One of the Most Spectacular Railway Routes in Europe

FAMOUS TRAINS - 40

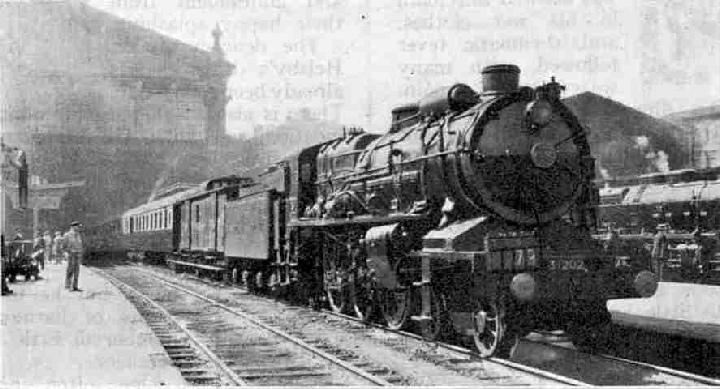

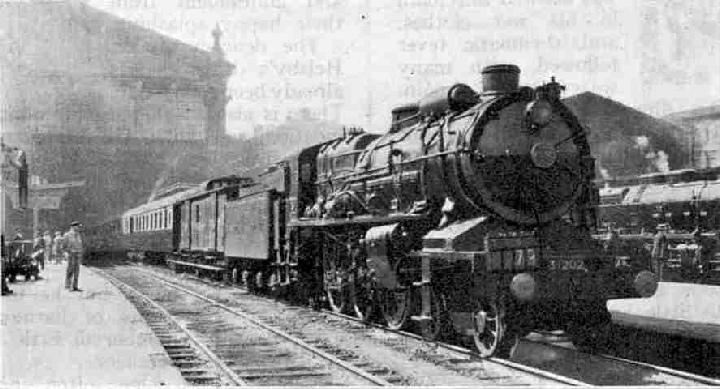

One of the Nord “Super Pacifics”, on the “Golden Arrow” at Paris (Nord). An engine of this type is used to haul the Engadine Express from Boulogne to Laon.

THIS month we are to go for a sightseeing trip over one of the most spectacular railway routes in Europe, rather than to note any exceptional feats of load haulage or speed. Indeed, such feats could hardly be expected over a line with a ruling gradient of 1 in 29, and constant and very sharp curves - over a route where the railway has to travel for 7¾ miles to cover a distance which, in a bee-line, is but 3½ miles, in order to overcome a difference in level, up one mountain valley, of over 1,300 ft. In addition, this has to be done over a gauge of one metre, instead of the 4 ft 8½-in gauge to which we are accustomed. But I am anticipating.

First of all, where is the Engadine? The name has been given to the easternmost big valley in the easternmost Canton of Switzerland. The river, that flows through it - the Inn - -is the one Swiss river whose waters flow to the north-east, to fall into the Danube at Passau in Austria, and travel on ultimately to wash the shores of the Bolsheviks in the Black Sea. But it is not for this reason that the Engadine has become famous. It contains those well-known holiday resorts, St. Moritz and Maloja, which are as popular in mid-winter as in mid-summer,and, in an adjacent valley, the beautiful Pontresina - to carry British passengers to which the Engadine Express is chiefly run. The attraction of the valley lies in the fact of its tremendous altitude. St. Moritz and Pontresina are both roughly 6,000 ft above the sea. and their incomparably pure air is a tonic that annually lures thousands of happy holiday-makers to this playground of Nature. But it is this attractive altitude that at the same time has made so extraordinarily difficult the task of the engineer in giving access to it by rail.

Except, possibly, for the broad valley of the Aar, there is barely a square mile of Swiss soil that could be described as other than mountainous. But if Switzerland generally is mountainous, the easternmost Swiss Canton, the Orisons, is so in a most exceptional degree Roughly one-half of the 2,775 square miles of its area consists of high mountains, for the most part glacier-covered. The remainder is divided into a maze of some 150 valleys, many of them nothing more than wild chasms or gorges, and the most forbidding of territory from the railway point of view. In fact, so difficult was the intervening country, that for many years the Swiss thought it out of the question that St. Moritz could ever be connected by railway with Coire or Chur, the capital of the Canton, served by a lengthy branch of the main Swiss Federal system coming up the Rhine valley. It was left to a German engineer named Hennings ultimately to show them the way.

