The Steel Highway in Beautiful Scotland

RAILWAYS OF BRITAIN -14

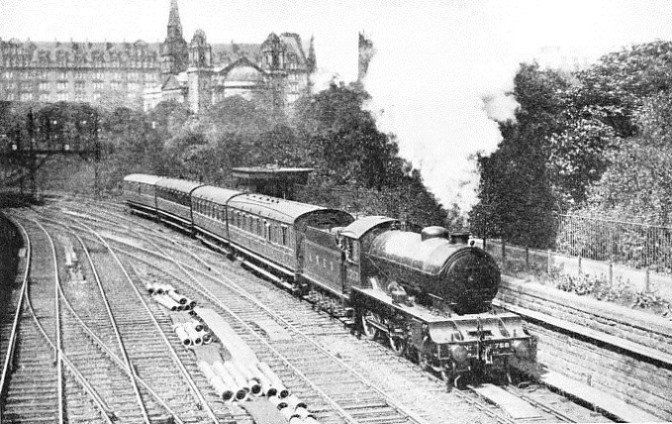

A MANY-TRACKED APPROACH to the LNER terminus at Edinburgh, Waverley Station. The station has nineteen platform lines, handles over 600 trains a day, and occupies an area of eighteen acres. The longest platform at Waverley measures 1,680 ft. Many well-known trains use this station, including the LNER “Flying Scotsman” and “Highlandman”, as well as through LMS expresses to and from the Midland Section via Carlisle.

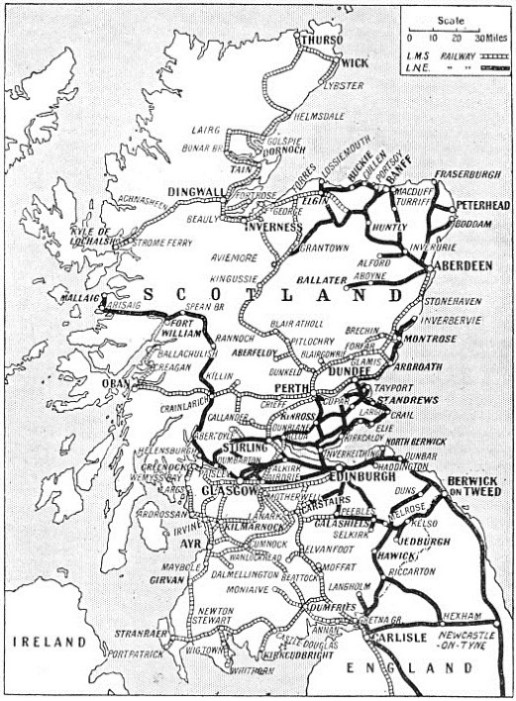

UNTIL January 1, 1923, when the Railways Act of 1921 brought into being the Big Four of to-day, Scotland had her own railways, owned and worked by five principal companies. Of these five the greatest were the North British Railway, with a total route mileage of 1,377, and the Caledonian, which covered 1,114 miles. The Great North of Scotland Railway, with its main line running from Aberdeen to Elgin, was, in spite of its ambitious title, the smallest of the five, having a route mileage of only 334. But this railway company had considerable ambitions at the time of its incorporation. The Great North of Scotland had always wanted to get at that key of the north, Inverness. But Inverness was considered to be a very strict preserve of the Highland Railway. The Great North never succeeded in doing more than running through trains to the Highland capital, while the Highland, in its turn, ran through trains over the Great North into Aberdeen. This friendly arrangement came into being only after the two companies had behaved to one another in a highly warlike way for about a third of a century, or even longer.

The Highland, with a route mileage of nearly 506, chiefly single track through wild and mountainous country, will receive fuller attention in another chapter. The remaining Scottish railway company was the Glasgow and South Western, with a route mileage of 493. This railway had a little monopoly in the south-western corner of Scotland. That monopoly was invaded, however, by the Portpatrick and Wigtownshire Joint Railway, which connected the Border country and the North of England with the important port of Stranraer, the jumping-off place for Northern Ireland. This joint line might have been described as a pie in which the Caledonian had a strong finger. It was jointly worked by locomotives and rolling-stock of the Caledonian and Glasgow and South Western.

LOCH TREIG in the Western Highlands of Scotland. This photograph was taken from the window of a London and North Eastern Railway train passing along the loch shore.

