© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

Scottish Mountain Railways

Fascinating Routes Through the Lovely Highlands

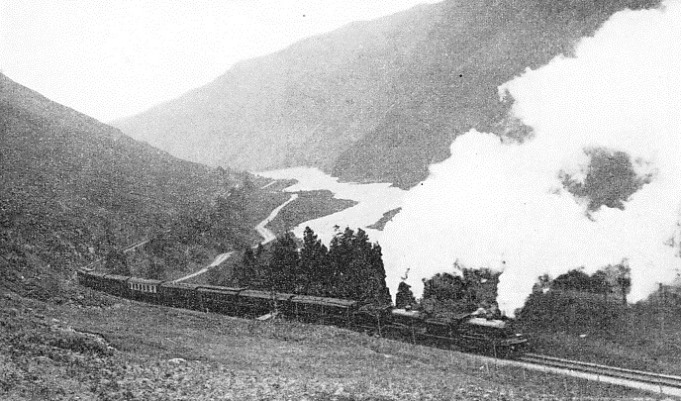

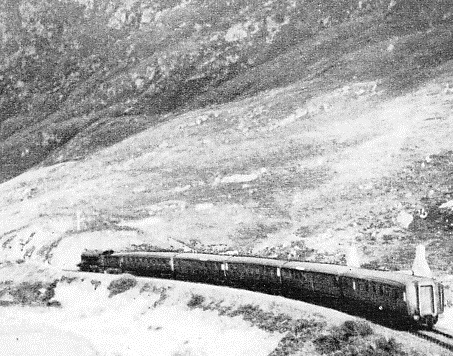

ON THE UP GRADE, A LMS express between Glasgow and Oban is shown here climbing a stiff gradient with the aid of two locomotives. The Callander and Oban line, 82 miles long, leaves the main LMS line at Dunblane, and crosses the West Highland Railway at Crianlarich.

PERHAPS the most striking of the main lines through the Scottish Highlands is the West Highland Railway (LNER) from Glasgow to Fort William and Mallaig. It is, anyway, the newest, and we shall describe it first.

At the beginning of its existence, the West Highland Railway was an independent concern, but from its opening it was worked by the old North British Railway Company. When the North British, at the beginning of 1923, became one of the constituent companies of the London and North Eastern Railway, the West Highland was absorbed by the latter. The old name “West Highland Railway” has survived, while that of the North British is perhaps already unfamiliar to the rising generation.

The West Highland Line begins at Craigendoran, a pleasant outer suburb of Glasgow on the upper Firth of Clyde, and on the Clydeside suburban line from Glasgow (Queen Street) to Helensburgh. On its way to Craigendoran, however, the West Highland train has passed the important ship-

With Helensburgh, the last of the towns surrounding Glasgow is left behind, and soon the train will have many miles of heathery waste and rough mountainside to negotiate before passing anything larger than a tiny Highland village. In view of the difficulty of the severely-

The West Highland train climbs steadily along a noble arm of the sea known as the Gareloch, hugging its eastern shore, but rising all the time on the steeply sloping hillside. From Garelochhead it crosses over a high neck of land and then proceeds to follow Loch Long in the same way. Loch Long is encompassed on both sides by high hills, but those on the west side -

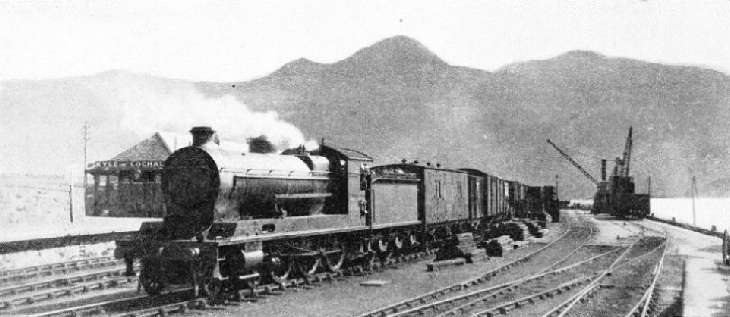

THE WESTERN TERMINUS of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway at Kyle of Lochalsh in Ross and Cromarty. The station is 650 miles from Euston London. In the background can be seen Ben na Caillach on the Isle of Skye. The railway was extended to Kyle of Lochalsh from Strome Ferry in 1897.

