Express Trains Operated by the Great Western Railway

FAMOUS TRAINS - 41

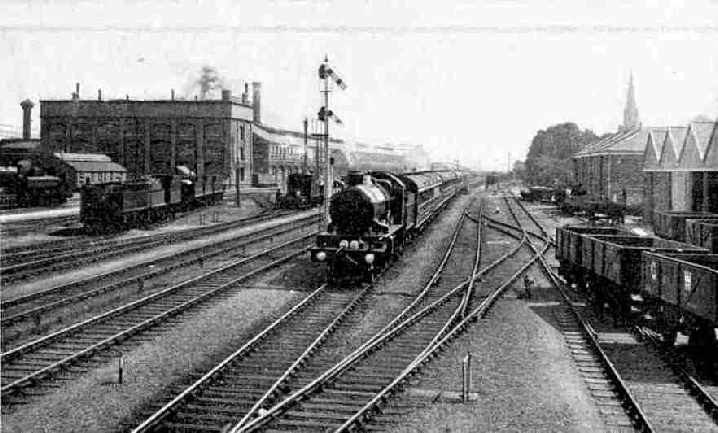

We make a rapid start over the first mile or so out of Paddington. “King” Class 4-6-0 locomotive, No. 6007, “King William III” passing West London Junction.

THROUGHOUT their history the Great Western Railway Company have taken a leading part in the development of rapid travel in Great Britain. For many years past the locomotive authorities at Swindon have laid themselves out to produce engines capable of maintaining high speeds over long distances continuously, and the traffic authorities, with these locomotives at their command, began, about a quarter of a century ago, to embark on a deliberate policy of bringing the West of England nearer to London. On other railways acceleration has often been the result of competition, but without any such spur (except as regards Exeter and Plymouth in the West, and Birmingham and other important towns in the North) the Great Western have speeded up their train services in every direction, until now they lay claim to most of the premier places in the table of fastest runs performed daily in the British isles.

The train service by which we are to travel this month occupies some specially high places in this list. To reach Bristol in two hours from Paddington, as is done by two trains daily, entails an average speed of 59.2 miles per hour, for the distance covered is 118.3 miles by the Bath route. The Badminton route, used by the two up two-hour expresses, is only a shade shorter, and the average in this case is 58.8 miles per hour. But still more remarkable is the fact that both of the two down expresses mentioned - the 11.15 a.m. and the 1.15 p.m. out of Paddington - carry on the rear slip portions for Bath, which are booked to be deposited in the station of the famous spa exactly If hours after starting. The distance from Paddington to Bath is only a fraction under 107 miles, so that for over 100 miles of their journeys each of these expresses has to travel at an average rate of 61.1 miles per hour. Similarly on the up journey, the allowance made by the timetable for running the 100 miles from Badminton to London, pass to stop, is only 95 minutes, the average rate required in this case being 63.2 miles per hour.

Right from the beginning the Great Western line was intended to be a speed line, and was laid oat accordingly. Favoured by the nature of the intervening country, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, its first and probably its most famous engineer, carried his track up the Thames Valley nearly to Didcot, and then struck across level country to Swindon, whence he was able to drop into the valley of the Bristol Avon, near Bath, ere he emerged on the shores of the Bristol Channel, and pursued its left bank for the best part of the way to Taunton. The fall into the Avon Valley made necessary the only appreciable gradients in the whole of this distance of over 150 miles - at 1 in 100 for 1½ miles between Wootton Bassett and Dauntsey, and chiefly at the same grade for miles through the Box Tunnel, which in its turn is the chief engineering work on the route. The Great Western is the only level main line out of London, taking its course up the river valley instead of having to rise in order to make its exit over the ring of hills that encircles London both north and south.

There could hardly be a more extraordinary contrast between two railway routes than there is between the one over which we travelled last month and that of this month. The “Engadine Express” finished its journey over gradients stiffening finally to 1 in 40 and 1 in 29, in long stretches; the Bristol two-hour trains, on the down journey, have to face nothing steeper than 1 in 660 against the engine, and for a large part of the journey the “ruling”, or steepest gradient, is 1 in 1,320, or one foot rise every quarter-mile! It is singular to notice, however - and the fact quite apparent when one is taking accurate record of the speeds - that even 1 in 1,320 makes an appreciable difference in the speed when the train is travelling fast, up to a maximum variation of perhaps five miles per hour, according to whether this modest inclination is “up” or “down”.

