© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

North American Railroads

Vast Systems Which Span a Continent

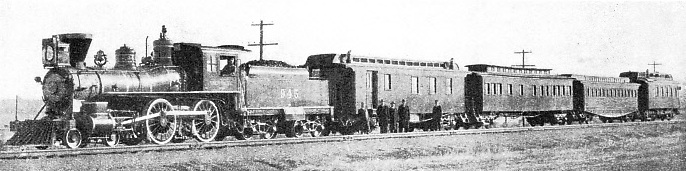

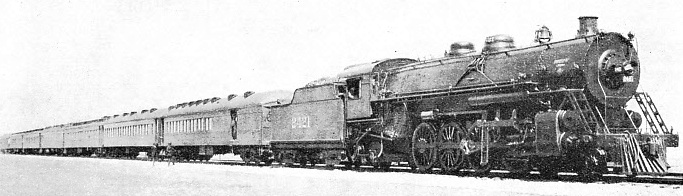

THE “EMPIRE BUILDER”, one of the crack expresses of the Great Northern Railway of America. The train operates between St. Paul and Seattle. This illustration shows the celebrated “flyer” leaving the Union Station yards at St. Paul, Minn.

THE building of the first railway across the United States of America provided some of the most dramatic episodes in the history of that country. The story of this line, the Union Pacific Railway, is indissolubly bound up with the traditional elements of the “Wild West” -

More than a century ago men had dreamed of a great highway right across the continent of North America. In the year 1803, the vast tract of French territory, known as Louisiana, lying between the Mississippi River and the giant mountain range of the Sierra Nevadas, was sold by Napoleon Bonaparte to the Eastern States of America.

After this “Louisiana Purchase” the idea of the transcontinental route took a firm hold on the American mind and several expeditions were organized, beginning with John Jacob Astor’s venture across the continent in 1810.

The Astor expedition and many later enterprises followed the courses of the great American rivers, and the hardships and distances involved further strengthened the conviction that a direct overland route was essential.

The famous “South Pass” across the Rocky Mountains was discovered by the pioneers Ashley and Provost in the winter of 1823-

After the settlement of the Oregon boundary dispute with Canada, the acquisition of California from Mexico in 1848, the Mormon settlement of Utah, and the discovery of gold on the western seaboard, the need for rapid transport from east to west could no longer be denied.

After much preliminary discussion and many surveys, a Bill was submitted by S. A. Douglas to Congress in 1855, proposing three routes to the Pacific coast. Of the proposed routes, one was to be via El Paso and the Colorado River -

The Douglas Bill was not approved by Congress, but with the coming of the Civil War matters were expedited by the passing of an Act creating the Union Pacific Railroad Company on July 1, 1862.

IN THE EARLY DAYS of the Union Pacific Railroad. This photograph is of a replica of a Union Pacific train in the middle ‘sixties. The wooden coaches had especially narrow windows so as to offer as small as possible a target to Indian arrows and bullets. Each train carried a community stove, where cooking was done. Bedding, if any, was owned by the passengers.

The Act authorized the construction of a railway from the Missouri River to the Pacific coast. The building of the line was to be undertaken by two companies. The Union Pacific Railway was to advance westward from the Missouri and the Central Pacific eastwards from the Pacific coast. The two railheads were to meet and be connected on the California-

It was stipulated that if the Missouri River was not in railway communication with the head of navigation on the Sacramento River by July 1, 1879, then the whole of the completed portion of the line, together with all rolling stock, material, buildings, and land were to be forfeited to the United States Government.

The 1862 Act also decreed that the gauge, route, and starting point on the Missouri River were to be decided by the President of the USA. It was decided that the gauge, maximum curvature, and gradient were to be the same as on the Baltimore and Ohio Railway.

Although the essential details of the scheme were completed without difficulty, serious delay arose in connexion with the question of gauge.

