mentioned, is less than 3,000 lb. Suitable provision is also made for the displacement between locomotive and tender when travelling round curves, as well as for ready disconnexion when the tender is drawn back for inspection of the draught gear. The greater part of the machine is carried below the foot-plate; consequently there is very little encroachment upon the confined space within the cab.

FEEDER TROUGH OF ELVIN MECHANICAL STOKER FITTED TO LOCOMOTIVE TENDER

The coal is moved forward over the four travelling chains to the front end of the trough against the coal-breaker, and after being crushed falls into the hopper below for movement to the firebox.

The operation of this mechanical stoker is solely dependent, after it has once been set in motion, upon the manipulation of the speed-regulating valve in the cab. This, after once being set, is not touched until a change in speed is desired. Starting and stopping the machine, however, is accomplished by means of the main valve.

The task imposed upon the fireman, in so far as stoking is concerned, is as simple as could be contrived; he is not called upon to leave his seat unless something unexpected supervenes. He need not move to ascertain how much coal is being fired, since he has only to turn his head to observe the quantity being brought forward with each movement of the feeder chain. There is no necessity to open the door to look into the fire-box in order to satisfy himself on this point. A brief experience enables him to determine the quantity of coal required for the different conditions of load and grade upon the road.

In the same way he will speedily master the speed at which the stoker should be run in order to gain the most satisfactory results. This factor is dependent upon the size of the fire-box and the working of the locomotive, but from 15 to 20 swings of each shovel - 30 to 40 for the complete stoker - per minute, will be found productive of the highest efficiency. If the stoker be run too fast it will throw the coal too far forward; while, on the other hand, if it be run at too slow a speed it will starve the front end of the fire through discharging the fuel too far to the rear.

The steam method of distributing the pulverized fuel in the fire-box is embraced in the “Duplex” apparatus; the first of these was installed in 1911, but more than 5,000 locomotives, in operation throughout the world, are fitted with it to-day. This appliance comprises four essential elements - the crusher with conveyer from the tender, the elevator to the fire-box, the distributor, and the driving engine, respectively.

The tender component consists of a heavy wrought steel trough, fitted with a helicoidal screw, which moves the coal, falling into the trough, forwards, into the crushing zone with its crushing plate, where the lumps are reduced to the desired size. This unit does not belong to the tender but to the engine, so that when the connecting gear is released, to allow the tender to be drawn back, the latter comes clear of the stoker-conveyer which merely rests in angle-bearings in the tender.

The tender component consists of a heavy wrought steel trough, fitted with a helicoidal screw, which moves the coal, falling into the trough, forwards, into the crushing zone with its crushing plate, where the lumps are reduced to the desired size. This unit does not belong to the tender but to the engine, so that when the connecting gear is released, to allow the tender to be drawn back, the latter comes clear of the stoker-conveyer which merely rests in angle-bearings in the tender.

FIRE-BOX UNIT OF THE ELVIN MECHANICAL STOKER IN POSITION. End view, showing method of mounting to boiler back-head. To permit instant withdrawal of the tender for examination of the draught gear, the driving shaft of the engine has a square end which engages with a sleeve on the tender unit, while the spiral conveyer slips over the mouth of the stoker.

The coal is fed forward to a transfer hopper, having a dividing rib, flexibly connected to the conveyer by a ball-and-socket joint. From the transfer hopper rise two vertical cylinders, set like a V; the upper ends of these terminate in elbow tubes set in the back-head of the locomotive, on either side of the fire-box door. Each vertical cylinder carries a helicoidal screw, termed the elevator, and the purpose of the transfer hopper is to feed these two lifting units with the desired quantities of the broken fuel.

Upon reaching the top of each elevator the coal drops into the elbow, which is really the distributor, because thence the fuel is blown into the fire-box. A low-pressure steam-jet performs this function. It is set in the bottom portion and at the back of each distributor tube elbow. Thus two streams of coal are delivered into the fire-box, one from each side of the door of the latter. The lower layers of coal ejected from the distributors strike a deflecting rib on the front of each component, and so become thrown towards the rear portion of the grate; while the upper layers are discharged over the forward portion. The introduction of the deflecting ribs not only ensures that the entire grate will be covered, but also minimizes the losses of partially consumed coal through the smoke-stack.

