From Wooden Chariot to All-Steel Pullmans

ROLLING STOCK - 4

IN probably no branch of the railway industry has greater progress been recorded than in the development of passenger rolling-stock. The locomotive engineer rightly regards with pride the efficient and economical engines that have been evolved out of the early efforts of pioneering days; yet, in its essentials, the modern steam locomotive is not so very far removed from the primitive machines of the first half of the nineteenth century.

Between the present main-line passenger carriages and the rude vehicles which ran on our first railways, however, there is little resemblance, while in the last two or three decades the improvements effected are remarkable. Though even in the infancy of railways, some effort was made to provide a measure of comfort for travellers who were prepared to pay for it.

The modern mind finds it hard to believe that the unsightly box-like “carriages” depicted by the models and prints in the Science Museum, South Kensington, were regarded as efficient vehicles of transport in their own time; that to ride in such quaint cars was looked upon as a treat by thousands of men, women and children. Yet, the “first-class” carriages of early days then seemed marvellous chariots of travel. Many a north-country worker would save his hard-earned pence for weeks on end, so that he and his family might be privileged to journey over the Stockton and Darlington, or Liverpool and Manchester Railway, in a glorified soap-box on four wheels that did duty as a third-class passenger carriage.

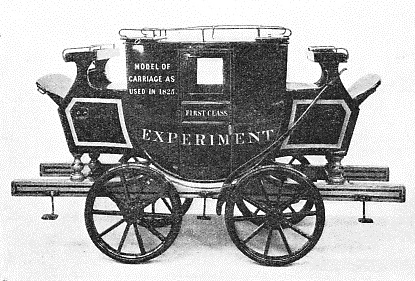

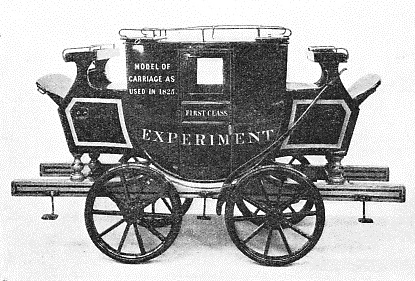

The first railway carriage expressly designed for carrying passengers was the coach “Experiment”, which made its initial run over the Stockton and Darlington system on October 10, 1825, a fortnight after the formal opening of the railway.

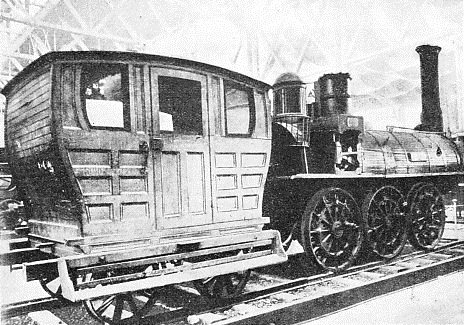

ON THE WORLD’S FIRST PUBLIC RAILWAY, the Stockton and Darlington, carriages of the pattern shown left were used. This interesting photograph is of a model belonging to the LMS in the Science Museum, South Kensington. Its close relationship to the stage coach can be clearly distinguished.

The carriage consisted of a coach body with a door at either side and the usual glazed windows, a table and seats for the inside, top seats and steps. The under-frame was supported on cast-iron wheels without springs. The seats were ranged along the sides, so that passengers sat facing one another; and it is recorded that the coach was “suitably cushioned and carpeted”, as well as being supplied with candle illumination by night. The total cost of the coach was £80, and to make quite certain of the legality of operating such a vehicle, the Stockton and Darlington directors were very careful to obtain a hackney carriage licence covering its use.

As was to be expected, almost all the early railway passenger carriages followed in their design the general lines of the stage coach. So slavishly was stage-coach design followed that practically the whole of the early carriages included a “boot” for the guard, from which he operated the brakes; and other characteristic features of the coaching era such as outside racks for luggage and special “forage boxes”.

Isambard Brunel, the engineer of the Great Western Railway, was one of the most active in developing the railway carriage proper, as distinct from the stage-coach running on rails.

In 1838 Brunel constructed a carriage which was styled a “grand saloon”. This, according to a contemporary writer, was “complete with every convenience and luxury, being most gorgeously fitted up”.

In general, however, luxury travel was non-existent for the ordinary third-class passenger of those days. Springs and spring buffers were unknown, and seating was of the hardest variety. The early railway carriages mostly took the form of box-like affairs of four or five compartments. Each ran on four wheels, with extremely hard wooden seats and upright back-rests.

