Railways During the World Wars

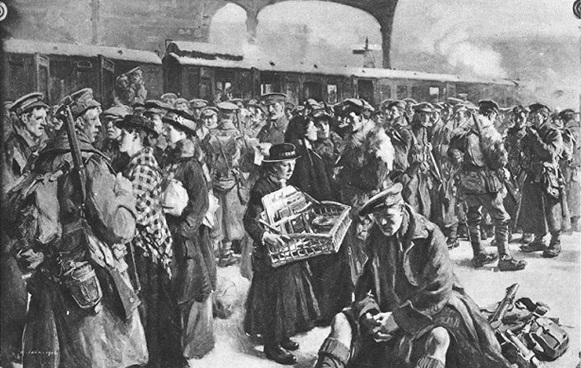

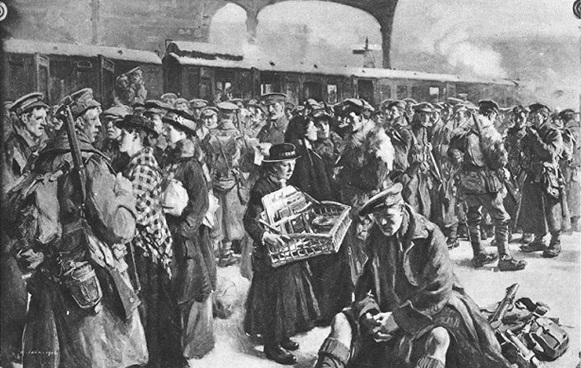

“The Return from the Front: Victoria Railway Station” by Richard Jack, ARA.

THE Great War of 1914-18 marked a turning point in the history of Britain’s railways, as in so many of her institutions. The pride and self-assurance of the Edwardian era were never to be recaptured. In 1914 the Regulation of Forces Act, passed in 1871 in the shadow of Prussia’s railway-borne victory over France (see the chapter “Railways at War - 1”), put the railways of Britain under state control for the first time in their history. Henceforth they were to be operated as a single unified system under the direction of a Railway Executive Committee presided over by the President of the Board of Trade. But it was still far from nationalisation. The membership of the Railway Executive Committee was entirely composed of the general managers of the eleven largest railway companies and the companies were guaranteed the same profits as they had made in 1913, a year which, incidentally, had been rather prosperous. Thus the system of state control which was adopted was one in which railways were run for the government but not by the government.

The wartime tasks imposed on the British railway system were immense. The flow of traffic was greatly intensified at the very time that 30 per cent of the railway labour force was recruited into the army and the diversion of railway manufacturing capacity to munitions production made it almost impossible to obtain new rolling stock. Maintenance and investment were seriously neglected, with significant consequences in the post-war period. In retrospect this seems an incredibly short-sighted policy; but, given the task to hand, it was probably inevitable.

To grasp the overall picture is difficult and a more accurate impression may be gained by looking at the work of one or two vital lines. Consider, for example, the strains imposed on the London & South Western Railway, the main supply-route for British forces on the Continent, or on the Highland Railway, which performed the same function for Scapa Flow and Cromarty Firth, two of the Grand Fleet’s most important bases. Admittedly the London & South Western, which served Aldershot and Salisbury plain, had long military experience to fall back on, but it had never before faced the problem of funnelling literally millions of men, converging along five main routes, into the single port of Southampton, which was the main point of embarkation for the Western Front. More than 20,000,000 soldiers were transported by the London & South Western in the course of the war, an average of 13,000 every day.

No less remarkable was the achievement of the Highland Railway, for it was peculiarly ill-adapted to the needs of war. Before 1914 heavy traffic on the line had been confined to a three-month summer tourist season; three-quarters of its length was only single track and there were few sidings or loops. Within a year a third of its locomotives were to be out of service and another third badly in need of repair; but still the line somehow kept the traffic flowing and remained a vital, if tenuous, link in a chain of communication which maintained the naval shield on which Britain's national security depended.