With the coming into force of the Railways Act, the Caledonian, Highland, and the Glasgow and South Western became merged in the London, Midland and Scottish, while the North British and the Great North of Scotland had their identities sunk in the present London and North Eastern Railway. Thus these two great companies now divide Scottish railway traffic between them. A peculiar thing happened as a result of this incorporation of the Great North in the LNER. The old North British had access to Aberdeen only by means of running powers over the Caledonian between that city and Kinnaber Junction, which is a little to the north of Montrose. The LNER, as its successor, still exercises running powers over the Caledonian section of the LMS. But the main line of the Great North, or the Northern Scottish Division of the LNER, as it is now called, comes no farther south than Aberdeen. The result of this is that, to-day, the northernmost lines of the LNER are completely cut off from the rest of the system except by running powers over a considerable section of the LMS Railway.

The old North British Railway, though the biggest system in the country, was not the most popular; that distinction was possessed by the Caledonian. The best Caledonian expresses were equal in comfort to the finest trains in England, while those of the North British certainly were not. The beautiful blue Caledonian engines, with their chocolate underframes and their trains of neat brown-and-white carriages, attracted the public eye. Between Forfar and Perth, too, the Caledonian had, sometime before the War, the fastest booked run in Britain. The company worked in close co-operation with the London and North Western, which was looked upon as one of the best railways in the world; and, though it had not such ambitious features on its route as the North British Railway’s Forth and Tay Bridges, it carried its passengers through some of Scotland’s most beautiful country. For these reasons, coupled with the fact that three out of the old five Scottish systems are involved, we will deal first with the Scottish lines of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway.

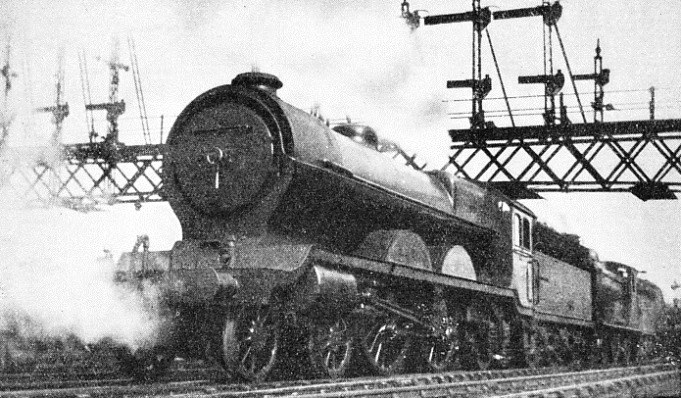

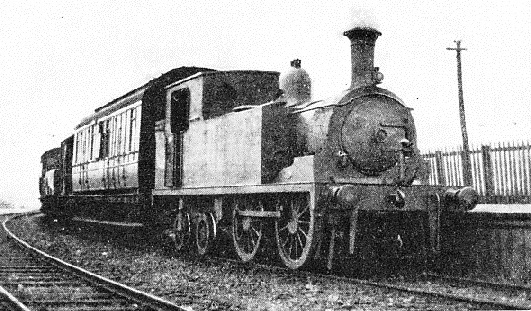

THE EDINBURGH EXPRESS leaving Aberdeen. The train is drawn by two LNER locomotives, the “Thane of Fife”, an engine of the well-known North British “Atlantic” type and, behind it, the “Caleb Balderstone”, with the 4-4-0 wheel arrangement.

The LMS West Coast Route affords at Carlisle a most impressive entrance to Scotland, whether made in the early morning or in the late afternoon. Though it is something like one hundred and ninety years since armies went into action in these islands, Carlisle still resembles a frontier town. The station itself is named after the Citadel, and passengers for the north can see that grim fortress still frowning at the Scottish hills across the flat plains of the “Debatable Land”. Crossing the Border between Gretna and the signal cabin at Quintinshill, the train has a forty-mile climb ahead, culminating in the ten miles from. Beattock to Beattock Summit, through grandly stern hills, on a gradient varying from 1 in 88 to 1 in 69. At Carstairs one line goes eastwards to Edinburgh, topping another formidable climb at Cobbinshaw. The main line from Carstairs to Glasgow descends through Wishaw and Motherwell, running into the Central Station on the north side of the Clyde, which it crosses immediately beforehand. From Law Junction to the south of Glasgow a line diverges and passes through Coatbridge to Larbert, whence there is a clear run to Perth, Aberdeen, and Inverness, via Stirling.