The railway network known as the Rhaetian Railways now connects Coire directly with St. Moritz, and has reduced what was previously a journey of 13 hours by horse drawn diligence to one of just under 2½ hours in smoothness and comfort by the Engadine Express. It is true that during this period we cover a distance of only 55½ miles, but we shall see presently over what kind of a route this is done. The Rhaetian Railways have extended their tentacles in other directions also. A loop route starts out from Coire alongside the Swiss Federal line down the Rhine Valley to Landquart, then turns eastward into the deep valley known as the Prattigau, through an extraordinary natural gateway in the mountains rightly called the “Klus”, or key. Ascending this valley to Klosters, it then climbs high up the mountain side and over the ridge into the valley in which is situated another famous resort - Davos —whence it descends to join the main route previously mentioned ere the ascent of Valley is begun.

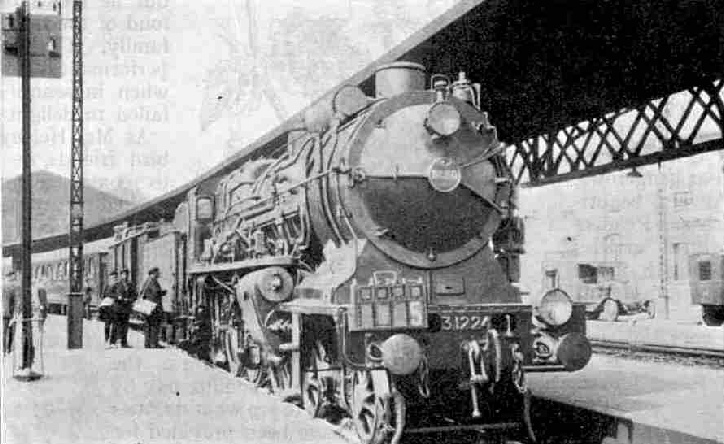

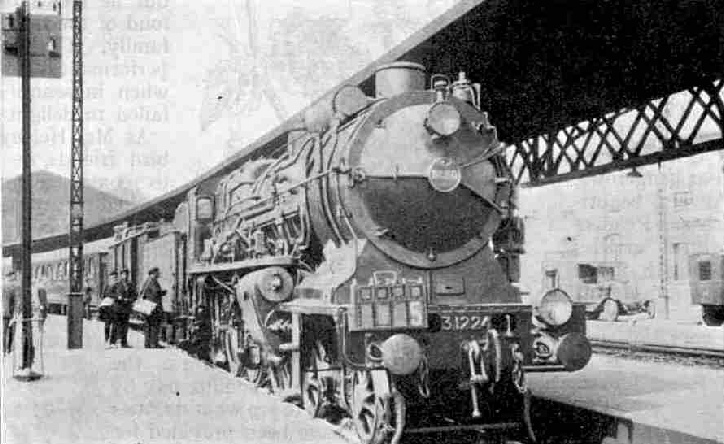

Super-Pacific 4-cylinder compound express locomotive No. 3.1224 Chemin de Fer du Nord of France at Filisur.

Another branch ascends the valley of the Vorder Rhein - one of the sources of the great Rhine - from Coire to Disentis, whence it is continued by the newly-opened Furka-Oberalp Railway over the 6,720 ft Oberalp and 7,100 ft Furka Passes through Andermatt to Brigue, at the mouth of the Simplon Tunnel, in the Rhone Valley. It is thus now possible to make a journey by metre-gauge train halfway across Switzerland, in a through coach from St. Moritz to Brigue; and, more extraordinary still, from a valley whose waters are flowing to the Black Sea, through several valleys whose waters will reach the North Sea, into one that drains into the Mediterranean!

The third Rhaetian branch runs down the Inn Valley northeastward from St. Moritz to the well-known spa of Schuls-Tarasp, whence it may be extended some day across the nearby Austrian frontier to join the Arlberg main line at Landeck.