In the autumn of 1914 the generals, and the public, had anticipated a “war of movement” which would be “over by Christmas”. It was expected that the pattern of the Franco-Prussian war would be repeated - a massive deployment of troops by railway followed by a single, bloody and decisive battle on the frontiers. The stabilisation of more than a hundred miles of trench fortifications created a novel situation in which railways were to play a new role as the need to supply forward positions and, later, to stockpile ammunition and stores for major offensives, led to the extemporisation of a tactical railway network behind the lines. Communications problems, revealed starkly during the Somme offensive of 1916, led to an official decision to set up an organised system of light railways, which was rapidly extended in 1917 and 1918; from the main system trench tramways, utilising men and horses for motive power, proliferated as feeder lines. By the end of hostilities the army’s Railway Operating Division had a total strength of 18,400 men organised in 67 companies. In all 76,000 troops and 48,000 men in labour service units were employed in running and safeguarding this largely new network of 800-odd miles, a network which necessarily came to bulk large in Allied strategic thinking.

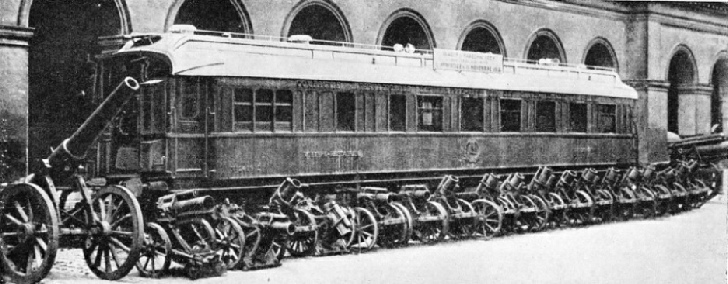

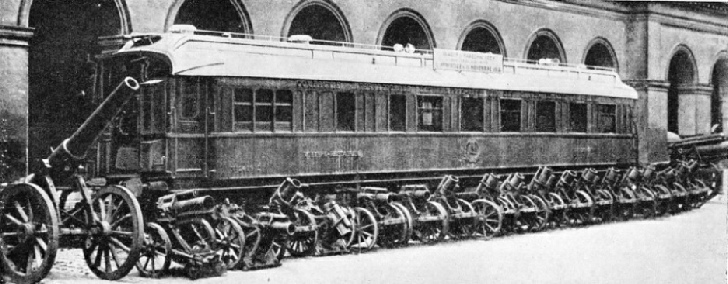

Coach number 2419 in which the Armistice which concluded the war of 1914-18 was signed. It was subsequently preserved by the French at Rethondes, near Compiegne.

According to the official war history the decision of Marshal Foch, the supreme coordinator of the Allied counter-offensive of 1918, to grant the Germans an armistice, was largely determined by the realisation that the Allied advance was about to run out of reach of its railheads. If it had not been so, of course, Hitler and his followers would never have been able to argue so powerfully that the German army had never been defeated nor the homeland invaded. In view of the strategic and tactical importance of railways in that war, it was perhaps rather appropriate that the armistice which brought it to a close should have been signed in a railway carriage - which Hitler was to insist on using again to accept the surrender of France in 1940.

Railways were, of course, important in other theatres of war, and especially in the Middle East, where Colonel T. E. Lawrence’s train-wrecking activities played a large part in disrupting the defence of the Ottoman Empire. In Salonika and East Africa, railway units also played their part in ensuring Allied victory, while, on the other side, German railwaymen struggled to maintain a vast network, stretching from the Baltic to the Bosphorous. In Russia the total collapse of the railway system, resulting in the cessation of supplies to the front or of food to the towns, was a major factor in precipitating the outbreak of revolution. In Britain the situation was by no means so dramatic, but it was acute enough for the Liberal-Conservative government of the day to entertain a solution which in many circles would be branded as revolutionary, and even Bolshevik, in its inspiration nationalisation.

State control of Britain’s railways, which had been debated and dismissed as far back as the 1840s, had now been vindicated by the test of war. It had not only enabled the railways to meet the extraordinary demands made upon them, it had also enabled them to achieve a number of striking economies in operation through such schemes as the pooling of wagons or arrangements to eliminate unnecessary haulage of coal. The coal distribution rationalisation alone saved 700 million ton-miles a year after its introduction in 1917. As early as 1915 the Trades Union Council had passed a resolution calling upon the Government “before relinquishing its present control to introduce legislation having for its object the effecting of complete national ownership of the railways.”