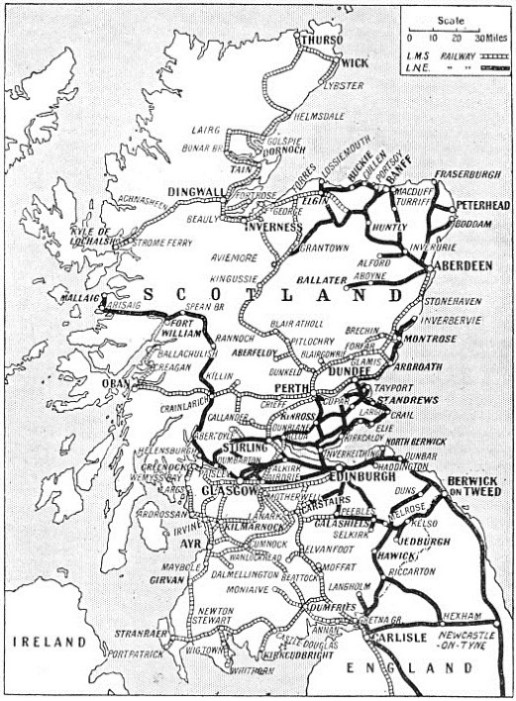

THE SCOTTISH RAILWAY SYSTEM is illustrated in this map showing the main lines and the principal towns they join.

The Aberdeen and Inverness lines part company at Stanley Junction, a little to the north of Perth. The line from Stanley Junction to Inverness, which formerly belonged to the Highland Railway, is the most remarkable of all British main lines. It takes the passenger over the Grampians by way of Drumochter Pass, the summit level being at an altitude of 1,484 ft above the sea, between the stations of Dalnaspidal and Dalwhinnie. This is the highest level reached by any British main line. Another formidable summit on the same line is reached at Slochd Mhuic (1,315 ft), between Aviemore and Inverness. Up the Tay valley and onwards up Glen Garry, past Blair Atholl, the country crossed is exceedingly beautiful. Across Drumochter Pass and beyond, trees become smaller and not too plentiful, while the hills are grandly wild. North of Inverness, at Dingwall, the main line divides, one branch going off to the West Coast at Kyle of Lochalsh, while the other follows a devious course up to Wick, Lybster, and Thurso. The last-named place is the northernmost town in Great Britain to be reached by railway. From the point of distance, however, Lybster is the extreme terminus of the LMS, and for that matter, of the British railway system. Except for a little way along the shores of the Beauly Firth, the whole of the LMS main line north of Inverness consists of single track, worked by the electric train staff system. The engines carry apparatus for the automatic exchange of the tablets so that speed is not so diminished as it would otherwise be. In the far north the train passes through some of the most bleak country in Europe; the line is protected by wooden snow fences and “blowers” at the, most exposed places, for drifts can form in a surprisingly short time when the wind whips up the dry snow on the bare moors of Sutherland and Caithness.

This Highland main line is a difficult proposition; powerful engines and the double heading of important trains have always been the rule. The old Highland company was the first British railway to introduce the 4-6-0 type of engine, which it did as far back as 1894. When the construction of the line across the Grampians was in progress in the eighteen-sixties, many experts declared that no locomotive would ever climb such hills. In at least one place on the line to Caithness the permanent way rests on the peat bogs, and the whole embankment trembles with the passage of a train. The remaining main line of the old Highland system runs eastwards from Inverness to join the LNER at Elgin, and again at Keith.

To the Granite City

Returning to Perth, the main lines to Dundee and Aberdeen must be mentioned. The first-named is straightforward enough; it follows the valley of the Tay down to the great and ancient - though not particularly beautiful - city of jute, marmalade, and shipping. The Aberdeen line runs in a north-easterly direction through Forfar to Kinnaber Junction, whence it continues along the grand, rock-bound East Coast as far as the Granite City. The LMS throws another tentacle out to the West Coast beside the Kyle of Lochalsh line. This leaves the main line a little north of Stirling, and runs through Callander, Crianlarich, and Dalmally to Oban and Ballachulish, passing through the most superb scenery. A cross-country line leaves it at Balquhidder, and goes through Crieff and Comrie to Perth. On the Oban line special precautions have to be taken against falls of rock on the permanent way, where the track winds along the bases of the mountains. During the season a special observation car runs daily on one of the Glasgow-Oban trains. This was formerly the Pullman observation car “Maid of Morven”.

