© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

Railways at War - 1

Railways at War During the Nineteenth Century

“Commencement of the railway works at Balaclava”, from the Illustrated London News of March 10, 1855.

THE PRESENCE of the Duke of Wellington at the opening of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway in 1830 might well mislead one into thinking that the British, the first to make railways a practicable proposition, were also swift to see their military potential, for the speed and reliability which railways could offer obviously revolutionised man’s mastery of time and space, the fundamental dimensions of strategic thinking. In fact the “Iron Duke” was present in his civilian capacity as Prime Minister. Nevertheless in 1834 the promoters of the projected London & Southampton Railway did think it worthwhile to bring before Parliament as witnesses to support their cause Admiral Sir Thomas Hardy, General Sir Willoughby Gordon and five captains of the Royal Navy, to testify to the military value of a railway link between the capital and its major Channel ports.

The authorities were also quick to see the value of railways as a means of transporting police and troops to put down demonstrations and riots in various parts of the country. At the height of the Chartist agitation in 1842 a Railway Regulation Act was passed by Parliament requiring railway companies to carry troops, but only “at the usual hours of starting”. This was later amended to include the possibility of running “specials”, but, whatever the arrangements, all military passengers were to be scrupulously paid for at the full rate. Apart from using railways as an aid to maintaining law and order or as a link in the chain of transport to overseas stations, the military establishment remained indifferent to their strategic potential for more than two decades after their inception. The Admiralty merely concerned itself with ensuring that structures such as the Saltash Bridge over the Tamar or the Britannia Bridge over the Menai Strait should not obstruct shipping.

The real vindication of the railway came during the Crimean War of 1854-

The answer was, of course, a railway and it was sent out from England by that titan among engineers, Thomas Brassey, at his own expense. It arrived complete with wagons and a small army of navvies and was in operation by March 1855, despite the fact that most of the rolling stock had to be rebuilt before it could be used. At first the trains were horse drawn, with a stationary engine to help the horses manage one steep gradient, but later small locomotives were sent out. Another distinguished engineer, I. K. Brunel, also lent his talents to the war effort, designing a prefabricated hospital which has remained the basic model for all such field medical units in subsequent wars.

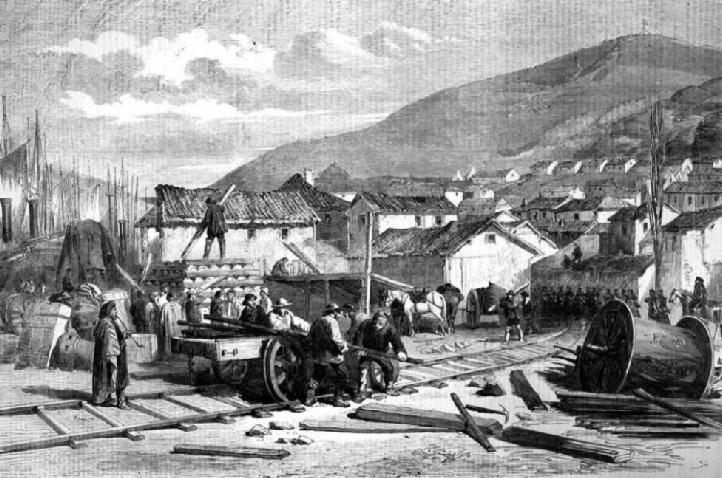

A railborne gun battery built for the American Federal Government in 1861 by the Baldwin Company. It was proposed to carry 50 riflemen and a rifled cannon capable of bearing through the end or side ports.

By bringing supplies up to the front line and evacuating the wounded on the return trip, the Balaclava railway made possible the final assault on Sebastopol which brought the futile war to a close. The experience had taught some useful lessons -

Unfortunately it seems to have been necessary to re-

The Mutiny of 1857, which revealed the precariousness of Britain’s hold over India, led to the construction of strategic railway lines throughout the sub-

In Europe, meanwhile, the French were giving the first convincing display of the strategic, rather than the merely tactical, use of railways. Having provoked Austria into declaring war in 1859, France sent to the aid of her ally, Piedmont, 76,000 men and 4,450 horses, who made the journey from Paris to northern Italy in 10 days. The supply arrangements, however, failed to match the efficiency achieved in the initial deployment and, after the bloody battles of Magenta and Solferino, the French were unable to pursue the beaten Austrians beyond the Mincio for lack of food, despite the fact that they had a fully operational railway network at their rear. This was more than could be said of the Austrians whose incomplete system of single-

