© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The Caledonian Railway

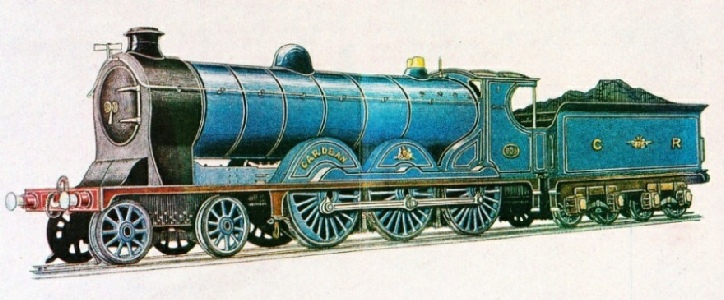

THE EXPRESS PASSENGER LOCOMOTIVE, NO. 903, DESIGNED BY MR JOHN F. MCINTOSH, M.INST.C.E.

SCOTLAND has ten railways, and if put end to end they would extend for 3843 miles, of which no less than 2267 would be single track. Four of them are short local lines working independently and of little importance; the others are the Caledonian, Glasgow & South Western, Great North, Highland, North British, and the Portpatrick & Wigtownshire worked by a joint committee which has not an engine of its own. The Caledonian, which comes first in alphabetical order, may be dealt with first, especially as at the time the Act was obtained it was believed to be impossible that there should ever be more than one railway from England into Scotland, the Caledonian beginning in England. And that was no longer ago than 1845. In the course of its development it has absorbed the successors of several of the old wagon-

Garnkirk is some seven miles eastward of Buchanan Street, Glasgow, and the line which ended at Canal Street, just behind St. Rollox, was 8¼ miles long. It came from Cargill colliery near Gartsherrie, on the Monkland & Kirkintilloch, opened in October 1826, and now part of the North British, and it ended at St. Rollox because of the canal and the chemical works into which it ran its coal wagons to tip their contents through trap-

The first Glasgow terminus was Townhead, a stone hut about 9 ft square and high, and from it five passenger trains left daily in the summer and four in the winter, business being done on artificial-

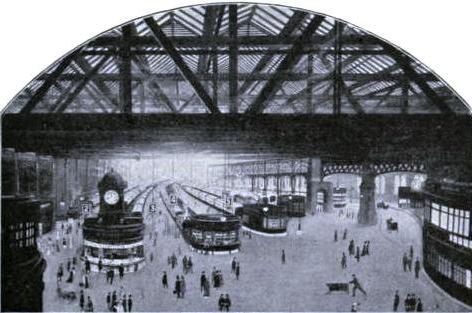

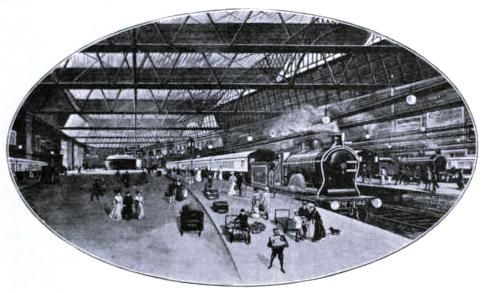

CENTRAL STATION, GLASGOW

Another railway, the Wishaw & Coltness, authorised in 1829, came to join the Garnkirk on its way, and it was to Garriongill on this line that the Caledonian was brought from Carlisle in the first section of its own making. This measured 84¾ miles; the second was the Edinburgh branch from Carstairs, which measured 27¼ miles; and the third, known as the Castlecary branch, filled in the 10 miles between Garnqueen Junction with the Monkland & Kirkintilloch, 52 chains north of Gartsherrie and Greenhill, where it joined the Scottish Central, thus completing the 122 miles authorised by the Act.

It had been long in arriving. The real trouble in the background was that there were two projects, the other being the one that had been under consideration for years in Glasgow, and has developed into the Glasgow & South Western, which was all Scottish, whereas the Caledonian was of English origin, and began with the Grand Junction. In 1835 that enterprising company sent their engineer, Joseph Locke, to survey for a line between Preston and Glasgow by way of Carlisle. Locke worked right and left of Telford’s coach road as far as Beattock, and, thinking the rise too great, he returned to Gretna and went up Nithsdale. In his report he recommended the route by this valley, and over the Cumnocks and onwards through Beith and Paisley.

