© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The Southern Pacific Railroad

The story of the foundation and development of the Southern Pacific system

THE MOST MODERN PASSENGER LOCOMOTIVE (4-

THE first iron-

The conversations revealed one great difficulty: it would never be possible for the Californians to carry out the project with their own resources. Why should not the Government co-

Shortly after his return to the Pacific coast Dr. Strong and Judah came to the conclusion that the hands of the Government could be more satisfactorily forced by the Californians taking their courage in their own hands to launch the scheme. Dr. Strong thereupon introduced the young engineer to the four big men of California, Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker and Collis P. Huntington. They became so profoundly impressed as to incorporate, on January 28, 1861, the Central Pacific Railroad, with a capital of ,£1,700,000; of this sum, however, only a bagatelle of £29,000 was subscribed, and that for the most part by the enthusiasts themselves.

Judah again went to Washington to importune the Government, and so convincingly demonstrated the imperative necessity for government financial aid as to influence the passing of the historic Act of 1862, authorizing the construction of the first transcontinental railway. Although the Act defined the constructional limits of the Californian company to a point approximately half-

The Californian pioneers, once official co-

The subjugation of the formidable mountain range within this period testifies to the energy with which the work was pursued. It had to be executed wholly by shovel and pickaxe, with gunpowder as the agent for shattering the rock, dynamite not then being known, though nitro-

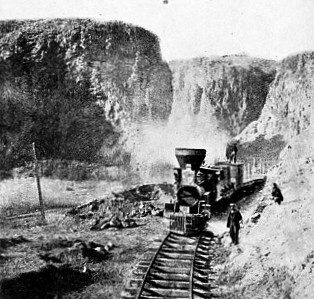

TYPICAL SCENE DURING THE CONSTRUCTION of the Central Pacific (now Southern Pacific) line across the Sierra Nevada mountains.

Unfortunately, the pathfinder, whose efforts had been mainly responsible in rousing the Government, was denied the glory of seeing his life-

In the first instance it was suggested that the trans-

Although the forces behind the enterprise did not release the driving pressure advance was sternly disputed: gunpowder did not prove a serviceable weapon with which to wage war against the rock. The first forty miles led to the climax. In Bloomer Cut, the gunpowder was completely defied; the advance slowed down to such a degree that the shareholders’ enthusiasm sank to zero, and the public grew mirthful over “The Dutch Flat Swindle”.

As the granite laughed at gunpowder it was decided to ascertain what “blasting oil” could do. But nitro-

The Chinese, to whom was given the honour of mixing the chemicals, were provided with a special shanty for the purpose, and the mixing shack was generally set at a comfortable distance away. On one occasion the nitro-

The winter of 1867 was a nightmare to the constructional gangs at the rail-

The season proved abnormally severe with intense cold. Two camps of Chinese, engaged in driving two tunnels, and another gang occupied in building culverts, were accommodated in Strong’s Canyon. The snow-

To the east, between Blue Canyon and Cisco, where the line makes its sinuous way through deep cuttings, worse troubles were being encountered; all constructional work, except in the tunnels, had to be abandoned. The snow was in constant movement, bringing down rock, trees, and detritus in huge streams, filling the deep cuts. As steam shovels were unknown, these cuttings had to be cleared by hand.

To this day snow ranks as the railway’s greatest dread during the winter. When the rails were laid across the summit, the engineer turned to the devising of ways and means to keep the narrow steel channel open while Arctic weather reigned. Investigation and experience have provided only one feasible solution: to encase the steel highway in a wooden shed throughout the whole length of the affected zone.

DOUBLE-

The snow-

A few years ago the exigencies of increasing traffic necessitated doubling the line through the mountains, with the exception of the stretch over the summit. On the Pacific slope the second road is carried only as far as Blue Canyon, at an elevation of 4,693 feet. At Blue Canyon, the western entrance to “the longest house in the world”, the station is set on a curve of such sharp radius that a train of 45 vehicles completely encircles it. At this point the waiting mammoth Mallet helper, weighing 437,000 lb., is picked up to give the passing train a lift over the vertical rise of 2,324 feet through the snow-

As the result of absorption the Central Pacific Railroad, as such, disappeared in its corporate capacity, to become the Sacramento Division, one of the ten sections into which the huge network forming the Southern Pacific is divided. The other divisions are respectively the San Joaquin, Los Angeles, Coast, Western, Stockton, Atlantic, Mount Shasta, Portland, and Tucson. Each might be described as a complete railway in itself, serving a specific territory, comparable with the components of the four groups into which the railways of Great Britain have been compressed, yet interconnected and with free running. With the exception of the Central Pacific, however, the other divisions represent new construction, except in so far as various sections of privately owned, independent lines were leased or purchased to complete the great scheme conceived to criss-

