© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The Midland Railway

The story of the Midland Railway -

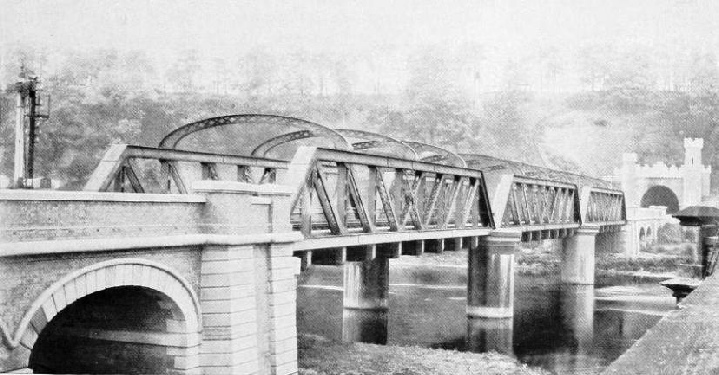

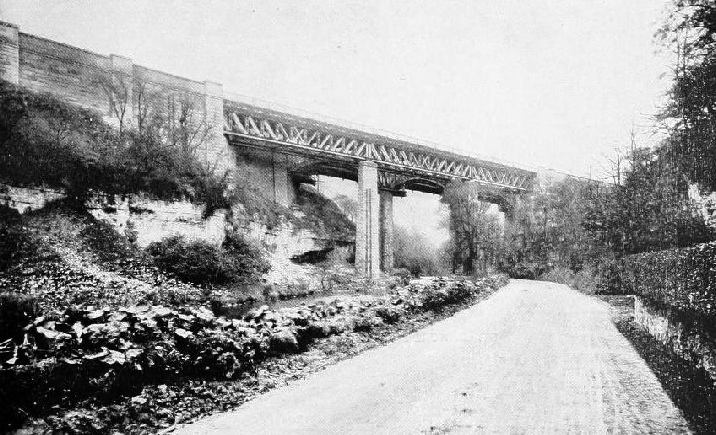

THE TRENT VIADUCT AND REDHILL TUNNEL, showing the castellated portal.

OF the three trunk roads which connect London with Scotland the story of none, perhaps, is so fascinating as that which is known to-

In the early days of the nineteenth century the coalfields of Leicestershire were sorely handicapped by the absence of cheap and expeditious transportation facilities. True there was the Charnwood Forest Canal, extending to the county city, but it was an uncertain highway. ln winter movement was held up by frost and ice, and when the waterway finally burst things were reduced to a critical condition. The city suffered severely from the dearth of fuel, but its loss was trivial in comparison with that of the collieries, which were deprived of their ways and means of disposing of their produce.

It is an ill wind which blows nobody good. Leicestershire’s disaster was the opportunity for the rival coal producing country of Derbyshire and Nottingham. The collieries in the latter county did not let slip the chance to forge ahead, to the detriment of the Leicestershire fields.

This state of affairs became so intolerable that one or two prominent figures in the Leicestershire colliery industry conceived a bold master-

But Ellis was not to be thwarted. He invited the Father of Railways to a bumping dinner, which proved so satisfactory that the eminent inventor was induced to reconsider his refusal. He promised to go over the country with Stenson’s surveys so as to become acquainted with the situation at close quarters. He did so, and reported so favourably upon the project, that he even undertook to raise the money to defray the cost of construction if necessary. As, however, his hands were so full with other plans for railway conquest he pointed out that he could not supervise construction, but strongly recommended that his son, Robert, who had been called home from South America, should be appointed engineer-

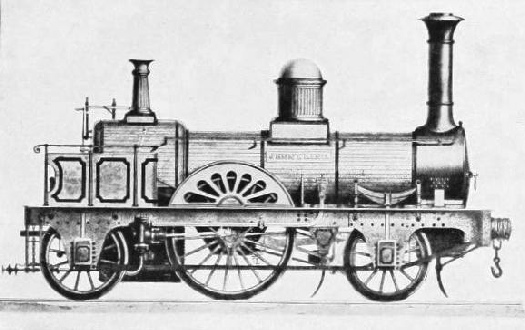

THE “JENNY LIND”. An early type of the single driver locomotive.