The “Engadine Express” carried us up to an altitude of 6,000 ft above the sea; the highest part of the Bath route from London to Bristol is not more than a couple of hundred feet above Paddington, with some 70 miles in which to overcome this trilling difference m level; though the Badminton route, used by the up two-hour trains, certainly goes over a greater altitude.

The Great Western main line from Paddington to the West of England via Bristol is a striking example of considering the gradients too much at the expense of distance. Brunel by avoiding the hills, made his main routes so circuitous that in more recent years the London and South Western built a line shorter by 22½ miles to Exeter; while the London and Birmingham Railway, later absorbed in the London and North Western, was 16¼ miles shorter than the Great Western route, which diverged from the West of England main line at Didcot, and then turned northward through Oxford, Banbury and Leamington. Since the beginning of the present century, therefore, the Great Western management, to remove the stigma of having the letters “G.W.R.” interpreted as the “Great Way Round”, and to recover traffic that was being lost to their shorter and quicker rivals, have been compelled to spend large sums of money with a view to cutting the corners off their main routes.

From 1901 onward, indeed, a total of 160 miles of cut-off routes have been opened in various directions - the Westbury route to the West of England, the High Wycombe route to Birmingham and, among others, the Badminton route to South Wales, over practically the whole length of which we travel on our up two-hour journey from Bristol to Paddington. All the original lines planned by Brunel are still earning important traffic, however, and on our down journey to Bristol we travel throughout over Brunel’s earliest route, on which the only changes of note have been that certain important stations - such as Reading - have been entirely rebuilt and rearranged, while the “Broad Gauge” track that Brunel laid, with 7 ft between the running faces of the rails, has inevitably given place to out standard figure of 4 ft 8½-in. The only present reminder of the Broad Gauge is seen in the distance between the up and down lines at many points, especially at stations, where the outside rails were left in their original position, in order that it might not be necessary to shift the platforms, while the inside rails were closed up by the difference between the two gauges, which involves a “six-foot” of proportionately increased width. The Great Western are the only British railway company that can place their signals, when they desire to do so, with their posts between the up and down tracks of a double line.

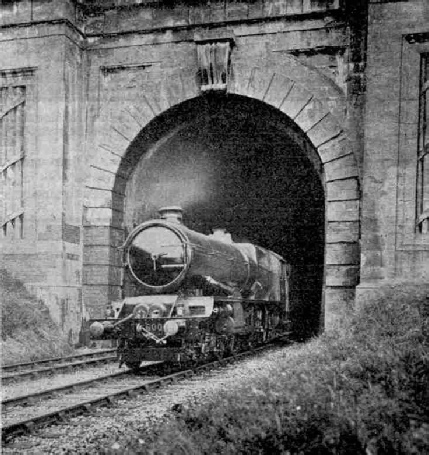

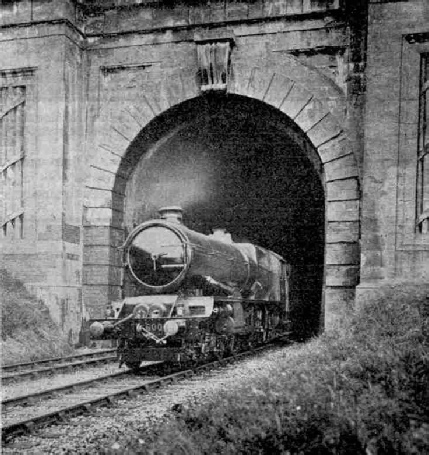

Bristol Two-hour Express emerging from Box Tunnel, near Bath, hauled by 4-cylinder 4-6-0 locomotive No. 6000 “King George V ”.

Another reminder of Brunel’s day may be seen in some of the sidings by the side of the line, which are still laid as he always laid his track, with what are called “bridge” rails fastened down to longitudinal sleepers, in their turn kept at the correct distance apart by wrought iron tie-bars. In comparison with journeys over other lines, travellers of this period always maintained that running over the Great Western had no superior anywhere. Whether this was mainly due to the Broad Gauge, or to Brunel’s methods of track laying, has never been satisfactorily settled.