In the early ‘sixties railway gauges varied to a considerable extent. In Great Britain there existed both the broad and the standard gauge. The continent of Europe was similarly undecided, and in the United States opinions were divided. The Erie and other lines had a gauge of 6 ft. Railways in Missouri had chosen a 5 ft 6-

5 ft gauge of their own. President Lincoln was in due course asked to determine the gauge, and he chose the 5 ft for both eastern and western sections of the line. Such a decision naturally led to opposition from the Eastern States, where an overwhelming preponderance of mileage was of standard gauge. Finally the matter was settled by Congress, and a Bill, passed on March 2, 1863, fixed the gauge for both lines and for all branches at the 4 ft 8½-

Another difficulty encountered by the railway company was the choice of a starting point on the Missouri River. The President of the United States was entitled to settle this matter, and he selected a terminal on the east bank of the river, known as Council Bluffs, opposite the present city of Omaha. The Chief Engineer of the company, however, had a strong preference for a site seven miles to the south, but finally the people of Omaha had their way and the construction of the line was begun on December 2, 1863. In that year, however, the American Civil War was raging, and little work was done on the Union Pacific Railway until the spring of 1865. Despite the war, however, construction was carried on, but in conditions of great difficulty. Labour was naturally scarce, as nearly every able-

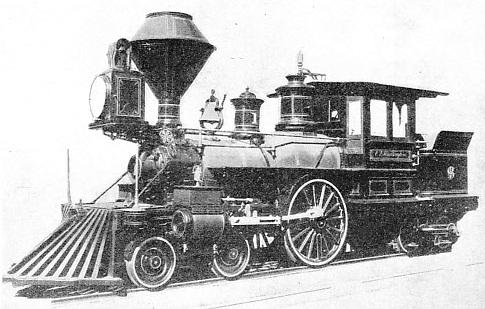

LOCOMOTIVE “C.P. HUNTINGTON” was the third placed in service by the Central Pacific (now Southern Pacific), and was named after the first vice-

The route of the Union Pacific lay through country devoid of constructional material except ballast for the track. Some six and a quarter million sleepers, or ties, were required, and these had to be felled and cut in the forests of Pennsylvania, Michigan, or in the South, hundreds of miles away from the railway.

In addition, over 350,000 tons of steel rails and of steel for other purposes were needed. This material had to be hauled overland, at tremendous cost, by oxen.

The supply of men and materials was not the only difficulty encountered. Money was scarce and private investors were reluctant to advance financial support for building purposes. Eventually the Government was compelled to assist by doubling the land grant, by permitting the railway company to issue first mortgage bonds, and by agreeing to forgo its rights of a first charge on the property. The Government also enforced the surrender of a strip of ground, 200 ft wide, for the right-

The railway company’s Chief Engineer, Mr. Dey, retired from his position in 1865. He was followed by Mr, Ainsworth, with

J. E. House as Engineer in charge of the construction work. The line was run by House through the Platte Valley, and the survey was so brilliantly accomplished that it has never been necessary to make any material alterations in the alinement. This portion of the line remains as one of the most perfect stretches of the Union Pacific system, and it has been double-

Through the “Wild West”

The building of the railway across the plains proved one of the most thrilling dramas enacted on the American, or on any continent. In the early ‘sixties the “Wild West” lived fully up to its reputation, and more than one novelist has laid his scenes among the railhead camps of the construction gangs and the vast open spaces on the prairies. Practically every yard of the way across the plains was challenged in no uncertain manner by the Indians, left in supreme control of vast territories after the Civil War.

The construction gangs found their labours interrupted and enlivened by many a sanguinary encounter with warring Indian tribes, such as the Pawnees, Sioux, and Arapahoes, and, farther west, the Crows, Black feet, Barnocks, and Shoshones. So serious did the menace become to both settlers and railway builders that eight military forts had to be established, some of which are still in existence.