With three pairs of wheels, these vehicles could not be constructed long enough for requirements without becoming too lengthy to negotiate curves safely. To overcome this difficulty the bogie truck was evolved, enabling relatively long passenger cars to be built, better suited to traffic needs.

Wooden construction throughout was generally favoured for the early carriages. With the perfection of steel manufacture big changes were made. Steel under-frames gradually came into being, leading by easy stages to the all-steel vehicle.

European passenger stock was almost all of the compartment pattern for many years, and even to-day this arrangement continues on many lines.

The break-away to the “one-room” vehicle came in 1875, when Pullman cars were introduced on the Midland (now London, Midland and Scottish) Railway. As a compromise between the compartment carriage and the saloon vehicle, the side corridor car was evolved, a type of stock much favoured throughout Europe to-day. This design retains the privacy of the compartment arrangement while affording free passage up and down the train, as well as giving connexion between the passenger sections and the restaurant and luggage cars. This also facilitates speedy entraining and detraining.

Heating, lighting and ventilation of railway passenger stock have progressed strikingly. Many people remember the foot-warmers that once were placed in the passenger compartments during the winter, and which were usually stone-cold long before the journey ended. They were oval-shaped cans containing either hot water or fused acetate of soda. and were put in the carriages after being immersed in a boiler at the terminal stations. What a contrast is this primitive arrangement to modern steam-heating! Electric lighting of passenger stock is to-day general on main lines, although incandescent gas lighting is still favoured to some degree. The evil-smelling oil-lamps of the early days did everything but light the carriage, and the change from oil to gas-lighting was a big step forward.

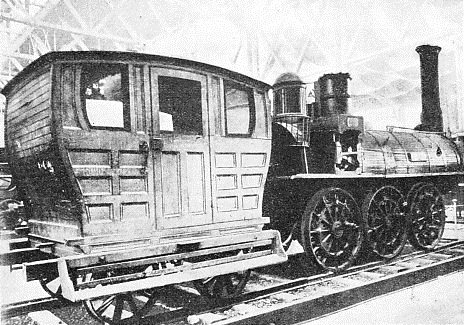

AN EARLY CANADIAN COACH. The locomotive is the “Samson”, built by Timothy Hackworth in England in 1838. The engine was originally used for hauling coal from the mines at Stellarton in Nova Scotia.

Sleeping-cars and restaurant cars are now included in almost all main-line trains operating over considerable distances. It was in 1873 that Britain’s first sleeping-car was operated. It ran over the London and North Western (now LMS) Euston-Glasgow route, and was at once a success. In 1879 the Great Northern (now LNER) Company first introduced the dining-car into Britain, cars of this type being included in the fast trains between London (King’s Cross) and Leeds. Twenty years later saw all important expresses to Scotland equipped with dining-cars.

The four main railways of Great Britain own nearly 50,000 passenger carriages - having a seating capacity of something like 2,725,000 - which include more than 500 restaurant cars, 300 sleeping-cars, and about 230 Pullmans. The supremacy of the British railways has been achieved and maintained largely by their constant endeavour to provide a degree of comfort, convenience and speed such as would satisfy the most exacting passenger, and rolling-stock of new design is continually being produced. A British first-class compartment has been described as having “the most comfortable seats of any moving vehicle”, and the sleeping-car as “the most comfortable slumber-house on wheels ever devised”.

The comfort of railway travel is well known, but it is not so generally known that the improved equipment which has contributed to this comfort has increased the weight of trains from four to twelve hundredweight per passenger. Thus, while the average steam suburban train of ten cars seats about 800 third-class passengers on a tare weight of, say, 300 tons, an outer suburban train set of the same tonnage only seats about 600 passengers, on account of the wider seating and other comforts provided. On a main-line train of ten coaches, only about 360 passengers can be accommodated, by reason of the attention devoted by carriage designers to the passengers’ comfort and convenience.

Almost all British passenger carriages are of bogie design, but on the Continent of Europe four-wheeled and six-wheeled vehicles are still being constructed for local traffic. Four-wheeled carriages, 40 ft in length, were not long ago introduced on the Northern Railway of France; while, until recently, the German Railways built four-wheeled coaches exclusively for branch-line service. Since the opening of the present century, surprisingly few four- or six-wheeled coaches have been put into service in Britain, although a number of carriages of these types remain in circulation from the nineteenth century - a testimonial to the skill of the builders, and to the excellence of the teak utilized in the construction so many years ago.

