The Influence of the Midland upon Present-Day Practice

RAILWAYS OF BRITAIN - 28

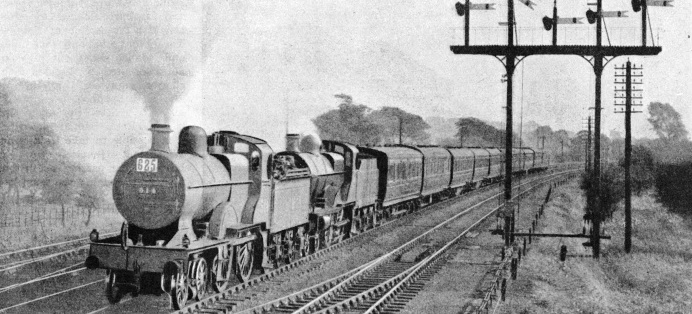

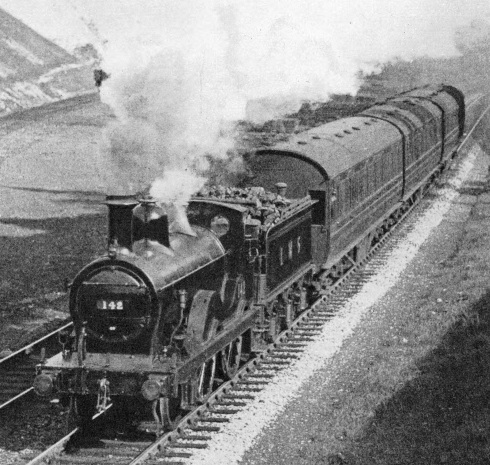

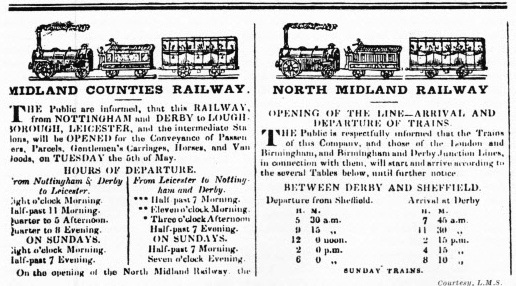

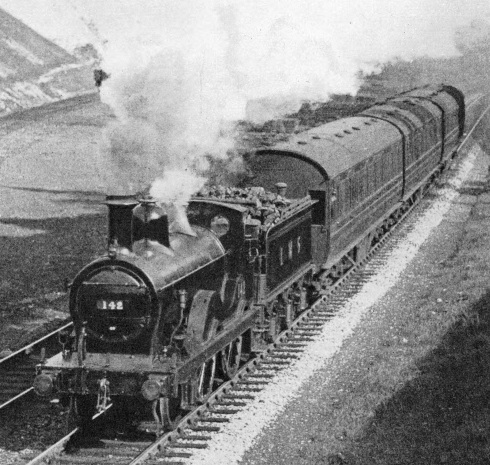

A 4-4-0 LOCOMOTIVE piloting a 4-4-0 compound engine on an LMS “special” between Derby and Manchester. The Midland Railway introduced the 4-4-0 compounds in 1901, and built forty-five. These engines were so successful that the LMS built more, and there are now 235 locomotives of this type in service. The leading engine is of standard “Class 2”, widely used for secondary services.

ONE of the most distinctive of British railway companies lost its identity when the Midland Railway became merged in the LMS in 1923. Nevertheless, a good deal of the Midland influence is still visible. “Midland red” has become the standard colour for all LMS passenger rolling stock, and for the chief LMS express locomotive classes, thus perpetuating the Midland principle of using the same colour for a complete train.

Derby, the hub of the old Midland system, is still an important centre of operation, as it contains the offices of the Divisional Superintendent (Midland Division) and important locomotive works. Both public and working time-tables throughout the LMS are now of the Midland type. Most important of all, alone among the railways forming the LMS, the Midland has retained its name in the heart of the title of the present company, which is London, Midland and Scottish Railway.

Before grouping the original Midland Railway was unique among the larger British railways, in that its own lines failed to reach the sea at any point except at Morecambe and Heysham, until its acquisition of the London, Tilbury, and Southend Railway in 1912. It reached very nearly to the coast at Bristol, and access to various ports and coastal resorts was obtained by means of joint lines in which the Midland had a part interest. Its trains ran to Liverpool over the tracks of the Cheshire Lines Committee, to Bournemouth over the Somerset and Dorset Joint Line from Bath (and a short section of the London and South Western Railway from Broadstone), and to Cromer, Yarmouth, and Lowestoft over the Midland and Great Northern Joint Line. It had also a branch extending as far west as Swansea, an isolated piece of line reached by means of running powers over the Great Western and Neath and Brecon Railways.