The LMS serves also a number of important towns and watering-places on the Firth of Clyde, most of them situated on the former Glasgow and South Western line. That company also owned the long single-track main line which bears southwards from Maybole, linking Glasgow with Stranraer, for Ireland. The old Glasgow and South Western main line runs down to Carlisle through the midst of the Burns country. Though less hilly than the route used by the West Coast trains, it climbs over a by no means inconsiderable summit between Sanquhar and New Cumnock.

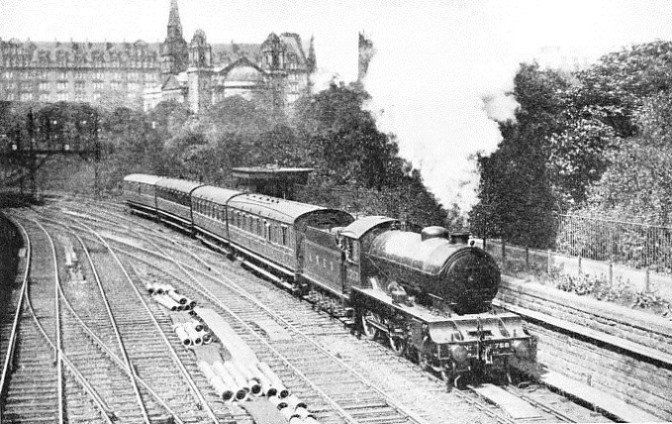

“NORTHUMBERLAND”, LNER engine No. 2758 of the “Shire” class, passing through Princes Street Gardens, Edinburgh, hauling the up Kirkcaldy train. Kirkcaldy, in Fife, is 26 miles from Edinburgh by rail across the Forth Bridge.

The London and North Eastern Railway enters Scotland by two gateways, Carlisle in the west and Berwick in the east. Several of its local cross-country lines also cross the Border. Indeed, the LNER has the beautiful Border country more or less to itself. On the English side there is the Newcastle and Carlisle line; on the Scottish side the picturesque Waverley route passes through Hawick, St. Boswells, Melrose and Galashiels on its way from Carlisle to Edinburgh. In the pre-grouping days the Midland Railway and the North British operated, by means of the Waverley route, a half-hearted competitive service to Edinburgh against the West Coast companies. The journey took longer and was more difficult, but not a few people preferred it because of the intensely interesting and romantic country through which the trains passed.

The LNER main line from Berwick to Edinburgh, Dundee, and Aberdeen, is, of course, simply a link in the “Great North Road of Steel”, and, as such, is already too well known for further comment to be necessary. It is worth pointing out, however, that the company has the whole of the industrially rich county of Fife to itself, a monopoly previously enjoyed by the North British Railway. The LNER has changed and greatly improved railway operation in Fife. To-day the traveller can enjoy the experience of crossing the Forth and Tay Bridges in trains as good as any in the country, although formerly rail transport in this part did not have a high reputation. For all its industrialism, too, Fife has many beautiful parts which are little known to the ordinary tourist.

Rope-Hauled Expresses

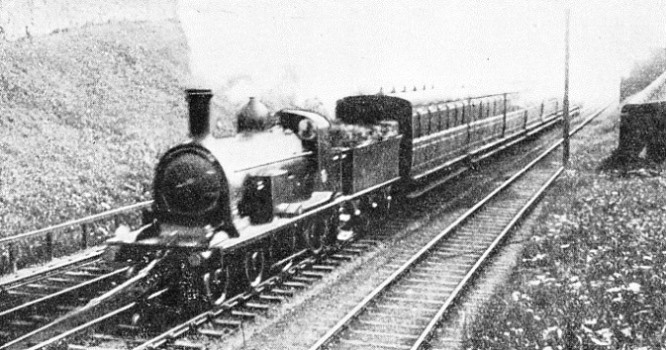

Far back in the last century the North British amalgamated with the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway, and it was this company which built the present main line of the LNER from the Scottish capital to the Scottish commercial metropolis. The route is flat and makes for easy running all the way from Edinburgh to Cowlairs, on the northern fringe of Glasgow. Thence it drops into the city by means of one of the steepest inclines on any British main line. For years - right into the present century - all trains leaving the Queen Street terminus via Cowlairs were assisted up the incline, engine and all, by means of an endless rope worked by a stationary engine at the top of the hill. On the front of the locomotive was an inverted coupling hook. This was attached, by means of a “messenger” rope, to the main endless wire rope. When the signal was given for the train to start, an electric bell was rung in the stationary engine house up at Cowlairs, so that the locomotive and the endless rope started pulling simultaneously. At the top of the hill, when the gradient became easier, the locomotive, still straining hard, naturally gained on the rope, with the result that the “messenger” rope dropped off. This obviated the need of stopping and uncoupling it. At the same time the special brake vans which were employed on the incline were slipped from the back of the train. Incoming trains had their locomotives detached at Cowlairs. A number of the special brake vans were then attached, a shunting engine gave the carriages a push, and the whole cavalcade tobogganed solemnly down to Queen Street. Nowadays heavy trains are banked up the incline by powerful tank engines provided with special slip couplings, so that they can drop off from the rear of the moving train as it passes through Cowlairs Station.