Altogether the Rhaetian Railway authorities, with rare enterprise, have laid just over 170 miles of railway through this terribly difficult Canton. It is entirely of metre gauge, which, although at the expense of speed and earning capacity, makes it possible to use sharper curvature, so that cutting and embanking can to some extent be kept down by the track closely hugging the irregular mountain sides. Even so, much heavy engineering work has been necessary, including 81 tunnels - one of them 3¾ miles in length and at an altitude of 6,000 ft above the sea - and 407 bridges or viaducts, some of them of astonishing size.

But before we can travel on the narrow-gauge Engadine Express we have to see something of the standard gauge Engadine Express that is to carry us luxuriously across Europe from Boulogne to Coire. We must therefore get ourselves and our baggage to Victoria in good time to catch the “14.00” boat express for Folkestone. Our British division of the day into two halves, instead of the sensible Continental 24-hour system of reckoning time, makes this two o’clock in the afternoon. A Southern “King Arthur” will hurry our substantial train - consisting of 6 or 7 corridor coaches, probably three Pullman cars, and one or two brakes - down to Folkestone junction, where we shall run through into the sidings beyond the station. Here a couple of diminutive 0-6-0 tanks will attach themselves to the back of the train and lower us cautiously down the 1 in 42 gradient to Folkestone Harbour Station, where we are due at 3.40 p.m. We shall hope to find the Channel in a kindly mood, and after about an hour and a half we ought duly to discover ourselves alongside the quay at Boulogne, whence we pass through to our waiting Swiss express.

It is a “Blue” train, and so will immediately arouse the interest of every Hornby Railway Company enthusiast. Now that the “Blue Train” proper (from Calais to the Riviera, which is run on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays only), has become a “super-Blue Train” with new and very magnificent rolling stock, the familiar blue sleeping cars are being used on many other services, this one included. We note with pride, as we did in the case of our “Golden Arrow” journey, that, when the French want the finest rolling stock that can be built, they come to England for it, as the makers’ name-plates on the coaches bear witness. Our train is composed entirely of sleeping cars, with a big restaurant car and one or two vans, and the little white destination boards on the sides of each car provide an interesting study.

We soon find our own cars, labelled “Boulogne - Coire”; next to them are cars bearing the inscription “Boulogne - Arlberg -Vienne”, which will keep us company until we are within 16 miles of Coire. Then, again, there are through sleeping cars for Interlaken, in the Bernese Oberland, which we convey to Belfort, in Eastern France, where they leave us to cross the frontier at Delle, making straight for the Swiss capital of Berne, while we are running on to Basel. Not only is our express first-class only, but a handsome supplement is charged in addition for the use of the palatial sleeping cars, so that this is not going to be a cheap journey. But a trip by a Continental train-de-luxe is certainly the essence of comfort.

The first train away from Boulogne after the arrival of the boat is the ordinary express for Paris, which leaves at 5.53 p.m. We are due to start nine minutes later, at 6.2 p.m. There is little doubt that the engine of our heavy express, whose formation in the height of the season may turn the scale at anything from 500 to 600 tons, will be one of the famous super-“Pacific” type of the Chemin de Fer du Nord. The amazing exploits of these engines have been described more than once in these columns. Suffice it now to say that with 500-ton trains they constantly maintain average speeds of round about 55 mph up continuous 1 in 200 gradients - like the climb of the LNER main line from Wood Green to Potter’s Bar on the north side of London - and travel along the lengthy stretches of level track between Etaples and Amiens for mile after mile at 70 miles an hour. Yet each of these engines weighs, without tender, 96 tons, or almost exactly the same as one of the “super-Pacifics” of the latest “Flying Scotsman” type on our own London and North Eastern Railway.

