RAILWAYS OF BRITAIN - 48

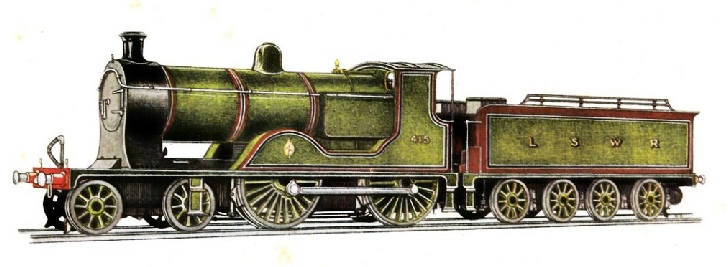

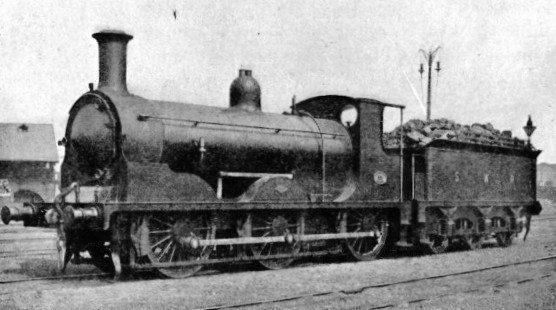

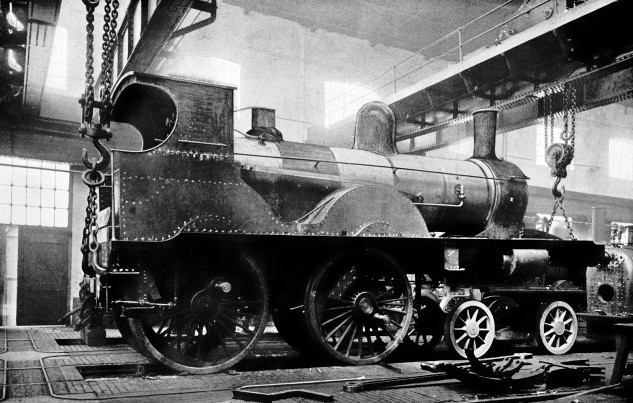

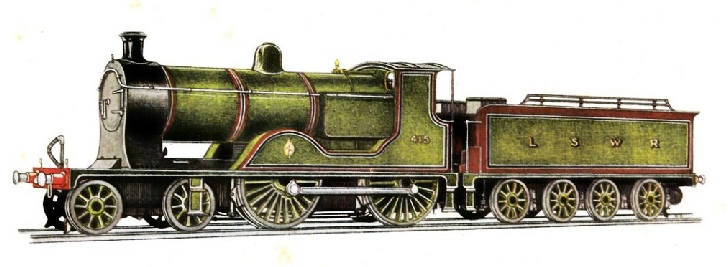

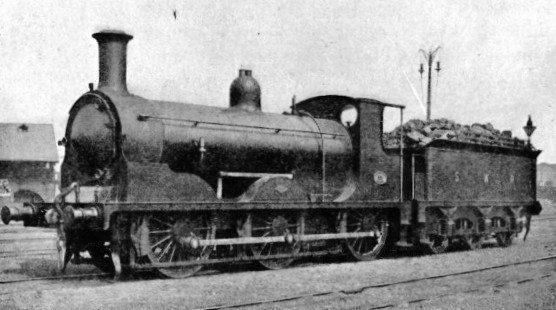

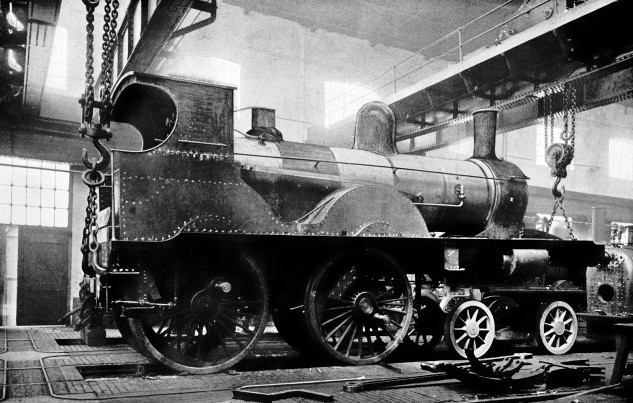

LONDON & SOUTH WESTERN RAILWAY EXPRESS PASSENGER LOCOMOTIVE, No. 415

DESIGNED BY Mr. D. DRUMMOND, M.INST,C.E.

