A Famous Train of the GWR

FAMOUS TRAINS - 32

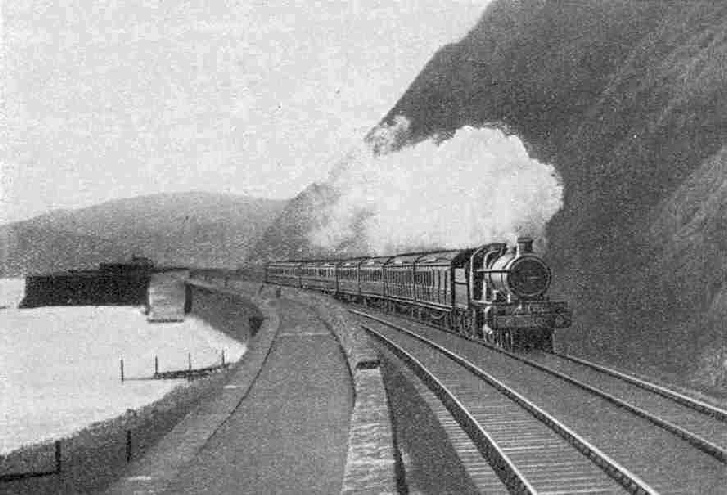

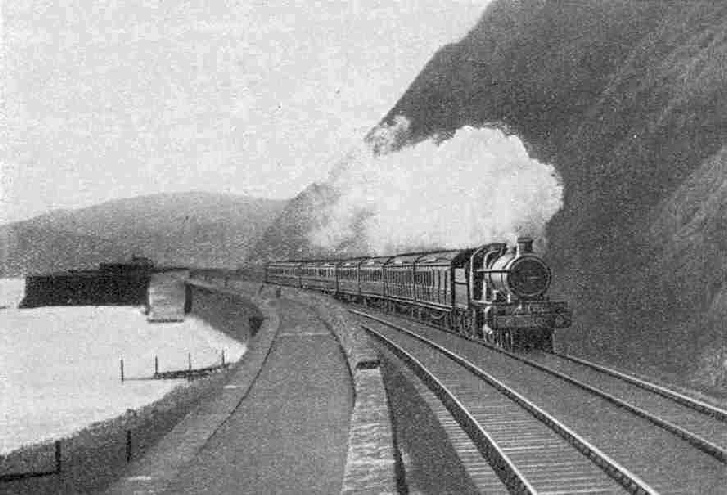

The “Torbay Limited” passing the sea-wall at Teignmouth.