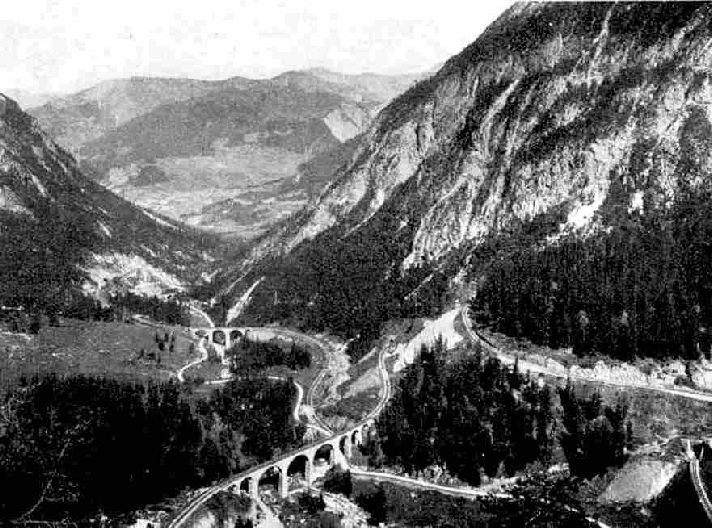

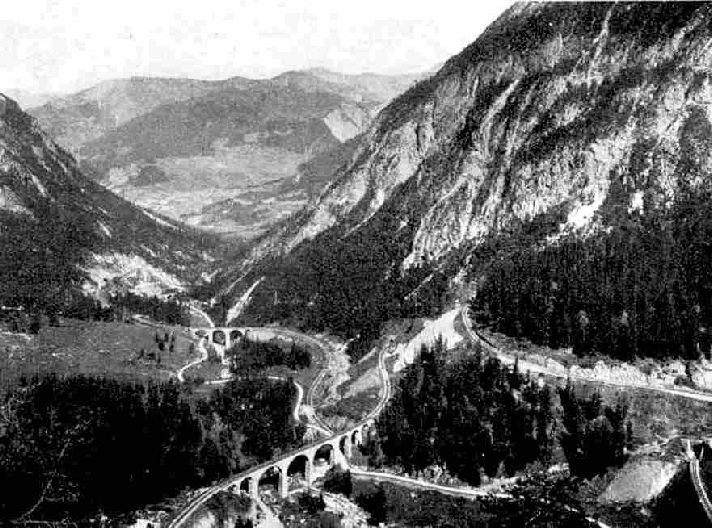

The Engadine Express ascending the spirals in the Aibula Valley, Rhaetian Railways.

We have travelled previously over the main line of the French Northern Railway, when we flew from Calais to Paris by the “Golden Arrow”. After passing slowly through the “Ville” station at Boulogne, we join this route at the “Bifurcation d’Outreau”, or Outreau Junction, as we should call it. We then follow the same course through Etaples and Abbeville to Amiens, where we diverge to the north, as we are to avoid Paris altogether by taking a more northerly route through Laon and Rheims. The most interesting features of this part of the journey are the remarkable feats of reconstruction that have been carried out by the Chemin de Fer du Nord authorities since the Great War. Here we are passing through the heart of the Western Front where, when hostilities ceased, little vestige of any main lines of railway remained. Now all the bridges have been re-erected, all the tracks relaid, all the stations and depots re-built, and to the traveller it is like passing through a new railway world, all equipped in the latest and most modern fashion.

During this part of the journey we have been dining very comfortably in the palatial British-built restaurant car, and the next part of the proceedings will be to get to bed, as we have a great deal to see to-morrow and must keep ourselves as fresh as we can. Before retiring, however, we must see the change of engines at Laon, as here we cross a railway “frontier” - from the system of the Nord to that of the Est. Our new locomotive is probably of the 4-6-0 type, the Est management never having favoured the “Pacific” type to the same extent as the other French railways, though they have a few of a standard design that were built for general French railway use just after the War. Laon is reached exactly at 9 pm, and we leave again at 9.8 pm. Owing to its weight, this train is not timed at so high a speed across France as the special Swiss night express, in connection with the 4 pm service from London, which is booked to average over 50 mph, stops included, from Calais across to Belfort, a total distance of 435 miles.

While we are sleeping soundly in our comfortable berths we are hurried on through Rheims to Chalons, which is the next stop, and then to Chaumont and Belfort, where we drop the Bernese Oberland section of the train and exchange our Est locomotive for one of the Alsace-Lorraine Railways, over whose territory we have now to pass. One of the benefits of the war to the traveller is that it is no longer necessary to pass through a corner of Germany between Belfort and Basel, so that the customs examination in the middle of the night at Petit-Croix is fortunately a thing of the past.