At the station of Arrochar the line leaves the head of Loch Long, and after crossing a great saddle of land, begins to skirt the western shore of Loch Lomond. Far below, the waters of that great and famous loch twinkle in the sun, or pucker in a rainy squall, while Ben Lomond rises like a vast purple-

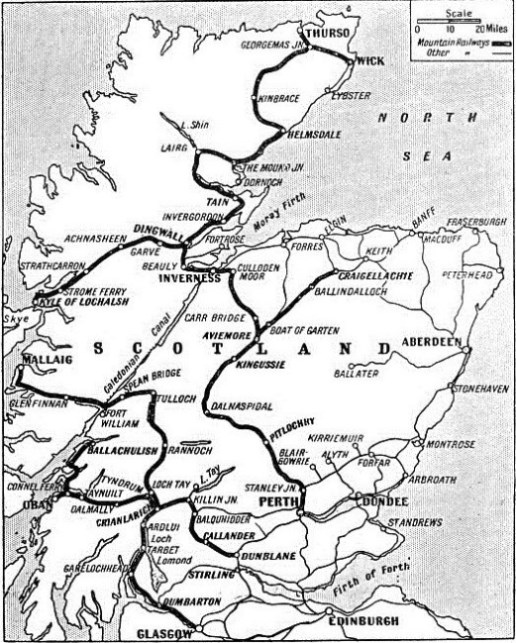

SCOTLAND’S MOUNTAIN LINES are shown on here. The companies concerned are the LMS and LNER.

Until Crianlarich is reached, the train, though bound for the north-

From Bridge of Orchy, for the next thirty odd miles, the train passes through the bleakest and wildest country possible to imagine. It is difficult to realize that Glasgow is only a few hours’ journey away and that only a night separates the train from London. The railway seems to run over the top of the world on Rannoch Moor. But to its builders it seemed more as if they were trying to lay the permanent way on the bottom of the world. The moor proved to be a gigantic repetition of Chat Moss, between Liverpool and Manchester, where every bit of material set on it at first was immediately swallowed up. Only after apparently endless toil and half-

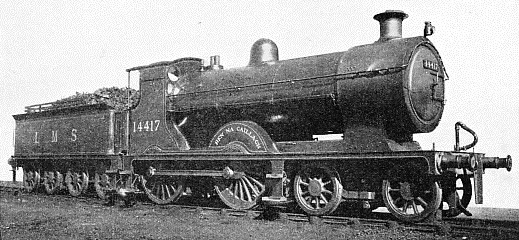

A “BEN” CLASS ENGINE of the 4-

Hereafter the line takes its snakelike course down through the flanking hills, past Tulloch, past Loch Treig, with its inky waters and with the great dams of the Lochaber hydro-

Ben Nevis, the highest mountain in the British Isles, now comes into clear view on the left-

At Fort William is the busy atmosphere of a small town contrasting strangely with the solitude through which the train has passed. The fort itself, built originally to “pacify” Highlanders such as those who held Spean Bridge, is now a flattened mound, encompassed by thick walls, and containing, together with a group of cottages, the LNER’s turntable and engine shed. The station is built on the margin of Loch Linnhe, close to the steamer pier where the connecting steamers come in from Oban and Ballachulish.

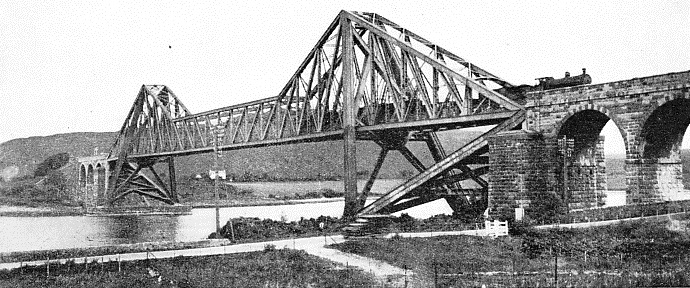

ACROSS LOCH ETIVE: the Connel Ferry Bridge. This fine cantilever construction carries the LMS line linking Oban and Ballachulish in Argyllshire.

From Fort William, which the railway first reached in 1894, there runs the Mallaig extension, completed in 1901, that passes through country of unsurpassed beauty to the West Coast, opposite the fairy-

After leaving the head of Loch Eil the line begins to mount steeply into a region of wild hills which appear to be impenetrable, except by means of a long tunnel. But by twists and turns through rock cuttings and thick birch-

Fifty-

From Glenfinnan Station the train pushes on through increasingly grand country until it reaches the indented, rock-

To the west is seen part of the Isle of Skye, with the jagged summits of the Coolin Hills in the far distance. Morar, with its famous Falls and White Sands, is passed a few miles before Mallaig is reached, when the train passes through a rock cutting into the uttermost terminus of the LNER.