Parliamentary sanction for the construction of the Leicester and Swannington Railway, as it was called, was extended in 1830. It was not a big enterprise as railways go, being only sixteen miles in length, but it involved some problems which in those days were by no means so simple to solve as now. The Glenfield Tunnel tripped up the contractors badly. It is perfectly straight, level, and 1,796 yards in length, but it extends through running sand. Boring for a single line of standard gauge was comm-

The opening of this short line solved the coal transportation problem for Leicestershire very effectively, but to the dis-

Another system was the Birmingham and Derby, carried out between these two points by George Stephenson, while the “North Midland” was projected by the same engineer to provide a railway route between Derby and Leeds. In this work Stephenson had a pretty stiff tussle with the treacherous shale when driving the Ambergate Tunnel.

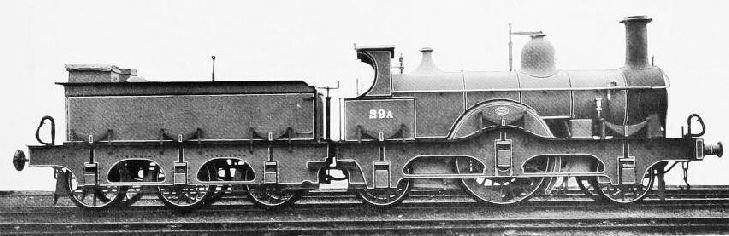

LATER TYPE OF THE “SINGLE DRIVERS”, built June 1865.

The completion of the “North Midland” and the “Derby and Birmingham” lines precipitated a result which was somewhat common in the early railway days, when roads were run to competitive points, and which, while beneficial to the travelling public, affected the shareholders somewhat adversely. Both lines were able to give and take traffic from the London and North Western Railway as it is now. Both fought hard for this business. The competition produced a rate war, with fares and tariffs cut mercilessly. This condition of affairs prevailed until at last, additional competition being threatened from new construction, the rivals awoke to the fact that if further lines were completed the traffic would be divided still more, and they decided that it was better to combine forces. Accordingly a permanent peace was secured in an effective manner -

Then the railway speculating mania broke out with fearful virulence. With it was associated the man who had undertaken the chairmanship of the amalgamated concerns -

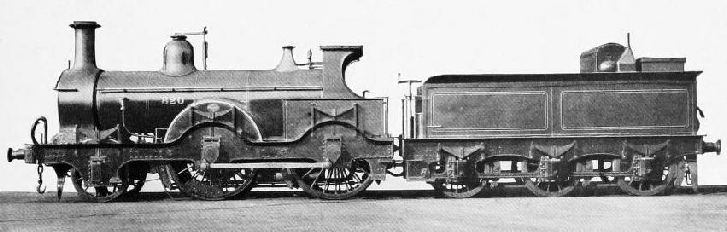

LOCOMOTIVE NO. 820, remarkable for its heavy outside frame.

Although Hudson was assailed when the railway bubble was pricked, in reality he established tin Midland Railway. He had embarked upon a wholesale policy of expansion and absorption, and the outcome was that the system of which he con-

Growing rapidly and prospering immensely, it was not surprising that some curious situations were provoked at times. For instance, the Midland cast covetous eyes upon Manchester. There were two lengths of line lying between Ambergate and “Cottonopolis” which would offer the very means of access to the desired city. Overtures for the acquisition of these two stretches of road were made, but, when all was ready for signing the compact, the London and North Western, having heard of the move, stepped in, offered better terms, and forthwith secured the links, to the discomfiture of its rival.

