A Famous Train of the GWR

FAMOUS TRAINS - 21

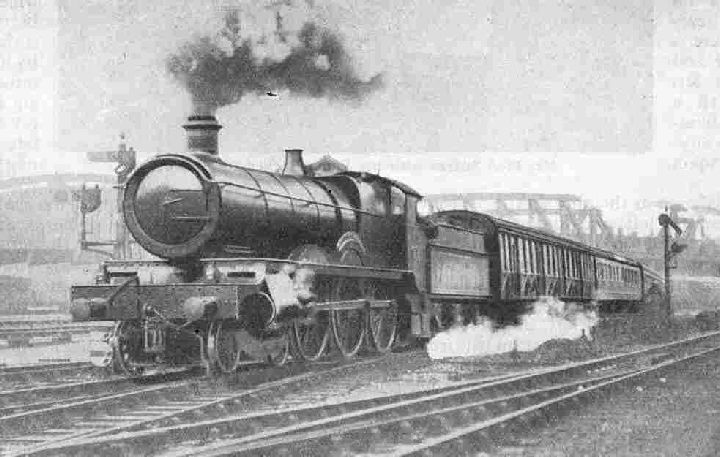

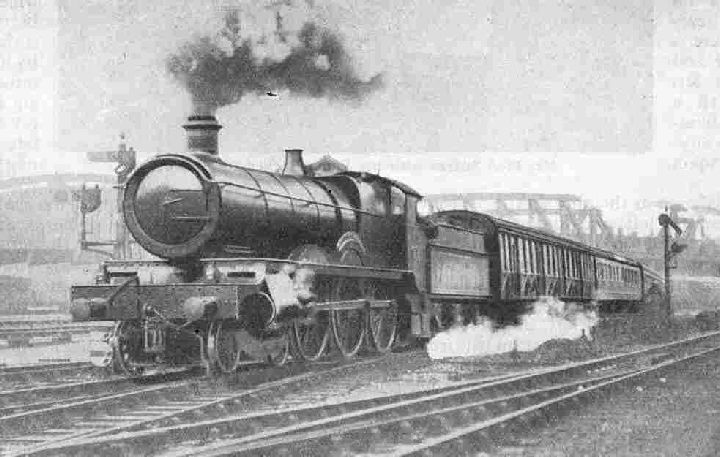

The Paddington-Fishguard Express leaving Paddington, Engine No. 2933 “Bibury Court”.

ONCE again the subject of our consideration is to be a “boat” express - that is, a train run in direct connection with a steamer service. North-eastward and south-eastward we have hurried from London, in previous articles, in order to cross to the Continent of Europe; this month we are going due westward, en route to Ireland.

In one sense Fishguard is unlucky. For a time it figured as a transcontinental port, when the Cunard liners from America were calling there to set down passengers and mails for London and the Continent, on their way to Liverpool. While this arrangement was in force, the Great Western Company made some wonderful running between Fishguard and Paddington, doing the 145¼ miles from Cardiff to town at an average speed of over 60 miles an hour on several occasions. Some of the fastest overall times in history between New York and London were made during the period in question.

But the Cunard Company succumbed later on to the superior charms of Southampton, instead of Liverpool - as most of the big trans-Atlantic lines have done, the Southampton route making possible also a direct Continental call at Cherbourg - and this added glory of Fishguard therefore ceased to be. The Great Western have lately derived a good deal of compensation, however, from the calling of various Atlantic liners regularly at Plymouth, on the inward journey, whence passengers and mails are whirled to Paddington by Great Western “fliers” in but little over four hours.

When the port of Fishguard, which is a Great Western Railway creation, was completed, day and night steamer services were instituted between there and Rosslare, a new port on the Wexford coast of Ireland, with special connecting trains from there to Waterford and Cork. From Paddington the boat expresses left at 8.45 in the morning and 8.45 in the evening. During the war, however, the day service vanished, although the connecting express, with its important South Wales stops and connections, still runs at the slightly altered departure time of 8.55 a.m.