The Midland Railway took fourth place among the railways of Great Britain in its route mileage, which amounted in all to 1,529 in 1921; its track mileage in 1921 was 3,223. And the importance of this great system, which extended from London in the south and Bristol and Swansea in the west, to Carlisle in the north and Lincoln in the east, was that it provided a direct link between practically all the biggest centres of population in England. London, Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds, Bradford, Sheffield, Leicester, Nottingham, and Bristol were all on the Midland system. Liverpool was, in effect, on the railway, as the track of the Cheshire Lines Committee which provided access was partly owned by the Midland. Glasgow and Edinburgh were reached by means of through Midland services over the lines of the closely-associated Glasgow and South Western and North British Railways respectively. The Midland’s main line of 310½ miles from London to Carlisle was the longest in Great Britain until the grouping of 1923.

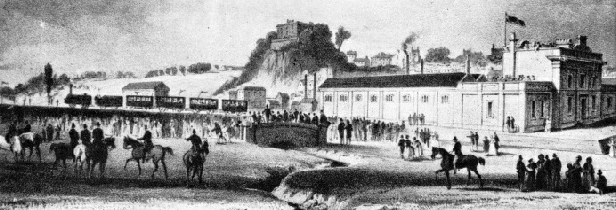

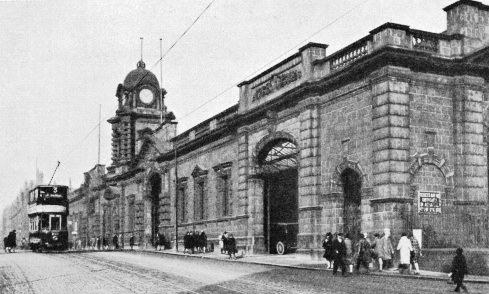

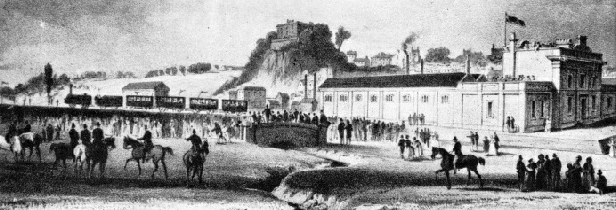

The Midland Railway was formed in 1844 by the amalgamation of the old North Midland, Midland Counties, and Birmingham and Derby Railways. But its system extended no farther south than Rugby, and its first access to the Metropolis was from Leicester by way of Rugby, or via Tamworth and Hampton Junction, and over the London and Birmingham Railway to Euston. Then came the southward extension from Leicester to Bedford and Hitchin, whence the Midland trains made use of Great Northern metals into King’s Cross. This branch still provides the shortest route from Leicester to London, ninety-seven and a half miles in length, as compared with ninety-nine miles to St. Pancras. The final forty-nine and three-quarter miles into the Midland Company’s own London terminus at St. Pancras were opened in 1868.

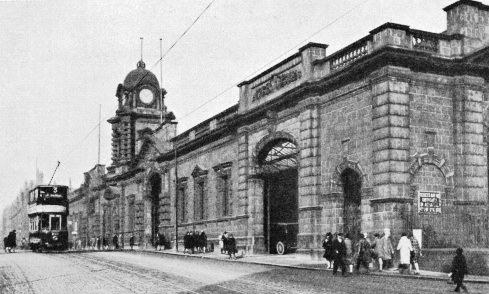

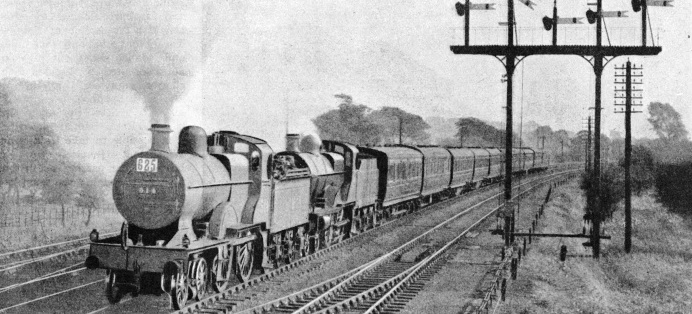

NOTTINGHAM STATION, TO-DAY, an important centre on the Midland Division of the LMS. The down “Thames-Forth Express” covers the 123½ miles between St. Pancras and Nottingham in 129 minutes.