The South Western - for so it is always called notwithstanding the other South Western over the Border - has been associated with Southampton from the beginning. The insecurity of the Channel, even after Trafalgar, had clearly shown the advisability of an inland route to London to avoid a sea passage at the mercy of an enemy’s cruisers and privateers; and it is not to be wondered at that in the days of canals a canal was projected. But fortunately little was done. The London end, the Grand Surrey, stopped at Camberwell, and when another start was about to be made railways had begun to pay, and the canal gave place to the London & Southampton Railway.

It was the shipowners of Southampton who put the company afloat. Seeing in 1830 what the Liverpool & Manchester was likely to do for the shipping of Liverpool, they talked matters over together, and in April 1831 there appeared the prospectus of - notice the significance of the title - the Southampton, London, and Branch Railway and Dock Company. As enough money could not be raised for this, a meeting was held in London at which the dock part of the scheme was abandoned, to become a separate enterprise, thereby reducing the capital by half a million, and in the session of 1832 a Bill was introduced into Parliament for the construction of the London & Southampton Railway, which was thrown out. Next year it met with a similar fate, but in 1834 the promoters were more fortunate, and at a cost of £31,000 for legal expenses the Act was obtained, the capital being one million with a third as much in loans - and it was nearly all spent in two years.

Had the route been direct much money would have been saved, but it went almost due west from Woking to Basingstoke, with the intention of throwing off a branch to Bristol, and this aroused the hostility of the Great Western people, who did their best to prove the embankments so huge and the gradients so steep that the line could never be made or worked. The engineer was Francis Giles, who had surveyed for Rennie’s Portsmouth canal, and who when the Liverpool & Manchester Bill was before Parliament gave evidence that “No engineer in his senses would go through Chat Moss if he wanted to make a railway from Liverpool to Manchester”. When the Southampton Bill was before the House the Great Western called George Stephenson on their side, who promptly had his revenge with “No engineer in his senses would go through Basingstoke if he wanted to make a railway from London to Southampton!” But as Giles had been mistaken, so was “Old George”.

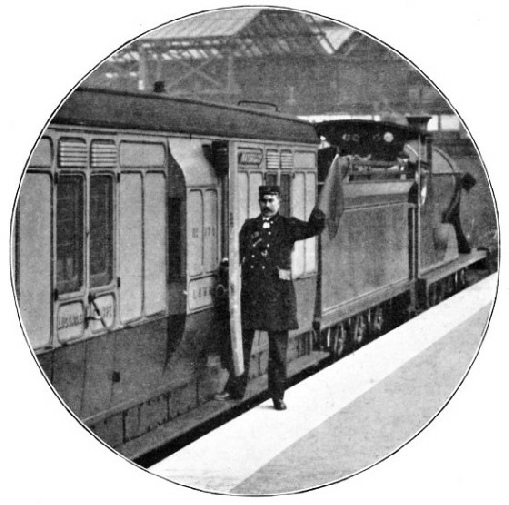

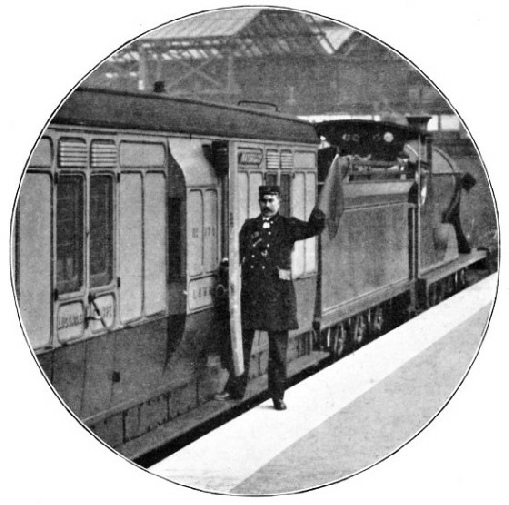

THE MAIN LINE DEPARTURE PLATFORMS AT WATERLOO

Giles had to get through the Hampshire ridge, and he ran the line at so high a level to avoid as many long tunnels as he could. The earthworks were tremendous for those days, sixteen million cubic yards of them, and there were difficulties of many kinds, not the least being that the work had been let out to small contractors, who obtained payments on account and cleared off as soon as the contract ceased to pay them. There was practically no progress, and matters came to a crisis. Many of the shareholders were Lancashire men, - “the Liverpool party” of the South Western, in fact, - and these, after bringing about the resignation of Giles, put Joseph Locke of the Grand Junction in his place, who called in his friend Thomas Brassey, and in their capable hands the construction went steadily on. This was Brassey’s coming to London. He was then thirty-one, and the contract for the portion between Basingstoke and Winchester, and other parts of the line, was his first big job. With it he commenced a career which was to take him railway-making over a large part of Europe, India, and Canada.

