Rapid Service to Britain’s South-Western Counties

FAMOUS TRAINS - 13

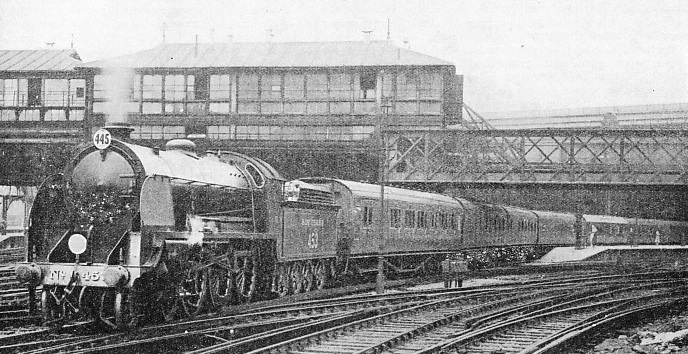

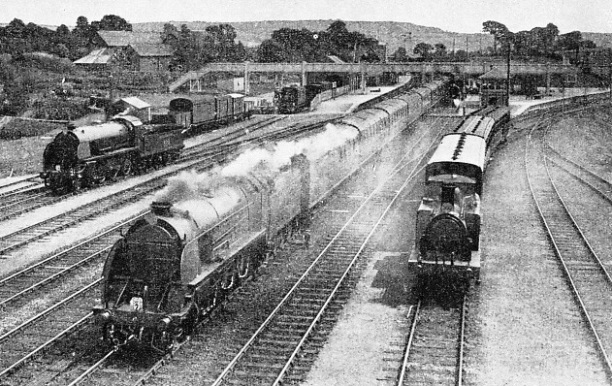

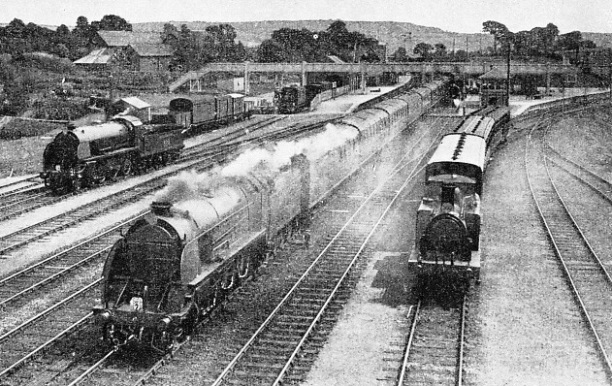

LEAVING WATERLOO STATION. The “Atlantic Coast Express” daily departs from London at 11 am for the south-west of England. The train comprises nine sections, which serve the Ilfracombe, Torrington, Plymouth, Padstow, Bude, Sidmouth, Exmouth and Exeter districts. Two restaurant cars, detached at Exeter, form the ninth section. The average weight of the train behind the tender is just over 400 tons. During the height of the summer holiday season the train is so popular that it is run daily in two parts (four on Saturdays).

FOR many years past, back into London and South Western days, an express has left Waterloo daily at eleven o’clock in the morning. But it is only since the formation of the Southern Railway, and the coming into fashion of the attractive habit of naming trains, that this popular train has acquired the dignity of a title. The choice of “Atlantic Coast Express” is, moreover, a particularly happy one. Not only does this train spread itself over a considerable length of the shores of the Atlantic before the daily journeys of its various sections are completed, but also the initial letters of the name form the appropriate word “ACE”. The Southern Railway has not neglected to use this telling detail in its advertisements of the service - the “Southern Railway Ace”.

Now that the “Cornish Riviera Express” of the Great Western Railway is run in two portions daily throughout the year - the first portion being called the “Cornish Riviera Limited” and the second (in summer) the “Cornishman” - the “Atlantic Coast Express” has become the most multi-portioned train in Great Britain. Nine different sections are comprised in its daily formation, each making for a different destination. Each one of them, except the Ilfracombe section, normally consists of one coach only - a composite brake coach containing two first-class, four third-class, and a guard’s and luggage compartment.

Next the engine comes what might be termed the main section of the train, consisting of three coaches for Ilfracombe - two third-class brakes and a first and third-class composite between them. Keeping company with the Ilfracombe portion as far as Barnstaple is the coach for Bideford and Torrington. Next behind that are coaches for Plymouth, Padstow, and Bude, detached from the main train at Exeter, and then running together as far as Okehampton, high up on the slopes of Dartmoor, where the Plymouth coach turns southward, and the Bude and Padstow coaches continue to the west. The two restaurant cars also are detached at Exeter.