A feature of the Midland system was the extraordinary variety of alternative routes that it offered without any material increase of distance. Out of London, for example, the principal express trains to and from the north divide their attentions between Leicester and Nottingham. The original Leicester route is the more direct, but the loop from Kettering, through Melton Mowbray and Nottingham to Trowell, adds only five and three-quarter miles to the journey Kettering is twenty-seven miles south, and Trowell is twenty-six miles north of Leicester. Then, from Chester-field, the main line through Sheffield, seven-teen and three-quarter miles long, with its steep 1 in 100 climb in either direction up to Bradway Tunnel, can be “by-passed” by the direct sixteen-miles line through Treeton, which is used by certain of the fast services to and from Leeds and beyond.

Trains from London to and from Manchester are not confined to the main line through Derby, Matlock, and Miller’s Dale, with its severe ascent over Peak Forest Summit, 980 ft above sea level. They can travel by the north route to Chesterfield, and thence up the Sheffield line through Bradway Tunnel to Dore South Junction, whence they strike westwards through Totley and Cowburn Tunnels to rejoin the Manchester line at Chinley. This detour adds only four miles, and is much easier, but it is not normally used by London-Manchester expresses. Northwards also from Sheffield, when necessary to relieve the main line between Rotherham and Swinton, it is possible to take trains from Wincobank Junction up the Barnsley line, passing east of that town and rejoining the main line at Cudworth.

A “by-pass” is provided at Leeds, where the Wellington station is terminal, and all Midland trains stopping in Leeds must reverse their direction of running. There is another west of Birmingham, where southbound expresses can avoid the busy New Street Station by travelling direct on the old line from Saltley to King’s Norton through Camp Hill.

All these alternative routes are in regular use; and their value in the event of blockage of a main line, from any cause, needs no emphasis.

NOTTINGHAM STATION, YESTERDAY. This interesting illustration depicts the departure of a train from the city in 1839.

But one of the most ambitious of all the Midland schemes of alternative routing never came to full fruition. The great city of Bradford was, and still is, on no through railway route; the only access to it was by means of branch lines of the late Midland, Great Northern, and Lancashire and Yorkshire Railways. The Midland management, therefore, conceived a costly scheme for a new railway diverging westwards from the Leeds main line near Royston, at a point eighteen miles to the south of Leeds. From here the new track travelled north-westward to the vicinity of Thornhill, where it branched into three. One of these branches made connexion with the main line of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway from Wakefield to Manchester; a second branch, with the help of some heavy earthworks and big bridges, was carried into Huddersfield; the third branch, the prospective Bradford main line, proceeded into Dewsbury. And there it ended, and still ends.

So costly would have been the engineering work between Dewsbury and Shipley, where the Leeds-Carlisle line would have been regained, especially through the city of Bradford, that the remainder of the scheme was dropped. New arrangements were entered into with the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway whereby that company worked through Midland express trains forward from Sheffield to Bradford, by way of the Royston-Thornhill spur, and through coaches off other trains, by the same route, to Huddersfield and Halifax. The “Yorkshireman”, at 4.55 pm from St. Pancras to Bradford, is a descendant of these trains, and there are other similar direct services at 2 pm and 6.15 pm from London. The lines to Huddersfield and Dewsbury, built at such heavy cost, have never been used for other than freight working, and their construction was one of the few British railway schemes of the past that “missed fire”.

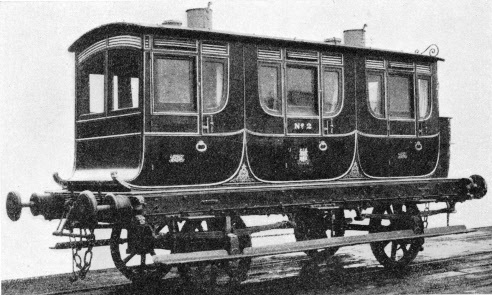

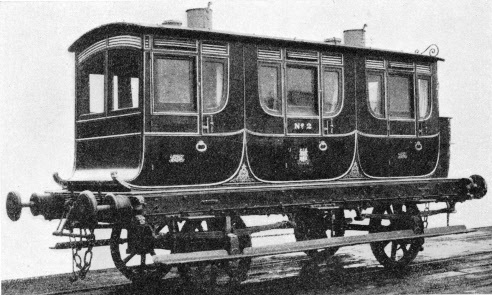

QUEEN ADELAIDE’S COACH, introduced on the London and Birmingham Railway in 1842 for the consort of King William IV. The saloon was built by one of the leading London coach-builders. The London and Birmingham Railway was later incorporated in the LNWR, and finally in the LMS.

Of all sections of the Midland Railway, probably the most expensive in construction was that known as the Settle and Carlisle line. Before it was opened, the only Midland access to Carlisle and the North was from Hellifield by way of Clapham and Ingleton to Low Gill, on the West Coast main line of the then London and North Western Railway, and from Low Gill over Shap Summit. But the connexions at the windswept and isolated Westmorland station of Low Gill were bad, and the North Western showed no disposition to aid its competitor by improving them. The Midland therefore built its own independent route through Appleby, opened in 1875. A little over seventy-one miles of new route were needed and cost £42,000 per mile to complete. The total distance from Hellifield to Carlisle is seventy-six and three-quarter miles.