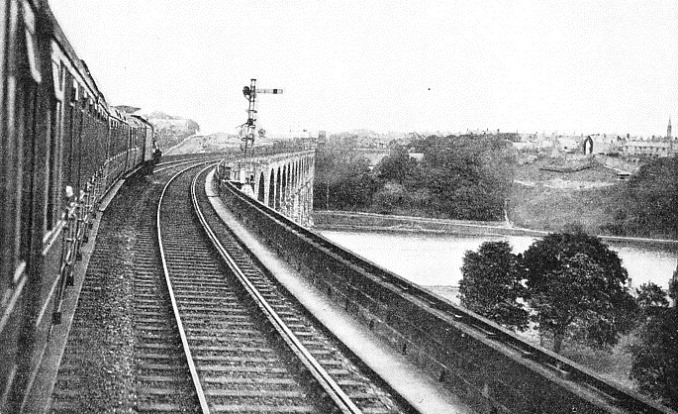

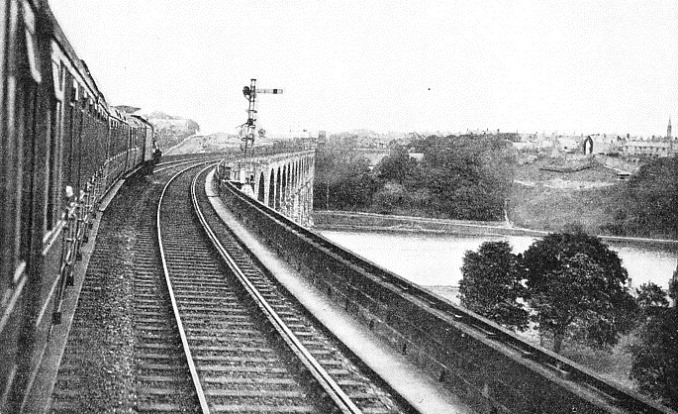

CROSSING THE ROYAL BORDER BRIDGE. The bridge spans the River Tweed at Berwick and forms a railway link between England and Scotland. The structure is 2,160 ft long, and has twenty-eight arches. At the highest point the track lies 126 ft 6 in from the river bed to the parapet.

Altogether there are three main lines between Edinburgh and Glasgow, for, in addition to the rival LMS line, formerly belonging to the Caledonian, the LNER has an alternative route through Bathgate. The old Edinburgh and Glasgow main line is the most interesting of the three, even though trains now enter and leave the Glasgow terminus in a normal fashion. The North British locomotive works were situated at Cowlairs, and heavy repairs and re-buildings are still carried out there by the LNER.

Trains from Edinburgh to Glasgow via Bathgate enter Glasgow through an underground line, known locally as the “Low Level” Glasgow, one of the greatest cities in the British Empire, is provided with three underground railways. That of the LNER runs parallel to the Clyde, and forms the southern half of the circular Glasgow City and District Railway. This resembles the London Metropolitan and District lines, but it is worked throughout by steam. A journey through it when traffic is heavy is better as a cure for asthma than as a pleasant experience. Nevertheless it carries a great deal of traffic, main line as well as suburban; and, although clouds of smoke roll up the stairs every time a train enters a station, thousands of people use the “Low Level”. It passes under the Queen Street terminus at right angles to the main lines above.

The LMS also has a “Low Level” underground line, likewise worked by steam traction, though recently trials have been made with a Diesel locomotive. This also runs from east to west, but it is nearer the river than the LNER line, and passes through “Low Level” platforms at the Central Station. Compartment coaches, by the way, are used invariably, as some of the trains travel quite long distances out into the country.

The LMS also has a “Low Level” underground line, likewise worked by steam traction, though recently trials have been made with a Diesel locomotive. This also runs from east to west, but it is nearer the river than the LNER line, and passes through “Low Level” platforms at the Central Station. Compartment coaches, by the way, are used invariably, as some of the trains travel quite long distances out into the country.