Distribution of the coal is varied by adjustment of the steam-pressure at the jets, as well as by the movement of the dividing rib in the transfer hopper. If desired, the fireman can shut down one elevator and distributor entirely; or he may vary the quantity of coal ejected merely by changing the position of the dividing rib in the transfer hopper, since this rib controls the quantity of fuel fed to each elevator. The dividing rib is moved by means of a lever. Owing to the perfection of control a level light fire car be carried, and perfect combustion ensured.

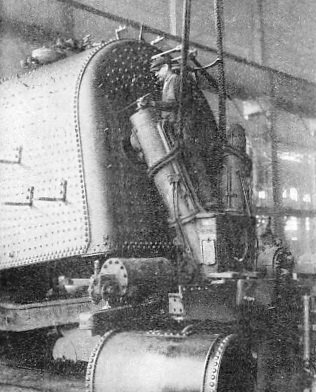

ATTACHMENT OF DUPLEX STOKER TO BACK-HEAD OF LOCOMOTIVE. Showing trough with helicoidal screw fixed under tender by which coal is carried forward against crusher plate; also two vertically inclined elevators which lift the coal to the fire-box door. At left, simple single-cylinder engine which drives the apparatus.

The stoker is driven by a single-cylinder steam-engine; this cylinder measures 11 by 17¾ inches, and the head is similar to the top casing of the Westinghouse air-pump. It is attached to the transfer hopper beneath the foot-plate, and a driving rack transmits the power to the conveyer-screw and elevators the quantity of coal fed forward from the tender is governed by the speed of this engine.

The Duplex Stoker will handle all varieties of coal, from the hardest of lump to wet slack, with equal facility. It occupies but little room in the cab; the impingement upon the space in which is confined to the two elevator casings projecting a short distance above the deck, and close to the back-head, so that there is no obstruction. It is also practically noiseless owing to the slow movement, method of elevating, and the system of distributing the fuel. The driving engine may be started, stopped, or reversed by a single lever, while the conveying screws can be similarly handled, individually or in combination.

According to the experience which has been accumulated any locomotive performing passenger or freight duty, having a maximum tractive effort of 50,000 lb, or burning upwards of 4,000 lb of coal per hour for an extended period, should be equipped with a mechanical stoker. Of course, in excessively warm climates, or at high altitudes, where manual stoking is exhausting, the practice may be profitably applied to locomotives of smaller dimensions.

It is necessary to point out that the mechanical method of firing the locomotive does no more than relieve the man of arduous work. It is not a fuel-economizing device, in the strict sense of the word, despite the fact that a saving in the fuel bill has been revealed as the result of this method of raising steam. But it has been proved that a locomotive so equipped will haul from 15 to 20 per cent, more tonnage than one which is hand-fired over the same road under identical conditions.

Although the mechanical stoker is practically depriving the fireman of his essential job, it is to the distinct advantage of the man and the efficiency of the locomotive in general. This method of firing is not only cleaner and easier, but it enables the fireman to assume more responsible duty and conduces to the enhanced safety of the train. Two men are available to watch the signals. Finally, the fireman has the opportunity to acquire a superior training for his ultimate position of driver.

SETTING THE DUPLEX STOKER. The engine which drives the stoker is seen on the left at the base of the unit. A huge “Mikado” locomotive carries the device.

You can read more on “The Development of the Fire-Box”, “Locomotive Accessories” and “The Locomotive Booster” on this website.

Under concentrated study and experiment evolution was rapid. In the course of two or three years there was a multiplicity of appliances for mechanically firing the locomotive. This activity was enthusiastically stimulated by the railways, and facilities for subjecting the various conceptions to trial were readily granted, but the great majority have been found wanting. The result is that, to-

Under concentrated study and experiment evolution was rapid. In the course of two or three years there was a multiplicity of appliances for mechanically firing the locomotive. This activity was enthusiastically stimulated by the railways, and facilities for subjecting the various conceptions to trial were readily granted, but the great majority have been found wanting. The result is that, to-

The tender component consists of a heavy wrought steel trough, fitted with a helicoidal screw, which moves the coal, falling into the trough, forwards, into the crushing zone with its crushing plate, where the lumps are reduced to the desired size. This unit does not belong to the tender but to the engine, so that when the connecting gear is released, to allow the tender to be drawn back, the latter comes clear of the stoker-

The tender component consists of a heavy wrought steel trough, fitted with a helicoidal screw, which moves the coal, falling into the trough, forwards, into the crushing zone with its crushing plate, where the lumps are reduced to the desired size. This unit does not belong to the tender but to the engine, so that when the connecting gear is released, to allow the tender to be drawn back, the latter comes clear of the stoker-