With one more call, at Mulhouse, we pass on to Swiss territory and find ourselves in the great Central Station at Basel at 5 o’clock in the morning, having travelled 460 miles from Boulogne. Over an hour is allowed here, for the Customs officials have to visit us - though we need have no fear, as the Swiss douaniers are always the embodiment of gentleness and courtesy in their attentions. Through sleeping cars for Vienna and Coire have to arrive from Paris, to be attached to our train. So it is 6.10 in the morning before we get away again, feeling, no doubt, quite ready for the enticing breakfast of crisp rolls, real Swiss butter and steaming coffee that is served in our restaurant car on the next stage of the journey.

This is at the outset up the wide Rhine valley, but presently, at Stein, we turn up a branch valley, tunnel for 1½ miles under the crest of the ridge at Effingen, and drop down to the valley of the Aar, with our first distant view of the snowclad Alps away to the right. Crossing the rapid river, we pass through the large station at Bragg, where we are joined by an important main line from Berne, through Olten; then, passing the spa of Baden, we approach the outskirts of a great city. Drawing slowly into a large terminal station, we find we have arrived at Zurich, the biggest and most important town in Switzerland, with 207,000 inhabitants. We have travelled from Basel to Zurich behind a powerful electric locomotive, and have taken 76 minutes for the steeply-graded journey of 55½ miles.

At Zurich our train is reversed. Electrification of the main line from Zurich to Coire has now been completed. Last time I travelled over the route it was only partly electrified, with the result that our heavy train went out with a steam locomotive as train engine, piloted by an electric, locomotive - a singular haulage combination indeed. After 17 minutes’ wait we re-start at 7.43 am, and, making a wide circuit of the city, we find ourselves, three miles after starting, on the south-west shore of the Lake of Zurich which, with its 25 miles of length and 2½ miles’ maximum width, is one of the largest in Switzerland. We skirt the lake as far as Pfaffikon, and then join at Ziegelbrucke the line that has come along the opposite bank. Making straight for the mountains we then come into sight, at Weesen, of the beginning of another large lake, called the Wallensee - pale-green in colour; and we notice that the opposite side, as we skirt the shore, consists of sheer precipices dropping straight into the water. We leave the lake at Wallenstadt, and soon afterwards we strike the Rhine Valley once again, when the train stops at Sargans. For the 56¾ miles from Zurich to Sargans the timetable allows 84 minutes, but it must be remembered that the bulk of the distance is single-line.

At Sargans we are to lose from the rear of the train the portion going over the Arlberg to Innsbruck and Vienna. This goes down the Rhine Valley for a short distance towards Lake Constance, whereas we are to turn southward up the valley. So it is with a comparatively light train that we leave again at 9.11 am on our short 16-mile run to Coire. A stop is made at Ragaz, a famous spa. The next stop is at Landquart, where we have our first sight of the Rhaetian Railways, and passengers for Klosters and Davos bid us their adieux; and at 9.38 am we find ourselves in the handsome new station at Coire, 15 hours 36 minutes after leaving Boulogne.