The terminus was at Nine Elms, the present goods yard; so placed by the bank of the river as to secure a share of the barge-borne trade of the port of London. The first station, called Wandsworth, was really in Battersea, being - according to the map at South Kensington - on the north side of the road where Battersea Rise ends at what is now the Freemason bridge. The Brighton line, running along the site, bears away just at the spot, and on the other side of the road that company in 1856 built a passenger station, now used for goods only, which, to distinguish it from the old one, was called New Wandsworth and gave the name to the district. At Earlsfield, skirting the east side of Garratt Lane, just before crossing the Wandle, the line went over the old Surrey Iron Railway to Croydon; Wimbledon was the second station from Nine Elms; then came Kingston - at Surbiton - placed so far away from the town that Surbiton was known facetiously for years as Kingston-upon-Railway, until, in fact, the present Kingston Station was opened on the loop line. Next came Ditton Marsh - now Esher - then Walton, then Weybridge, then Woking Common, the present Woking, to which the line was opened on the 12th of May 1838.

Meanwhile work was in progress on the way to Shapley Heath, now Winchfield, and at the other end between Southampton and Winchester. Beyond Woking the task was heavy owing to the cuttings and embankments, and beyond Farnborough there was Fleet Pond to be crossed along the sandbank faced with turf, thatched with hazels, pinned with willows, and edged with chalk. The line still rising went on to its summit level at Litchfield, 392 ft, and then ran down through the tunnels and under the canal to Basingstoke. In June 1839 trains began to run from London to Basingstoke and from Southampton to Winchester, a coach ride filling up the gap until May 1840, when the first train ran through to Southampton. The works had cost over two millions, more than double Giles’s estimate, much of it raised by issuing the £50 shares at half price.

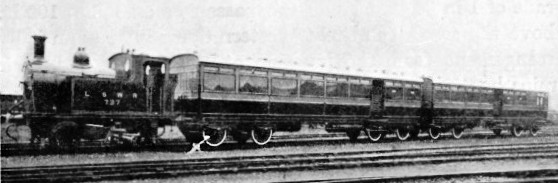

THE 10.45 A.M. DOWN PLYMOUTH EXPRESS, NEAR WILTON, IN CHARGE OF No. 457

The first branch was to Gosport from Bishopstoke, now Eastleigh. This was easily arranged. Portsmouth wanted a railway, but would have nothing to do with anything bearing the detested name of the rival port. At the same time it was evident that a branch from the existing line would give much cheaper access to London than an independent one all the way that would cost a fortune in legal expenses to get sanctioned by Parliament. Could nothing be done? “Is it our name only you object to?” asked the Southampton directors. “That is all”. “Well, then, that can be settled at once. Instead of the London & Southampton we will call our line the London & South Western”. And the Portsmouth people were delighted, the Gosport branch was made, and the railway took the name we know it by.

It might be called the recreation line, for what with its nine racecourses, and the Thames boating and reviews and sundries, it makes more out of sport and pleasure than any other. And it began early. The first chairman was Sir John Easthope, a successful stockbroker, proprietor of The Morning Chronicle, etc, whose breezy, interfering ways were quite a feature of all the small stations on the road to Weybridge, where he lived. As he added racing to his other interests there was nothing surprising in the new railway announcing that on the Derby Day, eighteen days after the opening, eight trains would run from Nine Elms to Kingston - Surbiton - for the convenience of the public, who could walk the rest of the way to Epsom. The idea does not seem attractive to us now, but things have changed. So pleased were the people at the opportunity that they swarmed down to Nine Elms early in the morning and formed a crowd of 5000, who, not being prepared for, carried the station doors off their hinges, took possession of the platform - which was 15-in. high - filled all the carriages in sight, and after doing much damage had to be cleared off by the police. If this was not an indication of the need of a branch to Epsom, Sir John had never heard of another; and so the Epsom branch was the first to be proposed. But unfortunately the forefathers of the Brighton, the London & Croydon, had also their eyes on Epsom, to proceed there atmospherically, and they brought in an opposition Bill which met with Parliament’s approval while the other did not. Their atmospheric road remained in the air, and for some time the Derby and Oaks patrons, more amply provided for, went to the Downs and back by way of Surbiton.