At Sidmouth Junction two coaches come off, one for Sidmouth and one for Exmouth. These will run together as far as Tipton St. John's, after which the Exmouth coach will travel round the coast through Budleigh Salterton into Exmouth. Last of all there is a coach detached at Salisbury for all stations between Templecombe and Exeter.

The various portions are, therefore, for Ilfracombe, Torrington, Plymouth, Padstow, Bude, Exeter, Sidmouth, Exmouth, and Exeter “slow” - twelve vehicles in all, with a tare weight of about 388 tons, or, with passengers and luggage, all average of a little over 400 tons behind the tender trom Waterloo to Salisbury and of about 370 tons from there to Sidmouth Junction.

During the height of the summer scason, of course, the traffic to the coast resorts of Devon and Cornwall is so heavy that one train could not possibly carry it all. The Ilfracombe, Bude, and Padstow portions then run separately, at 10.35 am from Waterloo, calling only at Salisbury between London and Exeter, which is reached in 3 hours 12 minutes, notwithstanding the distance of 171¾ miles, the exceedingly heavy gradients, to which reference will presently be made, and the five minutes spent standing in Salisbury Station. On summer Saturdays further expansion takes place, and independent trains are run at 10.35 am for Ilfracombe and Torrington, at 10.45 for Padstow and Bude, at 11 for Plymouth, and at 11.45 for Exmouth and Sidmouth.

As with previous “Famous Trains” which have come under consideration in this work, the best appreciation of the “Atlantic Coast Express” is obtained by making a journey on it. The opportunity is the more valuable as it makes possible a review of the extensive railway system which was built and operated by the late London and South Western Railway, now the Western Section of the Southern Railway, and the largest ot the three constituent companies of this group.

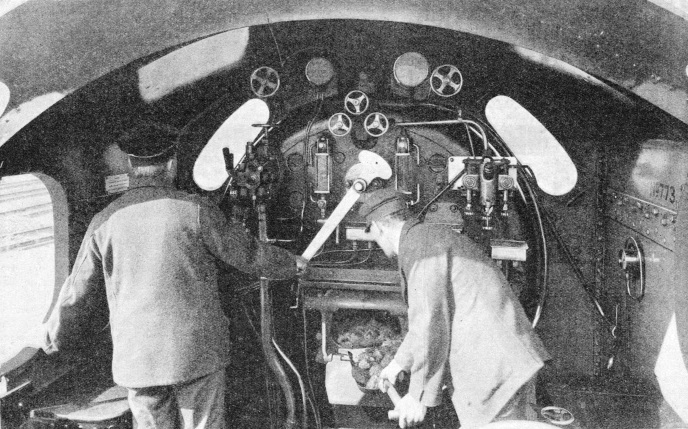

Out of Waterloo the line ascends for a short distance on a 1 in 141 gradient, and the engine which has brought the coaches to the platform assists the train engine by pushing in rear for a hundred yards or so out of the station. As far as Salisbury the "Atlantic Coast Express" is usually worked by one of the four-cylinder 4-6-0 locomotives of the “Lord Nelson” class - the largest and most powerful express cngines on the Southern, although two-cylinder 4-6-0 “King Arthurs” are sometimes used. There is a difference of only two tons between the weight of the two types without their tenders.

A Flying Junction

The first stage of the run, from Waterloo to Salisbury, measures 83¾ miles in length, and the schedule of 87 minutes leaves no time to spare. For the first fifty-one miles the work is mainly “against the collar,” with little or no respite in the matter of level track, and no down-grades of note. After the downward sweep from beyond Basingstoke (48 miles) to Andover (66½ miles), there is a steep rise to be mounted to Grateley (72¾ miles) - all within the compass of a booking at 57.8 miles per hour from start to stop. For twenty miles from the start, however, up the Thames Valley, the line is fairly level, with but gentle ups-and-downs. As the main line of the Central Section (from Victoria) swings across the tracks of the Western Section, descending to make the immense width of trackage - running lines and sidings - immediately to the east of Clapham Junction (4 miles), the “Atlantic Coast Express” has attained a speed of fifty miles an hour or slightly over. The line now rises on easy gradients to Wimbledon (7¼ miles), and is dead level from there to Surbiton (12 miles), giving the locomotive its first opportunity of getting above the mile-a-minute rate.