This did not suit the Annandale landed proprietors; and it is a noteworthy fact that, broadly speaking, in England it was the landowners who opposed the railways, in Scotland it was the landowners who favoured them, while the landless were indifferent or antagonistic. Mr. J. J. Hope Johnstone, who owned more land in the Annandale district than any one else, sent a copy of the report to his factor Charles Stewart; and Stewart, seeing that a railway through the property would increase its value, persuaded him to take action, the result being the formation of the Committee of Annandale Proprietors in 1836, to whom the carrying through of the Caledonian project was mainly due.

A WEST COAST EXPRESS, AMONG THE LOWLAND HILLS.

Glasgow formed an opposition committee to support the Nithsdale scheme as against what had come to be called the Central; and to end the matter a proposal was accepted to have both routes gone over by different engineers, John Miller for Glasgow surveying Nithsdale, and Locke making a resurvey of Annandale. As might be expected, Miller approved the road down the Nith, and Locke found reasons for a not very enthusiastic support of the road up the Annan.

It was not so much the rise from Elvanfoot that made him doubtful, but the descent from Beattock summit “in which there is more danger”, though “perfect machinery”, otherwise brakes, “and perfect watchfulness on the part of the attendants leave no room for apprehension.” But at the same time he warned those who paid him his fee that “a plane like this ought not to be adopted without sufficient reason: you cannot expect it to be so economically worked, nor so certain in its operation as a line of equal length that is free from such a plane” -

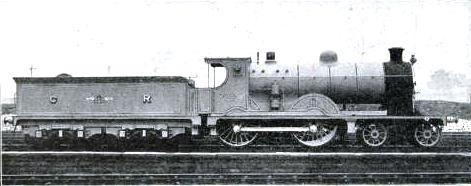

EXPRESS PASSENGER ENGINE NO. 142.

The suggestion was eventually acted upon, and after an elaborate examination of the various proposals for railway communication between England and Scotland, the Board of Trade reported in favour of the Annandale route. But the opponents were not willing to give in, and after four years’ further resistance, parliamentary and otherwise, during which the line became known as the Caledonian and assumed the Scottish arms, the Act was obtained, and the works, under Locke with Thomas Brassey as contractor, were soon in hand.

The same year, 1845, Locke and Brassey began to make the Scottish Midland, the Scottish Central, and the Clydesdale Junction. Next year the Garnkirk and the Pollok & Govan were bought. In 1847 the main line was opened to Beattock; the year afterwards it was complete to Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Castlecary; and in 1849 the Wishaw & Coltness was absorbed. Thus the road was cleared to Greenock and Paisley and Glasgow, and, by way of Castlecary and the Scottish Central, to Perth, and thence on to the Scottish Midland and the Aberdeen.

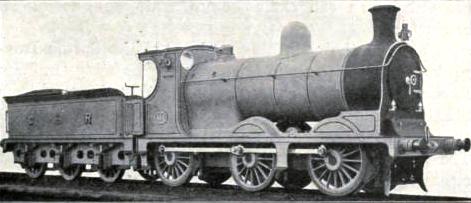

LATEST TYPE OF GOODS ENGINE, NO. 664.

