© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The Romance of the LNER

From the World’s First Steam Railway to the “Flying Scotsman”

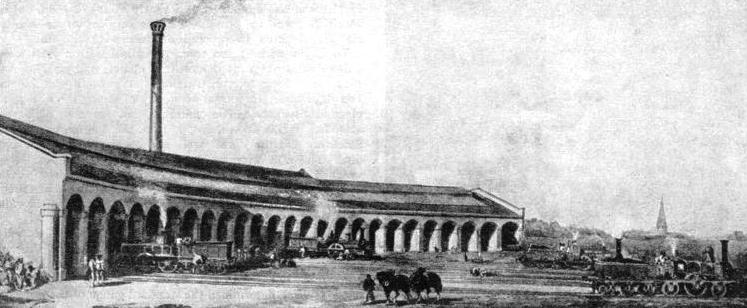

A REMARKABLE ILLUSTRATION of the original locomotive shed at King’s Cross Station, formerly a terminus of the Great Northern Railway.

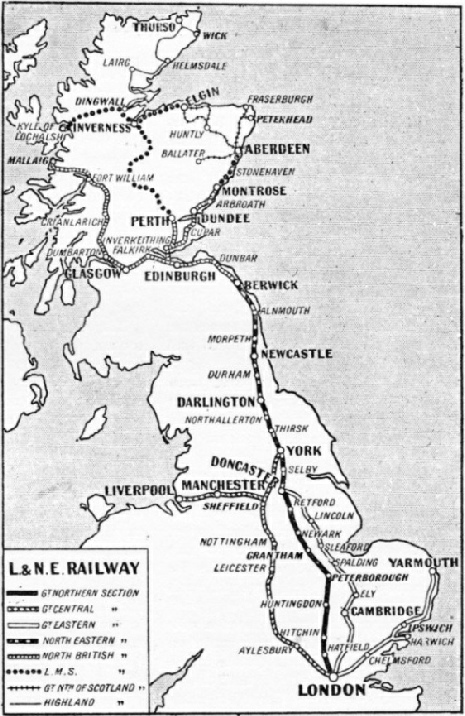

THE London and North Eastern Railway, which incorporates the former Great Central, Great Eastern, Great Northern, Hull and Barnsley, North Eastern, North British and Great North of Scotland Railway Companies, is the second largest railway company in Great Britain. With a total single track mileage, including sidings, of 16,824, the system covers the whole of Eastern England and East and West Scotland. It serves the country between the Moray Firth and the Thames.

The LNER claims to have been started by George Stephenson when he constructed the first steam railway in the world, between Stockton and Darlington.

The North of England has many memorable associations, and not the least, among them are the incidents connected with the introduction of the railway system. It was in this territory that the old wagon-

The first public suggestion of a railway in South Durham was made on September 18, 1810, at a dinner in the Town Hall, at Stockton, held under the auspices of the Tees Navigation Company, to celebrate the opening of the “New Cut” a short canal 210 yards in length; and the suggestion was in the form of a resolution moved by Leonard Raisbeck, the Recorder of Stockton, and seconded by Benjamin Flounders, of Yarm, that a committee should be appointed to “inquire into the practicability and advantage of a railway or canal from Stockton by Darlington and Winston, for the more easy and expeditious carriage of coals, lead, etc.”

The committee was appointed, and took a year to consider the proposal, finally recommending that either “canal or railway would not only be productive of considerable advantage to the country in general, but would likewise afford an ample return to the subscribers”.

At a meeting held at the King’s Head Hotel, Darlington, on January 17, 1812, it was decided that the services of the eminent engineer John Rennie should be secured; but it was not until the following year that Rennie spent a week in examining the country between Stockton and the Auckland coalfield. His opinion was in favour of a canal 16 ft wide at the bottom, 31 ft wide at the top, and 4½ ft deep, which he calculated would cost £205,618.

This estimated cost was prohibitive, as it was submitted when Great Britain was at war with France and the United States, and money was scarce. It was not until after the Treaty of Paris and the Peace of Ghent that any further action was taken. On February 7, 1815, the subscribers to the survey were called together, without, however, anything definite resulting from their meeting.