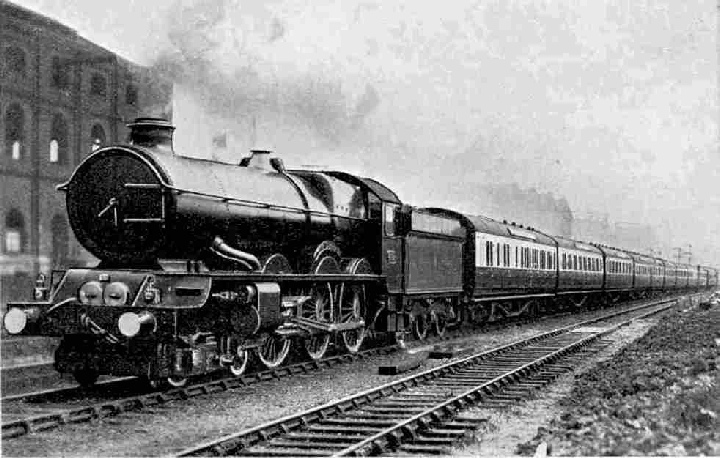

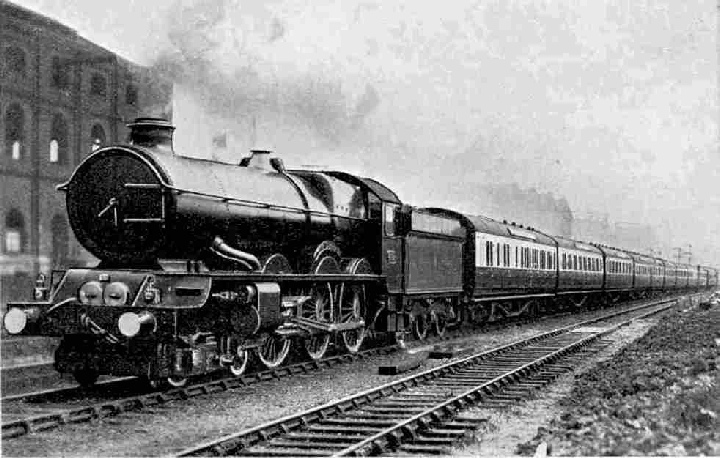

IT is a year and a half since we took our last trip over the West of England main line of the Great Western Railway, so that most of you probably will have quite forgotten what it looks like. Another reason why we should travel over this line again is that since that journey on the “Cornish Riviera Express”, there have come into use over this route some of the most remarkable locomotives in the country. It was in July of last year that the first of the “Kings” took the road from Swindon Works, completely dwarfing the previous GWR 4-6-0 engines, not excepting the “Castles”. And not only so, but the “King George V”, with a tractive effort of no less than 40,300 pounds, both held and still holds a substantial lead in tractive power over any other express locomotive type in this country, the nearest approach being the super-“Pacifics” of the “Enterprise” type on the LNER.

What is the secret of this enormous tractive power? It lies chiefly in the use of a working steam pressure as high as 250 lb per sq in - 25 lb higher than that employed on any other express locomotive type on the GWR, and far above the figure of 180 to 200 lb so common on other lines. Since then the “Royal Scot” engines of the LMS have been turned out with the same pressure, but owing to a considerably smaller volume of cylinders their tractive effort figure falls a long way below that of the “Kings”. Ample cylinder power is always a feature of Great Western designs, and to this rule the “Kings” are no exception; dimensions of 16¼-in diameter by 28-i stroke, which apply to all four cylinders, witness to the long and narrow bore so well adapted to the Great Western practice of early cutting-off and ample expansion.

Another notable feature of the “Kings” is the way in which the adhesion weight - that is, the proportion of the weight of the engine coming down on the driving wheels - has been advanced above what was previously regarded as the safe maximum of 20 tons per axle. This maximum was fixed, of course, to keep within reasonable limits the weights coming down on the track and underline bridges. But recent experiments have proved that the worst harm to track and bridges is done by powerful two-cylinder engines. For certain technical reasons it is impossible fully to balance the forces set up by the heavy reciprocating and rotating parts of such engines when they are running at speed, with the result that with each revolution of the driving-wheels there comes a heavy impact, or “hammer-blow” on the track, which adds considerably to the effective

weight coming down upon that pair of wheels. With a three-cylinder engine, however, and still more with a four-cylinder engine, conditions are vastly improved; in fact the four-cylinder engine virtually balances itself owing to the four cranks splitting up the circle into four equal parts of 90 degrees each. Thus it is that in all the latest British three-and four-cylinder express passenger designs axle-loads have been increased beyond the 20-ton figure. “King George V” heads the list with 67½ tons on the three coupled axles. Previously, or in existing conditions on the Continent of Europe, where the tracks are generally of strength inferior to our own, such a loading would have required eight-coupled driving wheels.

It is within the knowledge of most of you that “King George V” has already made a trip across the Atlantic to the United States and back, for exhibition at the “Fair of the Iron Horse” with which the centenary of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was celebrated last year. After going in solemn procession round the demonstration track in the fair-grounds at Baltimore, with many of the latest and most powerful American locomotive types - some of them up to twice the weight and size of our British representative, owing to the more generous limits of the American rolling stock construction gauge - “King George V” tried some running over American railroads, going from Baltimore to Washington and back in charge of the famous Old Oak driver William Young.

American rolling stock proved a tough proposition for a British locomotive, the twelve-wheeled all-steel care weighing anything from 60 to 80 tons apiece, as against the 35 to 37 tons of the latest Great Western 70-ft coaches. The British “King” did quite well with a train of nearly 700 tons, however, despite difficulty experienced in burning in the small British firebox the poor quality coal used on American locomotives. A maximum speed of 75 miles per hour was attained, and we are told, indeed, that Driver Young was peremptorily instructed to reduce this speed to a mile-a-minute and no more. Much capital was made out of this story at the time, as though our American cousins do not know what speed is, but this, of course, is far from the truth. The fact is that American railways are generally unfenced, that there are “grade crossings” innumerable - of railways over roads and over other railways as well - that not unfrequently they run up the main streets of towns, and that for these and many other reasons the main lines are infested with compulsory “reduce speed” orders, some of which, doubtless, were being approached at the time referred to. On other American routes, which I have not space to name, very tight bookings are in force, and speeds are attained little if at all inferior to those to which we are accustomed in this country.