At Hampton Court Junction (13¼ miles) the down line to Hampton Court leaves the main line by means of a flying junction, directing attention to the care with which the late London and South Western Railway brought practically all its branches between Wimbledon and Basingstoke into the main line by either flying or burrowing junctions. This was to avoid any interference on the part of the slower traffic on the outer lines with the fast trains, which use the centre lines of the four-tracks main line. Junctions of this description may be seen at Raynes Park, Malden, Hampton Court Junction, Pirbright (near Brookwood), Sturt Lane Junction (near Farnborough), and Worting, where the main lines to Southampton and to Salisbury part company.

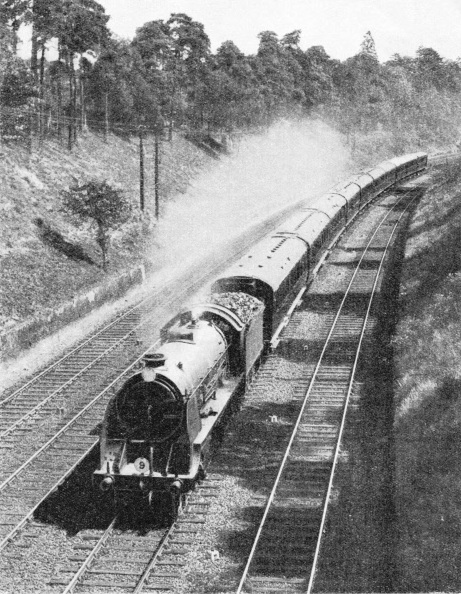

IN CLAPHAM CUTTING, between Clapham Junction and Earlsfield. Not far beyond Clapham Junction, four miles out of the terminus at Waterloo, the “Atlantic Coast Express” attains a speed of fifty miles an hour or over. The “ACE” is generally hauled by a “Lord Nelson” class engine, one of which is seen in front of the express, above, as far as Salisbury, Wiltshire.

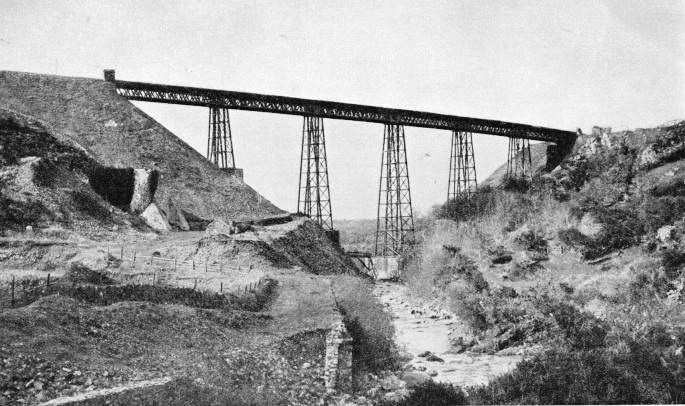

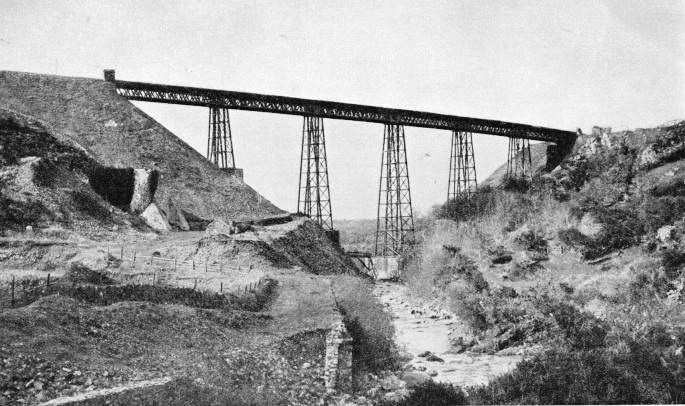

MELDON VIADUCT, near Okehampton (Devon), is the highest structure on the Southern system; it has a maximum height of 113 ft and six spans of 86 ft 6 in. in length. Over this viaduct passes the Plymouth section of the “Atlantic Coast Express”. On the Exeter-Plymouth line there are long stretches of 1 in 75 or 1 in 80 gradients, and the line has to climb to 950 ft above sea-level.

Past Weybridge (19¼ miles) there is a slight descent, and speed may here rise to sixty-seven or sixty-eight miles an hour, in preparation for the decided climb that immediately follows. As the express thunders alongside Brooklands Racing Track, it is quite possible that the “Lord Nelson” at its head may suffer the indignity of being handsomely outpaced by a racing car which is being tested. Steam has no cause for shame, however, when it is remembered that the steam locomotive is hauling a train of some four hundred tons’ weight behind the tender, whereas the racing car has been reduced in weight to the minimum that will safely house the engine, and carries no more than two persons at most.

