Through Running of LMS Rolling Stock Over Other Railway Systems

FAMOUS TRAINS - 42

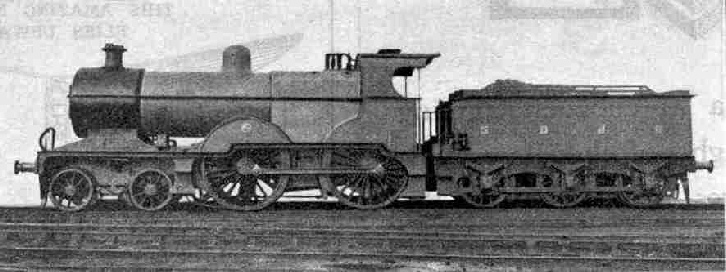

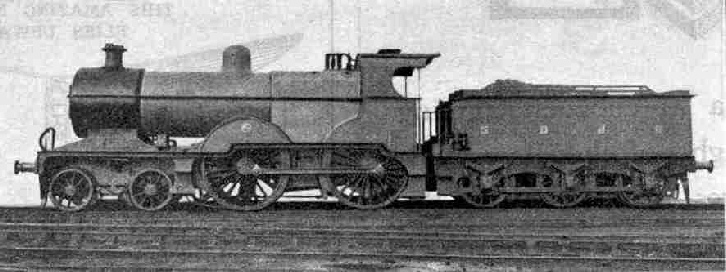

Locomotive No. 70, 4-4-0 type, Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway.

PERHAPS the most singular thing about such a title as the “Pines Express” of the London Midland and Scottish Railway is that the pines are not “L.M.S. pines” at all! It may seem equally strange to see “The Devonian” running over L.M.S. metals when that company owns not a yard of track in Devonshire. Through running of L.M.S. rolling stock over the systems of other railways solves the puzzle, however. The Great Western Railway sees to it that “The Devonian is safely deposited in due course on the South Devon coast, and the Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway similarly takes charge of the “Pines Express” at Bath and brings it at last within sight and smell of the pine-woods of Bournemouth, the final stage of the journey being over the metals of the Southern.

If you look at a railway map of England you will see that the ramified L.M.S. system extends one great tentacle southward and westward from Birmingham, into the heart of Great Western territory, as far as Bristol, where the two companies jointly occupy the Temple Meads Station, to which we travelled in one of the two-hour expresses from London last month. This is the route followed by “The Devonian” from Bradford and Leeds to Torquay. Branching southward from this main line at Mangotsfield, near Bristol, a short spur runs into Bath, where one station is again used by two companies - the one-time Midland and now L.M.S., and the Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway. The Somerset and Dorset Railway, when in a bad financial position, was taken over jointly by the Midland and London and South Western Railways, away back in 1875, the principal object being to give the Midland direct access to Bournemouth. Now, of course, it is jointly owned by the L.M.S. and Southern Railway but, like the Midland and Great Northern Joint, it is the proud possessor of its own locomotives and rolling stock. So it is to the care of a royal blue Somerset and Dorset locomotive that the Midland red L.M.S. engine hands over the “Pines Express” on arrival at Bath.