Down “Torbay Limited” express leaving Paddington. Four-cylinder 4-6-0 locomotive No. 6012 “King Edward VI”.

But I am wandering far, I fear, from the “Torbay Limited”. Why “Limited?” “Limited” is a description of American origin, indicating passenger accommodation limited to a certain maximum number of places that can be booked in advance. Where strictly adhered to, this may mean that places on a popular “limited” express may have to be booked days in advance, or you may never get on to it on the day of your desire. In our own country the only true parallel is probably found in the “Pullman Limited” trains, such as the “Queen of Scots”, on which we travelled previously. It is only in the neighbourhood of Bank Holidays or at the busiest summer week-ends that the “'Torbay Limited” becomes a real “limited express”, as occasions have not been unknown when the first portion of the “Torbay”, made up to its maximum single-engine load, has gone out of Paddington with “booked seat” passengers only. But another subsequent train is always run for those who have not been so farseeing.

Torquay has much for which to thank the Great Western Railway authorities. All the year round the “Torbay Limited” brings the famous watering-place within 3 hours 35 minutes of Paddington, although the distance so bridged is 199¾ miles. When non-stop running is resumed over summer, the time will be cut to an even 3½ hours - the quickest ever yet scheduled between Torquay and London - involving an average speed throughout of 57 miles an hour. Exeter, 173¾ miles from Paddington, now reached in 175 minutes, will be passed in 174½ minutes, as in the case of the “Cornish Riviera Express”, and both trains are already timed to maintain an average rate of 60.4 miles per hour continuously over the 164¾ miles between Southall and this Cathedral City of the west. This I believe to be the fastest schedule in the world continued unbrokenly over so great a distance. It is not only Torquay that benefits by this lightning running, but also Paignton and Brixham, fringing Torbay, as well as Kingswear and Dartmouth, in the neighbouring Dart Valley.

A through portion to and from Plymouth is also run on both up and down “Torbay Limiteds”, detached on the down journey at Exeter and attached on the up journey at Newton Abbot. Coming to London the up “Torbay” - with the further addition at Brent of a through coach from Kingsbridge, which went down the previous day on the “Cornish Riviera Express” - makes a non-stop run of 194 miles from Newton Abbot to Paddington, missing Exeter. Owing to the longer time spent at Newton

in marshalling the train, the up “Torbay Limited” requires 3¾ hours from Torquay to London, or 10 minutes more than the down train; but the allowance of 205 minutes from Newton to Paddington entails an average speed all the way of all but 57 m.p.h. Doubtless in the altered times that will operate from early in the present month, during the summer season, the up “Torbay Limited” will make the nonstop journey from Torquay to London in the same time of 3½ hours as the down train.

As we made our last West of England journey in the down direction, we shall get a new perspective of things on this occasion if we try the up “Torbay Limited” and this means that we must betake ourselves to Dartmouth. Dartmouth is, from the railway point of view, singular in having a railway station but no trains. Between this station and the actual starting-point of the “Torbay” there stretch the waters of the Dart. So, though you take your railway ticket in quite an ordinary kind of booking-office at Dartmouth, a steamer journey across the river awaits you ere you find your train at Kingswear. Certain bridges between Paignton and Kingswear having been rebuilt recently, the heaviest engines are now permitted to work right through to Kingswear, and in the height of the summer it is quite possible that we may find our “King” heading the train from the start, in place of the humble 2-6-2 tanks which always previously performed the duty of haulage between Kingswear and Torquay, often hunting in couples to provide the necessary power over the steep intermediate grades.

We have already made the acquaintance of some of the Great Western “articulated” stock, on our journey with the “Birkenhead Diner”, where we found an articulated restaurant car set in use. But here at Kingswear we see awaiting us a complete articulated train, in three “units”, exactly similar to the one that the Great Western Railway ran in the Centenary Procession of 1925, when it was brand new. There is first of all a “triplet”, with a third-class brake, third-class corridor and another third-class corridor, carried on four bogies; then a “triplet”-restaurant car set, with third-class open car, kitchen and first-class open car, again carried on four bogies; and a “twin” at the rear, with first-class corridor and first-class brake, carried on three bogies. Adjacent coach-ends are supported on a large steel casting, under which is pivoted the central four-wheeled bogie, on the lines of the Gresley patent used on the LNER system. The empty weights of the three units are 78,

85 and 53 tons respectively, making a total of 216 tons.