Flushed with the success of the first venture in big scale railway-

Furthermore, it spanned the continent far to the north. Huntington aspired to connect San Francisco direct with the Atlantic coast, and he realized that the most attractive way across the continent would be well to the south, practically paralleling the United States-

At the time this enterprise was assumed — the “70’s” — it represented an even more daring railway-

Huntington, Crocker and their colleagues were weighing the advantages and disadvantages of two possible routes, the one from Mojave via Needles and the other from Mojave by way of Los Angeles, when two prominent leaders of the latter city secured audience of Huntington, then president of the Central Pacific, and succeeded in persuading him to embrace the second route, thus bringing their city and its surrounding fertile valleys into touch with Sacramento and the transcontinental. The alternative route via Mojave and Needles was subsequently embraced by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe to carry its metals to the Pacific coast.

Development of the Southern Pacific

The Los Angeles territory was certainly full of promise. Its railway subjugation had been commenced through the initiative of an energetic pioneer, Captain Banning, who, in 1868, had commenced the building of the Los Angeles and San Pedro Railway, the material for which had been brought into the country by way of Cape Horn. Huntington acquired this line for consolidation with the newly created Southern Pacific.

While the main line was being built southwards to Los Angeles, the short line commenced by Banning was extended to meet it, junction being somewhat delayed by the driving of the big tunnel at San Fernando. The latter, however, was not permitted to retard the advance towards the Atlantic seaboard, for the railway builders swung their line round towards the Colorado River which they reached in 1877. The breadth of the waterway at this point held up the rail-

As this country gave no promise of becoming revenue-

Heavy climbing commenced when Gila was passed and continued for 18 miles, to be followed by a drop to what was then the flourishing town of Heaton, but whose glory has completely departed. At this point the engineers introduced what was, and probably still ranks as, the longest curve in the world — 5 miles in length — advancing the line to Maricopa, and, to enter a tangent, 47 miles in length, the longest stretch of straight line upon the whole system.

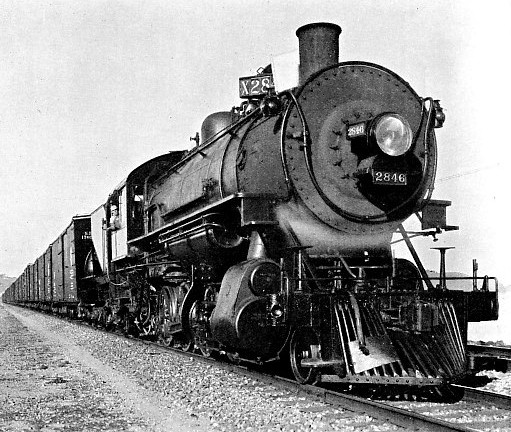

TYPE OF FREIGHT LOCOMOTIVE used on the coastal section of the Southern Pacific Railroad between San Francisco and Los Angeles, in 1922.

In 1880 the metals reached Tucson, a hive of prosperity buried in the heart of the desert. On a steadily rising grade the rail continues from Tucson to Vail, 20 miles to the east, where it penetrates the Cienega Canyon, through which for quick, cheap construction, the metals were laid on the flat low-

In fact, for some distance through this bad country the recurring wash-

Swinging down from the summit the railway traverses the country which, since the Apaches roved North America, had been regarded by the Apaches to be their undisputed domain. After many years of incessant warfare the government succeeded in concluding a peace treaty with this warlike tribe in 1872, which was faithfully honoured by the chief until his death in 1876. His successor, the notorious Geronimo, declaring the compact to be terminated by the death of the Apache signatory, rallied the tribe which, breaking out of the reservation, went on the war-

The Southern Pacific cut across the centre of the valley to which the Indians laid claim, and it was war to the knife between the railway-

Leaving the Indian country the line overcomes the succeeding mountain range at “Raso” — “Railroad Pass” — to run downhill to Bowie. Then commences the uphill pull at 1 in 75 to Steins, the railway summit of the Peloncillo Mountains, at 4,378 feet.

Dropping down the eastern slope the railway cuts across the Playas Valley to Lordsburg, whence commences the long pull, with a ruling grade of 1 in 100, to the summit-

holds a unique distinction. It crosses the backbone of the United States at a lower elevation than any other transcontinental railway, while the approaching grades are appreciably easier, and in striking contrast to those of the great lines farther to the north. Through the succeeding 90 miles the line steadily falls, except for one short rise with a ruling gradient of 1 in 100, to El Paso, at 3,777 feet above sea-

The Tucson Division comprises 704.88 miles, of which 560.65 miles represent main line. At five places on the eastward run, and four on the westward journey, helper locomotives have to be used to assist the passing trains over the humps; the longest section is that encountered when going east — 70.6 miles between Tucson and Dragoon — to overcome the 2,226 feet difference in elevation between these two points.

