RAILWAYS OF BRITAIN - 43

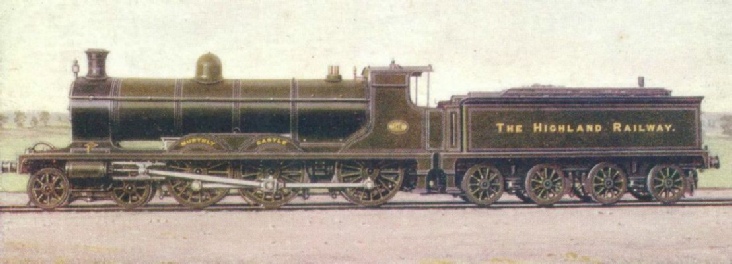

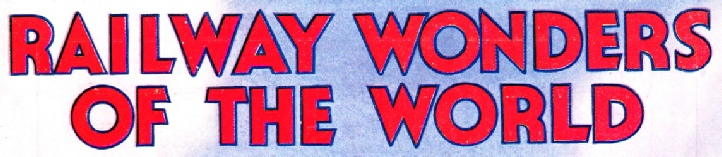

HIGHLAND RAILWAY 4-6-0 “MURTHLY CASTLE” No. 145. DESIGNED BY PETER DRUMMOND.

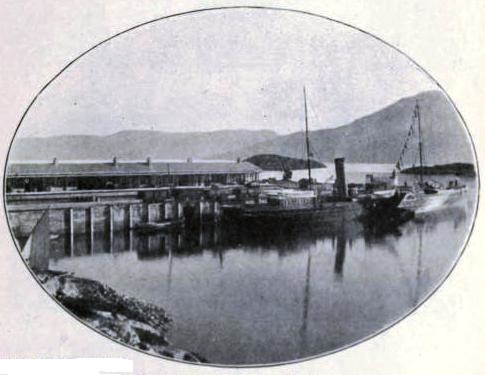

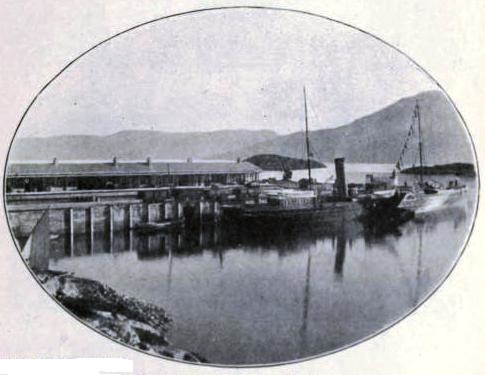

THE Highland Railway does not reach Perth, as generally-supposed, but comes as far south as Stanley Junction, within eight miles of it, the intervening line belonging to the Caledonian; and it runs right away up to Thurso on the Pentland Firth, or rather at its western entrance. To the east from Inverness it reaches Portessie on the Moray Firth, and on the west it ends at Kyle of Lochalsh opposite Skye.

Railway cartographers - that seems to be the correct term - nearly always manage to make their main line look straighter than that of their competitors and fill in the details to fit, but the Highland, perhaps because it has no competitor for the most part, or that the attempt was hopeless, gives the line just as it is, a most meandering route to the far north. For the sinuous course, however, there are two good reasons, one the difficulty of dealing with mountain and valley, the other the policy of the projectors, who in a commendable spirit thought less of the dividend than of the development of the country.

And so, like the outline of a dissected puzzle, it swings westward to Dalnaspidal, eastward to Aviemore, westward to Beauly, eastward to Fearn, westward to Lairg, eastward to Golspie on the coast, then up the coast and westward to Forsinard and northward to Georgemas, our most northerly junction, where it branches south-eastward to Wick and north-westward to Thurso. From Stanley Junction to Thurso, as the crow flies, is 135½ miles; and by the Highland Railway it is just double as far.

INVERNESS STATION.

It began with the Inverness & Nairn, fifteen miles long, which opened in November 1855, and became in 1861 the Inverness & Aberdeen Junction by amalgamation with the then three-year-old line from Nairn to Keith. In 1863 the Perth & Dunkeld, opened in 1856, was absorbed, as was also its continuation the Inverness & Perth Junction, and in 1865 the amalgamated companies took the name of The Highland Railway.

Meanwhile the lines were being pushed northwards. The Ross-shire Railway, Inverness to Invergordon, was opened in 1863, and extended to Bonar Bridge in 1864; the Sutherland Railway from Bonar Bridge to Golspie was opened in 1868; the Dingwall & Skye, to Strome Ferry, was opened in 1870, and extended to Kyle of Lochalsh in November 1897. In 1871 the Duke of Sutherland - “the real duke who drove his own engine on his own railroad and burnt his own coals” - made a railway from Golspie to Helmsdale, and the final stage in this direction was reached when the Sutherland & Caithness from Helmsdale to Wick and Thurso was opened in 1874. Within the next ten years all these were merged in the Highland, which grew by extension and absorption until it now has a length of 485 miles and 146 engines, with a united annual mileage of over 2,800,000.