“THE RAILWAY KING” George Hudson, a great financier of the nineteenth century, whose story is linked with that of the LNER. He spent £3,000 a day in legal fees when fighting rival companies.

The project remained dormant while those in favour of a canal proposed more waterways, and a new survey of the district recommended a line of canal considerably to the north of the route planned by Rennie. This proposal for a Stockton and Auckland canal made the people of Darlington, which town was ignored, uneasy. It was necessary for Darlington and Yarm to do something, and the original canal and railway scheme was revived. A Welsh engineer, George Overton, who had experience of tramways, was employed to survey and report upon a canal or railway. He estimated that a railway would cost £124,000 for fifty-

Then George Stephenson formed his alliance with Edward Pease. They met on the day on which royal assent was given to the first Stockton and Darlington Railway Act, the Bill for which had had a rather stormy passage through Parliament, owing to the opposition of landowners. A further survey of the route for the tramway or railway was suggested by Pease, and George Stephenson, assisted by his son, Robert, who was then just eighteen years of age, proceeded with this work.

Several deviations were suggested by the engineer, with a shortening of the distance. Although steam locomotives were not provided for, Stephenson wrote to a friend, “We fully expect to get the engines introduced on the Darlington railway”. On January 22, 1822, the shareholders of the Stockton and Darlington Railway met for the purpose of electing the engineer. At this meeting, which was held in the company’s office at High Row, Darlington, George Stephenson was appointed at a yearly salary of £660, out of which he was to provide for the services of assistants. He was directed to proceed at once with the line.

Several deviations were suggested by the engineer, with a shortening of the distance. Although steam locomotives were not provided for, Stephenson wrote to a friend, “We fully expect to get the engines introduced on the Darlington railway”. On January 22, 1822, the shareholders of the Stockton and Darlington Railway met for the purpose of electing the engineer. At this meeting, which was held in the company’s office at High Row, Darlington, George Stephenson was appointed at a yearly salary of £660, out of which he was to provide for the services of assistants. He was directed to proceed at once with the line.

CONTROLLING 16,824 MILES of track, the LNER main line systems are founded on those of earlier companies, as shown.

To begin with, 1,200 tons of malleable iron rails were ordered, and 306 tons of cast-

But more was accomplished than was realized. Not only was this the beginning of the first railway in the world, but also Mr. Meynell, by placing the first rails 4 ft 8-

Construction was rapid. In applying to Parliament to carry out the deviations suggested by Stephenson, a clause was passed allowing the railway to “make and erect such and so many locomotive or movable engines as the said company of proprietors or any person or persons authorised by them . . . shall from time to time think proper and expedient, and to use and employ the same in or upon the said railways or tram-

The hour of the steam locomotive had arrived. The Company decided to instruct George Stephenson to make two locomotive engines at a price of £500 each.