Mile after mile of the track was laid under the rifle fire of warriors on the warpath. Platelayers and construction engineers again and again would be compelled to drop pick and shovel for revolver and repeating rifle. The encircling tactics of the red men, clinging to the off-

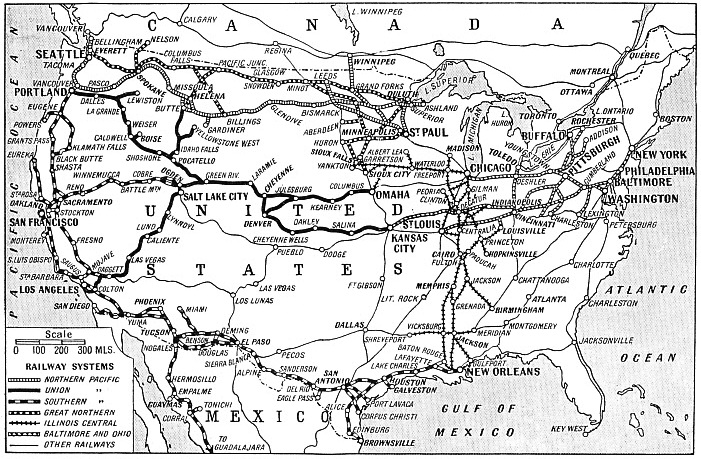

SOME OF THE PRINCIPAL SYSTEMS of the United States of America are indicated on the above map, which shows their main lines. The Union Pacific operates 3,768 miles of track, the Southern Pacific 8,791, the Northern Pacific 6,736, the Great Northern 8,328, the Illinois Central 6,857, and the Baltimore and Ohio 6,440 miles.

Guerrilla war was carried on for a long time until the railhead had drawn away from the plains to the foothills of the Rockies. Finally peace was concluded between the Indian chiefs and the President of the United States in person, and the railway work proceeded without molestation.

Gun play, however, was not confined to the breaking of Indian attacks. The temporary headquarters of the construction gangs became timber-

For a long time, however, even after the completion of the railway, lawlessness reigned in the western towns. These became the meeting places of the cowboys driving immense herds of cattle from the south-

The difficulties of the Central Pacific line were of a more geographical character. Under the driving influence of Theodore D. Judah and his associates, prominent San Francisco tradesmen who afterwards became millionaires, the Central Pacific track was pushed forward up the western slopes of the Sierras. Water courses were followed, steep precipices were skirted, and the summit of the range was gained at a height of over 7,000 ft. Down the eastern slopes the line was laid through deep canyons, and thence across the desert stretches of Nevada towards Salt Lake.

The building of the Union Pacific was carried on in the face of all difficulties by General Grenville M. Dodge and his assistant, Dr. Durant. Two other men whose efforts did so much to further the construction of the United States first railway were the brothers Oliver and Oakes Ames. The brothers invested more than a million dollars of their own money in the railroad. Oakes Ames was intimately associated with the construction work of the line from August 16, 1867, when the track had been carried to a point 247 miles beyond Omaha. With such skill and vigour did Ames attack his task that in 633 days he had added another 839 miles of track to the railway -

With the Central Pacific track steadily pushing eastward and the Union Pacific Railway progressing to the west, it ultimately became necessary for the two systems to be linked up. The original charter granted to the Union Pacific Railway defined the eastern boundary of California as the point to which the line was to be carried for union with the Central Pacific line.

This arrangement was subsequently modified, and the Central Pacific was permitted to continue its advance eastwards to meet the Union Pacific. The Central company resolved to carry the track to Salt Lake City, earning as much of the land grant and subsidy as possible.

The two advancing railheads met in Western Utah during the winter of 1869. But they did not stop and link up. The construction gangs passed one another and continued to lay parallel tracks. For week after week the railheads receded rapidly, leaving a double set of metals side by side across the prairie.