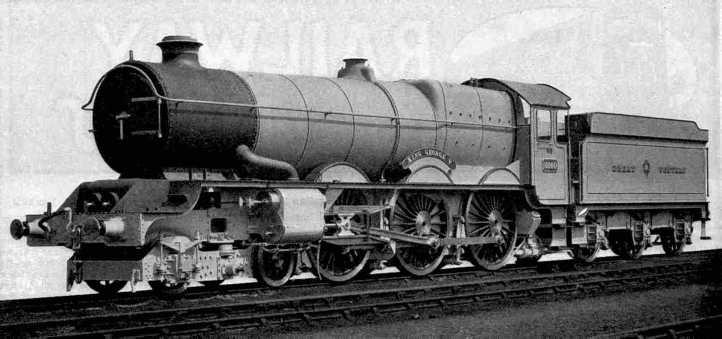

It is now time that we began to think of our journey. In accordance with the sensible principle of systematic train departures that is now standard on the Great Western and Southern systems, we find that trains for the Bristol direction leave Paddington at 15 minutes past the hour. The two down two-hour trains make their exit at 11.15 a.m. and 1.15 p.m. Both of them, as we have seen, carry slip portions for Bath, which are labelled “Bath Spa Express”, and the 11.15 a.m. has a further “slip” for Didcot, often consisting of three or even four coaches, because, of the extraordinary number and diversity of the connections that it makes in different directions at Didcot. So, although the 1.15 p.m. seldom takes out of London, except on Saturdays, more than six or seven coaches, the 11.15 a.m. may be relied on to carry at least 11, with a total load, including passengers and luggage, of 370 to 375 tons for the first 53 miles of the journey. It is for this reason that the latter is now a booked turn for one of the latest four-cylinder 4-6-0 locomotives of the “King” class; and we shall, of course, make this the train of our choice for the run to Bristol.

The formation of the 11.15 down remains fairly constant. Throughout the winter the main, or Weston-super-Mare portion consists of five of the latest 60 ft steel-panelled corridor coaches, with a 70ft restaurant car in the centre, the whole set having an empty weight of 195 tons. Next follows the Bath slip portion, which will probably be a couple of big 34-ton 70 ft composite corridor - that is to say, provided with a corridor along the coach, but not vestibuled to the train ahead. The Great Western authorities have never favoured the vestibuled type of slip coach that was used for a time before the war on the Midland and London and North Western Railways, allowing the use of the restaurant car until just before the slip was detached. Behind the Bath slip is the Didcot slip - a composite slip brake coach followed, usually, by a couple of “thirds”. After being dropped off at Didcot, this portion of 85 or 90 tons’ weight is worked through to Oxford. The Bath slip coaches, however, are simply taken over to the opposite side of the station, and just over an hour after their arrival are on the way back to Paddington by the 2.7 p.m. express from Bath, due in London at 4.5 p.m.

As far as Swindon we travelled over this route before on the “Fishguard Boat Express”, so that little need be said about the first part of the journey. After the manner almost invariably followed by the drivers of express engines working at high pressures, we make a rapid start over the first mile out of Paddington, leaving the platform at somewhere near the full cut-off of 75 per cent. By Acton or Ealing the engine has been well notched up to 20 per cent, or even 15 per cent cut-off, and we accelerate more slowly; but by Southall, or shortly afterward, we cross the “60” line, and on passing Slough we should be not far off 70 miles an hour. The engine can carry on indefinitely at round about 70 miles an hour, even with so substantial a train as this, over the beautifully level line that Brunel has left the Great Western as his most notable legacy. Unless we have experienced signal or permanent way delays, however, too vigorous a progression may carry us more ahead of time than is advisable, and in that event the driver will “ease” the engine, and we shall drop down to 65 miles per hour or so. In the normal course we should get through Slough, 18½ miles from Paddington, in about 21 minutes; Reading, 36 miles, in 37 or 38 minutes; and Didcot, 53 miles out, should be cleared in just about “even time” - that is, 53 minutes from the start.

The tender water supply has been replenished from Goring troughs, between Reading and Didcot. Craning our heads out of the window as we approach Didcot - a most indefensible practice, but we really can’t help it in the circumstances! - we see the three Didcot coaches quietly drop off the rear as we dash through the station at 65 miles an hour or more. We notice standing here, too, the train that has left Paddington at 10.45 a.m, which we are booked to pass at Didcot; and we may be sure that the Didcot slip carried at least one or two passengers for Swindon or the Gloucester line who have saved half-an-hour by taking the later train, and overtaking their rightful train in this ingenious way. It is not a “booked” connection, but it is usually “safer” enough to tempt not a few, as it has done me before now when I have been on the way to Swindon.