The location of the line is one of the most interesting in Great Britain. From Settle Junction, three and a quarter miles north of Hellifield, a stiff climb begins up the Ribble Valley, fourteen miles in length, and mostly inclined at 1 in 100, reaching its culmination at Blea Moor. The great limestone peaks of Penyghent (2,273 ft) and Ingleborough (2,373 ft) are prominent here to the east and west of the line respectively. The railway now takes refuge in Blea Moor Tunnel, which is 2,389 yards in length, and thus is carried through into Dentdale, round the head of which the line passes, here fairly level but at a high altitude.

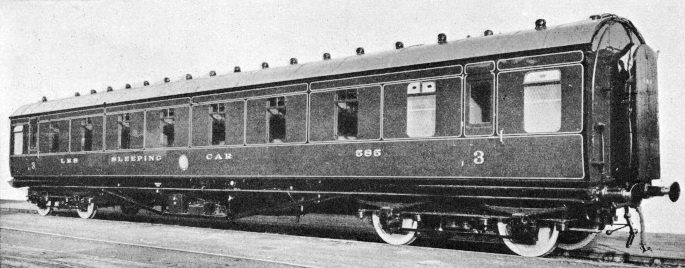

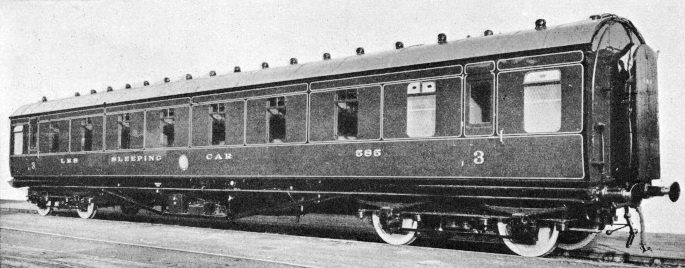

A MODERN SLEEPING CAR. This third-class coach is one of the latest type built for the LMS. Each of the seven compartments has two upper and two lower berths. The capacity is thus twenty-eight persons. Sleeping cars are run on most of the main LMS routes.

Leaving Dentdale, which drains into the Irish Sea, on the west, the railway then tunnels through to the head of Wensleydale, the waters of which run in precisely the opposite direction, and find their way into the North Sea. After passing Garsdale Station, near which there are located the most loftily-situated water-troughs in Great Britain, the line passes through another short tunnel to reach Ais Gill Summit, 1,167 ft above sea-level and the highest altitude reached by any main line in England. It is surpassed by one or two English branches, and by some main lines and branches in Scotland.

From here for forty-eight and a half miles to Carlisle, with a total descent of over 1,100 ft, is a well-known racing ground for northbound expresses, entirely in the watershed of the River Eden, and ultimately through fine scenery as the gorge of that river is skirted past Lazonby and Armathwaite.

Some diminution in the passenger traffic over this line has followed the grouping of the railways. Although the line still affords a useful alternative LMS route to the north, especially for freight traffic, it is questionable if the three millions sterling spent on its construction would ever have been envisaged had the grouping been contemplated at an earlier date. The Ingleton route from Hellifield to Carlisle, referred to above, is only seventy-five miles long and passes over no more than 915 ft maximum altitude, as compared with the seventy-six and three-quarter miles and 1,167 ft the Appleby route.

Frequent Light Expresses

The Midland Railway possessed more long tunnels than any other British railway, including the second longest in Great Britain, Totley Tunnel, between Dore and Grindleford on the Sheffield-Manchester line, 3 miles 950 yards long. On the same route there is also Cowburn Tunnel, 2 miles 182 yards. Between Miller’s Dale and Cheadle Heath, on the Manchester main line, there lie Dove Holes, 1 mile 1,224 yards, and Disley, 2 miles 346 yards. Blea Moor Tunnel, high up in Westmorland, referred to above, is 1 mile 629 yards long, and Bradway, between Chesterfield and Sheffield, 1 mile 267 yards. Incidentally an express from Chesterfield or beyond to Manchester passes in succession through Bradway, Totley, Cowburn, and Disley Tunnels in sucession, making up nine miles of tunnelling in a total distance of no more than thirty miles. Corby and Glaston Tunnels, 1 mile 160 yards and 1 mile 82 yards respectively, are both among the ten tunnels between Kettering and Nottingham. There are four other Midland tunnels just exceeding a mile in length.