At the western end of the Tucson Division junction is made with the San Joaquin Division, which may be described as the link between the northern and southern sections of the system, although it is an impressive connexion of 245 miles of main line.

It was in 1876 that the San Joaquin Division, the continuation of the desert section through southern California, was opened for traffic. Construction did not present any great difficulty until the engineer drew towards the Tehachapi mountain range, where he was brought to a full stop. The problem was to find a working grade overcoming the 4,000 feet difference in altitude with reasonable development work. When the pathfinder first tramped the range he was perplexed by the maze of heavy cuttings and high embankments required to assure adhesion working; the cost of these he calculated would be at least £200,000.

Little wonder the engineer paused to profit from the axiom, “make haste slowly”.

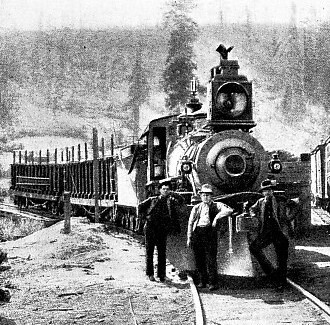

FIRE-

It was Chief Engineer Hood, the doyen of American railway-

This he accomplished by what is now known as the “Tehachapi Loop”. If one draws two large circles upon a sheet of paper, one inside the other, but connected so as to form a spiral, and with the periphery of the inner shooting out to one side, one has the plan of this ingenious development. The line comes up the mountain side, and, upon reaching the top, describes practically a complete circle, and then sets out to describe another and smaller circle within, finally swinging off to enter a ravine to descend the western slope of the range. In this manner the engineer overcame the task of scaling 4,000 feet in 46 miles, although it compelled him to introduce a climb of 1 in 45.

In making the distance the line runs through 18 tunnels, totalling 8,240 feet in length, doubles and redoubles across the Tehachapi Creek seven times, and negotiates 8,300 degrees of curvature. To move a train of 56 vehicles round the loop requires the combined effort of three 175-

The mountains have been surveyed time after time in the effort to obtain an easier road but without avail. The circumstance that no other economic method of overcoming the difficulty is possible was proved by the fact that the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe, upon approaching the Pacific coast, were unable to discover the alternative and so completed an arrangement with the Southern Pacific Railway for running rights over this loop into Lower California.

The “Tehachapi Loop”, alternatively known as “Hood’s Spiral”, is probably the hardest worked single track mountain line in the world. As many as 1,287 ponderous American freight cars have been moved, in both directions, over the loop in the course of the twenty-

In 1901 the Southern Pacific opened a new line of about 300 miles following the coast between San Francisco and Los Angeles. The forging of this link occupied no less than 38 years; its foundation was the little line known as the San Francisco and San Jose Railway, which crept out from the city by the Golden Gate in 1863 a few miles to the south. This, in due course, was absorbed by the Southern Pacific, to be prolonged by fits and starts to the southern city. The spasmodic construction was due to the somewhat difficult character of the country traversed, varying from stretches of marsh to wastes of sand, yawning ravine, towering mountain and wild seashore.

While the outstanding engineering achievements upon this road are of a vastly different character from those encountered among the mountains, they are impressive and arresting from their variety. At one point, to cut out 1.6 miles of distance, the engineer planned the Bayshore cut-

The Los Angeles line winds through the gloomy depths of the Pajaro Canyon and climbs to the heights of the Santa Lucia Mountains, forcing the barrier by way of the Cuesta Pass. For mile after mile it passes through scorched drifting sand, and to prevent this moving upon and burying the track, over 800 acres of bent grass and acacia trees have been planted; at the point where the track swings to the seashore it was necessary to throw up a massive seawall for 8,200 feet to protect the line, the cost of this work alone being £16 per lineal foot.

The weaving of a steel network through central and southern California naturally prompted the scheming of a similar fabric through the northern reaches of the state, particularly as there arose the demand for more direct communication between Portland and San Francisco than was offered by the sea-

The end of steel was picked up at Gerber, to be carried north 220 miles to Ashland, in Oregon, but it took sixteen years to forge this link, which suffices to reveal something of the prodigious difficulties encountered. The road was practically pushed on in easy stages; the first was completed in 1871; and the last section of the main line in 1887, the branch line of 126 miles from Weed to Kirk being completed in 1905.