For some years the Caledonian went gently, while a crowd of little lines were preparing for absorption, some of them undergoing an intermediate amalgamation like the Scottish Midland, which in 1856, taking over the Newtyle & Coupar-

Watt was the consulting engineer of the Carron Ironworks, his first partner in the steam-

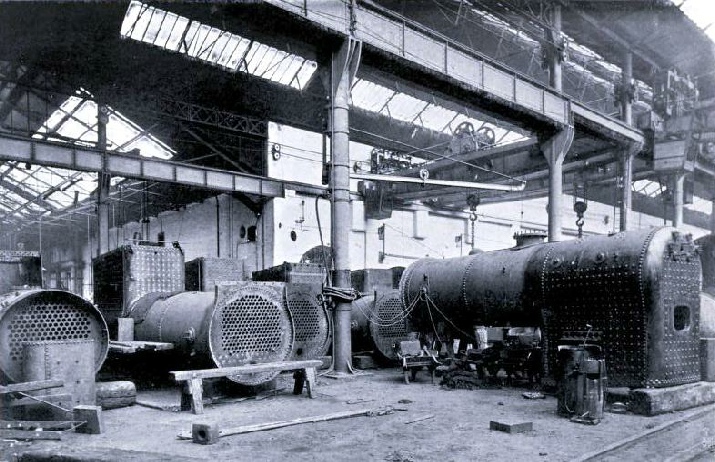

LOCOMOTIVE BOILERS AT ST. ROLLOX WORKS, SHOWING HOW THE FLUE TUBES ARE PLACED.

Nowadays the Caledonian extends from Carlisle to Aberdeen on the east coast, and to Oban and Ballachulish on the west; but Carlisle is not its most southerly station, for, by means of the branch from Kirtlebridge and through Abbey Junction, it reaches Brayton. At Lockerbie there is a branch to Dumfries, taken over in 1865, whence by the Kirkcudbright section of the Glasgow & South Western it obtains access at Castle Douglas to the Portpatrick & Wigtownshire.

This curious line is of single track throughout; it is 82 miles long, and its importance consists in its affording, from Stranraer to Larne, the shortest route to Ireland, the distance being only 39 miles, in traversing which the boats spend but little over an hour on the open sea. It runs through Galloway and Wigtownshire, with a southerly branch to Wigtown and Whithorn from Newton-

THE GLASGOW EXPRESS LEAVING PRINCES STREET STATION, EDINBURGH.

At Elvanfoot, on the Caledonian main line, a branch goes off to Wanlockhead among the lead mines, where William Symington was born, and at Symington one to Peebles on the Tweed; and then Carstairs is reached, which was the company’s first junction and the starting-

Altogether the Caledonian is nearly 1100 miles in length, and has about fifty terminal stations. In a year it carries 34 millions of passengers, 23 million tons of minerals, and over 5 million tons of merchandise; and it owns some 65,000 vehicles and 927 engines. On its main track the Beattock bank ensured its having powerful engines from the first, though on the local lines it annexed were a few miscellaneous antiquities that need not here detain us.

For opening the line Robert Sinclair, afterwards of the Eastern Counties, designed some 2-

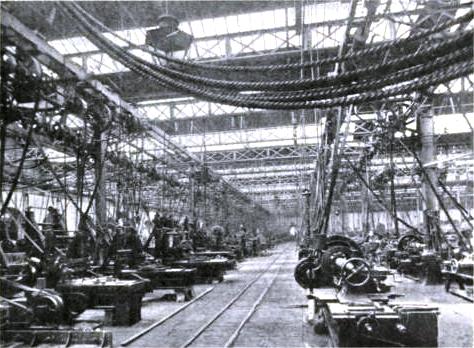

ENGINE-

In 1856 he resigned, and was succeeded by Benjamin Conner, who held the position for twenty years. Conner began with some excellent and quite famous singles with 8 ft 2-

Like Stirling’s 8-

During the race to Edinburgh his No. 123 was a 4-

In 1895 Mr. John Farquharson M'Intosh became locomotive superintendent, and soon his Dunalastairs led the way. The second Dunalastairs were 4-

CARRIAGE-

A remarkable experiment was made with fourteen of them on the 7th of September 1899 at an excursion of the people at the company’s locomotive works at St. Rollox. These 15,000 excursionists were carried in fourteen trains each of eighteen coaches all alike, and each engine was an improved Dunalastair. The first train started for Carlisle from Glasgow at ten minutes after five, the others leaving at ten minute intervals, except the last two which were twenty minutes apart. They were timed to reach Carlisle in 2 hours and 25 minutes, the return journey to take 2½ hours; and with each train out and home the time was kept to the minute. Each engine consumed 1 ton 12 cwt of coal on the journey, or 35 lb per mile; that is to say it took 3 lb 4 oz of coal to carry each passenger from Glasgow to Carlisle. Think what a wonderful thing is a locomotive that will so use the force obtained from 3¼ lb of coal as to drag a man over a hundred miles in two hours and a half.