The situation was not without an element of humour, but obviously a halt had to be called, and finally an agreement was reached between the two companies. The Union Pacific track had reached a point 225 miles beyond the meeting-

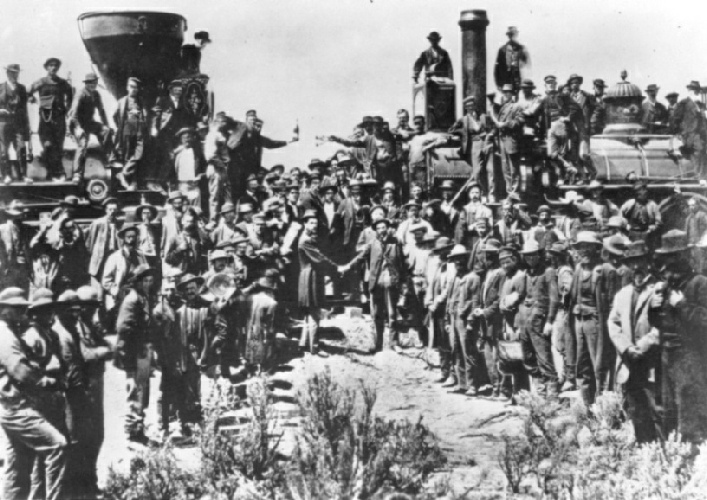

AMERICA’S FIRST TRANSCONTINENTAL RAILWAY. This picture shows the celebration of the linking of the Union and Central Pacific Railways. Through connexion was established in 1869 between the Missouri River and the Pacific coast.

Through communication was effected between the Missouri River and the Pacific coast on May 10, 1869.

The driving of the last spike joining the Union Pacific to the Central Pacific railroad ranks as one of the most important events in the whole history of the United States. This great task was accomplished in three years, six months, and ten days. From that time the railroads of America were expanded in every direction, branch lines were built to distant districts, and a steady improvement in operation in locomotives, rolling stock, and equipment was begun. This has continued progressively ever since.

A number of smaller railways serving the district along the route of the Union Pacific line were in due course incorporated with the larger company. One of these railways was the Levenworth, Pawnee and Western, which was begun in the year 1855. In 1880 this line was incorporated with the Union Pacific. At the same time the Denver Pacific line was added to the great transcontinental railway.

On the main line of the Union Pacific a number of important works were carried out. Chief among these was the great bridge over the Missouri River, enabling the railway to cross to the city of Omaha. The building of this bridge was entrusted to General Dodge, who prepared the plans.

The company was authorized to issue bonds to the extent of £500,000 and, although a preliminary contract was entered into in 1868, involving a cost of nearly £218,000, work was suspended for a few months, and a second contract for an improved bridge was drawn up, with a figure of £350,000 as the price of construction.

Cyclone Havoc

The bridge consisted of eleven spans, each of 250 ft, on which the track was laid at a height of 60 ft above high water. During the night of August 4-

By 1870 the Union Pacific owned some 150 engines and about 2,500 coaches and wagons. After a period of forty years the rolling stock had increased to 660 locomotives and over 16,550 wagons and coaches of all types. The incorporation in the parent Union Pacific Company of a number of subsidiary lines had resulted in financial loss, and on October 13, 1893, the company placed its affairs in the hands of a receiver for the purpose of complete reconstruction. On January 1, 1897, the present Union Pacific Railway Company was formed to purchase and operate the railways under the jurisdiction of the former concern. This enormous sale of interests, the biggest auction on record, was held in front of the Goods Station of Omaha on November 1, 1897, and the price paid by the new corporation was over eleven and a half million pounds.

Some of the most striking improvements on the Union Pacific system were begun in 1899. Double-

An interesting link with the early days of the railway was provided by the completion of the “Lane cut-

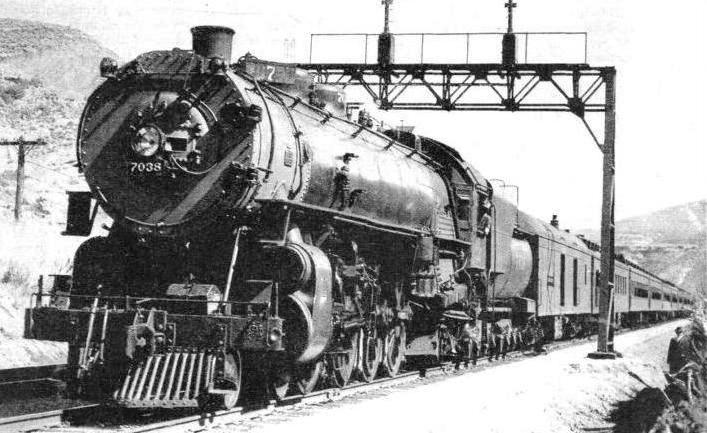

IN ECHO CANYON, UTAH. The “Los Angeles Limited” express, operating daily on the Union Pacific system between Chicago and Los Angeles. The train includes observation car, lounge car, and standard Pullmans, with a choice of drawing-