The night service was first altered to 8 p.m. out of London, and then, in harmony with the systematic departure times of expresses that were standardised a couple of years ago - whereby you now leave Paddington for Birmingham and the North at 10 minutes past the hour, for Bristol at 15 minutes past, for the West, of England at 30 minutes past, for the Oxford and Worcester line at 15 minutes to, and for South Wales at five minutes to - it became 7.55 p.m, which is the present starting time. The train has a total distance of 261¼ miles to cover, which has, on the occasions of special “day excursions” to places as far afield as Killarney, been done on several occasions without intermediate stop. To-night we shall stop at Reading, next at Newport and the closely adjacent city of Cardiff, and last at Swansea. The longest of these stretches is the 97½ miles from Reading to Newport, so that the train does not actually cover any distance in excess of 100 miles without intermediate stop.

Before we start, we must take a look at the train, which we shall find at No. 2 platform at Paddington. It varies a great deal in its composition, according to the season of the year, so that it is difficult to give precise details. At the rear end we find two or three coaches for Bristol, and we may well wonder how they are going to get there, seeing that we do not stop between Reading and Newport, until we notice on the back of the outermost coach the familiar red-and-white tail signals which indicate that this is a “slip” portion. They are to be dropped off at the back of our train away in the open country at Stoke Gifford East Box, some 6½ miles away from Bristol, and there a tank engine will take them in charge, and run them down into Temple Meads, what time we are diving downward in the opposite direction into the recesses of the Severn Tunnel.

Next come a couple of the vast Great Western 75 ft “Ocean Mails” vans, destined to be next the engine when the express leaves Swansea. A sleeping car is the next vehicle, and if we fail to recognise its external lines as being truly “Great Western”, it is possible that this is one of the cars acquired some time ago by the GWR from the late London and South Western Railway, after the unsuccessful experience of the latter company in running sleeping cars between Waterloo and Plymouth. In front of this comes the ordinary passenger portion of the train, which may consist of five or six 70-ft corridor coaches, or more, and then next the engine, the all-important “diner”, which is to be left behind at Swansea.

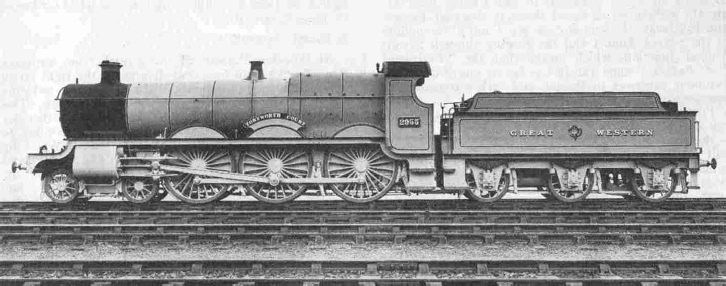

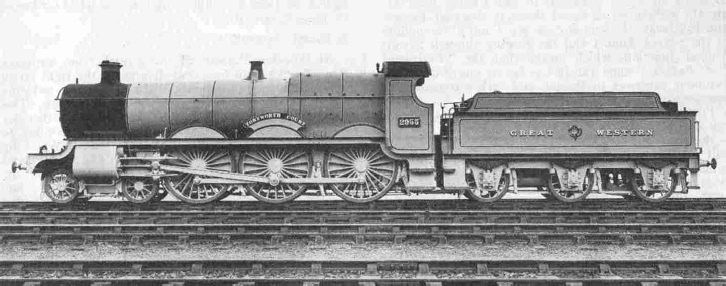

Usually, therefore, the complete train is very heavy, and on this account it is the more surprising that its haulage, until quite recently, has been customarily entrusted to one of the two-cylinder “Saint” class 4-6-0 engines. These engines have always been at home on such moderately-weighted trains as, say, the up Bristol two-hour expresses, and Great Western drivers look on them as the freest-running and fastest engines on the system; but a train of 400 tons, and up, at times, to 450 or even 480 tons or so, is a tough proposition indeed for engines of this class. But, given a clear road, we shall find that our engine can just about manage it.