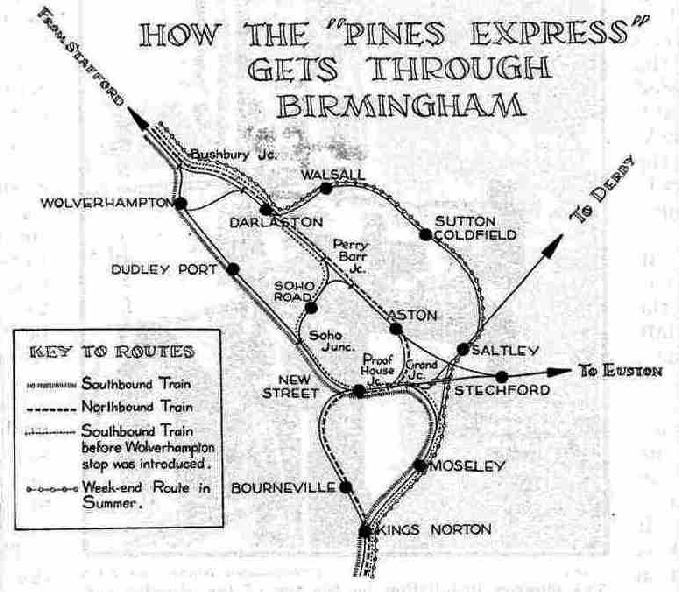

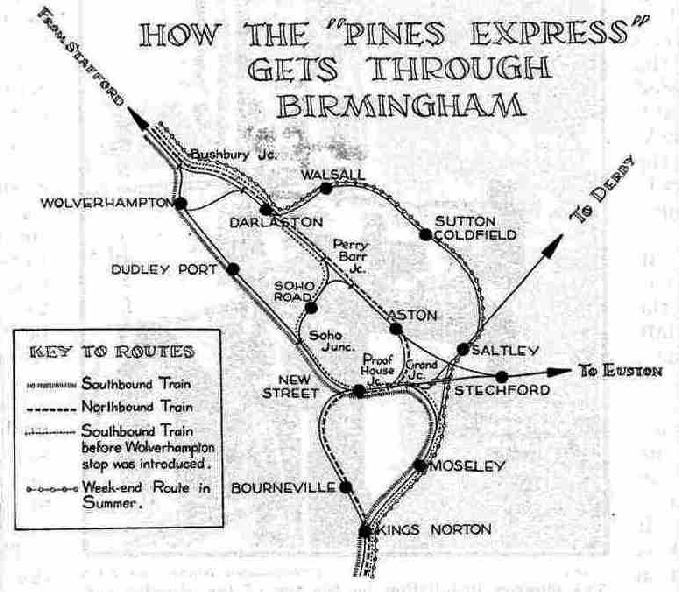

In the course of its long journey from Liverpool and Manchester to Bournemouth, the “Pines Express” does some curious things. It was first instituted by the London and North Western and Midland Railways in conjunction, the former bringing it down as far as Birmingham, where it was handed over to the latter. ln exactly the same manner it is now handed over from the Western to the Midland Division, and is in this way the only regular passenger train that crosses from one set of tracks to the other outside the great New Street Station. Apart from this, it is the only daily express that is worked by the Western Division from Birmingham away to the North out of the opposite end of New Street, as though it were off to London. This has the remarkable result that, whether you are travelling to Bournemouth or from Bournemouth, in either case you run out of the east end of New Street, and yet without any reversal of the train!

Again, as it leaves Wolverhampton out in the cold when going north, it is the only daily express to run over the short length of line connecting the Portobello and Bushbury Junctions just outside that town. At summer week-ends the “Pines Express” gives the great city of Birmingham the “go-by” too, running round a much more extraordinary route through Walsall and Sutton Coldfield on to the main line from Derby, and then by the connecting spur up to King’s Norton, where the West of England main line of the Western Division is joined. Over this route it is the only express train ever seen.

A word or two now as to the composition of the train. The main section of it, including the ubiquitous restaurant cars, works through between Manchester (London Road) and Bournemouth. In pre-grouping days this was Midland stock, and the restaurant cars only ran between Birmingham and Bournemouth; the Midland Division still finds the coaches and the cars, hut the latter complete the whole journey in each direction. So far as through working is concerned, Liverpool has to be content with one through “composite” for Bournemouth, but this is strengthened by a four-coach corridor set for Birmingham, as the “Pines Express” provides the fastest service of the day from both Liverpool and Manchester to the great Midland city and back, and is correspondingly popular.

There is one more coach in the Liverpool section, and that is destined for Southampton. The “Pines Express” carries it as far as Cheltenham, where it is detached in order to work over the one-time Midland and South Western Junction Railway through Swindon to Andover, and thence over the Southern to Southampton. In the grouping the M. & S.W.J.R, which was previously an independent company, became the property of the Great Western Railway, and the G.W.R. therefore advertises itself in the formation of the “Pines Express” by providing its own Liverpool-Southampton coach, the gay cream and umber livery striking a brilliant note on the tail of the long procession of Midland red vehicles. When the whole train is assembled, between Crewe and Birmingham, it is therefore very heavy, seldom consisting of less than 14 corridor vehicles, though the proportion of the total journey over which this loading prevails is fortunately short.