The “Atlantic Coast Express” now passes Woking - the important junction for Guildford and Portsmouth, 24½ miles from Waterloo. Beyond the station the “Lord Nelson” locomotive is hard at work up rising grades - 10½ miles in length - which gradually steepen from 1 in 388 to 1 in 298, and breasts the summit of the first section of the climb at mile-post 31, in a deep cutting between Brookwood and Farnborough. Throughout the 23½ miles between Woking and Basingstoke the four tracks are spanned by a succession of signal bridges carrying one of the first installations of fully automatic electro-pneumatic signalling to be made in Great Britain. It is only at the stations and junctions over this length that manual signalling is used.

Southern’s Highest Speeds

The Woking-Basingstoke stretch daily witnesses some of the highest continuous speeds developed on any part of the Southern Railway system. These are, of course, in the opposite direction, and averages of well over seventy miles an hour, continued from Basingstoke through Woking as far as Weybridge and Surbiton, are common. Beyond Surbiton the congestion of suburban traffic compels a reduction to a more cautious rate of travel. From Brookwood through Woking to Byfleet sustained speeds of over eighty miles an hour are not infrequent, though the maxima may not rise to quite the same extremes as over the steep banks of the West of England switchback which the “Atlantic Coast Express” will presently reach. From mile-post 31 the line continues fairly level for fifteen miles, through Winchfield to just beyond Hook (42½ miles), after which climbing recommences more steeply than before. For five miles past the important junction of Basingstoke (48 miles), and onwards to Worting Junction, the gradient is a steady 1 in 249. Assuming that we passed mile-post 31 at fifty miles an hour or slightly over, and attained sixty-five to sixty-eight on the level beyond, if we top Worting summit at fifty miles an hour, we shall do well.

Worting, although a lonely box in the open country, is one of the most important junctions on the system. For here the West of England main line diverges from the original London and Southampton Railway that later became the London and South Western. The up line from the Southampton direction is now brought in by a fly-over line; down trains for Southampton pass at Worting on to what up till now has been the down slow line, and the divergence is at Battledown, fifty-one miles from Waterloo. Here the four tracks from London come to an end and converge to two. A word may be spared here for the Southampton route, which has many features of interest. The line continues to mount gently until it reaches a tunnel known as Litchfield, from which there is an unbroken descent, averaging 1 in 252, for seventeen miles past Winchester to Eastleigh - a magnificent racing-ground, indeed, if drivers choose to make use of it for speeding. At Eastleigh are situated the large and well-equipped locomotive, carriage, and wagon works of the late LSWR, which gave birth to the "Lord Nelson" class locomotive at the head of our train, and to the “King Arthur” that will be used over a later stage of the journey.

Eastleigh is 73½ miles from Waterloo, and six miles beyond lies Southampton, where the great docks, the property of the Southern Railway, form one of the most valuable assets of that company. passing round a sharp curve at Northam, trains reach the Central Station, which has recently been rebuilt as a modern station with four platforms, in place of the original two. Only one daily express in either direction has the distinction of passing through Southampton without stopping. It is the "Bournemouth Limited", leaving Waterloo for Bournemouth at 4.30 pm, and Bournemouth Central for Waterloo at 8.40 am. Both make the run of 108 miles between London and Bournemouth in two minutes under two hours.

Other expresses, calling only at Southampton Central, require about two hours ten minutes. In the down direction these fast trains for Southampton and Bournemouth leave London at thirty minutes past the hour practically throughout the day, this being one of the features of the systematic time-tables introduced all over the Southern Railway system after the grouping.

Across Salisbury Plain

In addition, many special express trains, the principal of which include Pullman cars, run between Waterloo and Southampton Docks in connexion with the steamer sailings. These trains are run alongside the steamers, and the busiest times are experienced during the summer season, when numerous crowded cruising steamers require to be catered for in this way. At times a dozen or more large liners, either inward or outward bound, require special connecting services, several special trains being needed to supply accommodation for the passengers and mails to or from one big liner alone. But to return to the “Atlantic Coast Express”.