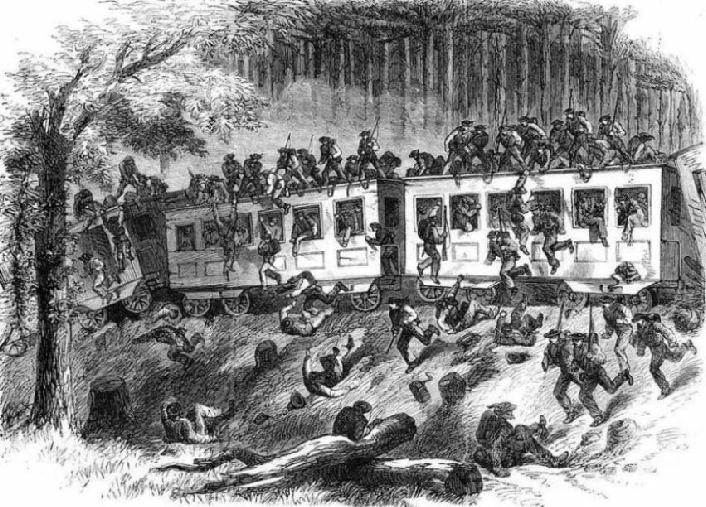

Despite the shortcomings on both sides, the spectacle of French military success revived old fears of Napoleonic ambitions in Britain. Volunteer rifle companies were formed in large numbers in 1859 and 1860 and there was talk of constructing a circular railway around London to carry armoured trains. In 1862 tension was still sufficiently high for the War Office to veto a proposed broad-

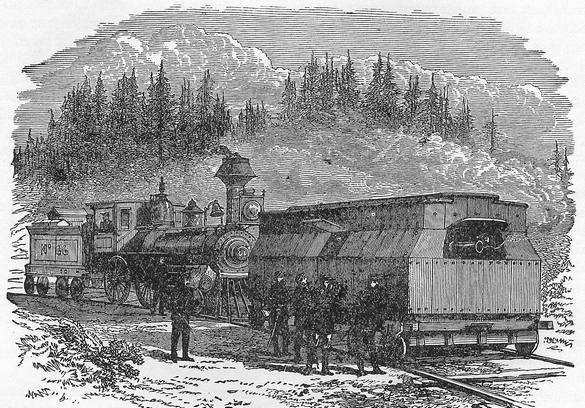

An artist’s impression of a train with American Civil war reinforcements running off the track in 1863.

The American Civil War

The real lessons of railway warfare were, however, to be learned, not from Europe, but in North America. On the eve of the American Civil War, Colonel R. Delafield had presented to Congress a report on the state of the art of war in Europe, a report in which he had placed particular emphasis on the military potential of the railway. Despite that, both the Federal and the Confederate armies were slow to organise the railway systems at their disposal, although the field of conflict they were to contest was as large as the whole continent of Europe. Indeed, the Confederates delayed until February 1865, the last year of the war, before imposing state control in a futile effort to undo the damage inflicted by suicidal competition between the various southern railway companies. The victory of the North was largely determined by the efforts of two men -

Thanks to McCallum and Haupt a rapid programme of railway building was pushed ahead and such novelties as railway corps, armoured trains and hospital trains introduced. Prodigious feats of transportation became almost commonplace. In September 1863, 23,000 men with their artillery and horses were moved 1,200 miles in seven days to save Rosecrans after his mauling at Chickamauga, a deployment which, without the railway, would have taken about three months. Sherman’s decisive campaign through the South, starting from the vital junction at Chattanooga and ending with the destruction of the railway town of Atlanta and the terrible march through Georgia, was made possible by a single line of track which the Confederates never managed to cut for more than a few days at a time. The effect of this manoeuvre was to sever the railway connections between Robert E Lee’s army in Virginia and his supply base in the South and thus oblige him to surrender.

The American Civil War also produced an epic of individual endeavour which has never been paralleled in the history of railways. On April 12, 1862, a band of 21 Federal soldiers, led by Captain James J. Andrews and disguised as civilians, stole the locomotive General and a number of carriages of a north-

It is tempting to speculate on whether or not the railways made the Northern victory inevitable and thus secured the preservation of the Federal Union. Had it not been possible to reach a temporary compromise over the slavery issue in 1850 and had the South seceded in that year it is doubtful whether the North, with its few disconnected lines, could ever have mounted the massive probing counter-

The “War Between the States” naturally attracted its share of European military observers; among them Moltke, the Prussian genius, dismissed the mighty struggle contemptuously as that of “two armed mobs chasing each other around the country, from which nothing could be learned”. The evidence suggests, however, that Moltke learned a great deal. As a young man in the early 1840s he had risked his savings in the new Hamburg-