It was with No. 100 (now No. 2900) “William Dean”, the first engine of this type, built in 1902, that Mr. Churchward set some striking new fashions in British locomotive design. Never before had so long a piston-stroke as 30 inches been tried in this country. It was done in order to make full use of the expansive properties of the steam, and to encourage the full-open regulator and short cut-off driving practice that has since become general on the Great Western Railway. In those days, too, 200 lb per sq in was a high working pressure, and when, in following the purchase of three French-built compound “Atlantics”, the figure was further advanced to 225 lb - where it has since remained in the chief Great Western express locomotive designs - Mr. Churchward laid the foundation of some of the finest locomotive constructional practice that this country has vet seen. Now even the figure of 225 lb per sq in working pressure is eclipsed by that of the new “Cathedral” class 4-6-0 engines, which is fixed at 250 lb per sq in.

When at last we get away from Paddington, we find the first stretch of the journey constitutes what is perhaps the easiest of all its schedules, though certainly not the slowest. We have to cover the 36 miles out to Reading in what is now the standard start-to-stop time of 40 minutes, at an average speed of 54 miles an hour. At Southall, or shortly afterward, we reach and cross the “sixty” line; by Slough we may be doing 65 an hour and upward; so that, apart from checks, the negotiation of Brunel’s stretch of straight and perfectly level track will not involve our engine in any difficulties, load notwithstanding. There is much to be done at Reading, to which point important connecting trains bring luggage and mails for South Wales and Ireland. Hungry passengers for Bristol who have snatched a hasty meal in the dining-car on the way from Paddington hurry back to the “slip” and quite possibly the time-table allowance of 5 min. may not prove quite sufficient.

The Fishguard Express is generally hauled either by an engine of the “Court” class or one of the “Saint” class. The illustration shows Engine No. 2955 “Tortworth Court”.

The next section, from Reading to Newport in Monmouthshire, is probably the hardest stage, of the journey. The distance is 97½ miles - the nearest to 100 miles of all our point-to-point runs - and the time allowed is 103 minutes, entailing an average speed of all but 57 miles an hour. Included in this timing, however, are the reductions of speed through Wootton Bassett and Patchway, the long and steep pull out of the middle of the Severn Tunnel and the slowing through Severn Tunnel Junction, which means that the “Fishguard Boat Express” must run just as fast as one of the down two-hour expresses to Bristol, and with a considerably heavier load.

From the standpoint of the driver and fireman, too, a run of this kind is the more difficult in that for some 65 miles from the Reading start the locomotive has not a moment’s “breathing space”. There is no downhill worth the mention, and the gradients, though ever so slightly yet none the less continuously “against” the engine, require almost unbroken effort in order to maintain time.

For 47 miles from Reading, Brunel’s old main line to the West of England is still followed. On the first level stretch of 17 miles to Didcot, the first set of water-troughs is passed at Goring, and our thirsty steed picks tip a good supply. At Didcot, 53 miles out of London, the old Birmingham route diverges on the right, making first for Oxford; now, of course, trains to the North take the much more direct route through High Wycombe. Didcot, too, sees the end of the four-track section from Paddington; the tracks now converge to two. For 17 miles from here the line is definitely uphill - faintly, it is true, but a continuous grade of even 1 in 660 to 880 is felt by the engine when loaded as heavily as this, and our speed may drop back from 65 an hour or so to about 60 an hour or a shade less, on to Swindon. If it is still light enough and we look out on the north side of the train, just beyond Didcot, we shall notice the big Government depot that extends for several miles alongside the track, and specially careful observation may reveal one of the Great Western 0-6-0 tank engines that has been specially fitted with a chimney of vast size, in order to catch all sparks that may be emitted when the engine is working near sheds that contain inflammable material.

So we hurry on through Shrivenham, and then through Swindon, with its miles of sidings and its great locomotive, carriage and wagon shops. It is interesting to recollect, as we pass Swindon Station at full speed, that the Great Western Railway only succeeded in obtaining release from their obligation to stop all trains at Swindon for 10 minutes by paying over to the Swindon Hotel and Refreshment Room Company a sum of money in five figures, in 1895, as compensation to the latter for loss of business so caused.

At Wootton Bassett, 5¾ miles further on, we leave Brunel’s old main line, and diverge to the right on to what is known as the South Wales Direct line, reducing speed for the purpose to about 50 miles an hour. This “cut-off” was opened in 1901, curtailing the distance from London to South Wales by 11½ miles and cutting out the congested line and awkward curves through Bath and Bristol. With this route and the previous Severn Tunnel line from Bristol under the Severn, to which we shall come presently, the route from London to South Wales is now shorter by 25 miles than it was in the old days, when trains travelled right round from Swindon by Gloucester and the down right bank of the Severn.