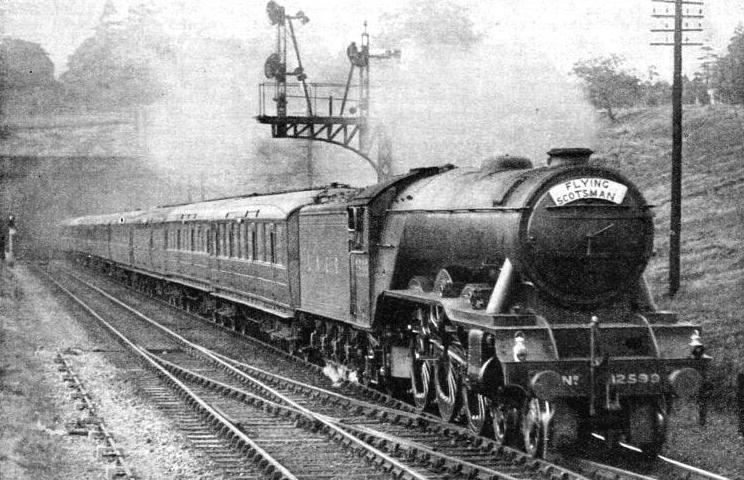

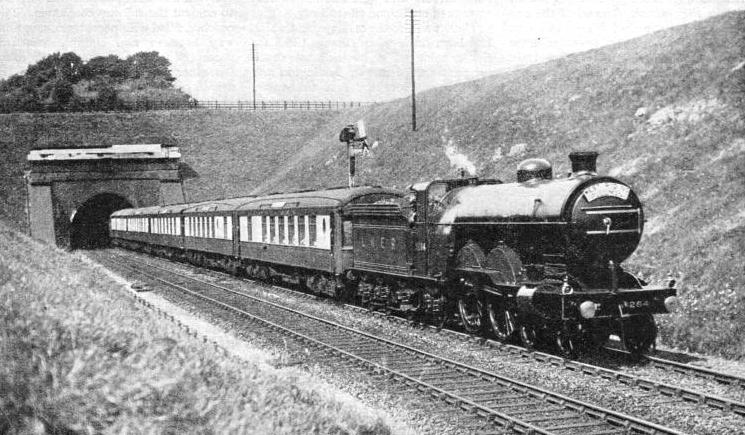

A CLEAR ROAD. An impression of the “Flying Scotsman” -

Schemes for further railways were, by this time, very much in the air. Lines to connect Liverpool with Manchester, and to link Birmingham, Derby, Nottingham, Hull and Manchester, and to connect with London, were talked about. William Bell, of Edinburgh, suggested to the Mayor of Newcastle-

The First Passengers

On September 27, 1825, the Stockton and Darlington line, to the extent of twenty-

Towards the evening of September 26 the engine “Locomotion” was attached to the carriage at Shildon, and a select company made a trial trip to Darlington, the engine being driven by James Stephenson. George Stephenson’s elder brother. This was the first occasion on which a locomotive engine had drawn a carriage constructed for the conveyance of passengers on a public railway.

With great confidence the promoters of the new railway had announced that the line would be opened on Tuesday, September 27, and as early as half-

At Shildon Lane End, the new locomotive, “Locomotion”, stood in a bright coat of fresh paint, getting up steam for the most spectacular part of the opening, the run to Darlington and Stockton. Alongside was the single carriage, the “Experiment”. Some time elapsed before the train was coupled up. The accommodation provided for no fewer than 300 passengers, sixteen or eighteen in the carriage, and twelve to thirteen in each wagon.

Tickets of invitation had been issued, but there was a rush for the seats, and 450 people -

The locomotive engine, driven by George Stephenson. Tender with water and coals. Six wagons loaded with coals; passengers on the top of them. One wagon loaded with sacks of flour; passengers among them. One wagon of surveyors and engineers. Coach occupied by the directors and proprietors. Six wagons filled with strangers. Fourteen wagons packed with workmen and others. Six wagons loaded with coals; passengers on the top of them.

THE FISH DOCKS AT GRIMSBY, an important port served by the LNER. The railway runs alongside the docks, and “catches” of fish can be loaded direct on to the train. The port was formerly served by the Great Northern and Great Central Railways.

The gradients for some distance from the start were favourable, descending at 1 in 144 for a mile and 1 in 128 for the next mile and a half. The sturdy locomotive having two vertical cylinders, with a diameter of 9½-

15 Miles an Hour

Unfortunately the wagon of surveyors and engineers left the rails owing to one of the wheels not having been properly set on the axle, and the train was stopped. The wagon was replaced on the rails, but it slipped off again shortly afterwards and was shunted into a siding and left behind. Farther on another stoppage occurred owing to oakum having got into the feed-

Soon afterwards the junction of the Darlington branch with the main line was reached, the first eight and a half miles having been covered in sixty-

Six wagons of coal were detached from the train and run to the depots, to be distributed to the poor. In their place two wagons were attached to the train containing the Yarm Band, and soon after twelve o’clock “Locomotion”, its boiler replenished, started off again with 550 passengers and thirty-