It is at 9.40 a.m. that the Liverpool portion of the “Pines Express” is due to leave Lime Street, just ahead of the 9.45 a.m. “Merseyside Express” from Liverpool to London. It is, of course, much pleasanter to be going to the seaside than to be coming away from it, so that naturally we patronise the southbound train; though, truth to tell, we are but a few miles away from the Irish sea when thus we make our start for the English Channel. Up the tremendously deep rock cutting, varied by a remarkable succession of short tunnels, we mount at 1 in 93 over the route of the original Liverpool and Manchester Railway until we reach Edge Hill. A brief stop, and we are away again at 9.46 a.m, threading our way through the maze of junctions between here and Wavertree, which need to be seen on a plan in order that their complexity may be properly appreciated. We also pass the great Edge Hill concentration sidings, which were among the very first in the country to be laid out for marshalling by gravity.

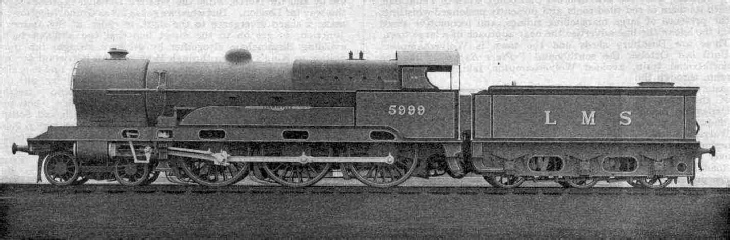

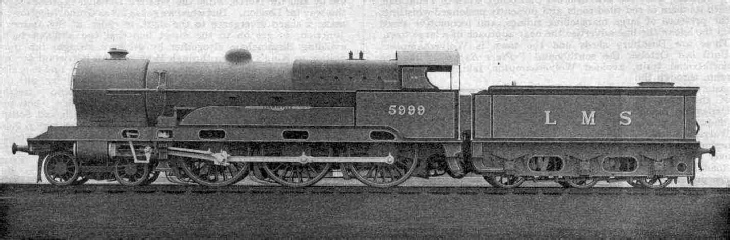

No. 5999 “ Vindictive”, one of the re-boilered “Claughtons” fitted with the original Walschaerts Gear.

In the ordinary course we do not travel far before the next stop, as the train is booked to call at the Liverpool suburban station of Mossley Hill, if required, to pick up any passengers for Birmingham and beyond. Very few of the expresses so booked to make a “conditional” stop at Mossley Hill ever fail to do so; even the proud “Merseyside Express” almost always makes its first halt, on the non-stop journey from Euston to Liverpool, at this station, so bringing to an end the longest all-the-year-round non-stop run on the L.M.S. system, 189¾ miles in length.

The next stop after leaving Mossley Hill at 9.52 a.m. is at Crewe, where we are to meet and be attached to the Manchester portion of the train. There are four tracks as far as Ditton Junction, and we gather speed on the falling grades from Speke to Ditton, taking water at full speed from the track-troughs close to Halebank Station. At Ditton Junction, on the left of the line, we see the large creosoting works at which the major portion of the sleepers used in relay ling on the Northern part of the L.M.S. Western Division are creosoted, and then “chaired”, preparatory to laying. Enormous stacks of sleepers in course of seasoning are the chief means of attracting the attention of the passer-by to the depot.

We have now to cross the biggest engineering work that we shall see on the whole route. When the Manchester Ship Canal was cut through from the estuary of the Mersey to “Cottonopolis”, to give ocean-going steamers direct access to that city, the five main lines of railway crossing its route could not have their traffic interrupted by swing-bridges, which would enable the steamers to get by. The Ship Canal Company therefore had to raise each line to a height sufficient to clear the steamers passing underneath, involving very high embankments and the big bridges that may be seen at Irlam and Partington on the Cheshire Lines system (we crossed the latter in February with the L.N.E.R. “North Country Continental”); then the L.M.S. bridges at Latchford and Acton Grange (the second carrying the West Coast main line) near Warrington, and now here between Ditton and Runcorn.

Of these five bridges Runcorn is the biggest. We bear to the right after Ditton Junction, mounting a high embankment, on to a brick viaduct as we circle round the great chemical works established here, and last of all passing on to the bridge itself This consists of three lattice girder spans, each 305 ft across, carrying the track 75 ft above the water level. The Ship Canal is crossed just before we get to the opposite side. The view from the bridge is very extensive. On the left the Runcorn transporter bridge and the smoky chimneys of Widnes monopolise most of the foreground, but on the right any clear day will enable you to see the mountains of Wales in the far distance.