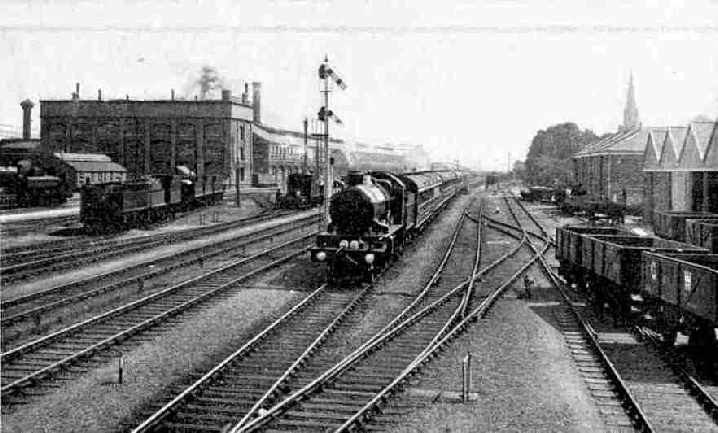

The gradients, if such they can rightfully be called, now steepen slightly against the engine, although at no point steeper than 1 in 660, which is 8 ft rising in the mile. This may pull the speed down very slightly, but with our train now reduced to 280 tons, the powerful “King” at the head of it will have no difficulty in keeping the speed just above the mile-a-minute rate. Threading our way at speed through the big yards at Swindon, therefore, we ought to pass there in very little over 75 minutes from the start. The scheduled passing time is 12.32 p.m, and at exactly the same moment the up two-hour express that leaves Bristol at 11.45 a.m. is also booked to pass Swindon in the opposite direction, with 73 minutes left in which to complete the 77¼ miles to town. That is to say, the combined time of the two trains for a distance of 154½ miles, from Paddington to Swindon and back, is 150 minutes. This is travelling with a vengeance!

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the pioneer engineer of the Great Western Railway.

The gradient has now turned in favour of the engine, and the speed begins to rise. Sweeping through Wootton Bassett, where the Badminton line leaves us on the right, we reach the crest of the short 1 in 100 descent to Dauntsey at round about 70 miles an hour. A tremendous acceleration should carry us well into the “80’s” by the time we pass the latter station, especially if we are running at all late. On one recent trip by this train we were doing 85 miles an hour at Dauntsey, and averaged 75.6 miles an hour over the 16¾ miles from Swindon to Chippenham. From Dauntsey to Corsham the grades are slightly against the engine, and the speed falls gradually until we enter the deep cutting beyond Corsham Station at about 60 miles an hour. The blackness of the Box Tunnel lies immediately ahead.

In early railway days the Box Tunnel was looked upon as an engineering work of great note, and with its 11 miles of length was considerably the longest railway tunnel of its time. Nowadays there are many other tunnels, chiefly abroad, but some also in this country which outdo the Box Tunnel both in length and also in the overcoming of difficulties to which their present existence bears witness. But scientific knowledge was much more limited when the Box Tunnel was bored, and those who were responsible therefore deserve the more credit for their achievement. As compared with later British tunnels, it is of very large dimensions, which are apparent as you enter it; anti a more striking feature, which you will not be able to see, is that for half a mile of its length the line passes through an enormous natural cavern in the freestone, 40 ft in height and 30 ft in width, in the shape of a Gothic arch. The Box Tunnel is very noisy, the rails laid in it suffering from that curious phenomenon known as “roaring”, generally due to the effect of damp in pitting their running surfaces into minute crests and hollows.

Through the tunnel we are on the second 1 in 100 down-grade, and the speed again rises high, probably well into the “70’s”, and possibly again above 80 miles an hour, though not often to the latter figure here. We now see the city of Bath ahead, lying in the natural amphitheatre of hills that adds so much to its beauty, and we notice the ornamental stonework that decorates the railway as it is carried through the gardens on the London side of the town. Speed here is drastically reduced, for the line passes through Bath on a sharp curve. Just before reaching the station the guard of the “Bath Spa” portion looses off his two coaches, and looking back we see them stop in the centre of the platform on the stroke of one o’clock, or even a shade earlier.