Enormous construction works were necessitated in the building of the line, as wide valleys had to be spanned, and long, deep cuttings were involved through hills and high ground. Some of the embankments were of huge dimensions, and among the cuttings was one 85 ft deep, 437 ft wide, and no less than 5,300 ft in length. It is said that in the building of this twelve miles of route over four million cubic yards of earth had to be shifted, and the total cost was more than £600,000. The reorganization of the great railway workshops at Omaha and the installation of automatic signalling along 1,250 miles of main line cost together nearly another million pounds.

An interesting point in connexion with the ballasting of the new track was the use of a special gravel found in the vicinity containing an appreciable percentage of gold. It is said that this Sherman gravel, as it is called, would yield, if treated, about eight shillings in gold for every ton of the material.

Possibly the most spectacular achievement in the reconstruction of the line was the building of what is known as the “Lucin cut-

Salt Lake is so saturated with mineral that it is impossible for a bather to sink in it. The Union Pacific’s track on its way westward to Ogden, on the eastern shore of the remarkable lake, also swung northwards towards the original meeting place of the two systems at Promontory.

Unfortunately a mountain range runs right down to the water’s edge on the northern shore, so that to negotiate Prom-

The Lucin “Cut-

On both sides of Promontory Point, also, the grade was of a switchback character. The 147½ miles between Ogden and Lucin were negotiated by powerful locomotives placed at the head of the trains and assisted by others at the rear and in the centre. The cost of hauling traffic over this section of the line soon began to mount up. Finally the engineers suggested that, as the Salt Lake was only thirty miles wide, in a straight line between Ogden and Lucin, and with a depth of only 30 ft, it would be possible to build an enormous bridge right across it to carry the track.

This plan had been proposed long before Mr. Harriman’s presidency, but under his guidance it was brought into operation in an improved form. The original scheme involved the use of timber trestles for practically the whole distance over the water; but finally it was decided to reduce the extent of open woodwork to twelve miles, filling in the trestles of the remaining distance with earth to form a solid embankment.

The rail level is 17 ft above the water, and the top of the embankment 16 ft wide. To secure the enormous amount of timber necessary for the undertaking large tracts of forest were purchased in Louisiana, Texas, Oregon, and California for the supply of logs ranging from 100 to 150 ft in length. Huge steam shovels played their part in preparing the earthwork, and a stern-

Work continued both by day and by night, the necessary illumination being provided by powerful electric lamps. Over 3,000 workmen were engaged on the task, and at times over 400 car loads of ballast were sent seawards during the daytime. Supplies of fresh water presented another problem, as every drop had to be hauled over a hundred miles of desert. This was a tremendous task, as the daily supply amounted to 336,000 gallons of fresh water.

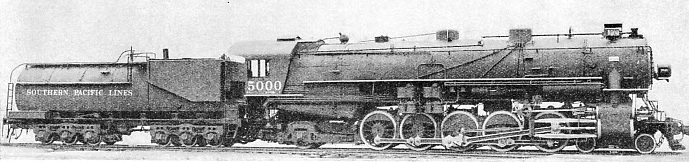

ON THE SOUTHERN PACIFIC, a three-

Huge pile-

Each “bent” is connected to its fellow on either side by eleven heavy baulks laid parallel to the track. The road-

At the present time the Union Pacific Railroad owns 3,768 miles, all on the standard gauge of 4 ft 8½-

The Central Pacific Railway now forms part of the Southern Pacific system, which, lying wholly in the western states, operates nearly 8,800 miles of track. On the Southern Pacific system there are more than 1,480 locomotives 1,690 passenger cars, and over 52,000 freight and other cars, including some 4,000 devoted to special services.