There is further climbing from Runcorn until we reach the summit at Sutton Weaver, whence we fall until we bear to the right to effect a “flying junction” with the main line from the North, at Weaver Junction. A high viaduct carries us over the River Weaver; next we hurry through the salt country, round Winsford; and presently we are running past the east side of the great Crewe locomotive works. Here we note the remarkable suspension bridge, with its enormous span over the tracks at the north end of Crewe station, which gives access to the works from the platforms, ere we come to rest at 10.34 a.m. We have run the 32 miles from Mossley Hill in 42 minutes.

The Manchester portion, which has left London Road at 10 a.m. and called at Stockport, makes the level 25-mile run from the latter town in half-an-hour, and follows us in at 10.40 a.m. When all the marshalling has been done, we are, or should be, ready to leave for the south at 10.47 a.m. The “Merseyside Express” has rolled in before we leave, at 10.40 a.m, with its “Royal Scot” at the head. As far as Birmingham our engine is one of the four-cylinder 4-6-0 “Claughtons”, and it is not unlikely that we may enjoy the services of one of the latest large-boilered “re-builds”, of the type illustrated above.

If we have as many its 14 coaches out of Crewe, the total weight behind the tender will be, in all probability, a little over 400 tons, perhaps 420 or so. The going will be heavy up to Whitmore, there being three miles rising at 1 in 177 from Betley Road to Madeley; but having completed the 10½ miles to the summit point in 16 or 17 minutes, we shall cover the next 14 miles to Stafford in “even time”, passing the latter in just over the even half-hour. Water is taken from the track-troughs at Whitmore, which are the last that we shall see in the course of this journey. Trains for the Birmingham direction at Stafford have the advantage over the London expresses that they do not have to reduce speed at Trent Valley Junction. The earliest route from London to Stafford and the North was, of course, by the London and Birmingham Railway to Birmingham, and on from there; the Trent Valley line from Rugby to Stafford through Nuneaton, Tamworth and Lichfield was made at a considerably later date.

We hurry past the beautiful old Shropshire town of Penkridge, with its mass of red-tiled roofs, and presently prolonged whistling, the presence of large marshalling sidings, and locomotive sheds on the left of the line advertise the near approach of a large town. These are Bushbury sheds and the town is Wolverhampton. Until last October the southbound “Pines Express”, like the northbound train, avoided Wolverhampton, taking the original route through the eastern outskirts of the town to Darlaston, Bescot (midway between Walsall and Wednesbury), and then over the Soho Road spur on to the present main line again, so to reach New Street. But now we diverge to the right at Bushbury, sweep up the incline over the Great Western Birmingham and Chester main line, with a fine view of the Oxley engine-sheds, and so into the High Level station at Wolverhampton. The 39¾ miles from Crewe here are allowed 50 minutes, and we are due at 11.37 a.m, for a stop of three minutes.

Over the next 13 miles of the journey the veil is best drawn. It is through the heart of the “Black Country”, and black it is, in very truth! Iron and steel articles in vast quantities are made in the area bounded by Wolverhampton and Birmingham in the one direction, and Dudley and Walsall in the other. For example, fully 90 per cent, of the galvanised steel chair-screws used by British railways, to the tune of millions every year - and they are no “pocket” screws, either, as each one weighs just over 1½ pounds - are made within a radius of three miles from where we are running at the moment, just south of Wolverhampton, Blast-furnaces are seen on every hand, but most of them, unfortunately, have gone out of use, other districts, such as Tees-side in Yorkshire, being for various reasons able to produce the iron more cheaply. Dudley Castle is seen on the hill away on the right, as we run through Dudley Port. Finally, after passing through a very smoky tunnel, which is an awkward bottle-neck at this end of New Street Station, we run into the latter, 20 minutes after leaving Wolverhampton, at precisely 12 noon. Here our “Claughton” is detached, together with the four-coach corridor “set” that has come down from Liverpool, and replaced by a Midland 4-4-0 or, if the train is sufficiently heavy, with two.

As mentioned earlier, we are going to leave New Street in the “wrong” direction altogether for Bournemouth, as departures of Midland Division trains from this end of the station are for Derby and the North, while the Western Division expresses leave this way for London. But when we get as far as Grand Junction we make a sharp divergence to the right, in order, at St. Andrew’s Junction, to get on to the direct line that the Midland built, avoiding Birmingham altogether by giving a straight run from Saltley to King’s Norton through Moseley. An important service of Birmingham suburban trains runs round this way, and it is also used by all the Midland freight traffic between North and South, which is thus kept out of New Street; but our southbound “Pines Express” is the only fast train making regular use of this route. After mounting some heavy gradients we join at King’s Norton the main line that has come out of New Street by Selly Oak and Bournville - where Cadbury’s great chocolate works is situated - having in this way completely reversed our direction of running. We left New Street at 12.8 p.m, and are due to pass King’s Norton at 12.22 p.m. Beyond here we notice the recently-completed widening of this main line.