Soon after passing Worting, the engine is notched well up, and the regulator partly closed, for a long and easy stretch of line lies ahead. Past Overton (55½ miles), near which for many years past the paper for Bank of England notes has been manufactured, the gradient is gradual, but it steepens to 1 in 194 from Whitchurch (59¼ miles) to Hurstbourne (61¼ miles), and there is a further three-miles drop, at 1 in 178, before Andover (66½ miles), on which a maximum speed of eighty miles an hour is quite probable. The impetus from this descent is useful in helping the train up the rise to Grateley (72¾ miles), the last three miles of which mount at 1 in 165, and bring the speed down to fifty miles an hour or less.

Over the chalk downs the line descends again, as steeply as 1 in 140 and 1 in 169 for four miles, through Porton (78¼ miles). This tempting length often produces a final “eighty” before the lender spire (404 ft) of Salisbury Cathedral - the tallest in England - is seen ahead. This heralds the shutting off of steam, and the slowing down for the important junction of Salisbury. No regular Southern Railway express, either down or up, has ever omitted the Salisbury call; and though there have been brief summer periods during which engines have worked through between London and Exeter, changing their crews at Salisbury, it is the general practice to change engines there as well.

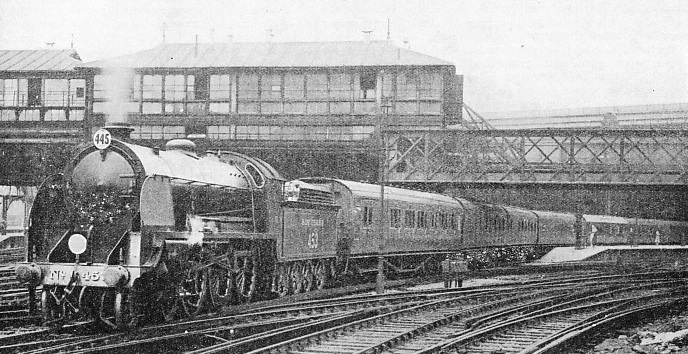

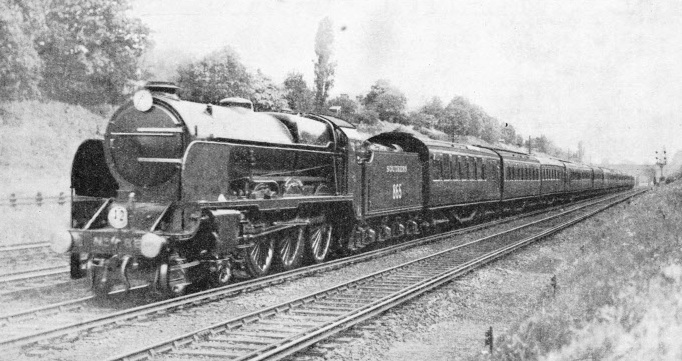

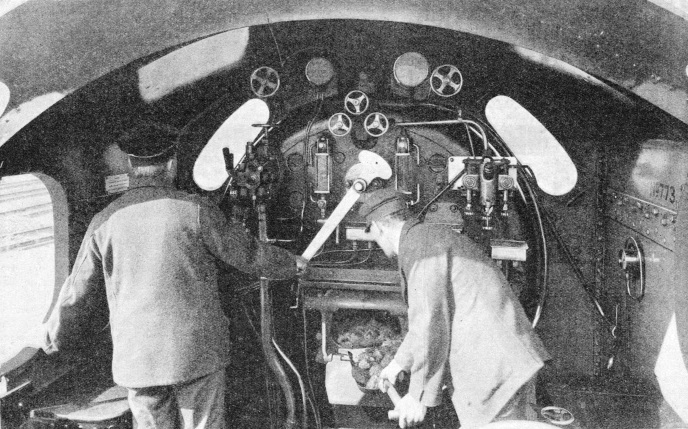

ON THE FOOTPLATE of a “King Arthur” class locomotive. The “Atlantic Coast Express” is sometimes hauled from Waterloo to Salisbury by one of these powerful 4-6-0 two-cylinder express engines which, weighing eighty-one tons, without the tender, are only two tons lighter than a “Lord Nelson”. From Salisbury, where locomotives are changed, a “King Arthur” class engine generally hauls the express to Exeter.