At first the line falls from Wootton Bassett, but then follows a trying ascent which, from Little Somerford nearly to Badminton, is unbrokenly for nine miles at 1 in 300. Here again it is, of course, the weight of the train that constitutes the real difficulty, although with a two-cylinder “Saint” and no less than 485 tons I have timed a minimum speed of 55 miles an hour at Badminton - a marvellous feat indeed. Quite probably we shall drop to about 50 an hour at the summit of the ascent. Badminton is 64 miles from Reading and exactly 100 miles from Paddington; from Reading the time-table allows us 66 minutes. An interesting point about the Badminton line, by the way, is that the sleepers throughout are not of the usual creosoted pine variety, but are cut from the Karri and Jarrah hardwoods of Australia, which are very long-lived and need no preservative treatment.

At Badminton we are at the highest altitude of the journey between Paddington and Newport, and 20 miles of downhill now lie ahead. Immediately after Badminton we plunge into a long tunnel, and the uninitiated traveller, blissfully unconscious of the fact that we have been climbing for some time, immediately jumps to the conclusion that he is passing under the River Severn. But this is not just yet, though Sodbury Tunnel, under the Cotswold Hills, is quite a respectable bore, being just over 2½ miles in length. Directly we are through, the driver sees ahead of him the troughs at Chipping Sodbury, and once again the engine is glad of the opportunity of replenishing the greatly depleted tender tank.

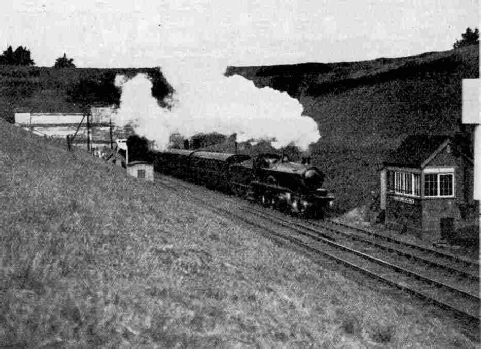

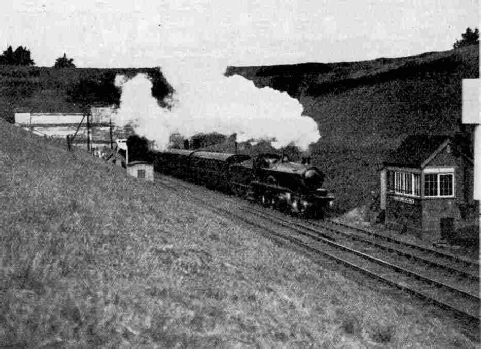

A swift run down 11 miles of 1 in 300, from Badminton Station, brings us to the sidings at Stoke Gifford, where the Bristol slip portion drops quietly off the rear, as we pass the East Box. For the curve from the West Box round to the old South Wales main line from Bristol which we join at Patchway, speed is reduced to 45 miles an hour or so. Immediately after Patchway we see the up line beginning to fall below us, finally passing into a tunnel; shortly after this we also pass into a tunnel, and emerge to find the up line now well above our heads. The reason is that the old Severn Tunnel on which the down trains now travel, is inclined steeply downward, first for a mile mostly at 1 in 80, and then for another at 1 in 68, followed by a mile of level. To ease this intolerable gradient for up trains, half-a-mile was taken from the short “levels” on both sides, and for roughly three miles a separate location was found for the up line, with a smooth gradient of 1 in 100 throughout.

At Pilning Station there begins the real descent into the famous tunnel itself. This continues for 3½ miles to the very centre of the Severn, at an inclination of 1 in 100, after which comes the pull out of the north end, for three miles at 1 in 90. Drivers are not allowed to rush the descent at full speed in order to lift their trains quickly out of the other end, and although we may have noted a startlingly rapid acceleration down the first incline from Patchway, we shall not find any speed much in excess of 60 miles an hour being made through the Severn Tunnel.

Severn Tunnel, English side.