And be it remembered that the road is far from a level one. From Carlisle it falls gently for about 7 miles to nearly sea-

The second Dunalastairs were a good class for comparison. Their cylinders being 19 by 26, the cylinder volume was 14,742 cubic in, and as their heating surface was 1500 it follows that the amount of cylinder volume for every square foot of heating surface was 9·82 cubic inches. In the Cardean, which came later, the heating surface is 2460, and consequently the volume per square foot is only 66 cubic in, the cylinders being 20-

The nature of the track had also its beneficent influence on the goods engines, which from the beginning have been workmanlike and powerful, though the engineers of sixty years since would be surprised to find their old 6-

MACHINE SHOP, ST. ROLLOX.

In his day the goods wagons were 11 ft long and held 6 tons, now by gradual increase they have arrived at 66 ft in some cases, and hold 30 tons. So long ago as 1858 the Caledonian put a 30-

When the goods station opened at St. Rollox the first day’s business amounted to the reception of three carts, the first of which brought one package, the next a cask of whisky, the third four small parcels; now 50,000 packages come to Buchanan Street in a day, and it is only one of the eleven terminal goods stations in Glasgow belonging to the Caledonian. Five million tons of miscellaneous goods in detail require some handling; and in the bulk, when added to 23 million tons of minerals, the wagons require some sorting, even on the best hump and gridiron system, as is evident any day at Ross or Robroyston.

The Caledonian crossed the Clyde into Glasgow from the south in 1879 and opened the Central Station, which twenty years afterwards had become too small and had to be enlarged, the extension necessitating another bridge across the river as well as one over Argyle Street. With the hotel it forms an imposing block of buildings, and no one who knows it would suggest a better name. It has a train in or out of it every two minutes during most of the day; the circulating area is about an acre, and there are thirteen platforms, totalling up to nearly 2 miles in length, the space and accommodation being none too large for the crowds that swarm in and out. Let it be enough to say that it is the Liverpool Street of Glasgow.

About 480 miles of the Caledonian are single track. When railways began in this country a man used to ride on the engine from one station to another and return by the next train; and, as he could not be in more places than one at the same time, safety was assured. In case of accident the old system is still in use. When worked as a single line on emergencies a pilotman, distinguished by his wearing a red armlet, accompanies every train unless more are going in the same direction, when he travels on the last engine. But for everyday working it was discovered in 1853 that the man could be dispensed with if he left his badge of office behind him. Hence for a long time a short stick like a constable’s truncheon, bearing the names of the two stations between which it could be used, was handed to the driver of the down train and brought back by the driver of the next up train, and this truncheon eventually gave place to a brass casting still called the train staff.

About 480 miles of the Caledonian are single track. When railways began in this country a man used to ride on the engine from one station to another and return by the next train; and, as he could not be in more places than one at the same time, safety was assured. In case of accident the old system is still in use. When worked as a single line on emergencies a pilotman, distinguished by his wearing a red armlet, accompanies every train unless more are going in the same direction, when he travels on the last engine. But for everyday working it was discovered in 1853 that the man could be dispensed with if he left his badge of office behind him. Hence for a long time a short stick like a constable’s truncheon, bearing the names of the two stations between which it could be used, was handed to the driver of the down train and brought back by the driver of the next up train, and this truncheon eventually gave place to a brass casting still called the train staff.

No improvement was needed on this method so long as the trains ran alternately to and fro, but when there were more trains in one direction than in the other there was no way of getting the staff back except by sending the first trains of the batch without the staff but with instructions what to do. Here was an opening for an inventor, and in 1860 the Board of Trade authorised the introduction of the Woodhouse method, which had been adopted for the working of the Standedge tunnel.