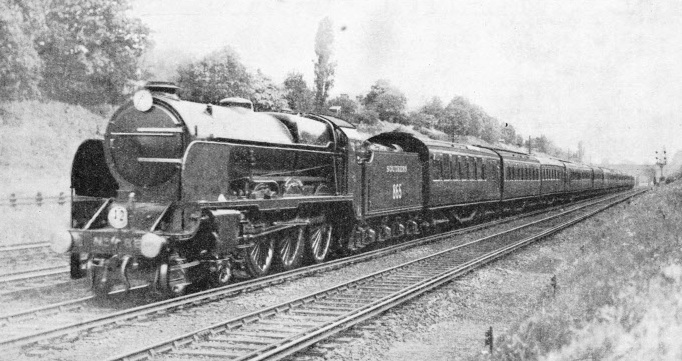

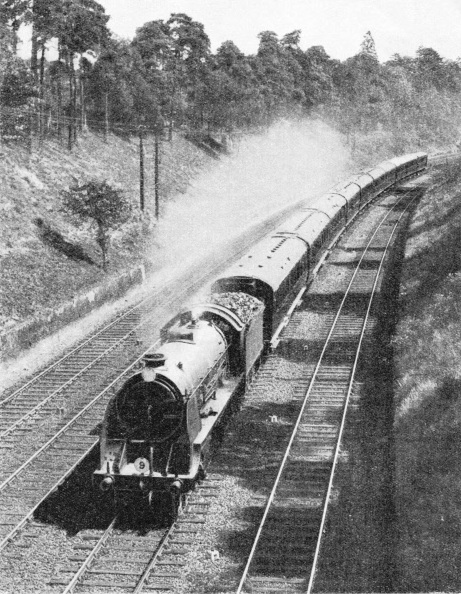

NO RESTRICTION on maximum speeds is enforced on the west-bound express while travelling on the Salisbury-Exeter section of the Southern Railway, the route being well aligned. This illustration shows the “Atlantic Coast Express” passing at speed through Seaton Junction (Devon), 148 miles from Waterloo and twenty-three and three-quarter miles from Exeter.

It has only been during the periods of through working that engines of the “Lord Nelson” type, attached to the Nine Elms shed, have been seen as far west as Exeter. At all other times the principal expresses between Salisbury and Exeter are hauled by the exceptionally capable 4-6-0 engines of the “King Arthur” type, and it is over this route that some of their most remarkable performances have been accomplished.

The Salisbury-Exeter section of the Southern Railway is unique. It is, in effect, a switchback on a gigantic scale, with gradients frequently steepening to 1 in 100, and even to 1 in 80. The worst bank is one of 4½ miles at 1 in 80 preceded by 1½ miles at 1 in 100 - a most formidable task to face the engine of a fast and heavy express. On the other hand, so well aligned is this route that there is no restriction whatever on maximum speeds, save one slight check in the descent of the bank just mentioned, through Seaton Junction. Drivers may, and do, get every ounce of speed out of their engines down these inclines, to obtain all the impetus possible for mounting the subsequent ascents. The timings of 96 and 98 minutes over the 88 miles from Salisbury to Exeter - and the morning “newspaper” makes an even more exciting journey in 93 minutes - thus require an average speed of from 54 to nearly 57 miles an hour from start to stop. They are probably the fastest in the world over gradients of such severity. The interest to the railway enthusiast is that such sharp timings as these will, of necessity, produce a whole crop of eighty-miles-per-hour maxima, often up to four or five all told - at well-separated points - on the one run.

The Approach to Devonshire

Out of Salisbury, left at 12.31 pm, the train has a long and gradual climb to Semley (17½ miles), the nearest station to Shaftesbury, finishing with two miles at 1 in 145. Suddenly a thrilling acceleration is felt; in the next four miles, to Gillingham (21¾ miles), speed probably rises to eighty miles an hour. Up the line climbs, to Buckhorn Weston Tunnel, and again it drops at 1 in 100 for two miles, to Abbey Ford. Templecombe Bank lies ahead - 1½ miles at 1 in 160 and a mile at 1 in 80 - and brings speed down to the “fifties”, or less, followed by another “hurricane” speed-up on the 1 in 80 descent to Sherborne (34½ miles), where a second “eighty” maximum speed will probably be attained.

To Yeovil Junction (39¼ miles) there are now 5½ miles of undulations, followed by Sutton Bingham Bank (3½ miles at 1 in 200 to 140). Then, after a moderate stretch of downhill, comes the more severe climb of Crewkerne Bank, which for 2¾ miles is at 1 in 80, and may reduce the speed of the train to but little above thirty miles an hour, when the short summit tunnel has been threaded.

The next thirteen miles, from Hewish onwards (50½ miles), provide the finest racing ground of the whole down journey. This stretch is uninterruptedly downhill, on what are, for the most part, moderate gradients, and easy steaming will produce a speed that for the major part of the descent is well above seventy miles an hour, and has probably exceeded eighty by the time Axminster (61 miles) is passed. Just beyond Axminster, at the foot of the bank, the main line is at the nearest point that it reaches to the south coast, near Lyme Regis, in Dorset.