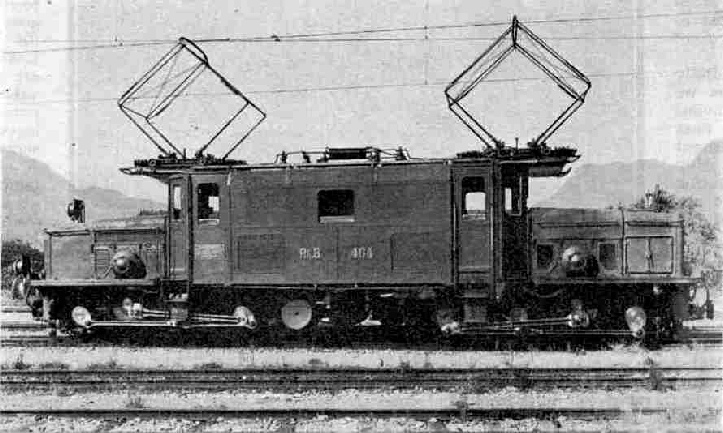

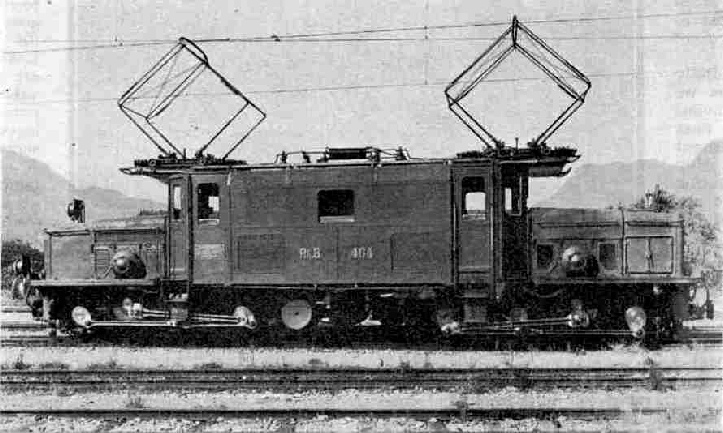

0-6-6-0 Electric locomotive, used for hauling the Engadine Express over the Rhaetian main line from Coire to St. Moritz.

We have now to say good-bye to the luxurious blue cars that have brought us 587 miles across Europe, and to transfer ourselves and our baggage into the neat olive-green coaches of the Rhaetian Railways for the remaining 55½ miles to St. Moritz. Towards Coire we have been gradually mounting, our altitude being now 1,925 ft above the sea; but what is this to the 5,830 ft altitude of the station at St. Moritz, to which we have now to attain?

Eighteen minutes are allowed by the authorities for the transfer at Coire, and at 9.56 am we set out, once again electrically hauled, toward the highlands of the Grisons. There is no booked stop ahead of us for just over two hours, during which we shall cover 51 miles; and in view of the gradients to be surmounted, the average scheduled speed of 25 miles an hour is remarkably high. At first we see little of note from the engineering point of view Reichenau-Tamins marks the junction of the two main sources of the Rhine - the Vorder Rhein and the Hinter Rhein, the latter of which we cross by a steel bridge just after passing the junction station. The Disentis line, which is going up the Vorder Rhein Valley, now leaves us on the right, and we climb high up above it until we turn suddenly inward and find ourselves in the Hinter Rhein valley.

No gradient on this part of the route is steeper than 1 in 40. The valley is broad enough until we approach the town of Thusis, where the mountains appear to close in all round us. From the depths of an amazing chasm known as the Via Mala - with side's in places 1,700 ft in height, and yet so narrow in parts that you could almost stretch your hands from one wall to the other there issue the waters of the Hinter Rhein. Clearly there was no way of laying a railway in this direction, apart from very extensive tunnelling.