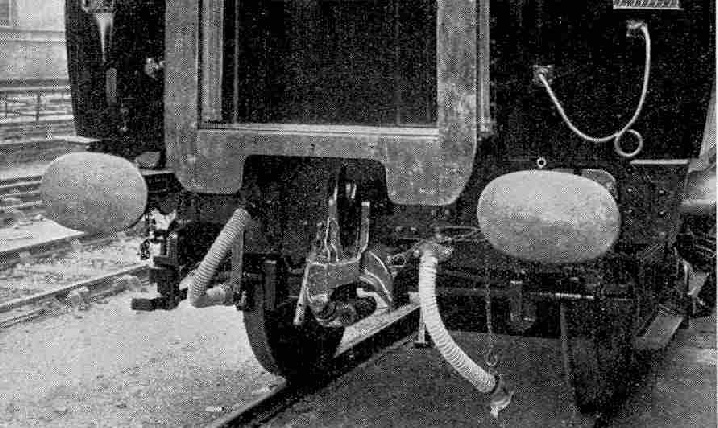

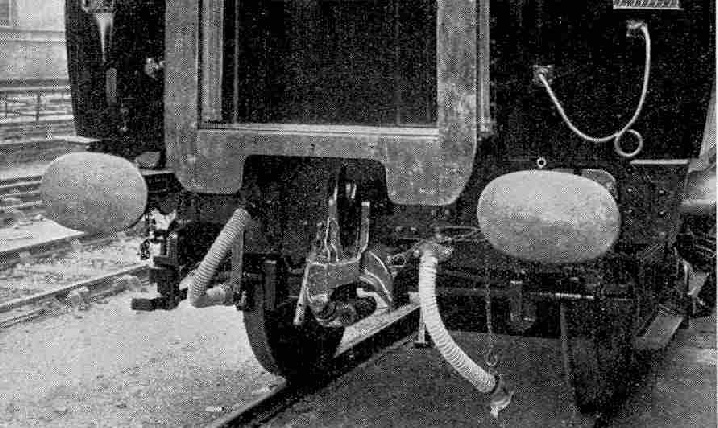

Combined central buffer and coupling on the latest GWR coaches. When in use it rises to the horizontal position, and the side buffers, which are hinged, are dropped downwards.

Again we notice that, where the units are coupled together, ordinary side-buffers and a screw coupling are dispensed with in favour of a central combined buffer and coupling of the Gould type, the coach-ends being rounded in order to bring the two couplings closer together. The two “hands”, as they appear when uncoupled, grip automatically as the coaches are pulled together, and not only provide a coupling of great strength but also hold the whole length of the train rigidly in line, and are one of the finest encouragements to smooth travelling that could be found. The LNER have built up their reputation for perfect smoothness of travel largely on this invention, which they have had in use for nearly 30 years on their East Coast stock, and have now standardised in the building of all main line corridor coaches.

It is at 11.10 a.m. that our boat sheers off from Dartmouth Pier, and 15 minutes later, at 11.25 a.m. the “Torbay Limited” gets away from Kingswear. The speed of the first 14¾ miles of the journey, to Newton, is in striking contrast to that which follows. The time allowance, with three intermediate stops, is, in fact, 48 minutes, and the average speed less than 20 m.p.h.! But there is first a pull at 1 in 57 out of Kingswear up to the high ground of the neck of country separating the Dart Valley from Torbay. Then comes the stop at Churston Junction, where connection is made to and from Brixham; a stop at the rising watering-place of Paignton, and seven minutes’ standing at Torquay. Last of all there is another steep climb out of Torquay, through Torre, as sharply inclined at one point as 1 in 53. As the full summer service has not commenced, too, it is probable that a 2-6-2 tank has had to handle the train as far as Newton Abbot.