Among Midland stations, St. Pancras terminus in London, with its Gothic frontage and its remarkable single-span roof, 243 ft across, covering six platforms and a wide roadway, is the most notable, though Sheffield, with five long through platforms and four “bays”, covers a larger area. Nottingham and Derby also possess handsome stations with five through platforms and additional bays, and the station at Leicester, with its airy all-over roof, is another tribute to Midland station-building enterprise.

AN 0-6-0 LOCOMOTIVE formerly owned by the Midland Railway hauling an LMS freight train near Duffield, Derbyshire, on the line from Derby to Manchester. The Midland used 0-6-0 engines almost exclusively for its freight services. This class is conspicuous for its outside bearings.

In the operation of its trains the Midland worked on the principle of providing fast and frequent service, with the obvious corollary of comparatively light loads. In consequence, no locomotives larger or heavier than 4-4-0’s were used, even up till 1922, for passenger train working, and 0-6-0 engines were exclusively used for freight trains. When traffic was heavy, double-heading of trains, especially in freight working, was rife, and the Midland probably used assisting engines more freely than any other British company. Its best locomotive legacy to the LMS was the three-cylinder 4-4-0 compound design first introduced by Mr. S. W. Johnson in 1901, perfected by his successor, Mr. R. M. Deeley, and built by the Midland to a total of forty-five engines. The type has now been expanded by the LMS to 235 engines, which are at work over all parts of the LMS system from Bristol up to Aberdeen.

On the Midland division of the LMS the locomotive position is now entirely altered. On express passenger services the 4-4-0 compounds and smaller “Class 2” 4-4-0’s soon will be almost entirely replaced by the new 4-6-0 designs, both of the three-cylinder (“5X”) type, with 6 ft 9 in driving wheels, and of the two-cylinder 6 ft mixed traffic type. The latter, however, seem in no degree inferior to the former in the matter of high speed, despite their smaller wheels. Similarly, the heavy coal trains between the Nottinghamshire coalfields and London are now worked chiefly by the thirty-three “Garratt” 2-6-0 + 0-6-2 freight engines, to which previous reference has been made in this work. Each “Garratt” replaces a pair of standard Midland 0-6-0 engines, and is capable of handling trains of from 90 to 100 loaded wagons. On other freight services the widespread introduction of standard LMS 0-8-0 engines has considerably increased the load which can be hauled by each engine, and so has enabled further operating economies to be effected.

Systematic Timings

Another locomotive revolution has taken place on the London, Tilbury and Southend Section, so long the preserve of the famous LT & SR 4-4-2 tanks. Those remarkable engines, despite their limited dimensions, were called on at the rush hours to handle trains of from eleven to thirteen bogie coaches, with practically all seats occupied and so weighing from 330 to 390 tons, on the busy express service between Fenchurch Street terminus and the coast resorts of Leigh, Westcliff, Southend and Thorpe Bay. At last their place has been taken by a stud of powerful new three-cylinder 2-6-4 tank locomotives, and the working of this congested route has been greatly facilitated in consequence.

Some years ago systematic times were adopted for the express trains from St. Pancras. The first trains to be so systematized were the Manchester expresses, which earned the nickname of the “Twenty-Fives”, because their departures were fixed at twenty-five minutes past the even hours, at 2.25, 4.25, 8.25, and 10.25 am, and at 12.25, 2.25, 4.25, and 6.25 pm. Since the grouping, however, the Midland Manchester service has lost some of its former glory, as there is no longer any competition, as in former days, with the London and North Western Railway to stimulate high speed. In those days a St. Pancras-Manchester run was made with only one intermediate stop, at Leicester. In the up direction there were non-stop runs to St. Pancras over the 181¼ miles from Cheadle Heath and over the 169½ miles from Chinley, missing Derby by the avoiding line through Chaddesden Sidings. On the other hand such increasingly important towns on the route as Luton, Bedford, Kettering, Loughborough, and Derby have all benefited by considerably improved train services, as stops have been introduced in many of the schedules previously non-stop. The best Midland London-Manchester times now range round four hours for the 190 miles, or a minute or so less; in the heyday of the Midland-L and NW competition the best Midland time came down to 3 hours 35 minutes - a wonderful achievement over the extremely heavy gradients of this route, though with light loads of five or six coaches only.