The story of the tunnel, and the dogged perseverance of those who carried through its construction may be found in the article “The Severn Tunnel”. Time and again water broke into the workings, both from the ends and in the middle. The curious natural phenomenon known as the “Bore”, which at certain times sweeps up the Severn like a kind of tidal wave, was responsible for the former irruption, and most of the latter trouble was caused, not by the Severn itself breaking through, but by a vast underground source of water which became known afterwards as the “Great Spring”. Even since the completion of the tunnel it has become necessary to lay down permanent pumping plant capable of evacuating from the tunnel some twenty million gallons of water every day, as well as an elaborate plant for supplying fresh air to the tunnel, in consequence of the impossibility of boring the usual ventilating shafts. Altogether the Severn Tunnel used up 77,000,000 bricks and 37,000 tons of cement, took 11 years from its first beginnings to its completion - largely in view of the water difficulties - found occupation for 3,628 men in all - and cost some two million sterling.

At the top of the ascent out of the tunnel our speed will probably be under rather than over 30 miles an hour, but after negotiating the crossings at Severn Tunnel Junction, where we join the oldest of the South Wales routes - the original one through Gloucester, which has come along the Severn past Chepstow, and has passed over our heads just before we left the tunnel and a brief level run of just under 10 miles brings us into Newport, 133½ miles from Paddington, at 10.23 p.m. The third set of track-troughs is passed over just beyond Severn Tunnel Junction.

We are now well into the industrial areas of South Wales, and between Newport and Swansea, were it not the dead of night we should see many evidences of mining and manufacturing activity. Railway after railway, coming down from the mountain valleys on the southern slopes of the Brecon Beacons and their outlying hills, comes down either to join us or to cross our path. Before the war these were all separate concerns, but they have now been merged into the Great Western, and so the Taff Vale, the Rhymney, the Barry, the Cardiff, the Brecon and Merthyr, and many other railways have lost their separate existence. After a stop of six minutes at Newport, there follows the brief run of 11¾ miles to Cardiff, compassed in 16 minutes, and for a large part of the distance through the middle of mile after mile of sidings, filled with coal trucks or “empties”.

Cardiff, reached at 10.45 p.m, was at one time always an engine-changing centre, but now quite possibly our engine will run through to Swansea. When we leave Cardiff at 10.49 p.m, the engine is faced with some more difficult grades ahead. From Ely, just beyond Cardiff, the line rises for 11 miles to Llanharan, with a final 1½ miles at 1 in 106, and then drops sharply for 3½ miles at 1 in 126-157 nearly to Bridgend. From there we go up for three miles at 1 in 132-163, and then down again at 1 in 93-139 for 3½ miles past Pyle. The engine has now some short respite on to Neath, but there is a severe slack over the curves through Neath, where some of the high ground of South Wales comes down nearly to the sea, followed by a stiff climb of 2¼ miles at 1 in 90 to Llansamlet, and an equally steep drop from there into Landore. On the way up to Llansamlet, at Skewen, we pass the vast oil refineries that have been established of quite recent years.

We could miss Neath and Swansea altogether by following from Court Sart junction the “South Wales Avoiding Lines” - a new main line, opened some years ago, largely no doubt, in view of the probable development of Fishguard as a trans-Atlantic port - and though this would cut out some difficult grades, as well as saving distance, Swansea is too important a place to miss. At 11.47 p.m. we reach the centre of the “tin-plate” industry, having covered the difficult 45¾ miles from Cardiff in 58 minutes. Until quite recently the Swansea connection was made at Landore Junction, 1¼ miles away, which avoided the reversal of the train at Swansea, but the latter procedure has now become standard with all the expresses proceeding to West Wales. So here we leave behind the engine that has brought us from Paddington, and the dining car as well, and with - probably - another two-cylinder 4-6-0 on our reduced train of about eight vehicles, we head westward again at 11.51 p.m. for Fishguard.