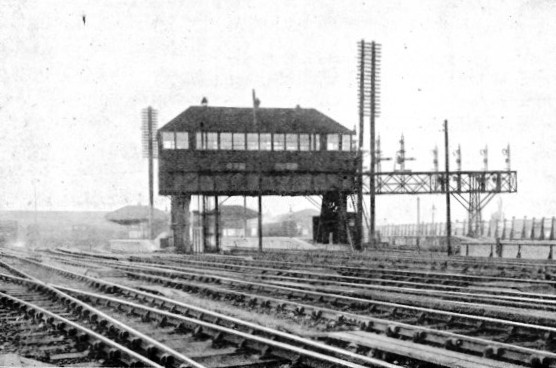

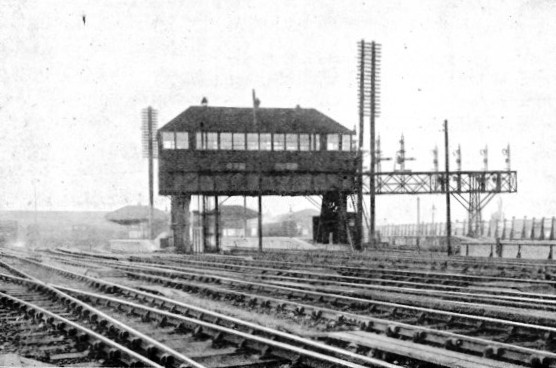

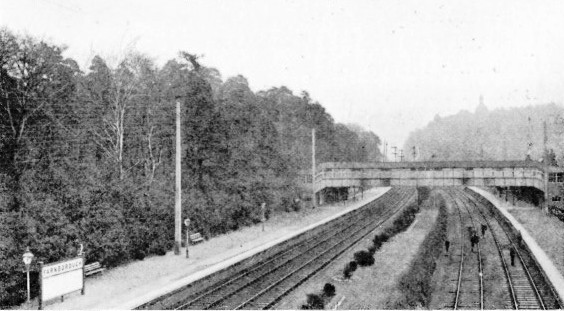

BASINGSTOKE — THE JUNCTION OF THE TWO MAIN ROUTES

Thus the Gosport branch was the first to be opened, the next being that to Guildford, bought from another company who were going to lay it with wooden rails. The next was that to Richmond, afterwards extended to Windsor, which was reached in December 1849. This branch went off just before the first cutting, now known as Clapham Cutting; and in making this cutting, springs were dug into which flooded the excavation, and, to work the pumps for clearing it, the engineer built the windmill which still stands, without its arms, overlooking Wandsworth Common.

A new station was built near Falcon Lane, taking the place of the so-called Wandsworth, and to be called Battersea, or rather Battersea Junction. But the name was changed to Clapham Junction; why is a mystery, unless we accept the usual explanation that it sounded more important, for it is very much in Battersea and over a mile from Clapham, to which a branch was never proposed. On this Richmond branch, opened in 1846, the first station was the Wandsworth, now known as Wandsworth Town; a little farther on, close to the Wandle, the line crossed the Surrey Iron Railway to Croydon, as the main line had crossed it at Earlsfield, and as the South Western bought it, just as the Brighton bought the extension from Croydon to Merstham, that old railway ceased to exist on the 31st of August of that year. The next branch was to Salisbury from Eastleigh through Romsey, and the next that to Hungerford Bridge.

The last was the most costly and best of all, though it was only two and a quarter miles in length and the outlay nearly two millions, the station being no other than Waterloo, so named from its main entrance in the Waterloo Road. The well-known station was not intended to be a terminus, for the line was going farther east along the present route of the South Eastern & Chatham, and much of the property had been secured, such insignificant items as Barclay & Perkins’s brewery and Southwark Bridge being about to be taken over by the company, when the financial crisis made them pull up where they have remained.