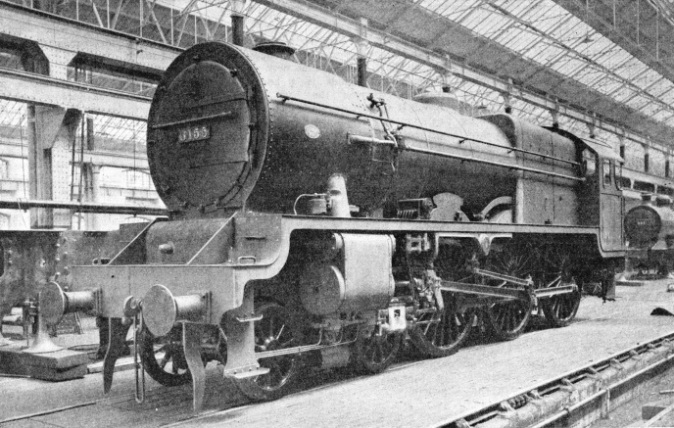

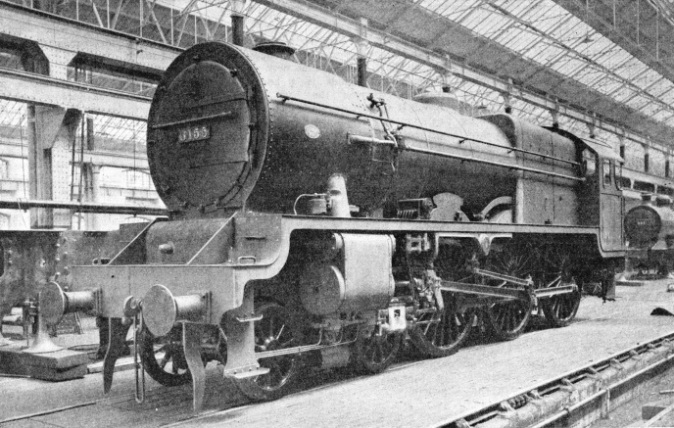

A “ROYAL SCOT” CLASS LOCOMOTIVE at the Derby works of the LMS. The completed engine is seen ready for her trials. Chief dimensions are: three cylinders, 18 in by 26 in; coupled wheels, 6 ft 9 in in diameter; total heating surface, 2,480 sq ft; grate area, 31.2 sq ft; boiler pressure, 250 lb per sq in; and tractive effort, 33,150 lb. Twenty of the first seventy “Royal Scots” were built at Derby.

Similarly, between St. Pancras, Leeds and Carlisle, long before the non-stop Euston-Carlisle run of the “Royal Scot”, over the West Coast main line, had been thought of, the Midland in summer was advertising the 11.50 am express from St. Pancras to run with “no stop south of the Border”. This train, which missed Leeds by the avoiding line from Engine Shed Junction to Holbeck, did make one stop, on Shipley curve, for engine-changing purposes, but this left a daily non-stop run over the 206 miles from St. Pancras.

In the reverse direction, in summer, the up Midland Aberdeen express ran from Leeds to London without a stop. For a short time the schedule was 3 hours 33 minutes, within six minutes of the then best time from Leeds to King’s Cross by the Great Northern route. Now, however, the quickest Midland time between St. Pancras and Leeds is 3 hours 46 minutes, whereas the best by the LNER route has come down to 3 hours 13 minutes. The longest week day run without a stop on the Midland Division is over the 119¾ miles from St. Pancras to Trent Junction by the 6.15 pm down, this being the only train of the day to pass through Leicester Station without stopping. Trains for the north generally leave St. Pancras at the even hours, 9 am for Edinburgh, 10 am for Glasgow, 11 am for Sheffield, 11.50 am (which rather spoils the sequence) for Glasgow, 1 pm for Nottingham, and 2 pm, 3.30 pm (another exception) and 5 pm for Leeds and Bradford, with the “Yorkshireman” at 4.55 pm and the 6.15 pm as additional Bradford expresses.

On leaving the terminus, the engines are faced with adverse grades for most of the first twenty-one miles, not generally steeper than 1 in 176, to a point just beyond St. Albans, with two brief downhill “breathers” included, one to the crossing of the Welsh Harp at Hendon, and the other from Elstree Tunnel down to Radlett. From the summit of the climb at Sandridge there are undulations past Luton until the thirty-fourth mile-post, near Leagrave, which, singularly enough, indicates the source of the River Lea, and not its termination. From here there is a practically unbroken descent, nearly straight and continuously inclined at or about 1 in 200, to the valley of the Ouse at Bedford This bank is greatly favoured by drivers for showing off the paces of their engines, and sustained speeds of over eighty miles an hour are common, with occasional incursions even into the “ninety” realm.

In this connexion it is amusing to recall that at the time of the famous “Race to Edinburgh” in 1888, and the even more famous “Race to Aberdeen” in 1895, nervous old ladies transferred their patronage to what they imagined to be the more sedate Midland Railway, not realizing that the maximum, though not the average, speeds over the Midland at that date were, in general, higher than those reached over either of the competing routes.