For suburban services the saloon type of passenger coach is favoured in Europe. But in Great Britain there is a tendency to revert to the compartment arrangement. This is because of the maximum amount of seating accommodation for a given floor space secured through the use of compartment stock - a very important consideration where suburban traffic is being considered.

Swing doors, opening outwards, are usual for compartment stock, but they influence the height of platform and other clearances, and on this account are open to objection. Both swing and sliding doors are utilized on the European saloon-type vehicles. Sliding doors are favoured by railways like the London Underground, where, during rush periods, the passengers travelling are in excess of the seating accommodation available.

Transverse seats are generally provided by the European lines, these being of two patterns, viz: (1) fixed seats, with only half the passengers facing the direction of travel; and (2) seats with movable backs, where all passengers face the direction of travel. Seats with movable backs are generally found in use on suburban services.

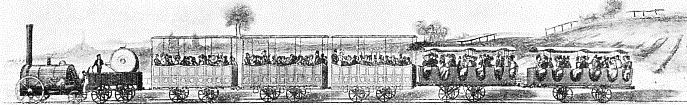

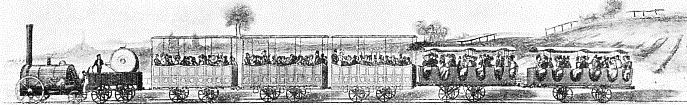

IN 1837. A passenger train of first-class carriages with a royal mail coach and - at the rear - a private road coach mounted on a truck. The locomotive is the “Jupiter” of the “Planet” class, having cylinders of 11½ in diameter, and driving wheels of 5 ft diameter.

The average weight of the British passenger carriage works out at twenty-five tons, main-line stock being somewhat heavier than branch and suburban carriages, by reason of the increased comforts and conveniences installed. Since the introduction, of grouping, a great deal has been done to standardize stock. On the London, Midland and Scottish Railway, for example, standardization has fixed the maximum width of passenger cars at 9 ft 3 in, while new passenger stock is built to four standard lengths - 57 ft, 60 ft, 65 ft, and 68 ft - with the principal component parts common to one another.

Before the amalgamation there was great diversity in the passenger rolling-stock of the constituent companies of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway. On the London and North Western, Midland, and Lancashire and Yorkshire Railways the dimensions of the coaches ranged from under 40 ft long by 8 ft wide to 65 ft by 9 ft.