After running a bare seven miles farther, despite the fact that all signals are off we are brought momentarily to a dead stand at a station called Blackwell, at 12.32 p.m. We have reached the head of the famous Lickey incline, which is for two miles inclined at the formidable figure of 1 in 37¾. All trains, whether passenger or freight, are compelled to halt there, the former to test the brakes and see that they are in proper working order, and the latter to pin down sufficient of the wagon brakes to ensure a safe descent. Acceleration after starting is, of course, tremendously rapid, and our driver has to apply his brakes frequently in order to keep the train under proper control. The incline is, however, almost perfectly straight from top to bottom.

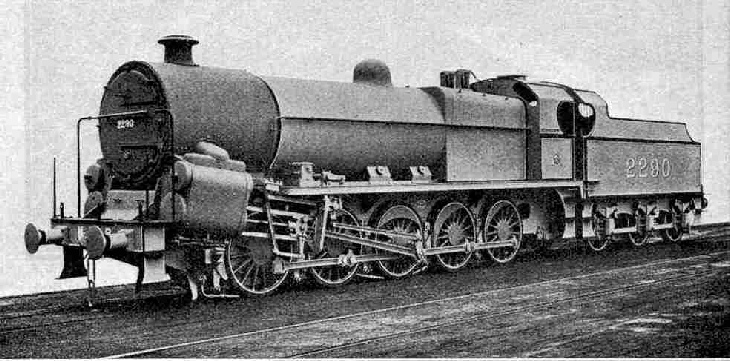

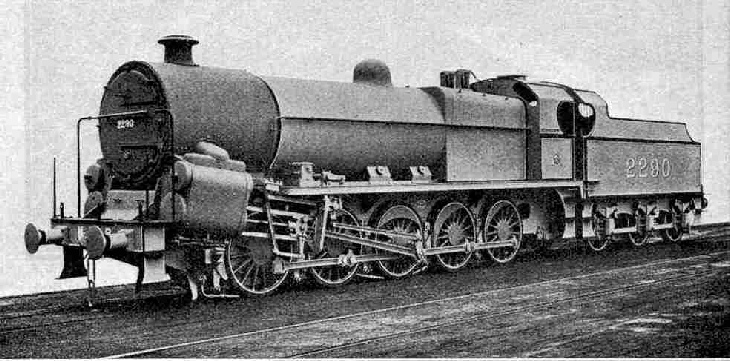

At the foot lies the station of Bromsgrove, and here we should keep a sharp lookout to the right, in order to see in the sidings the only ten-wheel locomotive in the British Isles. No. 2290 - the “Lickey Banker” - was built by the Midland authorities at Derby for the sole purpose of banking trains up this two-mile incline. Every northbound train has to stop at Bromsgrove for assistance and, in the case of passenger or freight trains of any weight, two 0-6-0 tank engines, coupled together, perform the banking duty. No. 2290, which has four cylinders 16¼-in diameter by 28-in stroke, and 10-coupled wheels, undertakes the same duty single-handed. It is probable that for so very short a run a tank engine design would have been employed, as in the Great Eastern Railway “Decapod” of 1903, were it not considered that side-tanks and a coal bunker on the main frames would have made No. 2290 too heavy for the track.

The next 25 miles, to just beyond Ashchurch, form a fine “galloping ground”, mostly either level or slightly downhill; and over this length we should maintain an average rate of a little more than a mile a minute. From Stoke Junction, two miles from Bromsgrove, to Abbot’s Wood Junction, near Worcester, we run over a direct line avoiding the latter city, which is distinguished by affording the longest continuous stretch of track without any intermediate station that is to be found in the British Isles - the 14½ miles from Bromsgrove to Wadborough. So we hurry down the valley of the Severn though not actually seeing the river - through Defford, Bredon and Ashchurch, where the line from Evesham to Tewkesbury makes, with our main line, one of the rare level crossings of one railway over another that are to be found in this country. Soon after passing Cleeve we shut off steam, and at 1.13 p.m. we pull up at Cheltenham Spa. The 47¼ miles from Birmingham have taken us 65 minutes, and the 31 miles from Bromsgrove 36 minutes.