Foiled in this attempt, the Midland determined more than ever to reach out to Manchester; it would build its own line. Natur-

In forging this link the engineers had to traverse the bleak Peak district, making a tedious climb to a level of 985 feet to reach the summit. This is the country of the dales, and at places the work was heavy and expensive. The driving of the Dove Holes Tunnel, 8,580 feet, was the most trying task. Although extending through limestone, straightforward work was hampered by subterranean streams, which occasioned many anxious moments. On this section, too. a heavy landslide provoked a serious situation. A lofty viaduct had been completed in brick, but the movement played such havoc with the work that it had to be demolished, and a temporary wooden structure run up.

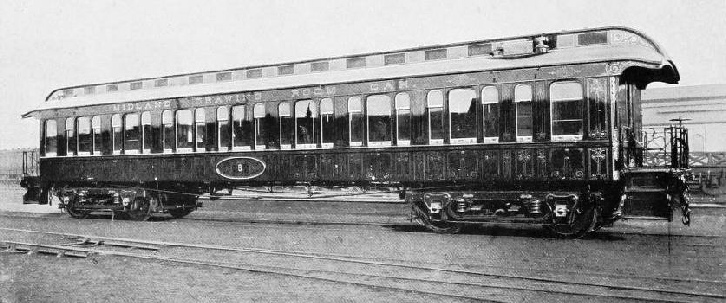

THE AMERICAN TYPE OF PULLMAN CAR WHICH WAS INTRODUCED UPON THE MIDLAND RAILWAY IN 1874. The first vehicle was built at Pullman City (USA), shipped in sections to Derby, and there re-

The Midland, however, suffered most severely in regard to its traffic to and from the South. Rugby was its outpost on the London side. Difficulties, and here all the business was turned over to, or taken from, the London and North Western Rail-

The Midland Railway realised fully its peculiar position, and so decided to secure competition for its southern business. In 1862 it sought powers to build a new line from Leicester, through Kettering and Bedford, to Hitchin, where it could effect a junction with the Great Northern Railway. This offered a shorter haul over a “foreign” line as compared with Rugby, and the London and North Western, recognising that a profitable source of revenue was threatened, fought the project tenaciously, but the promoters had too strong a case, and so won the day hands down. Then a lively bid for Midland business ensued between the Great Northern and the London and North Western Railways, to the benefit of the third party, which now secured a far better service in regard to this class of business than ever had been the case before. It played one line against the other very effectively, but the Great Northern held the stronger position, as the proportion of revenue which had to be paid out by the Midland in this instance was smaller than via Rugby, owing to the shorter haul. In fact the Midland gave the Great Northern Railway so much traffic that the latter line became choked with it. During the course of one year no fewer than 3,100 trains were held up between Hitchin and King’s Cross, the London terminus of the Great Northern, and this despite the fact that the latter line spent over £60,000 in improvements in anticipation of the greater volume of business which it realised must come when the Midland reached Hitchin.

Under such circumstances surprising that the Midland decided that it had better carry its own metals into London, and so reap the full benefits of the traffic. This proposal met with strenuous opposition from the lines already in possession, but here again the case presented was far too overwhelming to enable the opposition to break it down. The Midland proposed, not to proceed southwards from Hitchin, as might have been supposed, but from Bedford through Luton, St. Albans, and Hendon to the metropolis, and this proposal met with approval.

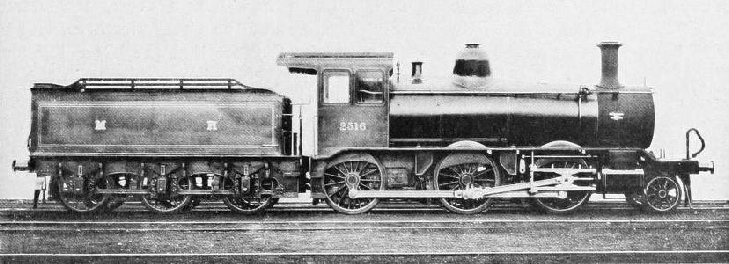

AMERICAN LOCOMOTIVE BUILT IN THE UNITED STATES FOR THE MIDLAND RAILWAY. Although these engines were decried by the British critics they earned their cost in the course of the first year’s service.

