© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The Railway Mania

George Hudson and the Railway Mania

EVERY now and then a nation loses its head over financial matters, goes money-

We all know something of the famous South Sea Bubble, which in Queen Anne’s reign ruined thousands of thrifty folk, and left behind it many a desolated home and suicide’s grave. Hundred pound shares of the South Sea Company’s stock changed hands for a thousand pounds or more. Then the reaction set in; the shares fell in value with terrible rapidity, and soon were worth little more than the paper of the scrip. It took all Walpole’s financial genius to save the credit of the nation from being lost amid the general catastrophe.

Even more disastrous in its consequences was the mania for buying and selling shares in existing or projected railways which twice seized the British public; the first time in 1836, and again in the years 1843-

In the early thirties the railway had few friends. Those people who were not openly hostile to it, were either utterly indifferent to its development or cynical. As a few years ago caricaturists heaped ridicule on the motor car -

But in spite of the jeering the faithful few persevered, and the despised railways soon began to pay dividends of 10 and even 15 per cent. In 1836 money was “easy”, that is, plentiful, and profitable investments were hard to find. So that before long the railways attracted the attention of the financial world. People suddenly discovered that the earning of a good dividend covered a multitude of sins. The iron track, once everybody’s butt, blossomed into “a great civilizer”, “a priceless boon”, “a triumph of peace”, and so on, according to the command of language enjoyed by the journalist who rushed into print in praise of the new panacea for all evils social and political.

Folk tumbled over one another in their eagerness to buy scrip. The wildest schemes for new lines found immediate support. Nothing seemed too idiotic, when the public had for the time become a race of idiots; among whom only a few men, such as George Stephenson, managed to keep a cool head. Huge fortunes were made and lost in a week or two. Paupers became rich men; millionaires sank into poverty. Trickery and knavery of all sorts was rampant. The industrial balance of the country was upset; and the year ended amid the gloom of acute monetary depression.

Yet the speculation of 1836 was but a mild gamble compared with that of the second period (1843-

As during the cycle “mania” of some years ago, everything and everybody connected with the cycle trade enjoyed a sudden “boom”, so during the furore of 1843-

The surveyors also showed a sad lack of manners, being attracted on the one hand by the rewards accruing from business successfully carried through, and encouraged on the other by the wealthy companies for whom they worked. Collecting bands of ruffians, they set the landowners at defiance, with the natural result that there were some very pretty scuffles, when the owners also organised a force to resist the invaders.

By 1845 the rage of speculation had become so acute that the police had often to be called in to regulate the crowds besieging the Stock Exchanges of London and other large cities. Amid the general rush for money the railway did, indeed, to some extent prove a leveller, for people of all classes jostled one another in their haste to purchase the scrip dangled temptingly before their eyes by this or that promoter. Vainly did sober journals, such as the Times, urge caution and self-

Meanwhile the Parliamentary horse was being worked to death. Five hundred and sixty-

Then ensued such a scene as cannot be paralleled in the history of finance. The boom was already showing signs of a break, and it became absolutely necessary for such schemes as should be saved from ruin to be given Parliamentary powers to commence work at once. November 30 happened to be a Sunday, and this led to some difficulties. Never was the first day of the week less a day of rest. At twelve o’clock the offices of the Board of Trade would be closed.

Promoters hired special trains, special coaches, or special relays of horses to bear their plans to the Metropolis. In some cases a railway refused to carry people interested in a scheme that might prove harmful to it, and all sorts of devices were resorted to to evade the officials. A story is told of a large roll of plans being placed in a coffin, which was taken to the station on a hearse, attended by mourners wearing all the outward signs of deep sorrow. The coffin, on reaching London, was driven straight to the Board of Trade Offices, where its contents found their last resting-

Post-

Of course, many plans arrived too late, and the bearers, driven to desperation, hurled them in through the windows, from which they were as speedily ejected.

Of course, many plans arrived too late, and the bearers, driven to desperation, hurled them in through the windows, from which they were as speedily ejected.