The remaining half-dozen coaches of our train are a plaything for a “King”, and 15 minutes is a generous allowance for the last 11½ miles of level track into Bristol. We shall just touch 60 miles an hour or so at Keynsham - we may even get to 70 if the train is late - where the track-troughs at Fox’s Wood allow for another re-filling of the tender. There are one or two short tunnels along here, distinguished by the bold architecture of their entrance. At ten minutes past one we should be passing St. Anne’s Park, and after passing round sinuous curves through some not very attractive manufacturing outskirts of Bristol, we run slowly into Temple Meads Station at about 1.12 or 1.13 p.m, having maintained an average of exactly 60 miles an hour all the way from Paddington. That is, of course, if we have had no bad delays, and especially outside Temple Meads Station itself, whose traffic has now long outgrown its limited accommodation, so that signal checks in the last mile - notably on summer Saturdays - can be very severe.

We have now four hours in which to amuse ourselves in Bristol. Of the two up two-hour expresses, one left an hour-and-a-half ago, at 11,45 a.m; but this is the lighter of the two trains, so that it is much preferable that we should wait for the 5.15 p.m. up. Like the train by which we have just come down, the 5.15 carries two slip portions, one for Swindon and the other for Reading, and its timing is made more difficult because it is booked to take the platform road at Reading to detach the latter slip portion, which means a bad slowing and the loss of quite two, if not three minutes in the running. Indeed, the 5.15 p.m. up is without much question the hardest of the four two-hour Bristol expresses, and as it never is allowed any more powerful locomotive than a four-cylinder 4-6-0 “Star”, its punctuality record is not so good as that of the other three trains. For some years past, indeed, it has been very seldom that I have recorded an arrival dead on time at Paddington with this train.

We ought to recognise the main portion of the train as it draws into Temple Meads from Weston-super-Mare at 5.2 p.m. - in charge, probably, of a 4-4-2 express tank engine - for it is the “set” in which we travelled down by the 11.15 a.m. from London. At the back of this has been attached a composite coach, and behind that, again, a composite slip brake and a bogie third for Swindon, and another composite slip brake, with probably another third, for Reading. The slip portions are both very popular, and the Swindon one, in particular, makes an important connection there with the through express from Penzance to Aberdeen, which leaves Swindon at 6.20 p.m. Once again, therefore, we have a train of 11 vehicles, whose full weight is very little short of 400 tons, and first-class locomotive work will be necessary if we are to keep time. Not only is the schedule, for the reason already given, the hardest of the four, but the grading, as we shall see in a moment, is considerably harder on the up journey than on the down.

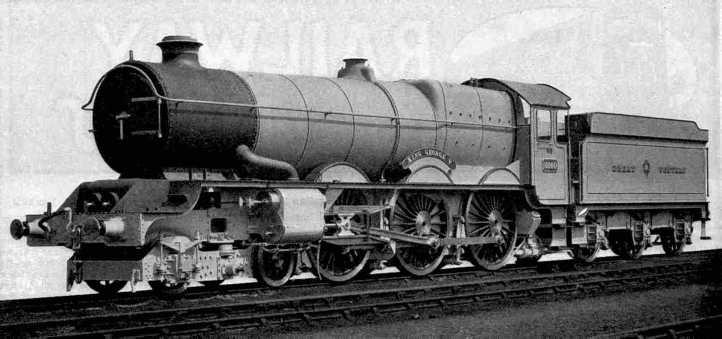

“King George V” the magnificent 4-cylinder 4-6-0 G.W.R. Passenger Locomotive that created such enthusiasm in America on its visit to the Centenary Celebrations of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

Immediately we leave Temple Meads we diverge to the left from the route by which we entered that station, as though we were travelling to South Wales. This carries us through Stapleton Road - an important Bristol suburban junction - where, before we have attained more than 40 miles an hour, the engine is faced with two miles of climbing past Ashley Hill at the formidable figure of 1 in 75! A nice obstacle in the middle of a run whose average speed is to be all but 59 miles per hour! It will not be at much above 20 miles an hour that we clear the summit of this bank; but in fact, if we were travelling much faster, it would be necessary to slow immediately afterward through Filton Junction, where we diverge to the right from the Bristol to South Wales line. Bearing round to the right, we then join at Stoke Gifford the main line from Paddington to South Wales, over which we travelled by the “Fishguard Boat Express” a good many months ago. We are here within 6½ miles of the mouth of the Severn Tunnel, but it does not, of course, lie on our route.

From Stoke Gifford the engine still has rising grades ahead for some 11 miles, the inclination of the ascent being uniformly 1 in 300. We shall forge ahead up this bank, possibly attaining 50 miles an hour, or a trifle over, but more probably maintaining an even rate of about 47 or 48 m.p.h. At Chipping Sodbury we pass over water-troughs, followed at once by the 2½ miles’ length of Sodbury Tunnel, under the western spurs of the Cotswold Hills. This brings us to Badminton, the summit of the climb, where we are precisely 100 miles from London. With our heavy train we shall almost certainly have taken 26 to 28 minutes to reach this point, so that we have only from 94 to 92 minutes left in which to complete our last century of miles. But fortunately we have nothing but faintly falling grades or dead level ahead of us.