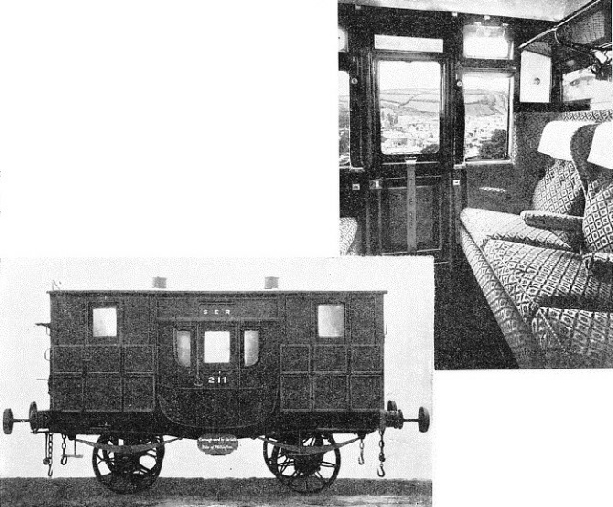

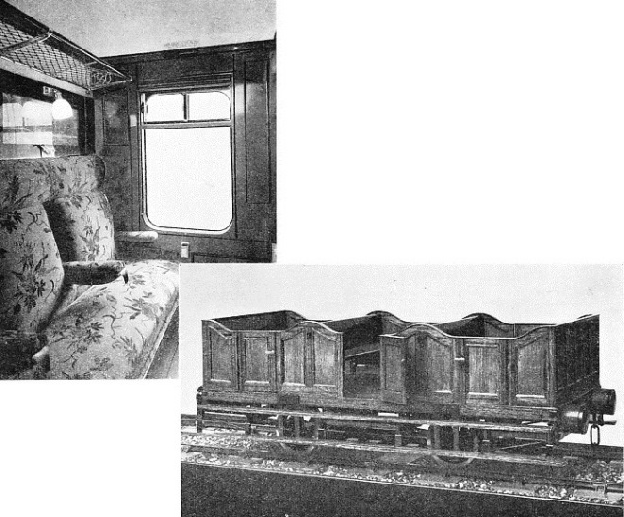

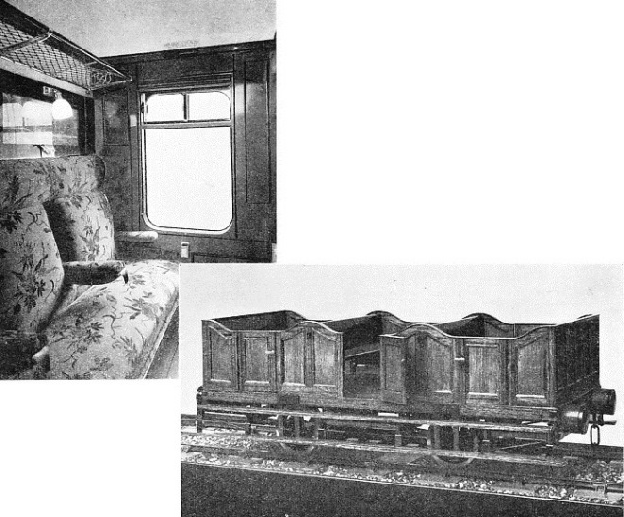

A VIVID CONTRAST is provided by these two pictures. Left is the interior of the latest type of LMS third-class coupe compartment which seats three passengers.

A VIVID CONTRAST is provided by these two pictures. Left is the interior of the latest type of LMS third-class coupe compartment which seats three passengers.

CRUDE IN DESIGN. The lower photograph shows a model of a third-class carriage of the type that was used on the Bodmin and Wadebridge Railway (Cornwall) in 1840.

Hand in hand with this standardization of outside dimensions has gone the standardization of interior equipment, furnishings and decorations. And the result has been to embody all the best features once included in the stock of the constituent companies, while discarding features of little or no value from the point of both the passenger’s comfort and convenience.

All-steel carriages are utilized to a limited extent in Great Britain, and their employment is likely to increase in the future. Some 700 or thereabouts all-steel cars are at present running in Great Britain, while across the Channel Germany leads European countries in their use. The Berlin authorities have placed no fewer than 10,500 all-steel carriages in service. France has about 3,500 vehicles of steel construction, and Italy has 2,000.

The advantages of the all-steel car lie in (1) safety, owing to the shock-resisting qualities of steel; (2) longer life; (3) mass production; and (4) elimination of vibration through the substitution of riveted or welded joints for the old wooden construction. Against these advantages, however, must be placed certain disadvantages, among which may be noted (1) increased tare weight; (2) liability to rusting; (3) conductivity of body sides, allowing variations in temperature to be transmitted to interior; (4) resonance of the vehicles; and (5) difficulties of interior decoration and fitting-out.

Passenger rolling-stock used on main lines in Britain comprises many exceptionally comfortable vehicles. A number of these are the property of the Pullman Car Company. Two long-distance trains noted for their equipment are the London and North Eastern Railway “Flying Scotsman”, and the London Midland and Scottish “Royal Scot”, both operating daily in each direction between London and the cities of Edinburgh and Glasgow.

The weight of the “Flying Scotsman” averages 425 tons, and 360 passengers are accommodated, so that more than one ton dead weight per passenger is hauled, this being largely attributable to the luxurious and roomy passenger stock. Typical passenger coaches which make up the London and North Eastern Railway expresses to Scotland include first-class cars with a door at either end, and six compartments - four smoking and two non-smoking. A side corridor gives access to the compartments, each of which accommodates six passengers in separate armchairs, with adjustable backs. Large side windows are of “Vita Glass”; footstools are provided, and an efficient arrangement of pressure ventilation and heating is employed.

EARLY RAIL TRAVEL. A train composed of second-class carriages for so-called “outside” passengers - people prepared to face possibly inclement weather with little protection. This train on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway is shown being hauled by the “North Star” which had 11 in diameter outside cylinders and 5 ft driving wheels in front. The engine, built by R. Stephenson and Co, was in the same class as the famous “Rocket”.