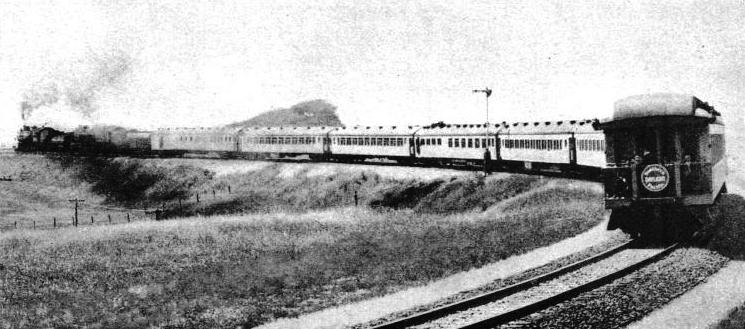

THE “DAYLIGHT” EXPRESS, on the Southern Pacific’s line, is one of the chief trains on that system. It links San Francisco and Los Angeles, a distance of 471 miles by the route taken. This train includes an observation car with a large open-

Another large system is the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe, which constitutes one of the principal links between Chicago and the coasts of the Southern Pacific and the Mexican Gulf. There are over 9,500 miles of track, and it is over the lines of this company that the famous express the Santa Fe “Chief” makes its daily journey. This train is illustrated and described in the chapter beginning on page 281.

In the Southern States is the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, with over 5,100 miles of track, 840 locomotives, over 500 cars and some 31,000 freight wagons of all descriptions.

An important railway in the Eastern States that serves the coal-

Another railway leading out from Chicago is the Chicago and North Western line, with over 8,470 miles of track, 1,678 locomotives, three Diesel electric locomotives, nearly 2,000 passenger cars, including a number driven on the petrol-

Another important line also leading out from Chicago is the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad. It is over the lines of this railway that the famous American train the “Zephyr” operates, and a reference is made to this in the chapter “Speed Trains of North America”.

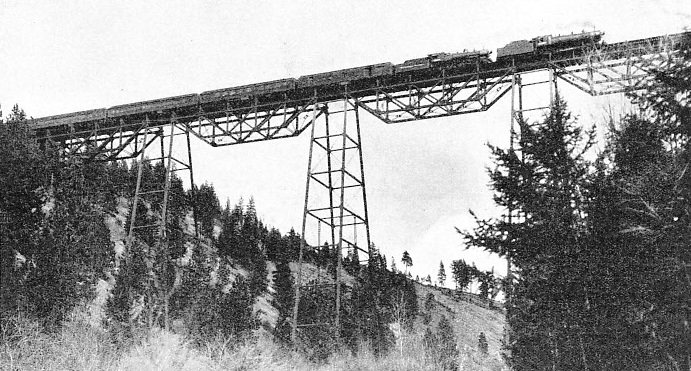

THE “NORTH COAST LIMITED”, a transcontinental express, crossing the Marent Viaduct, west of Missoula, Montana. The train operates over the metals of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad, the Northern Pacific Railway, and the Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway. It links Chicago with cities in North-

One of the most remarkable lines in the United States of America is the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific, on which operate some of the largest electric locomotives in the world. Of the 10,400 miles of track over 660 route miles through the Rocky Mountains have been electrified, and the traffic is dealt with by sixty-

The continent of North America has presented to the railway builder some of the greatest difficulties encountered by man in his conquest of nature and the spanning of immense distances.

The linking of the Atlantic coast of the United States with the Pacific seaboard had been in men’s minds from the early days of the nineteenth century, and in 1844 a wealthy American, Asa Whitney, vigorously attacked the whole problem. Whitney devoted all his energy and resources to arousing public interest in the construction of a railway across the Northern States from coast to coast. Unfortunately the whole of Whitney’s fortune was absorbed in these efforts, and it is said that he spent the rest of his days working as a milkman. Whitney’s work had, however, borne fruit, and a brilliant engineer, Edwin F. Johnson, was so fired by the former’s enthusiasm that he ultimately persuaded the Government to sanction surveys for the enterprise.