Through Hullavington and Somerford the line falls at 1 in 300, and provided that the driver has not to refill his boiler after the hard climbing, in which case easier running would be necessary, we shall touch or exceed 75 miles an hour, and may even get to 80 an hour. Then we have to reduce speed slightly over the junction at Wootton Bassett, so that the 40¼ miles to Swindon may be expected to have taken us at least 48 minutes. Here the Swindon “slip” is detached, on the centre road, an engine being ready to draw it to the platform directly we have passed. Seventy-two minutes left for 77¼ miles! Can we do it? With the right driver, yes, most certainly!

Along the faint descent from Shrivenham onward the speed creeps up - Shrivenham, 70; Uffington, 72; Wantage Road, 75; Steventon, 76 or 77, and possibly but only occasionally 80. So we sweep through Didcot and past the Thames Valley stations - Cholsey, Goring, Pangbourne, Tilehurst. Swindon to Didcot, 24¼ miles, 20 minutes; Didcot to Tilehurst, 14¼ miles, 11¾ minutes; this is “going some”! Steam is shut off; we brake down to 30 miles an hour, and roll slowly through the platform road at Reading to drop our second “slip”. We have covered the 41¼ miles from Swindon in 35 minutes, and now have 37 minutes for the 36 miles to Paddington - an easy task.

By Twyford we are doing over 65 miles an hour, and from Maidenhead through Slough to West Drayton or Hayes are probably well up in the “70’s” again. At Southall we begin to ease, and somewhere about Old Oak Common steam is shut off; so we drift on past Westbourne Park, and, if we are lucky, get through Royal Oak without a signal check. The big arched spans of Paddington roof are in sight ahead, and we roll gently round the curve and stop dead at 7.14 by the clock, a minute early! We have covered the 77¼ miles from Swindon in 71 minutes, and the 100 miles from Badminton in 91½ minutes. This does not happen every day, but we have been fortunate in having one of the best of the Bristol drivers on the footplate. Go and congratulate him; he has given you some of the fastest long distance railway running in the world.

Just at the time of completing this article, I have received details of some most remarkable runs that have been made in recent months on this 5.15 p.m. up two-hour express, and the Editor tells me that there is just room in which to mention them. The most astonishing was probably a trip on which the two-cylinder 4-6-0 engine “Saint Bartholomew” had not only a severe signal delay outside Bristol, but also had to make a special stop at Badminton in order to pick up a distinguished traveller. After doing this, the driver actually succeeded in covering the 100 miles to Paddington, with a slight signal check at Westbourne Park, in 86 minutes, 40 seconds! The 90 miles from Hullavington to Acton were reeled off in 73 minutes, 53 seconds, at an average speed of no less than 73 miles an hour for the whole distance; and this included both the usual slowing over Wootton Bassett Junction and the worse one for slipping the rear coach in Reading platform. A top speed of 80 miles an hour was reached both near Didcot and again on practically dead level track at Slough.

On a second occasion “St. Andrew” had to make the same stop at Badminton, and in addition to this, owing to permanent way operations in progress at Reading, was made to stop there to detach the Reading “slip”. Yet, after two dead stops in what should have been a non-stop run, and bad signal checks between Acton and Paddington, the 117.6 miles from Bristol to Paddington were completed in only 22 seconds over the two hours! The 64 miles from Badminton to Reading were covered in just under 57 minutes, start-to-stop, and the 36 miles from there to Paddington, allowing two minutes for the final delays, in 35½ minutes.

I was fortunate, myself, too, in being on the train when one of the 4-cylinder 4-6-0 engines “Italian” had the really tremendous load, for this hard train, of 12 big 8-wheelers, weighing all but 400 tons in all out of Bristol. Yet we should have run into Paddington three minutes early but for checks from Old Oak onward, and in this case the 90 miles from Bullavington to Acton took exactly 78 minutes, with an average speed of 69 miles an hour!

Bristol Two-hour Express, hauled by “Castle” class locomotive, passing Swindon Works at full speed.

You can read more about “The Birkenhead Diner”, “The Fishguard Boat Express”, and “The Torbay Limited” on this website.