The track now turns inland again, and the engine is faced with the arduous climb to which previous reference has been made. This is eight miles long, and for 4½ miles it is graded at 1 in 80. The impetus of the preceding descent has been expended long before the summit is reached, and the last mile or so to the summit tunnel will be breasted with the speed somewhere between twenty and twenty-five miles an hour. At last the tunnel is reached, and the train is soon dashing down from the farther side through Honiton (71¼ miles).

At Sidmouth Junction (75¾ miles) a stop is made at 1.58 pm to detach the Sidmouth and Exmouth coaches. And only a brief twelve-miles run now remains to Exeter. But it includes another steep descent, through Whimple to Broad Clyst (83¼ miles), down which the final eighty-miles-an-hour maximum may be expected. The writer's first acquaintance with this section was made on the footplate of a small Drummond 4-4-0, which beat all pervious maxima on the journey by touching 87 miles an hour at this point. And now, hurrying past the remodelled Exmouth Junction engine-sheds, with their modern reinforced concrete equipment, the “King Arthur” at the head of the train pulls into Exeter Central (formerly, Queen Street) at 2.17 pm. Here another example of Southern Railway enterprise is seen, as the station has in recent years been rebuilt in most up-to-date fashion, and is now a credit to the city of Exeter. We are here 171¾ miles from London, and have reached the farthest limit to which the “King Arthurs” are permitted to travel, as certain structures more to the west are not able to carry their weight. So the lines west of Exeter are now the happy hunting-ground of the “Moguls”, whose 6-ft driving wheels are also better suited to the extremely steep gradients of the remainder of the route than the 6 ft 7 in driving wheels of the express engines. The restaurant cars are here detached from the rear of the train, which itself is split into two parts, that for Ilfracombe and Torrington leaving first, as 2.21 pm, followed by the Padstow, Bude, and Plymouth portion at 2.28 pm.

Meeting the Great Western

Out of the Central Station to the west, the line drops in most precipitate fashion; the half-mile at 1 in 37, indeed, is the steepest gradient on the whole route between London and Plymouth. Fortunately the descent is but short; it leads down into the Great Western Railway St. David’s Station, at which also all Southern trains stop. Every Southern Railway train bound for London requires assistance from St. David’s up to Exeter Central, which is generally given by 0-6-0 tank locomotives used as bankers. Two are used together to bank the heavier trains.

A peculiarly interesting feature of St. David’s Station is that it faces roughly north and south. The Great Western expresses from Paddington enter from the north end, and the Southern expresses from Waterloo from the south end, so that they pass one another travelling in opposite directions. But, as if this were not enough, when the same two railways reach the North Road Station at Plymouth, the west-bound Great Western express arrives in orthodox fashion from the east end, whereas the Southern Railway train from London has now completely boxed the compass, and appears in the station from the west end. It would thus be possible for the same two trains, travelling from London to Plymouth, to meet each other twice in succession, and in both instances running opposite ways.

But it would not be likely for such a double meeting to take place, as the Great Western is now the faster route, both between London and Exeter, and between Exeter and Plymouth. In the early years of the present century the London and South Western Railway, with only 171¾ miles to go from London to Exeter, as compared with the Great Western 194 miles via Bristol, put up a fine fight, and for some time equalled if it did not beat the quickest Great Western schedules to Exeter and beyond. But the completion of the Westbury route in 1906 cut twenty miles from the journey of the Great Western expresses, and the Great Western gradients are, on the whole, so much the easier of the two that the Southern Railway is no longer able to equal the Great Western times, from London to Plymouth in particular.

PADSTOW STATION, in North Cornwall, 260 miles from Waterloo, is the most westerly destination of a through coach of the “Atlantic Coast Express”. The Padstow section of the express parts company from the Bude section at Halwill Junction (Devon), forty-nine and three-quarter miles from Padstow.