Beyond Bedford, which is forty-nine and three-quarter miles from London, and roughly half-way to Leicester, the engines, after taking water from Oakley Troughs, have to tackle the ascent to Sharnbrook Summit, which is the steepest to be met south of Derby. For three miles the line rises at 1 in 119, to mile-post 59¾, which marks the summit, and is dignified in the working time-tables by having passing times of expresses shown against it. The goods lines here are carried on a separate location, and through a tunnel just over a mile in length (the ventilating shafts of which may be seen from the main line), so that the ruling grade against up coal trains may be kept to a maximum steepness of 1 in 200. At Wellingborough, where all four tracks are again on equal terms, blast-furnaces proclaim the fact that we have entered the iron-ore fields of Northamptonshire, and more furnaces are seen at Kettering.

But the most important iron and steel plant in the district is that at Corby, seven and a half miles from Kettering on the Nottingham line, where three million pounds have been spent on development during the last few years.

It is just beyond Kettering that the Leicester and Nottingham lines part company, and the four tracks which have persisted from London come to an end. The Leicester line climbs steeply, partly at 1 in 118 and 1 in 136, to Desborough North, drops at 1 in 132 to Market Harborough, where a speed reduction is enforced round the curve, rises again to Kibworth, and falls to Leicester, with a second slack, over Wigston North Junction. On the up, or southbound journey, the highest speeds may be expected at East Langton (before slowing for Market Har-borough), at Kettering, descending Sharn-brook bank, at Radlett and at Hendon, all of which may provide maxima of 75 to 80 miles an hour, or more. The quickest schedules allow 105 minutes for the 99.1 miles from Leicester to St. Pancras, and seventy-five minutes for the 72.1 miles from Kettering.

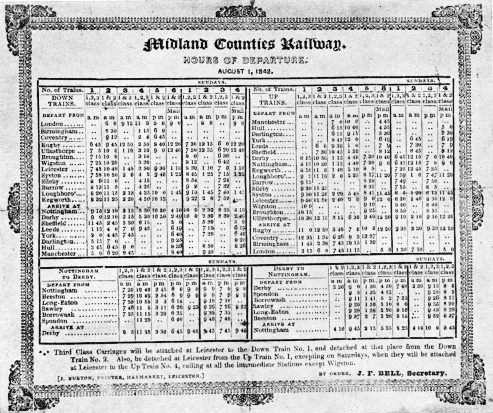

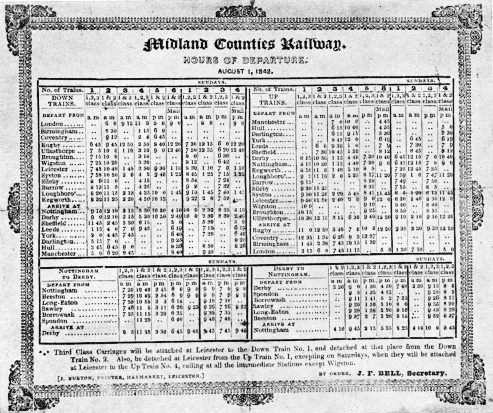

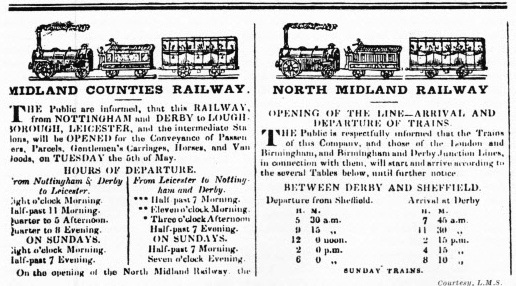

A TIME-TABLE OF 1842. Although this was published two years later than the other Midland Counties time-table shown below, a remarkable advance in style is noticeable.

On the Kettering-Nottingham line, over which the heavy coal traffic is worked from the Nottinghamshire coalfields, the steepest gradient has been kept to 1 in 200. The line climbs to Corby, and then, after passing the steelworks, dives downwards through Glaston Tunnel to the long brick viaduct across the Welland Valley at Harringworth. From here it swings up to Oakham, drops to Melton Mowbray, where speed must be reduced for the curve, climbs to Old Dalby and falls into Nottingham. This was a costly stretch of line to make, with its ten tunnels in the fifty-one miles from Kettering to Nottingham. The best St. Pancras-Nottingham schedule allows 129 minutes for the 123½ miles.

From Wigston, south of Leicester, the track again becomes quadruple, and so continues, with but brief intermissions, all the way to Shipley, north of Leeds. From Leicester to Trent Junction there is one of the rare stretches of level line on the Midland. Trent Junction is a station consisting of one large island platform, in the open country, lying midway between Nottingham and Derby.