In fact the Prussians were building on a long-

The Effect of Other Wars in Europe

In 1847 a German military writer asserted that transport of artillery and cavalry by train was impossible and denied that any railway could carry 10,000 men over 60 miles within 24 hours. The Austrian mobilisation along the Silesian frontier in

1850 seemed to prove his point, as 75,000 men and 8,000 horses took 26 days to travel the 150 miles from Vienna. As opponents of the railway were swift to point out, they could have done it faster on foot. Nevertheless the Prussian General Staff had already gained enough faith in the new mode of transport to begin compiling a comparative survey of railways from the military point of view and the Austrians, having digested the lessons of the debacle of 1850 -

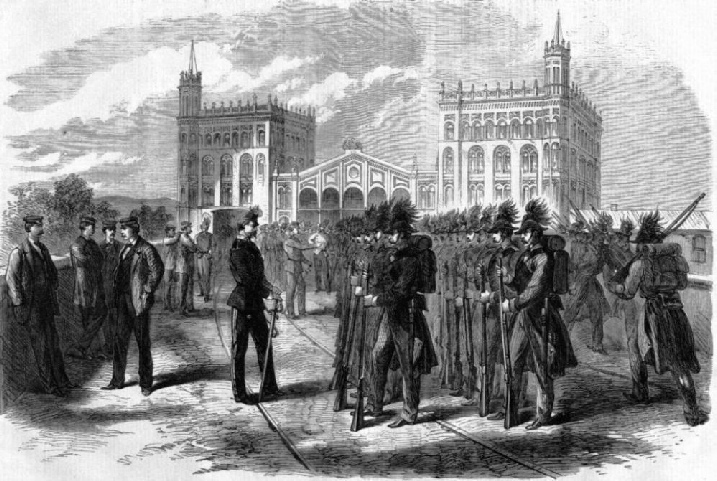

Austrian soldiers mustering at the Northern Railway Station, Vienna, in 1866.

When Prussia and Austria finally clashed in 1866 it was the railway which proved decisive. Using five lines to Austria’s one, Prussia was able to compensate for her late mobilisation and deploy a screen of 250,000 troops over a front of about 270 miles, enabling her generals to bring the Austrians to a quick defeat at Sadowa. This “Six Weeks War” was, indeed, so rapid that its lessons were largely lost on contemporaries. In retrospect, however, it is possible to see how the railways meshed in with other technical developments of the period. Without them it would have been impossible to keep the front line supplied with the quantities of ammunition required for the quick-

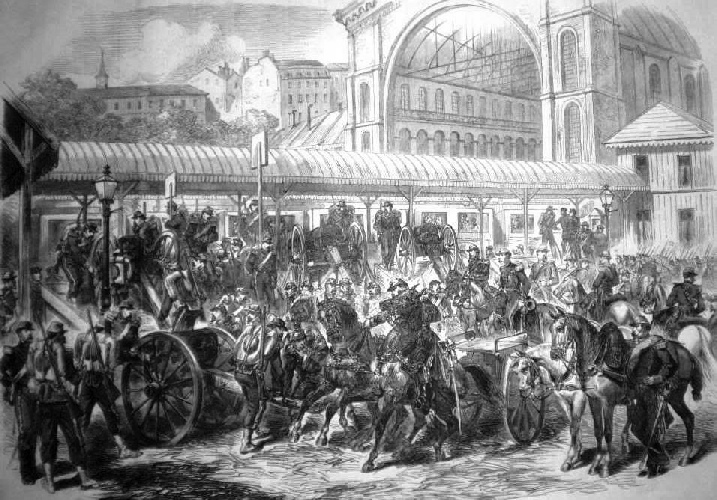

The Franco-

Again it is difficult to resist the speculation that if the confusion had been that little bit worse, if the Est Company had disintegrated into total chaos, then the French army would not have been thrown into action so rashly and could have taken advantage of Prussian supply shortages to attack the invaders as they began to lose momentum. Thus might the Second Empire have been saved instead of lost. As it was the French were defeated on the frontiers and the Prussians were able to use the railways to bring up enough food and ammunition to besiege Paris and bombard it into submission, to the astonishment of all Europe. As a result of the Franco-

A Mitrailleuse battery dispatched from Paris by the Strasbourg Railway in 1870.

Another result was strategic railway-

A similar idea lay behind the scheme for a Berlin-

The roots of the 1914-

But once mobilisation had begun the railway timetable took over. Nothing could be altered for the first five days without causing the whole system to collapse into complete anarchy. Thus the feverish last-

Details guarding the line: Russian vigilance on the Trans-

You can read more on “The Railway in War”, “Railways at War 2” and “The Trans-