The famous “Lickey Banker”, No. 2290, built by the Midland authorities at Derby for banking trains up the two-mile Lickey incline.

From Cheltenham it is but a short run of 6½ miles to Gloucester, allowed 10 minutes. All expresses over the West of England line of the L.M.S. stop at both places, except during the height of the summer. Just after we leave the Lansdown Station at Cheltenham, the Great Western Railway comes in on the left, and from there to Gloucester the trains of both companies run over the same joint metals. These trains include the Birmingham and Bristol expresses of the G.W.R, which run along the same track as the L.M.S. Birmingham-Bristol trains as far as the Engine Shed Junction at Gloucester. They avoid that city, but presently are seen travelling alongside the L.M.S. lines again to Standish Junction, near Stonehouse, where they transfer on to the L.M.S. line over which we shall presently run, and follow it for 20 miles to Yate. Here they pass round a connecting spur on to the Badminton line of the G.W.R. at Westerleigh. using that into the same station at Bristol Temple Meads as the L.M.S. expresses, in the reverse direction of that by which we travelled to Paddington last month by the 5.15 p.m. up two-hour Bristol express. But this is a digression.

We reach Gloucester at 1.28 and leave at 1.36 p.m. For a long distance the Cotswold Hills rise like a great rampart on our left hand, and the lulls of the Forest of Dean are seen across the Severn Valley on the right. There are some sharply rising grades out of Gloucester, partly at 1 in 104 and 108, to Standish, seven miles away, for most of which distance, as previously mentioned, the Great Western line from Gloucester to Swindon and Paddington runs alongside. Not infrequently, too, the trains of both companies are seen doing a thrilling “neck-and-neck” along here. The next 10 miles are mostly failing, and then there is a rise for 7½ miles past Charfield and Wickwar; but the gradients in both cases are mostly moderate, between 1 in 250 and 300. At Mangotsfield North Junction, 31½ miles from Gloucester, which we pass at 2.17 p.m, we slow severely to diverge from the Bristol main line on to the Bath branch. Presently we find ourselves in the Avon valley, with Brunel’s old main line from London to Bristol by Bath on the right, and at 2.31 p.m. we draw up in Queen’s Square Station at Bath, having covered the 41 miles from Gloucester in 55 minutes.

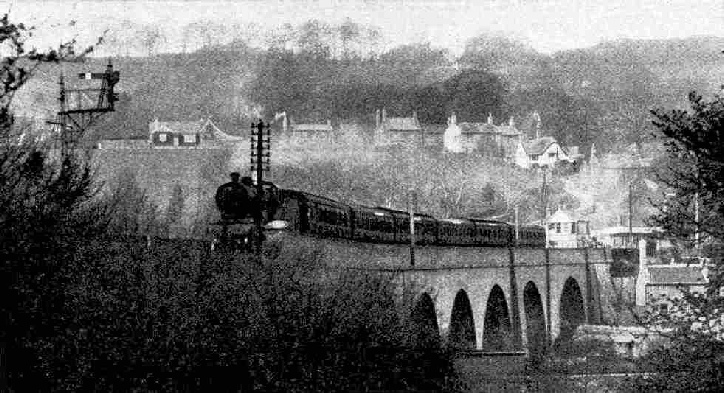

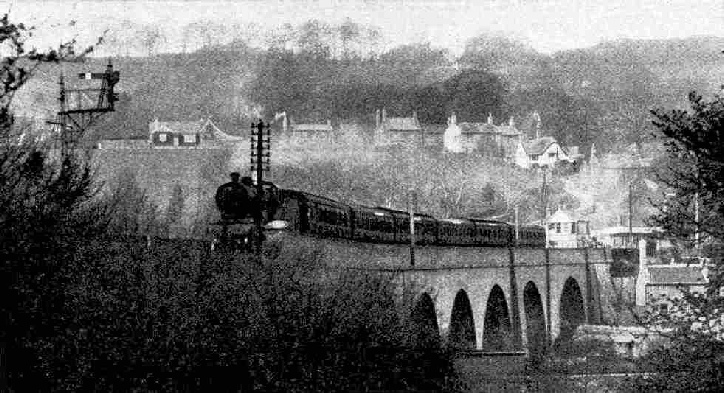

The “Pines Express” crossing Midford Viaduct, Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway.