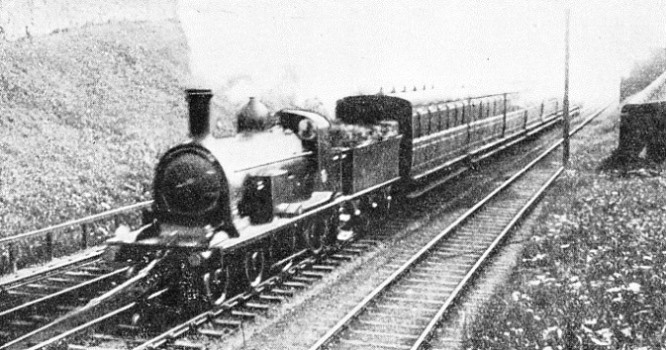

IN THE COUNTRY OF THE GLENS. A London and North Eastern Railway train passing along a stretch of line between the stations of Arisaig and Mallaig.

While on the subject of underground lines, Scotland’s only tube railway, which is known as the Glasgow Subway, cannot be overlooked. This line is the second oldest tube in the world, for it was opened in 1896, being forestalled only by the City and South London Railway. It was formerly operated by cable traction, steam engines in a central power station providing motive power - a quaint but troublesome arrangement. The Glasgow Corporation, who own the line, eventually decided to electrify it, since, in addition to being uneconomical in working, it was an unattractive railway in its old condition, the cars and stations being much inferior to those of the London tubes. The first electric trains began running in the early spring of 1935. Considerable improvements have been made in the stations and in the interior fittings of the cars. The conductor rail is mounted outside the running rails, but there is no centre rail, the running rails completing the circuit as they do on the Southern Railway of England. The Glasgow Subway makes a double track circuit of the City of Glasgow, covering over six and a half miles of route and passing under the Clyde twice. The stations are much nearer the surface than those of the London tubes, lifts and escalators being unnecessary. The Glasgow Subway is the only electric passenger line in Scotland, though there are several electric industrial lines, including the railway at Kinlochleven, in the West Highlands, which connects with the works of the British Aluminium Company.

To return to the main line railways, we must not omit the West Highland line of the LNER. This line runs northwest, along the right bank of the Clyde, then up past Loch Lomond, across the LMS at Crianlarich, and then away over the wild country of Rannoch Moor to Fort William. This is one of the most beautiful railway journeys in the British Isles. From Fort William a more recent extension runs through splendid country to the Inverness-shire port of Mallaig, the farthest outpost of the LNER, and a port of call for the steamers serving Skye and the outer Hebrides. The West Highland line operates but two passenger trains a day, except during the holiday season, when an extra tourist train appears. It is an important link in Scotland’s communications for all that, since over its metals there is an unceasing passage of fish trains from Mallaig. Mallaig exports fish even to North America.

Scottish towns are usually better served than their English sisters in the matter of railway stations. The most important stations in London are not always exactly central, Waterloo lurks in Lambeth, Euston hides behind Bloomsbury, and Paddington is remote indeed. But the two largest stations in Glasgow, Central and St. Enoch, both belonging to the LMS, are right in the middle of the city. So, too, is the LNER terminus at Queen Street. Other Glasgow termini are Buchanan Street (LMS), which is less distinguished in appointments and position, and, on the LNER, Bridgeton Cross, and Hyndland. The two latter serve the trains passing through Queen Street Low Level. They are notable more for the operating convenience they afford than for the number of passengers using them, Queen Street and the through station of Charing Cross taking the lion’s share of the passenger traffic.