This was simple enough. The staff brought by the last train to arrive was shown by the stationmaster to the engine-

Here again there was no provision for emergencies, and none for the staff reaching a station the last thing at night when a train had to leave the other station first thing next morning. In Wales this had been met by sending the staff by horseback over the mountains, but this did not commend itself generally, and was only possible in the event of the terminals of the line being close together.

The problem was solved by the invention of the tablet system by one of the Caledonian men. In this a box at each station represents the staff, the boxes are in electric connection, in them are so many quoit-

On the North Western a method much of this character came into use in which there were no tablets but a number of brass sticks all alike, and made so that they could open any of the intermediate sidings within the section; and there are other devices, including that on the Great Western -

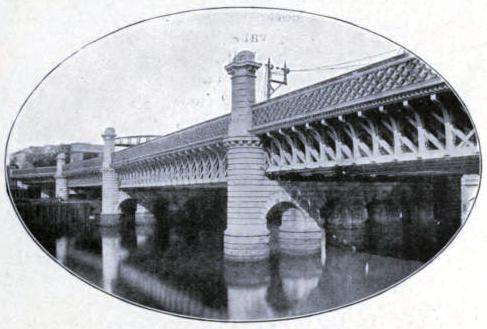

THE CALEDONIAN BRIDGE OVER THE CLYDE AT GLASGOW.

Along the Caledonian runs our principal mail train -

“The vehicles appointed to work this new postal train,” says Mr. Neele, “were all constructed with connecting covered gangways, so that the Post Office people in charge could pass from vehicle to vehicle throughout the train, and the gangways and doorways were all sufficiently commodious to allow of the transfer of parcel post receptacles when necessary to get them in position at the respective exchange stations. The sorting carriages were all brilliantly lighted, and it was a sight that must have gratified Mr. Baines” -

It was a train to be remembered; with it began the system of specials for mails only, now in vogue on so many lines; and it has grown in importance and length until it measures 150 yards or more when it starts. Its marshalling is as would be expected. Next to the engine is the Aberdeen brake van with the through bags for Scotland that require no sorting, and in the rear are the English through bags; the Scottish parcel and letter sorting vans and the English sorting vans being in the middle.

It is timed to start at half-

A SPRING HOLIDAY CROWD AT GLASGOW CENTRAL STATION.

Off it goes to the minute. In the sorting vans is the apparatus by which the bags in pouches are received and delivered as it runs, consisting of an arm and a net, the net above, the arm below. At the different places along the line where the train does not stop is the corresponding apparatus with which it gives and takes; this also consisting of an arm and a net, the net being below; and on its journey it will catch and deliver at about five dozen of these, for every one of which the pouch must be ready.

Out go the pouch or pouches on the delivering arm to be caught and the net to catch with; the electric bell starts ringing; clack cluck, the ringing stops, and at the same instant the pouches on the train have gone and the pouch from the roadside arm bounds on to the floor as if it had been shot in from a gun, and sometimes as from a battery, when, as at Bletchley, many come bumping in. Quickly, as if it were an enemy’s explosive, the pouch is opened and cleared out, and up and down the van its contents fly on to the tables and into the pigeon-

Rugby, Tamworth, Crewe, Wigan, Preston, Carnforth, Carlisle, those are the English stopping stations. At Preston the Liverpool van is left and a pilot engine goes on to help in the heavy pull from Carnforth up to Shap (914 ft) and join in the downward swoop to Carlisle.

Here in the early morning -

In a minute or so the mail is travelling to the Solway as if St. Rollox had pitted itself against Crewe in emulation of the wild career from Shap; and the seven miles down leads to the seven miles up, and makes no more difference than the four up and the four down or the following seven up and seven down, for the engine is in full swing for the gentle rise through Beattock from which it makes its effort up the hill, slowing perforce as the ten-

At Stirling some coaches from Edinburgh and Glasgow are hooked on, and the western mail packages are left behind; and thence for over thirty miles it sweeps, rushing through Crieff and Auchterarder, reeling off mile after mile at from 55 to 60 seconds each, to stop at Perth at seven minutes before six. Here the engine is changed, and before the clock strikes the hour the mail is on the way again for its flight to Aberdeen, just ninety miles in ninety-

WEMYSS BAY STATION.