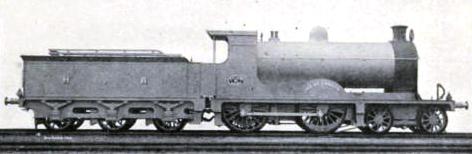

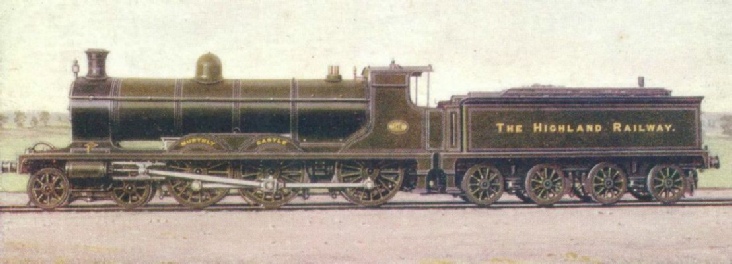

EXPRESS PASSENGER ENGINE NO. 61, “BEN” CLASS.

The Highland has always had good engines, well kept and smart as though their drivers took a pride in them. There is no mistaking them in their green livery, without referring to their Gaelic names which look so alarming and sound so sonorous. The first locomotive superintendent was William Barclay; he, after ten years of office and an interval, was followed by William Stroudley, who came from Cowlairs, where he received the yellow inspiration he took on to the Brighton.

To him was due the invention of the snow-plough that fixed on the front of the engine with the cap of the chimney peeping over the top, for the Highland is much troubled by snowstorms and rough weather, and even doubles its chimneys, putting louvres in front of the outer casing to stop the blustering wind checking the draught through the fire.

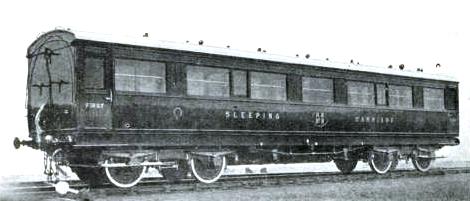

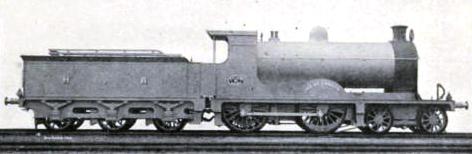

COMPOSITE CORRIDOR SLEEPING CARRIAGE NO. 8.

Stroudley was succeeded by David Jones, who had been in the company’s works from the beginning when it possessed but a couple of engines, five coaches (in good condition as they always have been), and just six-and-twenty wagons. His engines were mainly 4-coupleds, including the Strath class of 1892 and the more powerful Lochs of 1896. His 4-6-0’s with 20-in by 26-in cylinders were the first of the type in the island, and for some time the most powerful main line engines on the rail.

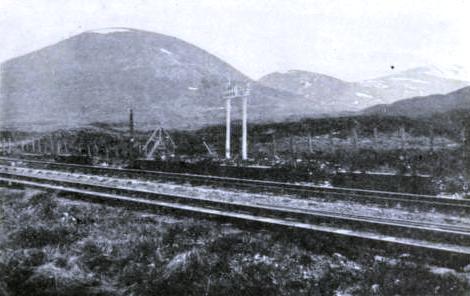

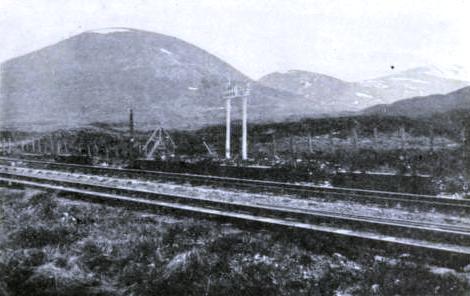

THE HIGHEST SUMMIT LEVEL IN BRITAIN, 1484 FT. BETWEEN DALNASPIDAL AND DALWHINNIE.

Though the passenger expresses between Perth and Inverness are drawn by the Castle class of 4-6-0’s with cylinders 19 by 26, 5 ft 9-in wheels, and a heating surface of 2050, the 4-4-0 engine maybe described as the dominant type of the line, the most recent designed by Mr. Peter Drummond continuing the tradition. The goods engines are also noteworthy, as, for example, those like No. 134, a 6-coupled with 5 ft wheels and 18¼-in by 26-in cylinders, or No. 19, a 6-coupled with 5 ft 0½-in wheels and similar cylinders, with a heating surface of 1307 including that of the water-tubes in the firebox. There are also a few good shunting engines such as the 6-coupled tanks with 5 ft 3-in wheels, 18-in by 24-in cylinders, and a heating surface of 1179.