The site for the London terminus was the most searching problem in this move. Coming in from the North the line had little scope. A unique opportunity was afforded to build a huge union terminal in the metropolis, similar to those abroad, for the housing of the three lines entering London from the North, but the inter-

In approaching the metropolis the railway was balked by one obstacle. This was the Regent’s Canal, which ran roughly at right angles to the proposed location. The waterway could not be diverted, so the Company was faced with the task either of burrowing beneath or spanning the obstacle. The former would have necessitated placing the terminal underground with a steep approach. Bridging demanded that the platform area should be elevated so as to maintain the gradient. The company decided that the latter was the more satisfactory way out of the difficulty, and it was induced to such a decision by an economic circumstance. The Midland Railway taps Burton-

But the system did not cease its aggressive tactics. Another valuable field awaited exploitation. The traffic of the Midland ramifies to all points of the compass, and the company found that this business was growing rapidly in one particular direction - years before in regard to the London traffic were encountered. An independent line to Carlisle was imperative, so in 1866 a Bill was presented to Parliament seeking permission to bridge the 71¼ miles between Settle and the Border city. Once more strenuous opposition was offered by the line in possession, but once again it proved unavailing.

years before in regard to the London traffic were encountered. An independent line to Carlisle was imperative, so in 1866 a Bill was presented to Parliament seeking permission to bridge the 71¼ miles between Settle and the Border city. Once more strenuous opposition was offered by the line in possession, but once again it proved unavailing.

THE MIDLAND SCOTCH EXPRESS traversing the picturesque country of the dales.

The work on this stretch proved to be among the most difficult experienced in British railway engineering. Ragged crests demanding tunnelling alternated with deep rifts which had to be spanned, and progress was both slow and expensive. Construction came out at over £42,000 per mile, which, although high in comparison with the average of £10,000 to £12,000 per mile in other countries, was about the average prevailing in these islands, so was not so exorbitant as it appears at first sight.

The engineers followed the easiest course that was open to them. Leaving Settle they clung to the Ribble Valley -

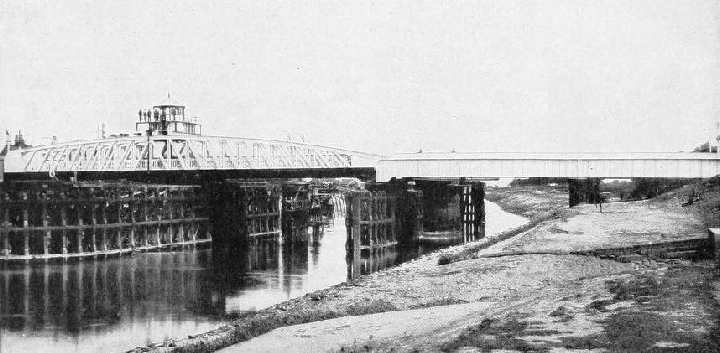

THE SUTTON SWING BRIDGE.