For five miles the track was practically level, and the hauling capacity of the engine was sorely tried, only four miles an hour being the speed. At Goosepool a further supply of water was taken by the engine, after which the journey to Stockton was resumed without a break. A falling gradient of 1 in 104 towards the end of the run again gave a speed of fifteen miles an hour, and three hours seven minutes after leaving Darlington the train arrived at the terminus at Stockton. Here a salute, thrice repeated, was fired from the seven eighteen-

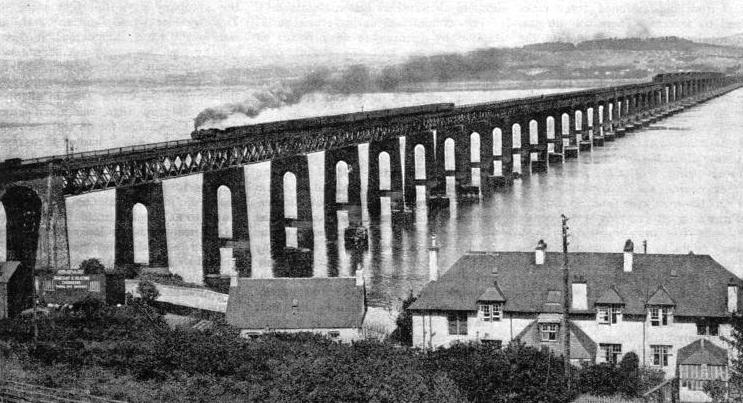

THE TAY BRIDGE, carrying the LNER across the Firth of Tay into Dundee. The first bridge collapsed in 1879. The present bridge, opened in 1887, was built a few feet to the west of the original structure, the old piers of which can be distinguished in this picture.

After such an inspiring beginning the committee of management set to work to operate the new railway, a task in which they had not the advantage of a previous example. Shortly after the opening day “Locomotion” broke a wheel, but the committee were fortunate in their first locomotive superintendent, Timothy Hackworth, the foreman of the smiths at the Wylam and Walbottle Collieries on Tyneside. Three locomotives were to be supplied by R. Stephenson and Company, of Newcastle-

There was also the arrangement which had been made with Thomas Close for the running of a horse-

Overcrowding a Century Ago

The “Experiment” rail coach was a great success, and another coach, the “Express”, was arranged to run the journey, time being reduced to about one hour and a quarter. Soon three more coaches appeared, the “Defence”, “Defiance” and the “Union”, each drawn by single horses. Six passengers were carried inside and from fifteen to twenty outside these coaches, but the numbers were often exceeded. On one occasion the “Defence” carried no fewer than forty-

Bye-

Rules of the line were made, and locomotives and trains were given precedence. Within two years the company obtained six engines: No. 1 “Locomotion”, No. 2 “Hope”, No. 3 “Black Diamond”, No. 4 “Diligence”, No. 5 “Chittaprat”, and No. 6 “Experiment”, which were stabled in a narrow barn-

From these craftsmen came the famous engine the “Royal George”, one of the Stockton and Darlington Railway’s most famous locomotives. This was the first engine built by a railway company in its own works, and by reason of its worthiness it was, in many ways, a remarkable machine.

The “Royal George” had six coupled wheels, being the first of the 0-

The committee marked their satisfaction by voting £20 as a bonus to their engineer, and the engine continued to work for twelve years, after which it was sold to a colliery in Durham for £125 more than it cost to build.

First Railway Port

During the latter half of 1829 an extension of the railway from Stockton to an obscure village known as Middlesbrough, situated near the mouth of the River Tees, was proposed. Some of the proprietors of the railway and many others were strongly opposed to this, but the town of Stockton was some distance up the winding and narrow river, and vessels of small tonnage only could be accommodated. At Middlesbrough there was deep water, and the purchase of 500 acres known as the Middlesbrough Estate was carried through, and a new port was prepared for the shipment of coals.

In January, 1829, prizes of 150 guineas and 75 guineas were offered for the best two designs for the construction of shipping staithes, and this attracted many engineers of talent.

After having investigated fifteen plans the company gave the first prize to Timothy Hackworth, and the staithes were put in hand. The extension of the railway was also begun. A suspension bridge, designed by the engineer Telford, the first railway suspension bridge, was built across the River Tees in 1830.