The Pacific Railway surveys proved a momentous undertaking, and five expeditions were dispatched to .the coast to find the easiest route for the railway over the Rocky Mountains. The reports compiled by these pioneers, summarized in thirteen volumes, were submitted to the Government in 1855.

Another Transcontinental Route

In 1862, after considerable academic discussion had been expended on the reports, the State of California demanded railway communication with the Eastern States. The Government, on California’s threat to secede from the Union, sanctioned the building of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railways, as related earlier in this chapter.

This decision was at the expense of the northern scheme propounded by Whitney and Johnson, and so uncompromising was the latter in his attitude that the Government agreed to the building of a Northern Pacific Railroad. The Act of Congress authorizing the line was signed by President Lincoln on July 2, 1864, two years after the Act creating the Union Pacific Railroad.

Under Johnson’s leadership the necessary surveys were made and the route decided upon. The American Civil War, how-

During the war, an obscure banking house -

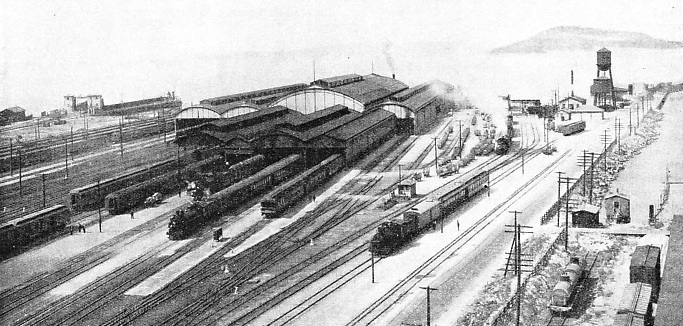

ON THE SOUTHERN PACIFIC SYSTEM. Oakland Pier Terminal, in California, looking west across San Francisco Bay towards the city of San Francisco. There is a train ferry across the bay operated by the railway company, and the berth can-

It was by no means an easy task to persuade investors to subscribe to the funds of the railway, as the prospects of profitable working seemed, at that time, somewhat remote. In 1870, the territory in which the new railway was to be built, had a population of only 600,000. Of these, some 400,000 were in the State of Minnesota, and the remainder were scattered in small communities throughout the other states along the route, sharing the land with the Indians and the buffalo herds. It is not surprising that critics were in doubt as to the source from which the railway was to derive its traffic.

Supported, however, by the funds raised, the railway builders began work, and from a point twenty miles wrest of Duluth in Minnesota, the track was pushed forward to the Pacific. By the end of 1870 the railway had been laid as far as the Red River in Minnesota. Simultaneously with the drive to the Pacific, a start had been made in the far west to build a line running eastward to meet the railway from Minnesota. The western portion was started at the Columbia River, near Portland (Oregon).

Work progressed steadily, the prairies were crossed as far as Bismarck, on the Missouri River, and the eastbound line from Portland reached Tacoma. Then the great financial crash of 1873 hit the United States and the railway was caught at a disadvantage. The statements circulated by Jay Cooke and Co. were subjected to considerable adverse criticism, and panic-

The five years 1870-

Winter Hardships

After the financial crisis constructional work practically ceased, but the line was kept in thorough repair and showed a steady increase in revenue. Large numbers of settlers were attracted to the country served by the railway, and cultivation was put on a firm basis. The land that had been regarded as desert proved to be wonderful wheat country; but another popular fallacy proved a stumbling-

In the early days of the Northern Pacific Railway, however, it was deemed advisable to run before the storm, rather than to stand and endure the rigours of the winter. United States troops, holding in check the remaining Indians on the prairie, increased the fears of the settlers with highly-