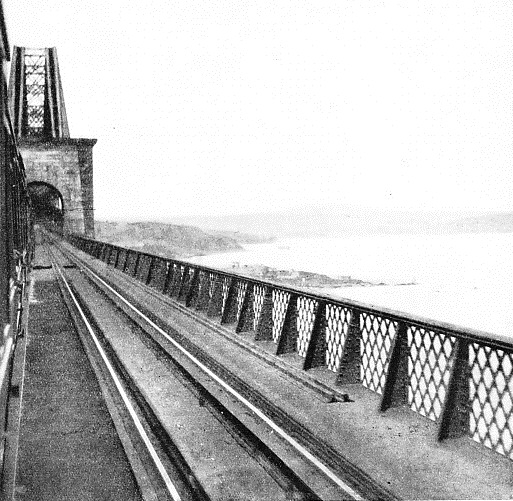

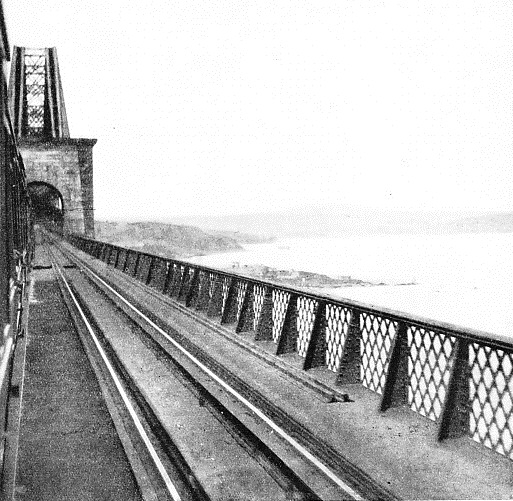

A VIEW FROM THE ABERDEEN EXPRESS as the train crosses the Forth Bridge.

Edinburgh possesses the best placed and third largest station in Great Britain This is the famous Waverley Station of the LNER, situated under the North Bridge in the ravine dividing the Old Town from the New Town. The station contains two terminals, end on to one another, with the station offices between, and with through lines on either side. It covers eighteen acres, and contains nineteen platforms, of which the longest has an overall length of 1, 680 feet. Over 600 trains use it daily. Adjoining the station is the North British Hotel, built by the old company whose name it bears The line enters Waverley from the east, passing under Calton Hill. Westwards it runs through the great ravine below the castle, and passes through a tunnel under the hillock called The Mound. The Mound is now eminently respectable, and the National Gallery stands on it, but once upon a time it was the city’s garbage heap!

The Edinburgh terminus of the LMS is the old Caledonian station at Princes Street. In size and layout it cannot be compared with Waverley, but it is a convenient and well-planned station, with an excellent hotel, and lies in a triangle between Rutland Street and the Lothian Road. Princes Street itself runs off the apex of the triangle. A proposal has been made to replace the two principal stations in Edinburgh by a vast underground Union Station, accommodating buses as well as trains and situated in the middle of the New Town. It is unlikely, however, that this will ever be carried out, as such a station would be badly placed where the Old Town was concerned, and would cost far more than it was worth.

The General Station at Perth is rather fine, though not so well situated as most big Scottish stations. It is a smaller edition of Waverley station at Edinburgh, having the same semi-terminal layout. In addition, a spur bears away from the southern end of the station, where further platforms accommodate passengers for the Dundee line. The Dundee stations, though well-placed, are rather indifferent, but the Joint Station at Aberdeen is a fine building. Here again we find the semi-terminal arrangement, but there are through lines on one side only.

Most curious of all the Scottish stations is that of the LMS at Inverness. The layout is in the form of a triangle, with the base on the north side and the apex pointing southwards. The terminal blocks are in the apex. Trains from the south enter Inverness from an easterly direction, while those going on to the north run out westwards along the shores of Beauly Firth. Local trains enter in the normal way, but the principal expresses run right past the station along the northern side of the triangle, halt beyond it, and then back into the station. Thus a train from the south backs into the northbound platforms, so that the connecting train for Wick and Thurso is alongside it. Inside the triangle are the locomotive repair shops of the LMS Highland Division. In the old days the Highland Railway used to build many of its locomotives at these shops, but engines are no longer built at Inverness.

THE END OF THE RAILWAY in Scotland. This interesting photograph shows a train at Lybster, Caithness, the last station on the Northern Section of the LMS. Lybster is 742½ miles from Euston.

In Scotland, as in England, the earliest railways were completely isolated from one another, and from anything in the nature of a main system. The first Scottish railway was from Kilmarnock to Troon, opened in 1811, horses providing the tractive power. It had its first locomotive in 1817, one built by Stephenson at Killingworth. At first the engine smashed the light cast-iron rails to pieces, but when the engine’s iron wheels had been replaced by wooden ones, all was well. The line was eventually incorporated in the Glasgow and South Western; thus the LMS possesses the oldest stretch of railway in Scotland. The first public passenger line in Scotland was the Monkland and Kirkintilloch Railway, opened in 1826, four years before the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in England, and only a year after the Stockton and Darlington. It must be borne in mind that the Kilmarnock and Troon Railway was a purely private enterprise, and existed simply for the purpose of connecting the Duke of Portland’s collieries with the coast.