December 27, 1830, was a red letter day for the village, for on this occasion the engine “Globe” hauled a number of carriages and wagons, loaded with visitors and coal at Stockton, to the new port. At the staithes the coal was shipped, and some 600 people sat down to an elegant meal. The affairs of the railway never looked so promising and the Middlesbrough owners felt that their further speculation was well worth while.

Day after day the first railway engine drivers took out their engines. There was no cab for their comfort, and they perched upon narrow planks, exposed to wind, rain, heat and cold. The locomotives were without brakes, and the only way of controlling the trains downhill was to put the engines out of gear, or for the fireman to jump down and put on as many wagon brakes as he thought necessary.

A MODERN EXPRESS on the LNER line. The photograph, taken as the train was emerging from Stoke Tunnel, is of the up West Riding Pullman.

There were no gauge glasses or whistles, and a bell was fitted and tolled as a warning by tugging a piece of rope. The tail lamps were buckets of burning coke, and after dark the engine-

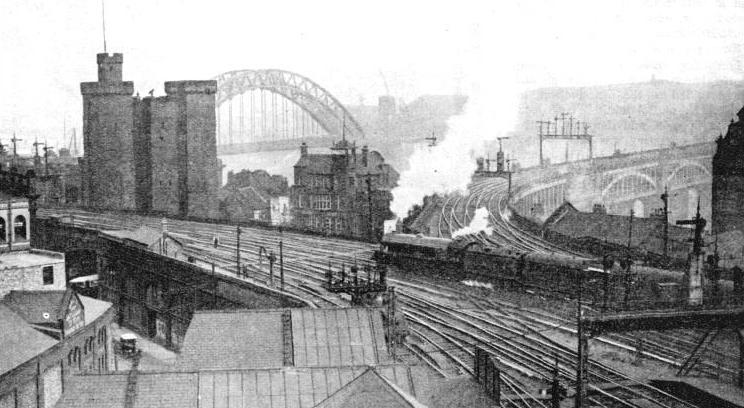

AN IMPORTANT LNER JUNCTION is that at Newcastle-

Encouraged by the example of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, other railways prepared to take part in the work of improving the means of transport. In the north of England most of the plans were from west to east, from the mineral districts towards the sea, and it was some years before projects for lines running north and south were more than matters of speculation. One of the largest of these schemes, which was carried out, was the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway, sixty-

More Extensions

From the Eden to the Tyne, and from the Tyne to the Humber, railway engineers were directing operations which were changing the face of the country, but it was not until 1854, more than twenty years later, that the North Eastern Railway was incorporated by the welding of upwards of fifty railways into a united system, forming the middle link in the East Coast route between London and Edinburgh, with a larger tonnage of mineral and coal traffic than any other system in the country, a total track mileage of 1,714, and a capital of £82,000,000.

Meanwhile, in other parts of Great Britain, other railway systems were. starting from small beginnings. Across the border in Scotland the Monkland and Kirkintilloch Railway was opened in October, 1826; with the first railway locomotives in Scotland, much after the style of “Locomotion”, other lines were built, and the North British Railway was begun in 1844 with a line between Edinburgh and Berwick. To this, the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee and West of Fife railways were added, and, in 1865, lines between Edinburgh and Glasgow, which included the first Monkland Railway. Several branches were also made during this period, and, later, the remarkable West Highland route to Fort William and Mallaig, and the Glasgow City and District, with other lines, formed the united system of the North British Railway.

The Forth and Tay Bridges, and the construction of the Waverley Station, in Edinburgh, as well as the Waverley route to Carlisle, are noteworthy features of the North British link, in the romance of the London and North Eastern Railway.