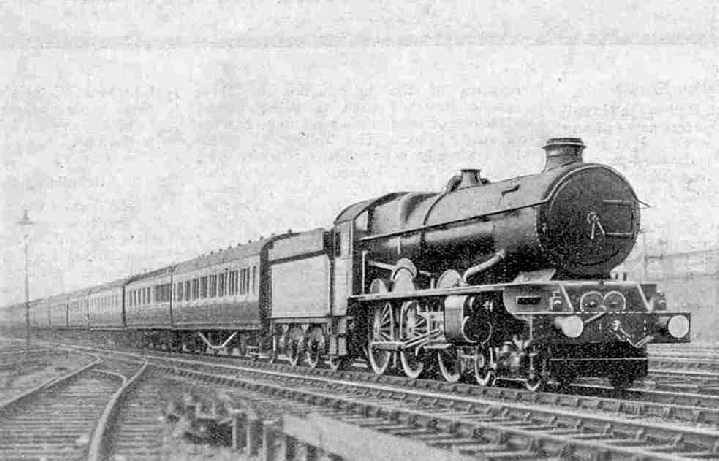

Newton is reached at 12.13 p.m., and we find that the Plymouth and Kingsbridge portions have been in three minutes ahead of us. Probably these will add to the rear of our train not less than five 70-ft coaches, weighing about 175 tons or so, so that our “King”, which will most certainly take his place here at the head of the train, will have behind him a tare load of at least 400 tons, and a gross load reaching the substantial figure of about 425 tons. This is perhaps not excessive, according to Great Western standards, but none of it is to be slipped or detached en route, and it is clearly no feather-weight to whirl up to town at 57 miles an hour all the way. Before we leave Newton Abbot, by the way, we must find time to look at the wonderful manner in which the Great Western authorities have transformed the old, inconvenient and congested station into one of the finest stations on their system, with platforms of tremendous length and width, spacious station buildings, and a most comprehensive lay-out of track, sufficient to meet all developments of train service for many years to come.

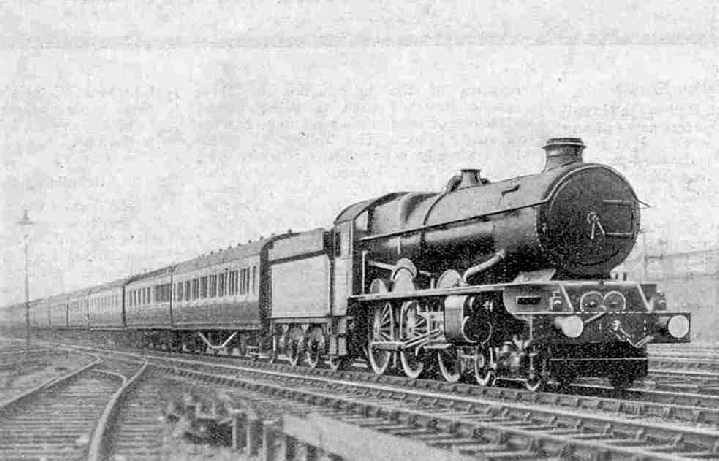

Down “Torbay Limited” express approaching Teignmouth. This section of the line has been blasted out of the rock, leaving on the landward side a magnificent wall of red sandstone.

Punctually to time at 12.20 p.m. we head eastward for Paddington. For the first 20 miles of our journey the course is as near level as makes no matter, first down the tidal estuary of the Teign to Teignmouth, then along the sea-coast to Dawlish Warren, and then up the right bank of the Exe estuary to Exeter. But it is idle for our “King” to gather speed too rapidly, as for a good 10 miles, from this side of Teignmouth to beyond Starcross, the windings of the line round the coast are continuous and sharp, and no higher rate than about 50 m.p.h. is desirable. Successions of tunnels break up the stretch between Teignmouth and Dawlish, cut through the striking red sandstone rock of this coast, which at several points, seen from the line, has been weathered by the sea into singular shapes, such as the “Parson” and “Clerk.” However, we clear Starcross at last, and taking a good draught of water from the Starcross troughs, our “King” picks up to 65 m.p.h. or so, ere the suburbs of Exeter indicate that it is time to close the regulator and slack for running through St. David’s Station. We first thread the “all-over” roofed St. Thomas Station, and a moment later are clearing St. David’s, at reduced speed, noting as we pass, very likely, a Southern express for Waterloo with its engine facing us, as the trains of the two companies pass through St. David’s in precisely the opposite direction.

We have now roughly three hours, or a shade less, in which to complete the remaining 173¾ miles to Paddington. For the next 20 miles the gradients are against the engine. At first the ascent is modest enough. Only for a mile beyond both Stoke Canon and Silverton does it get to as much as 1 in 207 and 1 in 222. Bat as we pass Collumpton the crests of the Mendips are coming in sight, and we get first a two-mile rise at 1 in 154 and then, after a brief drop through Tiverton Junction, 4½ miles up culminating in 2½ at 1 in 115, to Whiteball Box, just beyond Burlescombe. This 20-mile climb will probably not have taken our “King” more than 24 minutes. On the easier stretches speed may rise practically to the mile-a-minute mark, and the last grind up to Whiteball will probably bring us down to about 40 an hour or so. With a shriek the engine plunges into Whiteball Tunnel, under the summit of the ridge, and now it is up to our driver to maintain a mile-a-minute average speed throughout to the point of first slowing down for the Paddington stop.