Trent Junction was an important railway centre in bygone days, but has now lost most of its former glory. A severe slowing at Trent is succeeded by a long and gradual climb up the Erewash Valley to the summit near Doe Hill, 139½ miles from London. Dropping into Clay Cross, where the junction with the main line from Derby and the West of England necessitates a further slack, expresses bound for Sheffield then make all the speed they can past Chesterfield, with its famous crooked spire, so that the momentum may help them up the arduous 1 in 100 ascent to Bradway Tunnel.

Trains taking the direct line for Rotherham and the North have to reduce speed at Tapton Junction, Chesterfield, whence there is a straight run, mostly downhill, to the junction with the Sheffield loop at Masborough Station. From there throughout to Leeds coal is much in evidence on every hand and no high speeds are possible; and speed must also be severely reduced over the curve through Normanton. The characteristics of the mountainous route on through Settle to Carlisle have already been dealt with.

The Manchester expresses diverge from the Northern route just before Trent Junction, and ten miles farther on are at Derby, where the West of England main line from Bristol and Birmingham is joined. From Derby through the Peak District the Midland route offers one of the most justly-famed railway scenic attractions in Great Britain. At first the line is fairly level, and continues so past Ambergate, with its nearly unique lay-out of three pairs of platforms arranged round a triangle, and under High Tor, at Matlock Bath, to Matlock and Rowsley. Now the climbing steepens past Bakewell to 1 in 100, and tunnel follows tunnel, with wonderful scenic glimpses in between, such as the momentary view of Monsal Dale, to Miller’s Dale, whence there is a final five-miles rise at 1 in 90 to Peak Forest. Limestone is here being turned into lime on an immense scale. From Peak Forest follows an uninterrupted descent, through the lengthy Dove Holes and Disley Tunnels, to Cheadle Heath, outside Stockport, whence a level run of eight miles brings the express into Manchester Central.

On all these routes every Midland express is faced with heavy gradients, and the smartness of the station-to-station timings that have now become standard all over the Midland Division of the LMS is on that account all the more creditable.

A MIDLAND 2-4-0 locomotive still in the service of the LMS. It is seen hauling a slow train between Buxton and Manchester. These engines, which were formerly among the main passenger locomotives of the Midland Railway, are now employed on local services only.

Fast runs are made also on the long West of England branch from Derby to Bristol, over which travel such important cross-country services as the “Pines Express” and the “Devonian”. For forty-one miles the branch pursues a level course through Burton-on-Trent and Tamworth to Birmingham, where the Midland and the London and North Western Railways jointly built the big New Street Station. This still remains practically unaltered, and is now distinctly cramped for the traffic which it has to handle, though in view of its location any extension would be an extremely costly business.

As previously mentioned, it is possible for Midland trains to avoid New Street by taking the Camp Hill route from Saltley to King’s Norton. The exit from New Street, which in either direction is through a tunnel, is as steep as 1 in 80 in the southward direction, and the grades continue for the most part to ascend until the summit-level is reached at Barnt Green. Immediately beyond comes Blackwell, amid the Lickey Hills of Worcestershire, and it is from here that there suddenly drops away, ahead of the train, the famous Lickey Incline, for two miles at 1 in 37.

Bromsgrove is at the foot, and from there on to Cheltenham the engines have a fine racing-ground before them; indeed, certain trains are now booked over the 31.3 miles between Cheltenham and Bromsgrove in thirty-one minutes, start-to-stop.

RAILWAY RELICS OF THE PAST. The opening bills and time-tables of the Midland Counties and North Midland Railways. The former dates from 1840. The Midland Railway itself was formed in 1844 by the amalgamation of these two systems and of the Birmingham and Derby Railway. At that time the Midland had not reached London, its southernmost point being Rugby.

The original line passed through Worcester, but the direct line from Stoke Works to Wadborough, used by the principal expresses, “by-passes” that city, leaving it on the west.

Practically all LMS express trains to the west call at both Cheltenham and Gloucester, connected by a line jointly owned by the LMS and Great Western Railways. South of Gloucester the LMS and the GWR Gloucester-Swindon lines run alongside one another for some distance. At Standish Junction, seven miles from Gloucester, Great Western expresses from Birmingham to Bristol cross over to the LMS tracks, and use them in virtue of “running powers” for twenty miles to Yate, where they diverge on to the GWR South Wales main line.

The most important junction south of Gloucester is Mangotsfield, where the branch line to Bath diverges on the left. Temple Meads Station at Bristol, 130 miles from Derby, is shared with the Great Western Railway.

LEICESTER STATION, now one of the most important junctions on the Midland Division of the LMS. The 99.1 miles between this station and St. Pancras, London, are covered by the best expresses in 105 minutes. Most of the fast trains to and from London stop at Leicester.

You can read more on “The Midland Scotsman”, “The Story of the LMS”, “Three Joint Railways” and “The Waverley Way to the North” on this website.