It is curious that, though the West Highland line abounds in heavy engineering works, there are comparatively few tunnels, the most important being a short series between Lochailort and Arisaig. Coming down from Rannoch Moor, however, it passes through a remarkably fine example of a snow-

The other mountain line of the LNER in Scotland is remote from the West Highland excepting, of course, the Fort Augustus branch from Spean Bridge, which has one coal train a week and nothing more. The other line in question is the Speyside branch of what was formerly the Great North of Scotland Railway, far away in the east of the country. The Highlands are entered by the main Aberdeen-

The oldest mountain lines in Scotland are those which formerly belonged to the Highland Railway, now part of the LMS Railway. The earliest section of the former Highland Railway dates back to 1855. The mountain line from Perth to Inverness was built a little later. After a steady climb from Stanley Junction, on the Perth-

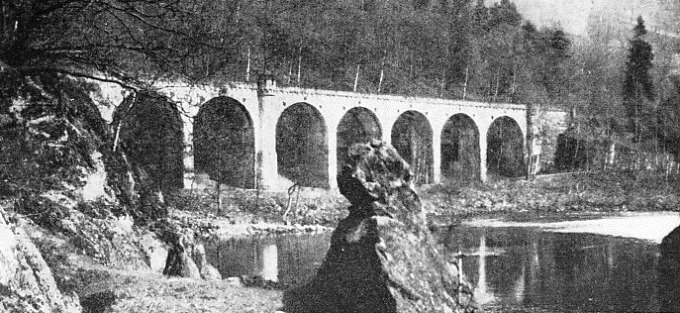

IN THE PASS OF KILLIECRANKIE, between Perth and Inverness. A masonry viaduct takes the line through the magnificent pass. This mountain line; now belonging to the LMS, was formerly owned by the Highland Railway. There are gradients of 1 in 70 on this route.

But all is calm and peaceful in the Vale of Atholl to-

Events such as these were among the deciding factors in the construction of the alternative and much shorter main line to Inverness from Aviemore, which crosses Slochd Mhuic Summit, 1,315 ft up, near Carr Bridge. On this section occur the great Tomatin and Culloden Moor viaducts. In the battle of Culloden Moor, the Jacobites were defeated by the Government on April 16, 1746. The battlefield is marked by a cairn. Coming down from Culloden Moor to Inverness, from the right side of the train the passenger enjoys an unforgettable view of the North Highlands, stretching away beyond the Moray Firth, and flanked on the east by the North Sea. Beyond Inverness the line does not enter the mountains again until it has passed Dingwall, whence branch lines run west to Strathpeffer and Kyle of Lochalsh.

The “Skye Line”, as it is called, climbs straight up into the Highland hills from Dingwall, passing below the great precipitous hill known as the Raven Rock. This line was opened to Strome Ferry in 1870, and extended to the Kyle of Lochalsh, opposite the Isle of Skye, in 1897. The climb from Dingwall to the Raven Rock involves four miles at 1 in 50, a formidable obstacle to a heavily-

Britain’s Most Exposed Line

The Skye Line is, perhaps, more at the mercy of the elements than any other British line of importance. During one bad winter, it was so completely blocked by snow that its clearance was given up as a hopeless task for some time. Achnasheen Station, in the midst of this wild but beautiful desert -

Leaving Achnasheen, the train runs in a south-

From this point the line descends to the shores of Loch Carron, a fjord running in from the sea over against the Isle of Skye, and reaches first Strathcarron, and then Strome Ferry, the old terminus of the line. Beyond this, along the newer extension to the Kyle of Lochalsh, the scenery is superb. The line itself, too, was one of the most difficult to build in Great Britain. It twists and turns along the rugged coast, through deep rock cuttings and round promontories which, at a distance, would seem impassable even to a pack-

A WEST HIGHLAND TRAIN passing below Creag Mhor (the Great Rock), between Arisaig and Morar, Inverness-

The Kyle of Lochalsh is to the Outer Hebrides and Skye what Dover is to France, or Harwich to the Netherlands. But unlike an ordinary transhipment point, the port is beautifully situated. It is connected by steamer service with Mallaig as well. Mallaig is only twenty miles away as the crow flies, but if anyone were foolish enough to try to reach it by railway from Kyle of Lochalsh, he would have to travel down to Perth, then across to Balquhidder and Crianlarich, and finally up the West Highland Line -