Beyond the summit comes another burrow, the Ruse Hill Tunnel, 1,205 feet long, while 5 miles beyond Hawes Junction, the alignment ran across Aisgill Moor, leading to the borders of Westmorland. Tunnel and viaduct in rapid succession were found unavoidable to reach Kirkby Stephen and Appleby, while some of the cuttings through the spurs attained impressive proportions. While the route extends through rugged country it offers magnificent vistas of the loftiest crests in England, so that the Midland Railway well deserves its colloquial title of “the most picturesque route to Scotland”. By the time the railway builders had bonded Settle to Carlisle over £3.000,000 had been expended. The line was opened fur goods traffic on August 1st, 1875, while nine months later it was available for passengers. From the railway’s point of view the connection was worth every penny which had been laid out. Directly it secured an independent line to the Border city, where a junction was effected with the Scottish trunk roads, its business increased by leaps and bounds. From Bath, its western outpost, to the Scottish border the trains have a clear run of 320 miles, while a continuous line of 308 miles is offered from London to the North. In co-

THE MIDLAND SCOTCH EXPRESS -

But the activity of the Midland has not been confined by any means to the penetration of new territory. The revolutions it has effected in regard to railway operation are equally noteworthy. It was the first to introduce the luxurious Pullman car into this country. Mr (afterwards Sir) James Allport decided to make a bold bid for the London traffic, and thought that the railway coach which had proved so immensely popular in the United States would score an equal success here. Accordingly he ordered a drawing-

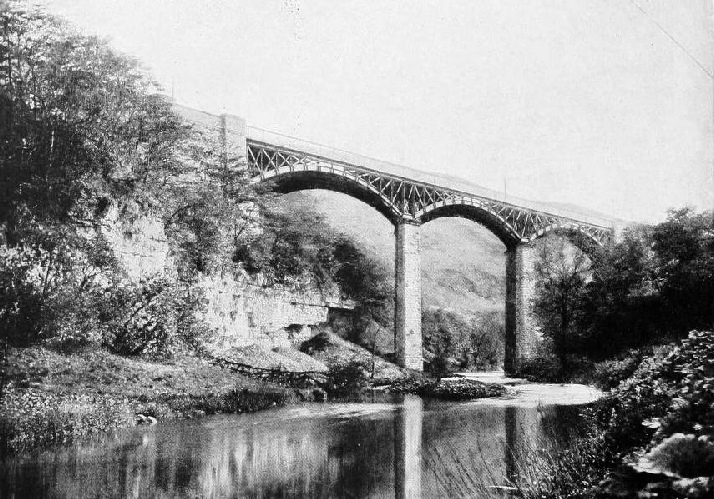

THE FIRST VIADUCT SPANNING MILLER’S DALE, IN 1886.

Gratified with this success, Mr. Allport decided upon another bold stroke. The introduction of the Pullman car had created virtually four fares, as compared with a scale of three upon other systems. To bring the railway which he controlled into line with the other roads he abolished the second class fare. The move was criticised severely, but it proved peculiarly success-

It must also be remembered that the Midland Railway first introduced the popular cheap excursion, and incidentally laid the foundations of the largest tourist travelling business in the world. An energetic citizen of Leicester, Mr. Thomas Cook, realised the fact that if only travel were made more attractive large numbers of people would take advantage of the opportunity, in the same degree that ladies will always flock to a bargain sale. So he approached the secretary of the Midland Counties Railway in 1841 with t he idea of running a special train from Leicester to Loughborough at a cheap fare on the occasion of a temperance congress. Accordingly, on July 5th, 1841, was run the first excursion in railway history, the chance to make the 23 miles round trip for only one shilling proving so irresistible that 570 people took advantage of it.

MILLER’S DALE VIADUCTS, 1905. The growth of traffic demanded a second viaduct, which was built beside the original structure.

The Midland Railway never has departed from its pushing and aggressive policy. Determined to participate in the remunerative Irish trade, it established a new port at Heysham, created its own fleet of steamers, and inaugurated a mail route between London and Belfast. Recently powerful evidences of its activity have been afforded by its acquisition of the London, Tilbury, and Southend Railway, which not only carries its operations into the southeast corner of England, but provides it with a strong hold upon the Thames maritime business. To-

ST. PANCRAS JUNCTION SIGNAL BOX.

[From Parts 17-

You can read more on “Britain’s Inland System”, “The Midland Scotsman” and “The Story of the LMS” on this website.