On the London Midland and Scottish expresses to Scotland a typical train accommodates 108 first-class and 252 third-class passengers. Its length is 846 ft, and its weight 412 tons. A variety of accommodation is provided, including compartment and saloon cars, and finely furnished refreshment cars.

On the Great Western system, new train sets for the “Cornish Riviera Express” consist of thirteen cars, each 60 ft in length, 9 ft 7 in wide, and 35 tons in weight. The cars are of fire-proof construction, the bodies being carried on steel under-frames mounted on double-bolster suspension bogies. Seating accommodation is provided for 428 passengers, and 119 diners are accommodated at a single sitting. The kitchen-cars are lined with stainless steel, and other features of the new stock are flush windows, recessed and chromium-plated door handles, and slam locks. Glazing of the carriages is with “Vita Glass”, admitting the health-giving ultra-violet rays.

Although, when compared with America and other countries, Europe cannot boast of exceptionally long railway runs, the European railways make provision for night travel on a most considerate scale. And in recent years the passenger’s comfort has been largely heightened by the inclusion of first- and third-class sleeping-cars in the principal main-line night services. Each first-class berth in the modern British sleeper is a separate compartment, and is fitted with a box-spring mattress. Specially sprung vehicles reduce oscillation to a minimum, the light in the compartment may be kept on full or dimmed as desired, and a reading lamp is invariably installed. Hot and cold running water is available in each compartment.

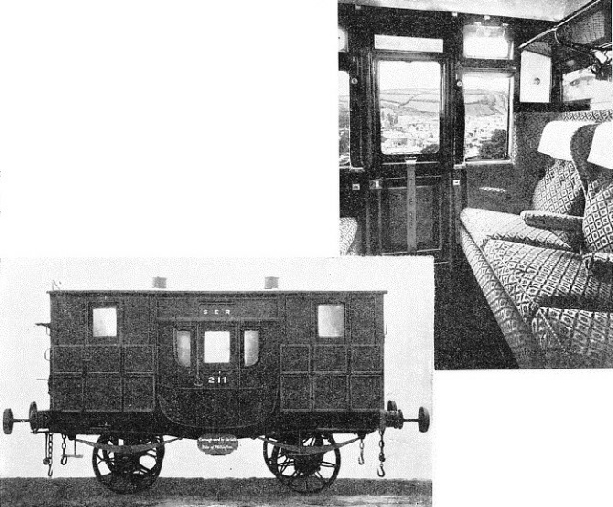

A FINE ILLUSTRATION of the luxury provided by the railways of to-day (right). This is a compartment in a first-class brake saloon on the Great Western Railway.

THE DUKE OF WELLINGTON used the carriage shown in the picture below. Coaches of this design were in use about 1838.

Third-class sleepers are a comparatively recent innovation; they run between London and Holyhead, London and Scotland, and London and the south-west. These cars usually have seven compartments, each accommodating four sleepers.

British London and North Eastern first-class sleeping-cars are all of the single bedroom type. Each car is 63½ ft long, the body being of solid teak, mount-ed upon two four-wheeled compound bolster 8 ft 6 in wheelbase trucks. The under-frame is of steel. The space between the double floor and the inner and outer sheeting of the roof and the sides of the carriages is packed with asbestos felt. Four entrance doors at both ends are provided, additional entrances being furnished by the usual Pullman vestibules linking up the corridors of the cars.

Each vehicle carries ten separate private bedrooms arranged in pairs which, if so desired, may be converted into five double bedrooms by means of communicating doors. Each little bedroom has its own full-size walnut bed, with box-spring mattress, hair and wool overlay, and two blankets. The white bed-linen is covered with a fawn embroidered bedspread.

Of vehicles of a more unusual type recently put into service in Great Britain, much interest attaches to the batch of observation cars introduced by the Great Western Railway. These take the form of first-class saloons, built with bowed observation ends. Each carriage is 60 ft in length, and is divided into an ordinary first-class compartment, with two saloons, one for use as a drawing-room and the other for dining purposes, a kitchen, pantry and lavatory. The well-appointed first-class compartment has seating capacity for six.

The drawing-room portion accommodates nine passengers, and is furnished with two settees, three upholstered chairs, a writing-table with an electric reading-lamp, and a serving table. The pantry, kitchen, lavatory and first-class compartment adjoin the side corridor connecting the two saloons at the ends of the car. The interior furnishing is in highly polished walnut; the upholstery is in figured moquette (brown and black on a beige ground); and the floors are covered with brown Saxony carpet. Primarily, these saloons are intended for the conveyance of special parties of tourists over the various scenic routes on the Great Western system.