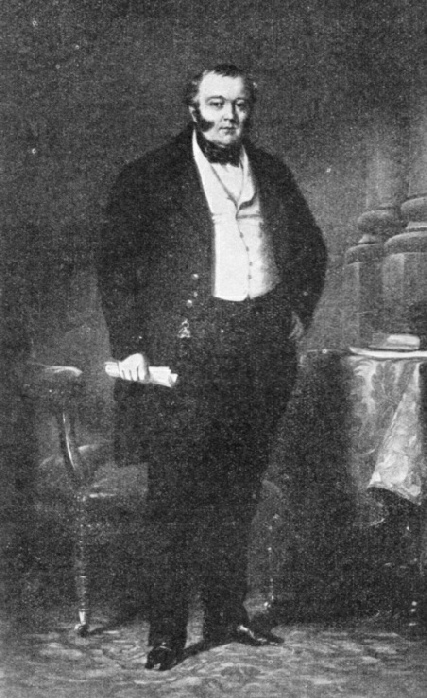

“THE RAILWAY KING” George Hudson, a great financier of the nineteenth century, whose story is linked with that of the LNER. He spent £3,000 a day in legal fees when fighting rival companies.

Then came the crash. Prices fell by leaps and bounds. Everybody wished to sell, nobody to buy. Thousands found them-

Among the speculators of those wild days no one could vie with the “Railway King”, as George Hudson was named. He may be called the Napoleon of the mania, for although he outgeneralled his opponents, won many brilliant victories, and had the financial world at his feet, he eventually found his Waterloo. It must be placed to his credit that even if, after the manner of conquerors, he caused a great deal of misery, he did some really good work in the cause of railway extension, notably as regards the Midland system, of which he was the first Chairman.

Born in 1800, he began life as a linen-

During the mania Mr. Hudson fought a fierce Parliamentary battle on behalf of the Midland against the proposed London and York scheme. As a fighter he was seen at his best, -

Whether intentionally or not, Hudson became involved in transactions that savoured of fraud, and in 1846, at a meeting of the Midland Board called for the purpose of deciding whether they should buy up the Leeds and Bradford line recently opened, he was openly accused of consulting his own interests rather than those of the shareholders whom he represented: because, as Chairman of the Leeds and Bradford, he had advocated the purchase of that line by the Midland. Though he apparently cleared himself from the charges of misappropriation, his reputation had received a blow from which it never recovered.

The “Railway King” now fell on evil times. He whom the Prince Consort had once asked to be introduced to him, became the target at which every caricaturist launched his shaft. It was vain for him to state: “It has been my good or bad fortune to be the purchaser of many railways; and I might frequently have taken advantage of my position and knowledge to go into the market and lay out large sums with great benefit to myself, but I publicly declare that I have not done so, and call upon any person who can prove anything to the contrary to come forward and do it at once.” Satirists delighted to recall his draper days, and represented him sitting in his shop; at the mouth of a tunnel learning “how a great deal of railway business may be kept in the dark”; or seated in spider shape at the centre of a huge railway web to catch the shareholders for whom he had spun the meshes. Last scene of all, George Hudson, alone and deserted on a platform, vainly trying to stop the train which was leaving him in the lurch.

At an extraordinary meeting of the Midland shareholders held at Derby, April 19, 1849, Mr. Hudson, in a letter of considerable length, stated: “After due deliberation I have thought it right and to be more satisfactory to the shareholders of the Midland Railway Company to resign the office of chairman.” The thousand proprietors there assembled also found his action most satisfactory, and his connection with the Midland was thus severed. He had undoubtedly been playing a double game which an honourable man could not have reconciled with his conscience. He had, while professing undivided loyalty to the Midland, taken a share in obtaining Parliamentary sanction for a short line which, by connecting the Great Northern with the Manchester and Leeds Railway, deflected on to the metals of the former company a large amount of traffic hitherto handled by the Midland. When this was discovered -

Till the last he retained his self-

This brief account of the man to whose piping the railways of England danced for nearly a couple of decades may fitly be closed with the words of Mr. Clement E. Stretton, who says: “The greatness of Hudson’s railway genius only makes it all the more lamentable that so great a man should have so deplorably fallen and have been guilty of acts which resulted in ruin and universal condemnation.” [The History of the Midland Railway, p.268.]

You can read more on “The Atmospheric Railway”, “London’s First Railways” and “When Railways Were New” on this website.