From the engineer’s view-

The toll of the grade upon locomotive power is heavy. Five locomotives merely represent the motive power required to handle an average freighter from Ashland, the junction of the Shasta and Portland divisions, en route to San Francisco. If a more than usually heavy train comes down from the north, the locomotive department has to provide seven or eight giants, three for the head of the train, two or three in the middle, and two as pushers.

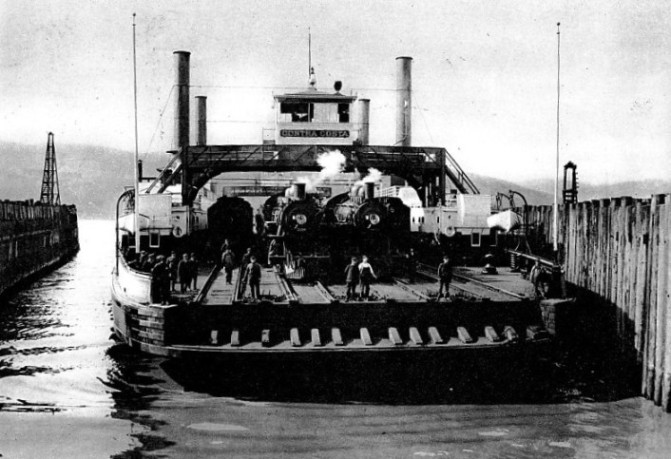

THE LARGEST TRAIN FERRY IN THE WORLD. The Contra Costa carries the Southern Pacific trains between Oakland and San Francisco. It transports in one trip, 2 locomotives, 18 passenger coaches, and 32 freight cars.

When Siskiyou is reached, three of the locomotives are dropped, to return to Ashland to give assistance to the next train, but the double-

That the Shasta Division is composed of a chain of “S’s” is obvious from the fact that there are 100 miles of curved main line out of the 220 miles forming the division. There are more than 820 curves ranging from 5,730 to 409 feet in radius, and 27,470 degrees of curvature in all. As there are 360 degrees to the circle, it will be seen that in making the run between Gerber and Ashland the train turns round completely no fewer than 76 times ! And over this amazing stretch, with its twists, tunnels and toil the whole way, the locomotives move more than 350,000 tons a month.

From Ashland the railway continues its way through the length of Oregon to Portland, the great port of the state upon the Columbia River, traversing country rich in romantic stories of the long ago, when the hardy pioneers from the East made their way with difficulty, suffering, and privation over what has become known as the “Oregon Trail”.

At Portland the railway tracks are only a few feet above sea-

So far as the Oregon Division is concerned, the most spectacular engineering achievements are to be found off the main line, notably on the road to Tillamook, which crosses the coast range at right angles. Although the summit-

The Portland Division is notable for having more timber trestles than any other section of the system; the total length of such structures amounts to 46 miles, one of which, crossing Baldwin Creek, is the highest in the United States — 186 feet. But the fire hazard is so pronounced that it has led to the conversion of all timber work into solid embankments, the trestling being buried in the process of discharging the spoil from rail level. On this division is another interesting piece of work —a bridge with the longest wooden draw-

A vital link in the smooth rhythmic working of this huge railway network is the ferry system across San Francisco Bay, between Oakland and San Francisco. The Southern Pacific maintains the largest system of this character in the world, moving 75,000 people to and fro every day throughout the year. The fleet comprises thirteen craft, to man which requires 600 employees, including 36 captains and 130 firemen.

Pride of place is occupied by the Contra Costa built at the company’s yards at a cost of about £100,000 for the transport across the straits of complete trains, including locomotives. It is of sufficient dimensions to handle, in one trip, two locomotives, 18 passenger coaches, and 32 freight cars, and shares this duty with its sister, the Solano, of only slightly less carrying capacity. From their duty these craft have become colloquially, yet aptly, known as “The Water Trains”. During the year they make about 14,000 trans-

The system is still growing. Even during the years of the Great War an important new road, the San Diego and Arizona Railway, 148 miles in length, was built as the joint enterprise of J. D. and A. B. Spreckels, the well known American financiers, and the Southern Pacific, by whom it is equally owned, though the last-

The railway, starting from San Diego, bears due south, crosses the frontier at Tia Juana, and traverses Mexican territory approximately parallel with the boundary, never venturing more than 10 miles from the latter, as far as Lindero. Here it re-

The heaviest engineering work was encountered in the Carriso Gorge, which is threaded for 11 miles, the cost of which totalled £787,820, or approximately one-

The growth of the Southern Pacific, during less than half a century, from the little 22 miles “one-

THE FIRST AND LATEST LOCOMOTIVES ON THE SOUTHERN PACIFIC SYSTEM. The giant “fourteen-

You can read more on “America’s First Trains”, “Giant American Locomotives” and “Southern Paxific Locomotive Development” on this website.