In addition to the various luxurious vehicles named, a considerable number of Pullmans is operated over the British railways. The Southern was a leader in the Pullman movement, and the most famous British Pullman is the “Brighton Belle” - formerly the “Southern Belle” - which has run for many years non-stop between London and Brighton. Apart from this train, the Southern operates Pullmans between London and most of the south coast watering-places, as well as between London and Southampton in connexion with the American tourist business.

On the London and North Eastern line all-Pullman trains have been introduced in recent years. Among these are the “Queen of Scots” daily Pullman between London (King’s Cross) and Edinburgh and Glasgow; also the Pullman Limited trains between King’s Cross, Leeds and Harrogate. There was formerly a complete service of Pullman cars in Scotland on the Caledonian section of the London Midland and Scottish line. The Metropolitan line operates a popular Pullman service between London and Aylesbury. In Ireland, a regular daily service of Pullman buffet cars is run on the Great Southern line between Dublin and south-western points.

On the continent of Europe most of the luxury services are provided by the International Sleeping Car Company. Founded in 1876, this company now operates through trains and cars of its own over most of the principal European main-lines, by arrangement with the various railways.

The latest stock introduced by the International Sleeping Car Company takes the form of “Grand Luxe” cars for use on the Calais-Mediterranean expresses of the PLM Railway. These cars have a length of 72 ft 10 in over vestibules, and are of all-steel construction. Accommodation is given in each car for ten passengers only, in single berth compartments. The compartments are available for day and night use, the seat being convertible into a comfortable bed. The cars are fitted in a luxurious style.

Across the Channel, the Pullman Car Company operates the “Golden Arrow” Pullman between Paris and Calais in association with the Nord Railway. Other European Pullman services are those between Paris and Antwerp, Ostend and Cologne, Paris and Amsterdam (the “North Star”), Paris and the Riviera, and Paris and Madrid. Elsewhere on the Continent, the Pullman Car Company operates between Cannes and Milan, and Antwerp and Zurich (the “Edelweiss”).

The “Rheingold” express is one of the most famous of European Pullman trains. It runs between the Hook of Holland and Basle, Switzerland, and is formed of all-steel cars, comprising combination salon-dining rooms, with private compartments in the first-class section for two and four passengers respectively. Extra fares are charged on this famous German passenger train; this arrangement being usual throughout Europe for Pullman service.

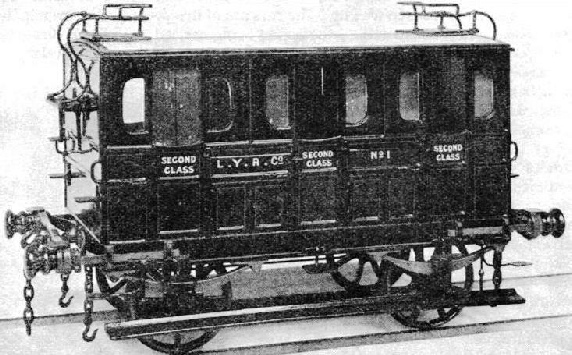

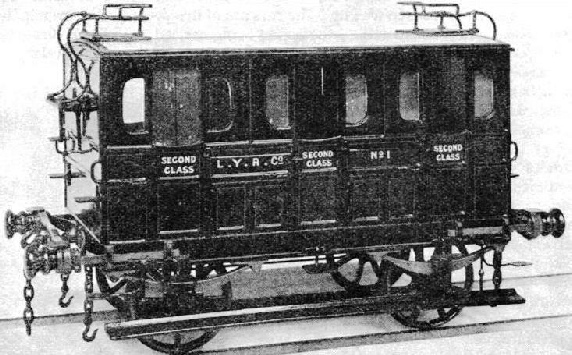

THE LONDON AND YORK RAILWAY in 1839 used the type of second-class carriage illustrated. The guard’s seats are on top of either end of the carriage.

You can read more on “Modern Passenger Rolling Stock”, “The North American Railway Carriage” and “Rolling Stock Construction” on this website.

A VIVID CONTRAST is provided by these two pictures. Left is the interior of the latest type of LMS third-

A VIVID CONTRAST is provided by these two pictures. Left is the interior of the latest type of LMS third-