Queen Square Station is terminal, so that the blue Somerset and Dorset locomotive that is to complete the journey of the “Pines Express” comes on at the other end of the train. It is of the 4 4-0 type, built, like most of the recent engines of this railway, at the Derby works of the L.M.S, and conforming almost exactly in type and appearance to the Midland “Class 2” engines. In view of the tremendous gradients over which we are about to travel, it is singular that the S. & D.J. management have never adopted any more powerful design for their passenger work. The Midland compounds have been tried over the route and, still more singular, Derby has built for hauling coal trains over the S. & D. more powerful locomotives - of the 2-8-0, or “Consolidation” type - than any ever built for its own Midland freight services. Be that as it may, our engine is not allowed to tackle more than 185 tare tons without assistance, and the chances are that, if our train still exceeds six coaches, unless some light stock m the formation brings seven within this limit, we shall have to take a pilot locomotive to the summit at “18¼ miles”, between Binegar and Masbury. This pilot probably will be a 0-6-0 freighter of the standard L.M.S. type (of which the S. & D. owns a number) fitted with the passenger brake for mixed traffic working.

Directly we are past Bath Junction and on to the single line, the gradient begins. There are no half-measures about it, either; it begins at 1 in 80 and soon steepens to 1 in 50! We rise over the Great Western main line and presently enter Devonshire Tunnel. Shut your carriage windows here and pity the unfortunate crews on the engines, who are having no enviable task in the suffocating atmosphere produced by two hard-worked engines in the narrow confines of this single-line bore, although it is fortunately short. At 2½ miles out of Bath the grade changes, and the engines have some respite; for over a mile of the distance this is through Coombe Down Tunnel. At Midford we pass on to double line again and at Radstock, 10½ miles out, we find we are passing through the heart of the Somersetshire coalfield, the pitheads looking singularly out of place amidst such lovely country. Climbing now recommences in earnest. Altogether some eight miles at between 1 in 50 and 80 have to be faced, until we attain the crest of the Mendips just before Masbury, where, if we have taken a pilot, we make a brief stop for it to come off the train. Re-starting, a swift downhill run, with brake applications where necessary on the 1 in 50, of which, on this side, there are over five miles in continuous lengths brings us to Shepton Mallet. For the 21¾ miles from Bath to this point 42 minutes may seem a generous allowance, but the gradients make it fully necessary. Still descending, we make the short run of 4¾ miles to Evercreech Junction in eight minutes, or probably less, reaching there at 3.26 p.m.

The “Pines Express” at Templecombe No. 2 Junction, Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway.

The next stretch of line is still double, and for the 10½ miles to Templecombe, sharply undulating, the timetable allows 15 minutes. Between Evercreech and Cole we cross the Westbury main line of the Great Western and then, diverging to the right at the Lower Junction at Templecombe, we run up into the main station there, alongside the West of England main line of the Southern. Getting away from Templecombe is a curious business, as we have to back on the Somerset and Dorset line again, at “No. 1” Junction, before we can proceed with our journey. Then we carry on to the southward, travelling over the single line from there to Blandford at a surprisingly high speed - often for miles continuously at well over 50 miles an hour - and taking the passing-places without any reduction of speed, as they are smoothly laid out and equipped for the automatic exchange of the single-line tokens. Stalbridge and Blandford are passed, and we are now in Dorset.

At Corfe Mullen Junction we branch rightward from the Wimborne line, climb over the ridge and drop to Broadstone Junction, with severe slacks at both junctions. Presently the big expanse of salt water in Poole Harbour comes into view, and at Holes Bay we run on to the main line of the Southern between Bournemouth and Weymouth, over which we travelled with “The Thirties” three months ago. Poole is reached at 4.35 p.m. We are on the final stage, and it is a steep one, part of the climb past Parkstone being at 1 in 60. The “Pines Express” is now at last within sight of the pines, and the tonic of their smell carries our locomotive over the summit at Branksome, whence we drop gently down the steep incline into Bournemouth West Station.

The time is 4.46 p.m. - at least it ought to be if we are punctual - and thus we have taken six minutes over seven hours on our long journey from Liverpool.

Bath Station, L.M.S. The “Pines Express” is nearly ready for departure.

You can read more about “The Atlantic Coast Express”, “Cross Country Routes”, and “Three Joint Railways” on this website.