Just as the Beattock bank made the Cale donian engines good from the first, so have the curves and gradients of the Highland had their effect. Power had to be had, sometimes at both ends, as even in these days, to get the trains along its undulating track.

donian engines good from the first, so have the curves and gradients of the Highland had their effect. Power had to be had, sometimes at both ends, as even in these days, to get the trains along its undulating track.

From Perth you go north through the picturesque to the desolate. Perth is a joint station belonging to the Caledonian, with the Highland and North British as junior partners, and it has long been proverbial for its exhibitions of rolling stock. Your train is the harlequin, so called from its being made up of patches of through coaches and vans from every line of importance, Scottish and otherwise.

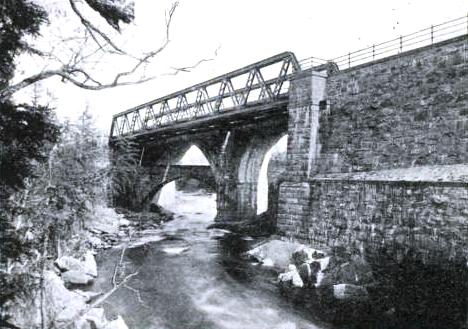

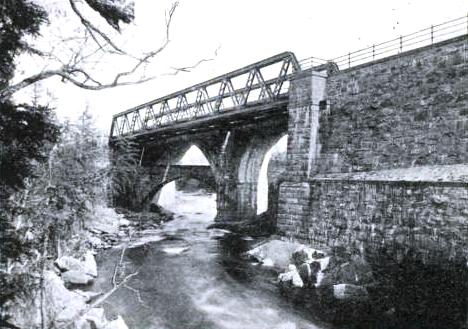

Up through Perthshire you go with its beautiful woods and hillsides; past Dunkeld with its larches, the first planted in Scotland and that as far back as 1738; over Dalguise Bridge across the Tay; through Pitlochry and the Killiecrankie Pass, over a curving, ten-arched viaduct 40 ft above the bed of the stream; then on over the Garry tossing along its rocky bed below you, and farther over the bridge likewise 40 ft above a river, through the deep cutting to Dalnaspidal, climbing to the summit level, 1484 ft above the sea, and descending swiftly to bleak Dalwhinnie. Kingussie is then reached, with the Grampians well behind you, and on you go through Aviemore, to cross the Findhorn by the steel bridge that carries you 145 ft above it, and then the Nairn by the long red sandstone viaduct of 28 arches rising 135 ft from the river, and so by Culloden Moor to Inverness the beautiful, the capital of the Highlands and the heart of the Highland, for there are its headquarters and its locomotive works.

From Aviemore the old roundabout route will take you past Boat of Garten, the western outpost of the Great North, and up by steep gradients to the Knock of Brae Moray and down again to Dava. Then you speed over the Divie Bridge, which, like so many of the other viaducts, begins and ends with battlemented towers, and down to Dunphail, and on to Forres through the mighty cutting and along the embankment that is just 77 ft high. Farther north, if you would see the scenery of the west, the sternest and wildest of Caledonia, you go off the main line at Dingwall, and begin by climbing the Raven’s Rock for four miles at 1 in 50 before you get really going on your way to Strome Ferry and beyond.

BRIDGES AT STRUAN STATION.

From Inverness on your northward way you continue going west for a time over the Ness Bridge and the swing bridge across the Caledonian canal, skirting the three firths - of Beauly, where you turn to the right, Cromarty and Dornoch - to Bonar Bridge, and up the romantic course of the Shin, by cutting and embankment, to that anglers’ gathering place, Lairg, and then to the coast again, and along to Helmsdale with the Duke of Sutherland’s private station - one of the five private stations in this island - at Dunrobin. Ascending the river you reach Kildonan of the gold diggings, and cross the country of the snow-drifts to Altnabreac, and so on to Georgemas. Wick, to the south-east, is fourteen miles away, and there you get the fishery world displayed, with herring-boats and other boats and accessories that never fail to be interesting. Seven miles north of Georgemas and nineteen miles from Wick lies Thurso, and in the corner between them is Duncansby Head with John o’ Groat’s. Such is the Highland Railway, the grandest route in Britain.

STATION AND PIER, KYLE OF LOCHALSH.

You can read more on “Great North of Scotland Railway”, “Railways of Caledonia” and “Scottish Mountain Railways” on this website.

donian engines good from the first, so have the curves and gradients of the Highland had their effect. Power had to be had, sometimes at both ends, as even in these days, to get the trains along its undulating track.

donian engines good from the first, so have the curves and gradients of the Highland had their effect. Power had to be had, sometimes at both ends, as even in these days, to get the trains along its undulating track.