The general belief that the winter-

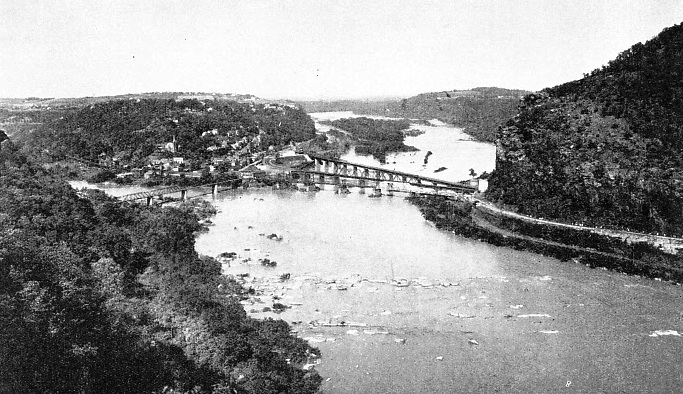

RAILWAY BRIDGES at Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia. Harper’s Ferry is the meeting point of three states, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia, and of two rivers, the Potomac and Shenandoah. The locality is served by the lines of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

The railway’s policy met with a dramatic reversal in 1876, when the settlers were faced with a peril greater than that of the winter storms. This was the rebellion of the Sioux Indians. The United States Government decided on drastic military action, with Bismarck, on the banks of the Missouri, as the base. To ensure the necessary supplies, the railway company was induced to keep the line open during the winter of 1876-

In 1879 the railway’s financial position had improved and construction was resumed. On the eastern section of the line the track had to be carried over the Mississippi, necessitating the construction of a great bridge. This immense structure, 1,400 ft long, is divided into three spans with the railway track carried 50 ft above the water, and cost £200,000.

After crossing the river, construction became easier, and the building of the railway proceeded apace across the plains of Dakota and Montana as far as the foothills of the Rocky Mountains.

On the western section work was necessarily carried on at a slower pace, as the range of the Cascade Mountains constit-

Two tunnels also were necessary through the range of the Rocky Mountains, the Bozemann Tunnel, 3,160 ft. long, and the Mullan Tunnel, with a length of 3,847 ft. Simultaneously with the construction of the main line from the eastern and western ends respectively, short branches were laid in promising districts for mining, lumbering, and agricultural development.

Subsidized Railroads

Control of the Northern Pacific Railway was at that time in the hands of Henry Villard, one of the most remarkable characters in the history of the United States of America.

Villard was born at Speyer, Germany, in 1835, and was the son of a Bavarian judge. In 1853 he went to America, where he learned English and became a journalist. He was a war correspondent during the Civil War. After many years of newspaper work, both in Europe and America, Villard turned his attention to railway finance and organization. He became President of the Northern Pacific Company in 1881, and immediately directed his energies to speeding the completion of the northern transcontinental route. On September 8, 1883. the eastern and western branches of the railway met at Gold Creek, in Hellgate Canyon, Montana, thus bringing into operation some 2,260 miles of line.

One of the most important works undertaken during the construction of the Northern Pacific was the Stampede Tunnel through the Cascade Mountains.

To-

One of the earliest railways to be built in the interior of the United States was the Illinois Central Railroad, which was formed in February, 1851, by the General Assembly of Illinois. Two and a half million acres of public land had been granted to the State by Congress in 1850 for the construction of a railroad from the southern terminus of the Illinois and Michigan Canal to a point near the junction of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, with a branch to Chicago and another to Dubuque, near the state of Iowa. The Illinois Central was, therefore, the first of the land grant railroads, and the system was subsequently adopted by other lines, notably the Union and Central Pacific Companies.

The Illinois Central now operates over 6,850 miles of track, of which 155 miles have been electrified. There are over 1,750 locomotives, nearly 1,900 passenger cars, and about 62,500 freight cars.

A MODERN EXPRESS on the Illinois Central System. This picture shows the “Louisiana”, a daily train between Chicago and New Orleans. The system handles some 1,750 locomotives, 1,860 coaches, and 62,500 freight wagons.

[From part 48 and part 49, published 27 December 1935 and 3 January 1936]

[Read the previous article in part 48] [Read the next article in part 49]

You can read more on “The Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe Railway”, “Giant American Locomotives”, “The Pennsylvania Railroad”, “Speed Trains of North America” and “The Union Pacific Railway” on this website.