Wellington bank gives him a good start. Beginning at Whiteball Box, this famous descent extends nearly to Taunton, and is very steep for the first four miles to Wellington Station, including as it does 2¼ miles at an average of 1 in 85. It was on this racing-ground that May 9th, 1904, witnessed the fastest authenticated railway speed that this country has ever known, the 4-4-0 engine “City of Truro” attaining no less than 102½ miles per hour with a mail special from Plymouth to London. We need not expect any speed approaching this, but something well over 80 miles an hour is quite possible, and very fast travelling will continue on past Taunton. It is 31 miles from Exeter to Taunton, and these will have taken us, probably, 33 minutes or less.

Shortly after Taunton our “King” gets a second welcome draught of water, at Creech troughs, and then there will probably follow a slight easing of the speed for the junction at Cogload. This is where we leave Brunel’s old West of England main line, five miles beyond Taunton, for the shorter Westbury route. Notice how the straight original up and down lines have been spread out from each other at Cogload, in order to allow the laying in of a fast-running junction that we can take with perfect safety, even in the facing direction, at 60 miles an hour. From Cogload we cut at speed across the marshes of Sedgemoor and then rise on to the higher ground beyond, nowhere very steeply, threading a long tunnel near Somerton, and joining the old Berks and Hants line, on its way from Weymouth and Yeovil, at Castle Cary.

The character of the line now changes. For miles it is very winding, and for seven miles beyond Castle Cary it is steep as well. With short interposed “steps” of level track, it rises chiefly at 1 in 98 until we breast the signalbox at Brewham, the actual summit being marked by mile-post 122¾. This distance of 122¾ miles is not, of course, by our route, but by the old route from London via Chippenham. As we pass the summit we are but 108 miles from Paddington. The downward run to Westbury is not made at high speed because of the windings, and is broken into by a very severe slack round the curve at Frome; both here and round Westbury curve a reduction to 35 m.p.h. is imperative. Between the two the tender is replenished for the third time, from Westbury troughs. Owing to these various hindrances it is quite possible that the 47¼ miles from Taunton to Westbury may have taken us 51 or 52 minutes, and good going at that, too. If the latter, we have now left but 95 minutes for the remaining 95½ miles to Paddington.

Once again a long rising stretch of line lies ahead - 25i½miles of it; but the only appreciable grades are the six miles up at 1 in 222 from Lavington, and the last six miles up to Savernake, at much the same inclination, broken intermediately by a level strip. The first 7½ miles out of Westbury are, however, virtually level, and allow our driver to top the mile-a-minute rate without difficulty. Up to Patney we then fall to 50, probably, and with a further maximum, very likely over 60, in the dip between Woodborough and Pewsey, we breast Savernake Summit at something a little over 50 an hour, possibly 55. Despite the ascent, our “King” has quite likely run the 25½ miles from Westbury in 27 minutes.

Only 68 minutes now left for the 70 miles to Paddington! Can it be done? With ease; all the hardest work is now over. For the next 31 miles there are nothing but falling grades, and although the winding character of the track prevents our “King” from laying himself out to the maximum of his possible efforts, we can count on an average of 70 miles an hour for miles on end. Water is taken for the fourth and last time from Aldermaston troughs, and seven miles later there comes the slowing for the first of the Reading Junctions - Southcote - ere we sweep round on to the old main line again at Reading West junction. The 34 miles from Savernake have been covered in 31 minutes, and 37 minutes for the remaining

36 level miles is “easy going” by Great Western standards! So we hurry on past Twyford, Maidenhead, Slough - going once again at 70 an hour, probably - Southall, Acton. Then the regulator is closed, and we drift on past Old Oak and Westbourne Park into Paddington, arriving very likely with a minute or two in hand on our schedule time of 3.45 p.m. And we think, as we take our last look at the “King”, that these wonderful Great Western engines must be capable of flying on at these speeds pretty well for ever!

Four-cylinder 4-6-0 locomotive, No. 6005 “King George II”, hauling the up “Torbay Limited”.

You can read more about “The Birkenhead Diner”, “The Cheltenham Flyer”, “The Cornish Riviera Express”, and “The Story of the GWR” on this website.