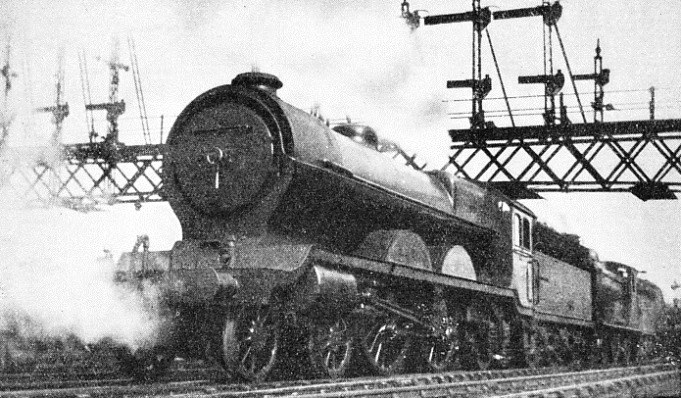

Although, to-day, all the most modern locomotives in Scotland are of English design, the old companies built some very fine machines in their day, many of which are still at work on the most important services. In 1922, the Caledonian had 1,070 locomotives, the Glasgow and South Western had 528, and the Highland 173. The Highland engines were painted green all over, and most of them bore names of Castles, Lochs, Bens, and Clans. Though the LMS has painted them, in common with its other Scottish locomotives, a dismal black, they still keep their names. The North British Railway had 1,074 locomotives, painted in a rather ugly French mustard colour; these included the fine “Atlantics”, together with the well-known “Glen” and “Scott” classes. The Great North of Scotland engines were all small, and only a few had names, but they were well suited to their work. In recent years standard English types have found their way into Scotland, and Mr. Gresley’s splendid new 2-8-2 express engines are being built specially for the Edinburgh-Aberdeen services of the LNER. On the LMS, too, Mr. Stanier’s fine 4-6-0 locomotives, with their taper boilers, are proving exceedingly useful on the Highland main line, where, even now, some of the express engines are of the “Castle” class, a design dating back to 1900. The “Castles” are old engines, but thirty-five years on the best mainline passenger trains speaks very well indeed for their designer, the late Mr. Peter Drummond.

As might be expected with a mountainous country, grand bridges, viaducts and heavy engineering works are common on the Scottish railways, though, curiously enough, there are no long tunnels in the Highlands.

At the present time railway travel in Scotland is comfortable, but, on the whole, slower than in England. This is not the fault of the railway companies. The main lines are very mountainous in places, and the flattest part of the country - the central plain - is dotted with important towns. Another factor, too, is that where there are but two trains a day, as on the Highland and West Highland lines, non-stop running is out of the question. In spite of all these drawbacks, the running generally is very good.

Though the individuality of the Scottish railways has gone, probably for ever, they will always present features unfamiliar to southern eyes. Since they serve some of the most beautiful country in Great Britain, as well as places of great historic interest, they deserve a visit from everyone who can find his way across the Border.

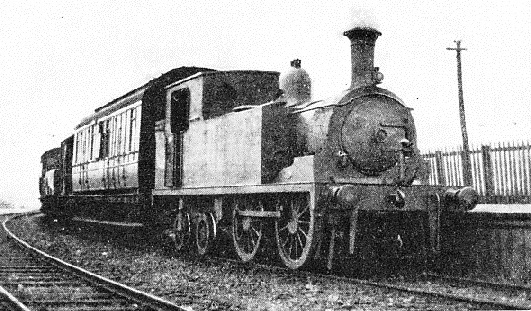

AN OLD NORTH BRITISH TRAIN, assisted by an endless rope, climbing the Cowlairs incline outside Queen Street, Glasgow. To-day heavy trains are banked up the incline by powerful tank engines provided with special slip couplings.

You can read more on “The Forth Bridge”, “A Scottish District Subway” and

“Scottish Mountain Railways” on this website.

The LMS also has a “Low Level” underground line, likewise worked by steam traction, though recently trials have been made with a Diesel locomotive. This also runs from east to west, but it is nearer the river than the LNER line, and passes through “Low Level” platforms at the Central Station. Compartment coaches, by the way, are used invariably, as some of the trains travel quite long distances out into the country.

The LMS also has a “Low Level” underground line, likewise worked by steam traction, though recently trials have been made with a Diesel locomotive. This also runs from east to west, but it is nearer the river than the LNER line, and passes through “Low Level” platforms at the Central Station. Compartment coaches, by the way, are used invariably, as some of the trains travel quite long distances out into the country.