Sir Herbert Walker, general manager of the London and South Western and de facto head of the Railway Executive stated publicly that he did not “think that our railways will ever again revert to the independent and foolish competitive system” of the pre-war period. Lloyd George himself intimated that nationalisation was seriously being considered by the government and, in December 1918, Churchill actually asserted that that was in fact the government’s policy.

No. 1718, a Railway Operating Division 2-8-0 locomotive. This design was the standard heavy freight locomotive operated in Europe by the ROD during the First World War.

In 1919 a Bill was introduced to establish a Ministry of Ways and Communications with powers of compulsory purchase which would enable the state to acquire railways, docks and canals by Order in Council. But the times were not propitious for such a momentous step, despite the success of the wartime experiment. The spectre of Bolshevism was abroad; there was a general resentment against the continuation in time of peace of war controls and a desire to “get back to normal” which swept away the whole apparatus of state control of industry, agriculture, finance and transport which had been constructed piecemeal in the course of the war. By the time the Bill emerged from Parliament the purchase clauses had been cut away and the proposed all-embracing Ministry of Ways and Communications reduced to a mere Ministry of Transport. Nationalisation was finally rejected in the summer of 1920 in favour of a compromise measure of rationalisation which was embodied in the Railways Act of 1921.

The 1921 Act was to play a major part in determining the future development of the railways. The 120 companies of the pre-war era were reduced to four main groups - the London & North Eastern, the London, Midland & Scottish, the Great Western and the Southern. The reorganisation would, it was hoped, enable the railways to achieve new economies of scale in operation. The public interest would be protected by a Railway Rates Tribunal and an elaborate system of conciliation procedures designed to prevent stoppages like the national railway strike of 1919. Some competition would remain along the “frontiers”, and cities like Exeter, Leeds, Sheffield and Glasgow would be served by more than one group but, on the other hand, major industrial areas like South Wales and Lancashire would thenceforth depend entirely on the services of a single railway organisation.

Unfortunately the amalgamation scheme, though it looked like a step towards greater efficiency, had been determined largely by political pressures and according to political principles. The economic aspects of the problem had been pretty well ignored or were assumed to require no detailed examination. There was, therefore, no study made of the optimum or viable size for a railway unit and the maintenance of the shibboleth of private ownership, which blocked the dismantling of former companies, led to the creation of four groups which were extremely unequal in their size and capacities. The London & North Eastern, for instance, struggled with an unhappy legacy of uneconomic country branch lines and was to find itself dependent for most of its custom on a Tyneside plunged in the depths of industrial depression. The Southern, which had borne the brunt of the strain imposed by war, found itself faced with the need to accommodate a massive and expanding commuter belt around London. Thanks to the energy and vision of the indefatigable Sir Herbert Walker it found its salvation in a programme of electrification which brought Portsmouth, Brighton and Chatham virtually into London’s backyard.

The 1921 Railways Act imposed on the railway companies a new outlook which required great organisational and psychological readjustments, while regrettably maintaining a tradition of Parliamentary regulation that hamstrung the railways when they attempted to meet the challenge of motor transport, which had developed rapidly as a result of the war. Large-scale production of military vehicles, plus the protectionist McKenna duties, imposed in 1915 to economise on shipping space by limiting the importation of luxury goods like French and American cars, had created the facility in Britain to turn out large quantities of buses, lorries and cars. With their permanent way maintained at the expense of the taxpayer and with no statutory obligation to provide “reasonable services” or to publish their freight rates, the road hauliers and bus companies were all set to cream off the profits of the best routes, leaving the railways to make what they could from such stricken customers as the coal and steel industries. Little wonder that by 1938 the railways were clamouring for a “square deal”.

The 1921 Railways Act imposed on the railway companies a new outlook which required great organisational and psychological readjustments, while regrettably maintaining a tradition of Parliamentary regulation that hamstrung the railways when they attempted to meet the challenge of motor transport, which had developed rapidly as a result of the war. Large-scale production of military vehicles, plus the protectionist McKenna duties, imposed in 1915 to economise on shipping space by limiting the importation of luxury goods like French and American cars, had created the facility in Britain to turn out large quantities of buses, lorries and cars. With their permanent way maintained at the expense of the taxpayer and with no statutory obligation to provide “reasonable services” or to publish their freight rates, the road hauliers and bus companies were all set to cream off the profits of the best routes, leaving the railways to make what they could from such stricken customers as the coal and steel industries. Little wonder that by 1938 the railways were clamouring for a “square deal”.