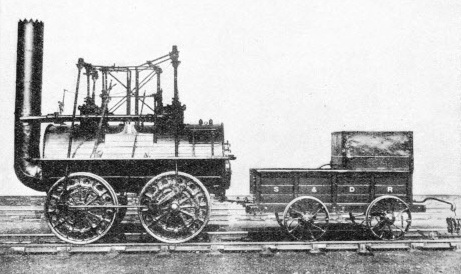

EVOLUTION (1). Three types of locomotives which have been associated with the LNER and its predecessors. This illustration shows “Locomotion No. 1.” This was built for the Stockton and Darlington Railway -

The building of Waverley Station at Edinburgh was a great task. This station covers twenty-

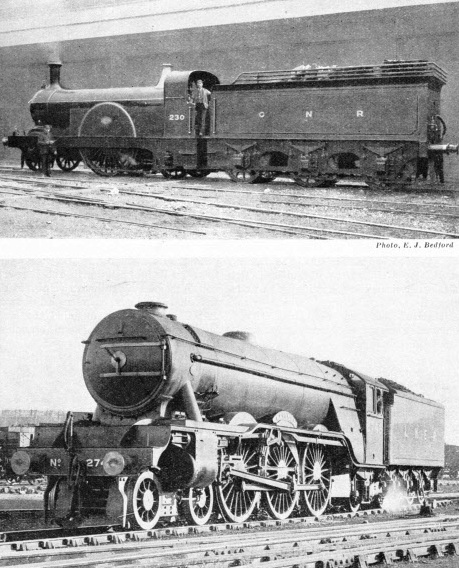

EVOLUTION (2). One of the famous 7 ft 6-

EVOLUTION (3). A modern LNER locomotive. This is a 4-

Increasing loads and the re-

Farther north, in 1846, a railway between Aberdeen and Inverness, the Great North of Scotland, was incorporated. Twenty years later this railway was consolidated by the absorption of other lines, such as the beautiful Deeside Railway from Aberdeen to Ballater, for Balmoral and Braemar. From the very first this Northern system, which had a share in the joint station at Aberdeen, introduced the electric telegraph, thus being far in advance of many other railways.

Five hundred miles farther south and some years previously, there was much railway activity in the neighbourhood of East London. The opening of a short line between London and Romford, in 1839, marked the beginning of the Eastern Counties Railway, the scheme for which received royal assent in 1836. The finances of these early Eastern Counties railways were not happily arranged The original line was built to a gauge of 5 ft, which, a few years later, was converted to the standard gauge of 4 ft 8½ in, which did not assist matters. The trains were worked with small four-

From such beginnings sprang the Great Eastern Railway, which, in 1862, was faced with the task of salving the wreckage of the ill-

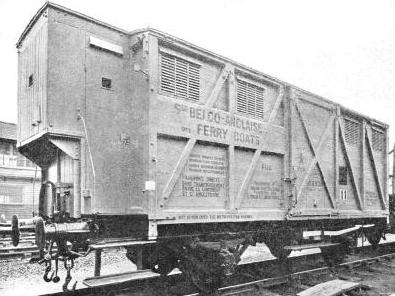

TRAIN FERRY TRANSPORT is an important part of the LNER organization. This picture shows a 20-

A new terminus in London, at Liverpool Street, was opened to local traffic on February 2, 1874, and for all traffic on November 1, 1875. To and from this station are now operated the most intensive steam-

The huge suburban traffic at Liverpool Street began with the opening of the station. Efforts were made to attract traffic to the new districts by services which at the time were unparalleled. Four trains an hour were run throughout the day, calling at all stations to Stoke Newington, and for the benefit of night workers an experiment was made in 1897 with a half-

Within its first year the line was running excursion trips for “A Day at the German Ocean”, and a chain of nineteen seaside resorts served by the railway began to develop. Residential restaurant-

London-

Thus, the Great Eastern Railway, with a mileage of 1,107 and a capital of more than £55,000,000, a fleet of eleven steamers, hotels at Liverpool Street, Felixstowe, Hunstanton and Harwich, and double line swing bridges at Reedham, Somerleyton, Trowse and Carlton Colville, which are worked by electric power, brought its quota into the London and North Eastern system.