The remaining run of the journey is 73 miles in length, bringing the total mileage of the train up to 264 miles. This last stretch has a number of obstacles, the first of which is the very severe Cockett bank of 1½ miles at 1 in 52; up this quite possibly we may receive the assistance of a “pilot” or a “banker”. But after the descent to Gowerton we have a long stretch of some 35 miles of almost dead level track, past Llanelly, Carmarthen and St. Clear’s, followed by short but increasingly sharp undulations to Clarbeston Road, where we leave the original Milford line. Some nine miles of these ups-and-downs are round about 1 in 100 in steepness, Clynderwen and Clarbeston being both “summit” points. The “cut-off” from Clarbeston to Letterston, which preceded the opening of Fishguard Harbour, has also a sharp three-mile descent and 2½-mile ascent in the middle of it, at the same inclination. And then, last of all, there comes the tremendous three-mile descent from Manorowen into Fishguard, two miles of which are at 1 in 50, up which all the London-bound trains of any weight have to be banked.

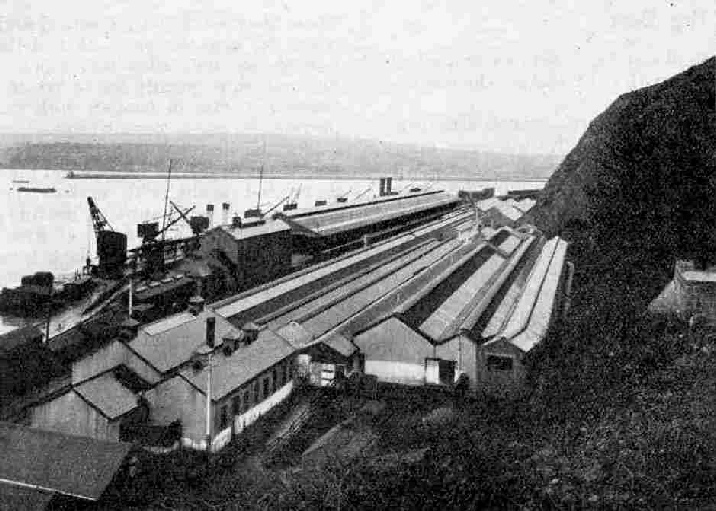

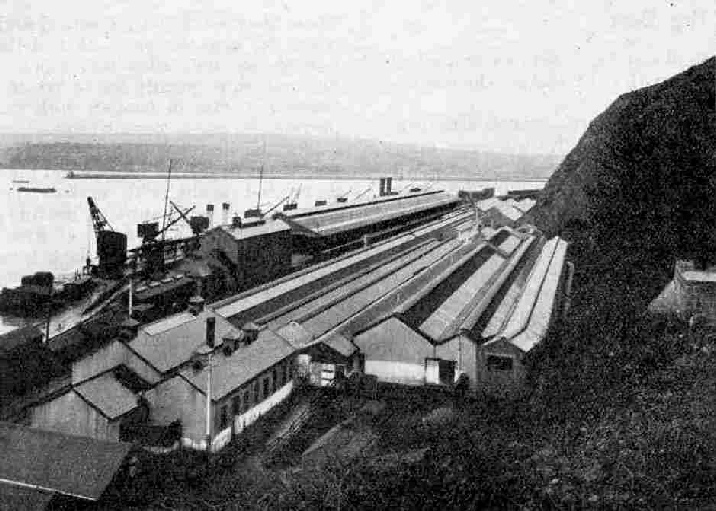

Fishguard is another wonderful Great Western achievement of which much might he written. No expense was spared in equipping the port, again doubtless with a view to trans-Atlantic traffic which, alas! has not come to full fruition. Two million tons of rock were blasted out of the hillside and dumped into the sea, making available a level area of 27 acres on which to make the station and the quay, and also going towards the construction of the great northern breakwater, which stretches 2,000 ft out to sea and has created a magnificent harbour. Before the coming of the railway Fishguard was a remote little village, completely shut off from England by several counties of Wales.

To-morrow morning, when you wake up, will be the time to see all these things; now, at 1.25 in the morning, it is high time to get to bed. But let me tell you that before you wake the “Fishguard Boat Express” on which you have travelled so comfortably from Paddington will be well on its way back Londonward with its passengers from Ireland. Less than two hours after its arrival, at 3.15 a.m, its hard-worked rolling stock is again on the move, to complete its daily round of some 535 miles.

The Station and Quay, Fishguard.

You can read more on “The Cheltenham Flyer”, “The Cornish Riviera Express” and “The Severn Tunnel” on this website.