As previously mentioned, the Ilfracombe and Torrington sections of the “Atlantic Coast Express” are the first to leave Exeter. From St. David's Station a stretch of the Great Western main line, 1½ miles long, is followed in the direction of London, as far as Cowley Bridge Junction, where the Southern Railway track bends westwards. The fertile valley of the Taw carries the train gently down to Barnstaple, 38¾ miles from Exeter Central. At Barnstaple the line divides again, the Torrington coach being left behind to make its journey round through Bideford to its destination. The Ilfracombe coaches, after passing Braunton, seven miles beyond Barnstaple, have some mountainous gradients to tackle: for 3½ miles from Heddon Mill the climb is at 1 in 40, up to Mortehoe, six miles farther on. But even this is beaten by the final descent to Ilfracombe, 54¾ miles from Exeter Central. For 2½ miles the gradient is at 1 in 36 - a formidable obstacle for London-bound trains as they leave Ilfracombe.

The most “Atlantic” portion of the “Atlantic Coast Express” - the section destined for Padstow, Bude, and Plymouth - runs from Exeter over the same metals as the Ilfracombe train as far as Yeoford Junction, 11¼ miles from Exeter Central. What this route lacks in steepness of gradient, as compared with the Barnstaple-Ilfracombe line, it certainly makes up in altitude. By long stretches rising on a 1 in 77 gradient the Plymouth main line climbs to no less than 950 ft above the sea, on the northern slopes of Dartmoor, just beyond Meldon Junction and 201 miles from Waterloo. Between Exeter and Plymouth no fewer than twenty-seven miles of the route are as steep as 1 in 75 or 1 in 80. Near Meldon Junction, crossing a deep valley amid these breezy uplands, is the spidery form of Meldon Viaduct, the highest structure on the Southern system.

Before reaching Meldon Junction the train calls, at 3.14 pm, at the moorland town of Okehampton (26 miles from Exeter Central), where the Padstow and Bude coaches part company with the one destined for Plymouth. The former have a long single-line journey to the westward. The Bude and Padstow lines diverge at Halwill Junction, 12½ miles from Okehampton; Bude is 31 miles from Okehampton. Padstow, 62¼ miles from Okehampton, and 260 miles from Waterloo, is the most westerly point reached by the Southern Railway. From Halwill to Wadebridge, the last station before Padstow, there are forty-four miles of line without a single junction or branch.

It is curious to reflect that the original 11 am from Waterloo was for many years an express to Plymouth, with a through portion for Ilfracombe attached, most of the other destinations of the present “Atlantic Coast Express” being then reached only by connexions into which the passenger had to change. Now the Plymouth express has shrunk to one coach, which, attached to two or three others to complete the train, makes its lonely way across the moors, dropping down into Tavistock, and so to the valley of the Tamar. The Ilfracombe portion, on the other hand, has become the main train.

Running underneath Brunel’s masterpiece - the Saltash Bridge - we shortly reach Devonport, and at 4.15 pm are in North Road Station at Plymouth. Stopping also at Mutley, we finally reach Friary Terminus of the Southern Railway, 234 miles from London, at 4.26 pm. But it is not till 5.37 pm, when the Padstow coach reaches its destination, that the last component of the "Atlantic Coast Express" comes finally to rest on the Atlantic shore.

Si milarly it is Padstow which takes leave of the first section of the up “Atlantic Coast Express”, at 8.35 am. The Ilfracombe section starts art 10.30 am, and the whole train, leaving Sidmouth Junction at 12.55, reappears at Waterloo at 3.55 in the afternoon.

milarly it is Padstow which takes leave of the first section of the up “Atlantic Coast Express”, at 8.35 am. The Ilfracombe section starts art 10.30 am, and the whole train, leaving Sidmouth Junction at 12.55, reappears at Waterloo at 3.55 in the afternoon.

AT SPEED in Weybridge Cutting, near Weybridge Station, nineteen and a quarter miles from Waterloo. The “ACE” on this section will normally be running at over sixty-five miles an hour. The first stop of the express is at Salisbury, eighty-three and three-quarter miles from London, reached in eighty-seven minutes. This is good running, as the beginning of the journey is through a congested suburban area, and is “against the collar” for fifty-one miles.

You can read more on “The Golden Arrow”, “The Story of the Southern” and of an earlier trip (in 1927) on “The Atlantic Coast Express” on this website.

milarly it is Padstow which takes leave of the first section of the up “Atlantic Coast Express”, at 8.35 am. The Ilfracombe section starts art 10.30 am, and the whole train, leaving Sidmouth Junction at 12.55, reappears at Waterloo at 3.55 in the afternoon.

milarly it is Padstow which takes leave of the first section of the up “Atlantic Coast Express”, at 8.35 am. The Ilfracombe section starts art 10.30 am, and the whole train, leaving Sidmouth Junction at 12.55, reappears at Waterloo at 3.55 in the afternoon.