The five hundred and forty miles are completed at last. It is no exceptional run, but the regular task of every weekday. And no better work is done in van or on engine than between London and Aberdeen by the special postal trains.

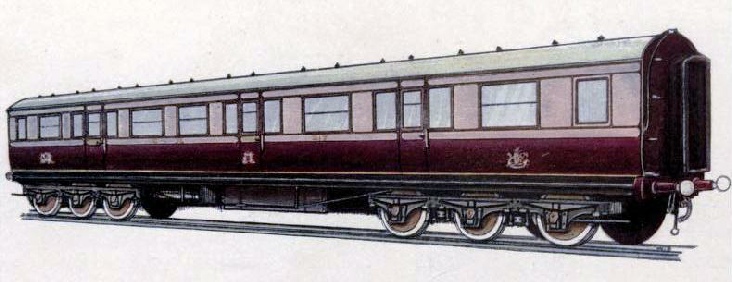

The passenger work of the Caledonian is of high repute for speed and accommodation. As we have said enough of the West Coast service we will content ourselves here with the Grampian Corridor Express as an example. This train is made up of four varieties of coaches, composite, brake composite, brake third, and third. Each of these is 65 ft long in the body, and 68 ft 6-

In the composite the space between the partitions is 7 ft 4⅝-

This heavy train -

COMPOSITE CORRIDOR CARRIAGE, NO. 217

At the other end of the varied list of passenger rolling stock is the vehicle working the local traffic over Connel Bridge, a notable cantilever structure with a span of 500 ft across Loch Etive between Connel Ferry and Benderloch, which not only runs frequently on weekdays but makes trips out and home on Sundays -

There are other bridges besides Connel that should be mentioned. Among them are the handsome bridge that crosses the Clyde at Glasgow, the Tay bridge at Perth, the Dee bridge at Aberdeen, and the two Forth bridges -

WEMYSS BAY -

Every one knows that in March 1802 William Symington’s Charlotte Dundas began work on the Forth & Clyde canal, but it is not always added that Symington had a steamboat on the canal before her in 1789 at the expense of Patrick Miller of Dalswinton, which was the successor of another boat tried elsewhere the year before. Miller was Robert Burns’s landlord. He was a director of the Bank of Scotland, and a man of ingenuity interested in many things, among others Clerk of Eldin’s idea of breaking the line which Rodney had found so satisfactory in 1780. “Why not have a ship”, thought Miller, “that can break the line in all weathers and all conditions of the sea?” That was the germ of all that followed; another instance of how the paths of war lead to the triumphs of industry.

Knowing Alexander Nasmyth, the father of the inventor of the steam-

The very thing, thought Miller. Back to the wharf came the catamaran. The new engine was the one patented three days afterwards by Taylor’s friend, William Symington of Wanlockhead, then aged twenty-

In 1786, the same year that Wilson reported to Soho that Murdock had made a model road locomotive, Symington and his brother had made “a model steam road-

Taylor introduced Miller to Symington, and a conversation followed which ended in his agreeing to place one of these engines duly adapted on board one of Miller’s boats, just as Jonathan Hulls had tried to do with an engine of Newcomen’s in 1736 (Patent No. 556), and succeeded in doing on the Avon at Evesham in 1737. Thus it came about that on the 14th of October 1788 there came forth on Dalswinton lake this noteworthy steamboat, the engine of which is at South Kensington (N. 5). She was built of tinned iron plates, and was a double-

Among the letters not long ago discovered at Soho is one from Cullen on behalf of Miller asking for estimates regarding a Watt engine to take the place of Symington’s, to which the firm replied charging Symington with attempting to evade their patent. This may have stopped Miller from going further with Boulton & Watt, for he continued to employ Symington, and used one of his engines in the boat on the Thames running between Blackfriars and Westminster in 1793, mentioned by

Carlyle, which was followed by the immediate predecessor of the Charlotte Dundas.