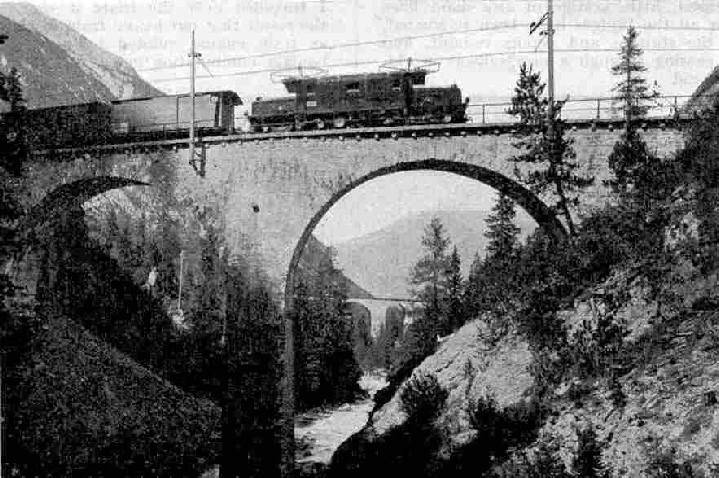

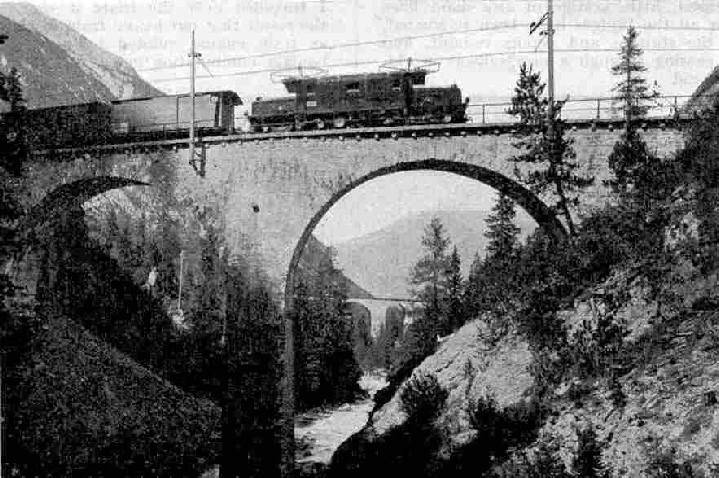

For over seven years, in fact, the railhead of the Rhaetian Railways remained at Thusis, and the remainder of the journey to the Engadine had to be made by coach, until the engineer Hennings had devised Ids astonishing location of the line tip the Albula Valley, and had opened the route through to Celerma in 1903. From Thusis he swung round left ward into the Schyn Ravine, deep in the bottom of which the Albula tempestuously forces its way to join the Rhine. We climb high up the left bank, with glimpses between many tunnels of the foaming torrent, far down a precipitous slope below us. Emerging into more open country at Solis, Hennings found it necessary to carry his line across to the opposite bank, and this he did by the great Solis Bridge. Founding his main piers on the rock on both sides of the gorge, lie built his beautiful masonry arch, carrying the rails 292 ft above the water. The Wiesen Bridge, which figures in one of the illustrations, is of a very similar type, save that in this case the foundations had to be carried almost down to the water-level, 289 ft below the rails. The span of the latter remarkable arch is 80 ft.

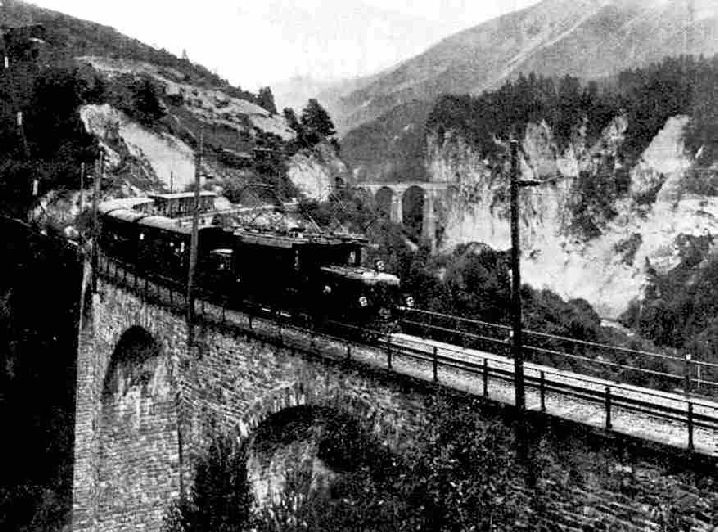

Wiesen Bridge the other section of the Rhaetian main line, coming up from Landquart through Davos to join us at Filisur. Before the two sections can effect a junction, however, we have also to jump across the same Landwasser River - tributary of the Albula - which we do by means of the Landwasser Viaduct. We shall agree that this is one of the most breathless structures it has ever been our lot to cross. Curved sharply round on a radius of 328 ft, rising on a gradient of 1 in 40, and 213 ft above the floor of the valley, the last arch of the viaduct on the opposite side is built directly into the face of a precipice, and we are ushered straight into the blackness of a tunnel the moment we have crossed - a most singular experience. We have, on reaching Filisur, travelled 31½ miles from Coire and reached a height of 3,550 ft above the sea.

Climbing has now to begin in serious earnest. For the final ascent of the Albula Valley a gradient of 1 in 40 is of little use, and the figure steepens to “35 in 1,000”, as it is reckoned abroad, or about 1 in 29. This climbing naturally has the effect of reducing our speed somewhat, but we still find our powerful locomotive travelling upward at a steady 20 miles an hour. Just beyond Filisur we enter a spiral tunnel, and on emerging, at an altitude higher by 80 ft, look down on the stretch of line over which we were running just previously. Steadily ascending, with the Albula for most of the distance far below us on the right, seen through a dense pine forest, we approach the prominently situated village of Bergun; in 5½ miles from Filisur we have climbed 960 ft.