War poster published on behalf of the four main-line companies by Reginald Mayes.

The outbreak of war in 1939 precluded any possibility of salvaging the lost fortunes of the railways and once again imposed upon them the massive strains of total war. In an age of air and motor transport and after nearly a quarter century of under - investment, the railways were still called upon to shoulder the major part of the burden. Not only did they have to cope with a vastly expanded volume of regular traffic, they also had to hold themselves ready to adapt the whole system to meet a national emergency at a moment’s notice. The most spectacular exercise of the emergency machinery was, of course, Operation Dynamo, which was set in motion on May 26, 1940, to assist the evacuation of the troops from Dunkirk. The main problem was to get the men away from the South Coast ports to reception centres far inland as quickly as possible. Two thousand railway coaches were immediately pooled for the purpose and Redhill junction closed to act as a clearing house. There was no time to organise a timetable and all train movement orders were therefore issued minute by minute over the telephone. Thanks to the skill of the railwaymen and the enthusiasm of thousands of volunteers, all of whom put in incredibly long hours, about 320,000 men aboard 620 trains were ferried away from the danger areas in a single hectic week.

Bombing was, of course, a new hazard to be overcome. It was particularly severe in the summer and autumn of 1940, when more than half of all the stoppages and delays caused by aerial action occurred, and again during the V2 attacks of 1944. The most concentrated damage was inflicted by saturation raids on dock areas, but direct hits on bridges also caused long delays and throughout the war unprotected trains seem to have been a temptation which few lone raiders could resist.

A4 Pacific “Sir Ralph Wedgwood” badly damaged by a German bomb at York locomotive depot in 1942.

Stations suffered mixed fortunes. Dover naturally received considerable punishment while, far away, Middlesbrough was smashed by a stick of bombs. In London, St Pancras was badly damaged and nearby King’s Cross had part of Cubitt’s famous roof blown away. Locomotives seem to have been remarkably tough; of the 484 which were hit only eight were a total write-off. Three thousand or so wagons and carriages were destroyed. Doubtless many more were casualties of marshalling in blackout conditions. Total damage has been estimated at £30,000,000, a figure which pales into insignificance beside the estimated £200,000,000-worth of arrears of maintenance.

Total war meant a total mobilisation of national resources and the mobilisation of the whole population. It meant diverting more than 100 locomotives, converted at Swindon from steam to diesel, to distant Persia to serve the Allied lifeline to Russia. It meant an LNER driver and fireman earning a George Cross apiece for driving an exploding ammunition train out of Soham station into open country. It meant shuttling 100,000 men through Southampton in the six days after D-day. Total war involving such extraordinary disruptions left Britain’s railways in a disastrous state. Nationalisation became, therefore, not so much a political objective to be achieved as a vital prerequisite for post-war economic recovery.

Twice in the twentieth century Britain’s railways have been called upon to make heroic efforts and great sacrifices in the nation’s defence. Many of their problems have been the direct result of the loyalty and devotion with which the call of duty was answered. An honoured place in Britain’s transport system is the only fitting epitaph for such a record.

Stanier 8F 2-8-0s were extensively used by the War Department for military service overseas during the Second World War.

Stanier 8F 2-8-0s were extensively used by the War Department for military service overseas during the Second World War.

You can read more on “The Railway in War”, “Railways at War 1” and “The Trans-Caspian Railway” on this website.

The 1921 Railways Act imposed on the railway companies a new outlook which required great organisational and psychological readjustments, while regrettably maintaining a tradition of Parliamentary regulation that hamstrung the railways when they attempted to meet the challenge of motor transport, which had developed rapidly as a result of the war. Large-

The 1921 Railways Act imposed on the railway companies a new outlook which required great organisational and psychological readjustments, while regrettably maintaining a tradition of Parliamentary regulation that hamstrung the railways when they attempted to meet the challenge of motor transport, which had developed rapidly as a result of the war. Large-

Stanier 8F 2-

Stanier 8F 2-