The final section of the old Highland Railway continues northwards from Dingwall, creeping round the coast by Invergordon and Tain to Bonar Bridge. Thence it strikes inland and enters the hills at Invershin. From Invershin there is a sharp ascent to Lairg along the eastern side of the valley of the river Shin. The hillside is so steep in one place that a great shelf of masonry had to be built to take the railway. As the train travels along this shelf, it seems almost possible to drop a pebble into the foaming waters of the river, far below in the gorge. From Lairg, the line bears back to the coast again, and at the Mound Junction, it is joined by the branch line from Dornoch, which crosses Loch Fleet on Telford’s famous causeway. Then the North Highland line pursues a relatively uninteresting course along the shores of the North Sea to Helmsdale.

The final mountain section ensues when the line once more turns its sinuous course inland and makes a wide circuit over the moors of Sutherland and Caithness. The mountains here tend to be isolated rather than to run in ranges, and the country is wild and bare in the extreme. The rails reach an elevation of 708 ft between Forsinard and Altnabreac. Snow fences and queer-

From Callander to Oban

The remaining Scottish mountain railway runs from Callander, near Stirling, to Oban and Ballachulish. It was built by an independent company, but was always worked by the Caledonian Railway, as the predecessor of the present LMS Railway. The Callander and Oban Railway is second only to the old Highland lines in seniority; it dates back to the seventies, long before the West Highland Railway was projected. Callander is situated in a natural gateway to the Highlands, not far from the famous Trossachs district. It is a place of great antiquity, like Dumbarton and Dunkeld, and was besieged by the Romans in AD 85. It is now an eminently respectable place, but less exciting. From Callander, the line winds up the steep-

From the next station, Balquhidder, a line diverges for Perth, passing through Comrie and Crierf. The Oban train, toiling up the hillside from Balquhidder, is now in the heart of the Rob Roy country. It emerges high above Loch Earn. Far below, skirting the shores of the loch, the Crieff line with its viaduct and station at Lochearnhead, looks like a very tiny and very beautiful model railway.

Bearing north-

The line now runs along Glen Dochart, past Loch Tubhair twinkling beneath Ben More, to the now familiar station of Crianlarich. The LMS station is below that of the LNER, and at right angles to it.

Leaving Tyndrum, the Oban line skirts the lower slopes of Ben Laoigh and runs southwest to Dalmally, a lovely place at the foot of Glen Orchy. Now, on this final stretch, as with the West Highland and Skye lines, comes the most strikingly beautiful country. The Oban line passes along a narrow strip of land bounded on the one side by the wide expanse of Loch Awe and on the other by the precipitous side of Ben Cruachan. The loch narrows into the deep Pass of Brander. The train then passes through Taynuilt and Ach-

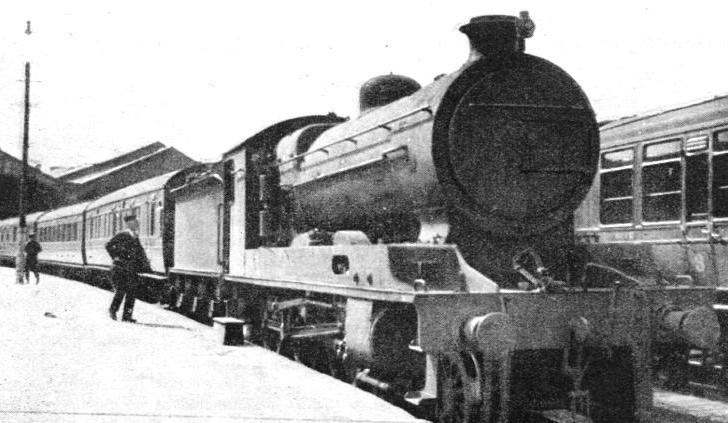

THE “ROYAL HIGHLANDER”, the famous LMS night express at Inverness, 568 miles from Euston. The Inverness portion of this express has the longest through journey run wholly on the LMS. The train is seen here headed by the 4-

You can read more on “The Forth Bridge”, “The Highland Railway”, “The Great North of Scotland Railway” and “The Railways of Caledonia” on this website.

You can read more on “Bridges in the Highlands” in Wonders of World Engineering