Now the most tortuous part of the journey lies immediately ahead. Preda is but 3½ miles away, in a bee-line, but it is another 1,335 ft above us, and we are going to cover 8¼ miles in order to get there. First of all, by the aid of a couple of curved tunnels at the two “elbows”, we describe an immense double bend on the rocky slopes above the village. Corning back into the main valley, high above the Albula, we continue climbing until the bed of the rushing stream has nearly overhauled us, when we cross it and describe a completely spiral tunnel in the opposite mountainside. But a short distance afterwards we recross the stream, and enter a second spiral tunnel, following which we double over the stream and double back yet again - by masonry viaducts in each case - to enter a third spiral tunnel immediately above the second! These turns and twists are so bewildering that the traveller soon loses his bearings completely. At last we reach Preda, 5,880 ft above the sea, and the railway, as though exhausted with its efforts, seeks refuge in a tunnel.

The remarkable spiral location of the Rhaetian Railways main line between Bergun and Preda.

If you look out of the carriage window in a forward direction just before the tunnel is entered, you will see right through it, as it is perfectly straight from portal to portal. But you will be pardonably astonished as you travel through to find that it is no less than 3¾ miles in length. You can well understand that boring so long a tunnel at this tremendous altitude was no easy task. The temperatures were very low, and some of the worst difficulties arose from the tapping, at three different points, of powerful springs of very cold water, which between them held up the work for 15 months. For over a mile the rock pierced is so hard that it has not been necessary to line the tunnel here with masonry.

It takes us about ten minutes, or slightly less, to pass smoothly through, and on emergence we find we have come out into another world. We have passed from the watershed of the Rhine into that of the Danube. The luxurious vegetation and dense forests of Western Switzerland give place to a comparative barrenness. In the crystal-clear air the great giants of the Roseg group of Alps, over 13,000 ft in height, stand out prominently across the wide valley of the Inn. We stop first at the junction of Bevers, exactly at midday; here is detached a through coach that is going down the Lower Engadine to Schuls-Tarasp. Four minutes later we are at Samaden, where the portion for Pontresina - 3¼ miles away, up the valley to the left - parts company with us. A brief stop at Celerina, and at last, at 20 minutes past twelve, in excellent time for lunch at our hotel, we are at rest in the fine station at St. Moritz, alongside the lake, and in the heart of the noblest scenery in the Grisons.

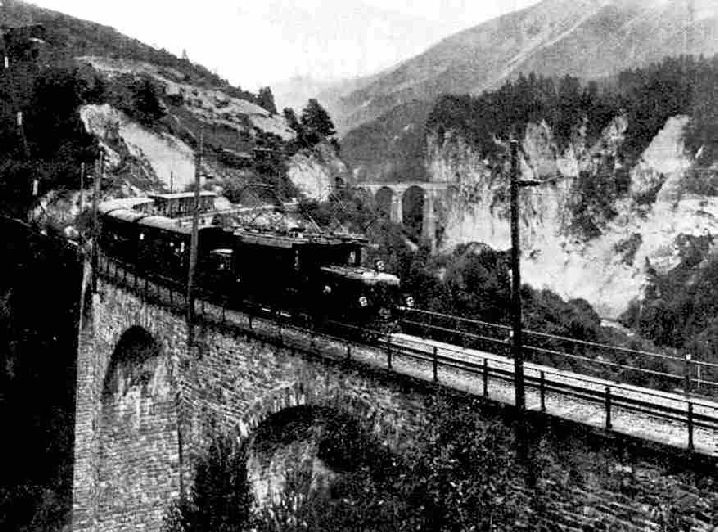

The Engadine express crossing Schmittentobel Viaduct, Rhaetian Railways. The Landwasser Viaduct is seen in the background.

You can read more about “The Fleche d’Or”, “The Glacier Express” and “Through the Bernese Alps” on this website.