The Charlotte Dundas led on to Fulton’s Clermont, Bell’s Comet, and many other developments. Greenock became a steamer port, and to it in 1841 there opened the Glasgow, Paisley, & Greenock Railway which was absorbed by the Caledonian. Then the Glasgow & South Western ran in from the south through the tunnel down to the river, and got into communication with what are known as the coast steamers. In 1868 the Caledonian, intending to extend to Gourock, purchased that harbour, but had to abandon the proposed railway to it owing to the financial panic; and it was not until 1884 that they obtained the Act which gave them the needful access by the line through the tunnel, 2100 yards in length, which is the longest but one in Scotland, the longest being that of 2519 on the North British at Glenfarg. From the Greenock line at Port Glasgow they went on to Wemyss Bay, to pick up more of the profitable coast business which, as far as the steamers are concerned, is now pooled among the three great Scottish lines.

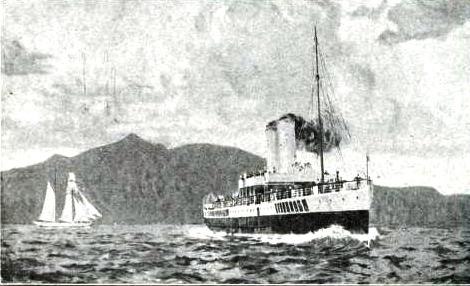

Of these boats the Caledonian own ten; the Glasgow & South Western own ten; and the North British have seven; and to these must be added the boats of the private owners. They are the famous Clyde river steamers, than which there are none better; not the launches plying in the city waters, which, be it understood, are quite another sort of craft.

The Clyde steamer, when she starts, with her spotless paint, white decks, and silver-

At first the packet companies had things all their own way in taking the people down the river from Glasgow Bridge, but things have altered, and the Broomielaw before breakfast is not what it was. The old Glasgow, Paisley, & Greenock began the new era by putting on the water the Isle of Bute and the Maid of Bute, plying from Greenock. Two more boats followed, and in 1852 the Caledonian built the first of its own, the Greenock, and the Glasgow Citizen, but it was not for another fifteen years or so that there began that combination of rail routes with steamer routes which has developed so surprisingly.

BALLOCH PIER: LOCH LOMOND STEAMER PRINCE GEORGE.

The Clyde is a curious river, practically a narrow canal with vast stretches of mud on either side at low water, and at high water assuming the appearance of a wide estuary. Unlike the Thames, which ends among flats, the Clyde ends among mountains and lakes, and it is worse near the city than the London river; but, as on the Thames, the all river route went out of fashion owing to the increasingly unpleasant state of the water to begin with; then the evidences of industrial enterprise that appeared too prominently on the banks; and then the competition of the railway companies with their cheaper fares, -

It was in 1889, when the line opened to Gourock, that a serious fight was deliberately entered upon. The Caledonian ordered a fleet of the finest passenger boats procurable, the first of which, the Galatea, was put on the river on the 1st of June 1890, and, working them in connection with the railway, soon secured the greater part of the passenger traffic with the seaside resorts round the mouth of the Clyde. The completion of the Lanarkshire & Ayrshire gave the Caledonian access to Ardrossan, and for the voyage thence to Arran there started on the 1st of June 1891 the famous Duchess of Hamilton, on which a turbine was first used for electrical purposes. For a long time, with her 18 knots, she was the pride of the fleet, a position now held by the Duchess of Argyll, which is not only lighted by turbine but driven by turbine at over 21. That these boats were and are worked with energy is clear from the Caledonian fleet running more miles in a year than there are from here to the moon; and as the other railways on both sides of the stream joined in the fray as soon as they could, the non-

A CALEDONIAN STEAMER IN THE FIRTH OF CLYDE.

You can read more on “Crack Caledonian Flyers”, “Railways of Caledonia” and “Scottish Mountain Railways” on this website.