A neighbour of the GER was the Great Northern Railway, which was the result of two rival schemes, the London and York and the Direct Northern. Like the other great railways, the Great Northern started in a very small way, the first section being the line from Louth to New Holland, for Grimsby and Hull, which was opened on March 1, 1848. Next followed other lines in Lincolnshire, and, with the opening of a line between Askern and Doncaster, South Yorkshire sportsmen travelled by rail for the first time to see the St. Leger run. About this time the main line between London and Peterborough was under construction, and on August 8, 1850, the line was opened from Werrington Junction to a temporary station at Maiden Lane, now known as York Road, some yards to the north of the present King’s Cross Station.

The opening of this line enabled trains to be run via Peterborough, Boston, Lincoln, Retford, Askern and Knottingley to York, and it also enabled the Great Northern directors to enter into negotiations with the York and North Midland, the York, Newcastle and Berwick, and the North British Railways to convey through first-

From the first the Great Northern Railway locomotives were in the van of progress. Just before the opening of the London main line Mr. Archibald Sturrock was appointed locomotive superintendent. He was an advocate of higher boiler pressures, and adopted as a standard a working pressure of 150 lb per sq in, when his contemporaries were using 80-

Apart from the East Coast route, the Great Northern system provides the principal route between London and the West Riding, Hull, and the resorts of the Lincolnshire coast, such as Skegness and Mablethorpe. These towns were developed by the enterprise of this line, which covered 1,051 miles, and had a capital of £61,500,000.

Apart from the East Coast route, the Great Northern system provides the principal route between London and the West Riding, Hull, and the resorts of the Lincolnshire coast, such as Skegness and Mablethorpe. These towns were developed by the enterprise of this line, which covered 1,051 miles, and had a capital of £61,500,000.

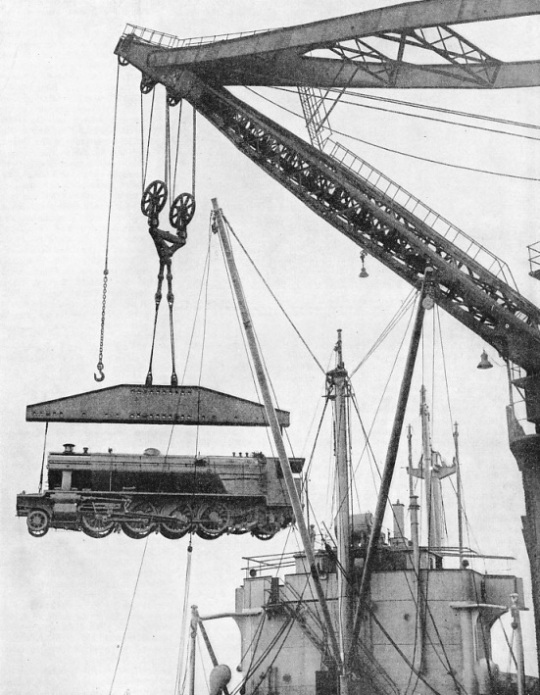

TRAIN SHIPMENT. A large engine of the “Mikado” type being lifted by crane on to a ship in the docks at Newcastle. This locomotive was built at the Armstrong Whitworth works for service in India. The LNER owns the principal docks at Newcastle.

It was from the Manchester district that the remaining partner in the romance of the London and North-

In 1847 the Grimsby Docks and other lines were amalgamated with the original company under the title of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway, known as the MSL, and the system then extended from Manchester to the East Coast. The Grimsby Docks were extended and improved, and a close alliance, made with the Great Northern Company for the running of through goods services, was consolidated by a “Fifty Years’ Agreement”. The MSL developed as a provincial system with the running of long-

The natural development of such a system was an independent outlet to the south, and for many years schemes were suggested. Several attempts were made to obtain powers for a new main line to London, for the MSL found themselves in the position of acting as feeders to their rivals possessing London termini. Heavy freight traffic was passing by east and west from Manchester, Barnsley, Wakefield and Hull, and fish was sent to London from Grimsby. Thousands of pounds were spent in fighting opposition to the new plan, and at last, in 1892, after one more strenuous effort, powers were obtained for what was known as the London Extension.

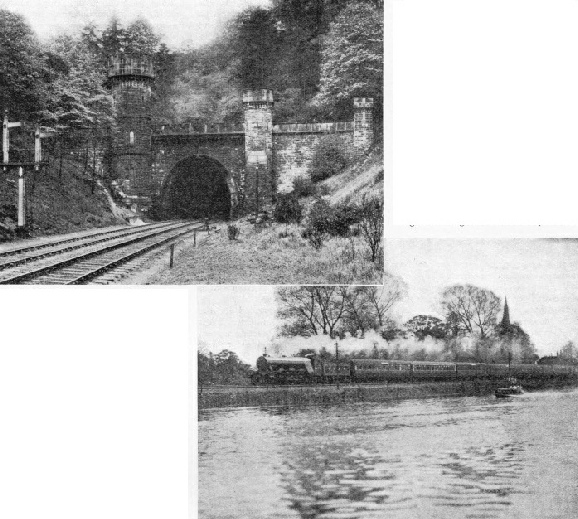

A FAMOUS TUNNEL on the LNER system. The Bramhope Tunnel between Leeds and Harrogate is 3,763 yds long. It is estimated that 1,560,000,000 gallons of water were pumped from the excavations during its construction.

THE “GAY CRUSADER”, one of the Pacific class

4-

This line stretched from Annesley to Marylebone by way of Nottingham, Leicester, Rugby and Aylesbury, and when it was known that part of Lord’s cricket ground was to be tunnelled, protests were made by cricketers, and negotiations began with the committee of the MCC. This body found that a large track of ground was to be presented to them where a clergy orphan asylum stood. The orphans were removed by the railway company, who promised the MCC that the tunnelling should only affect a part of the practice ground, and would not leave a trace after completion. Opposition from a colony of artists in St. John’s Wood was encountered, but the company proved that their ventilating shafts would not emerge near the roads and peace was made. Arbitration with landlords proved costly, but at last the engineers began on the gap of 136 miles between Annesley and London, which, after heavy engineering works, was bridged. The London Extension was opened for goods traffic on July 25, 1898, and for passenger services on March 15, 1899. Two years before this the MSL Railway took over further lines and adopted the title of Great Central Railway on August 1, 1897.

An up-

From these sources began the London and North Eastern Railway, which was formed by the Railways Act, 1921, and came into existence on January 1, 1923. The harmonizing of so many different systems was no light task, but since then much has been accomplished. The “Flying Scotsman”, which covers the 392¾ miles between King’s Cross and Edinburgh during the summer months, claims the title of the world’s longest non-

This giant wagon is one among many huge vehicles of many types in use on the London and North Eastern system. Large numbers of similar, but somewhat smaller wagons are in use for the transport of special types of machinery, particularly the transformers and plant required for Britain’s intensive developments in the use and distribution of electric power.

Other wagons are provided for the transport of very large and heavy loads such as turbine casing castings, stern frames and rudders and engines for ships. Long propeller shafts, ships’ masts, and other lengthy articles are also among the loads which the company are called upon to carry.

Special purpose vans and wagons in great variety are in use for the different classes of traffic which have to be handled throughout the company’s sphere of operations.

Long trains of high capacity wagons are employed for bringing coal from the pits to the markets of the south and the great shipping centres on the east coast of England. The weights of these mineral trains vary from 1,000 to 1,500 tons.

The company’s lines serve the famous brickyards at Fletton, near Peterborough, and the wagons in use for this traffic are each built to carry between 17,500 and 20,000 bricks.

Special wagons have been constructed to carry grain in bulk which is imported into England through the port of Hull.

Banana vans are provided to handle the imports of this fruit through London and Hull. These vehicles are fitted with internal steam heating apparatus to protect the bananas from severe frost and have adjustable ventilators for use during hot weather.

THE “SCARBOROUGH FLIER”, which runs during the summer months from King’s Cross to Scarborough, a distance of 230¼ miles, in four hours five minutes.

You can read more on “The Aberdonian”, “The Great Northern Railway”,

“The Railway Centenary Celebrations” and “Sorting Goods Wagons” on this website.