THE NEW SOUTH STATION AT WATERLOO

Waterloo Station now covers twenty-two acres. Within it are nineteen roads, that is to say that when full it holds nineteen trains abreast, and the bridge over the Westminster Bridge Road by which it is approached carries eleven roads. Over 2500 trains, engines, etc, are dealt with every day, and as many as 12,000 passengers are despatched from it during the busiest half-hour of each working day of the week, for the South Western suburban traffic extends far beyond the range of competing trams.

Trains no longer go from London to Salisbury by way of Eastleigh, but direct from Basingstoke, and the main line is fairly straight all the way to Exeter. North of it the spurs are to Windsor, Wokingham, and Bulford; south of it the branches lead down, with many intercrossings, to Portsmouth, Southampton, Bournemouth, and Dorchester. Beyond Salisbury the southerly branches serve the coast again between Lyme Regis and Exmouth, and from Exeter goes the great curve round the beautiful country of Dartmoor to Plymouth, throwing off the picturesque roads to Barnstaple, Ilfracombe, Torrington, Bude, and Padstow. Altogether just over 1000 miles of track, every mile carrying on the average 66,000 passengers a year.

The great feature of the system is the way in which the branches loop up with other branches, or end in communication with other systems so as to provide alternative routes and through routes for passengers and merchandise. There are less than a couple of dozen loose ends that do not form a junction with some other line; and of these more than half have their terminus on the coast; three of them, Hampton Court, Shepperton, and Windsor, end on the banks of the Thames; and two, Bisley and Bulford, are for military purposes.

The South Western is our most important military line. It skirts the Channel, and has more military stations on it than any other. It connects the three great naval stations, Portsmouth, Portland, and Plymouth, with the two great camps, and serves as many garrison towns as it does cathedral cities. The road it jointly owns with the Brighton into Portsmouth is the only one in the country that passes through a rampart. And, owing to the concentration of the troopships at Southampton, it carries every British soldier that goes or returns on foreign service.

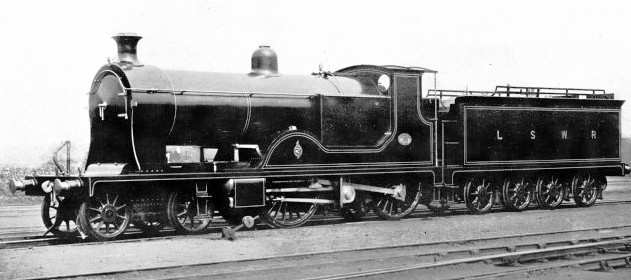

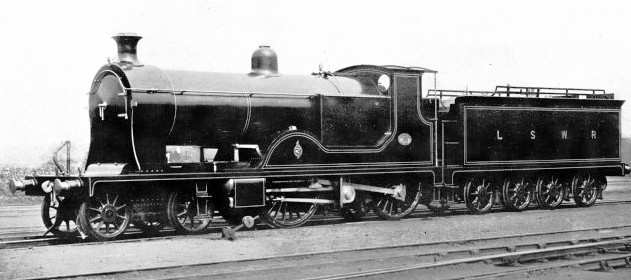

FOUR CYLINDER EXPRESS PASSENGER LOCOMOTIVE, No. 720

On the Channel the seaside towns it serves are Southsea and those of the Isle of Wight; Lee, Lymington, and Bournemouth; Poole, Swanage, and Weymouth; Lyme Regis, Seaton, and Sidmouth; Budleigh Salterton and Exmouth. North Cornwall it claims for its own. From Bude, the nearest Atlantic port to London, it runs the coach rides northward to Clovelly and southwards to Boscastle that excel all others. From Clovelly downwards is the rockiest, healthiest coast in England. Along it is the real blue water, for the nearest over-the-way to the west is America. Beautiful in every mood, splendid in the sunshine, terrible in the storm, let those who would know what an Atlantic sea is like venture out in a gale on to the cliffs at Morwenstow or Bude, or that pirate’s wild harbour, Boscastle, or even windier Tintagel, and they will learn what they cannot learn on the coasts of the Channel and the North Sea.

The history of the line in the west is that of a sixty years’ war with the Great Western. As the champion of the standard gauge in the south, the broad-gauge people naturally endeavoured to stop its advance, and that all the more strongly from its being an invader. But battles over private Bills have lost so much of the little interest they had for those not engaged in them that we need not dwell on them here.

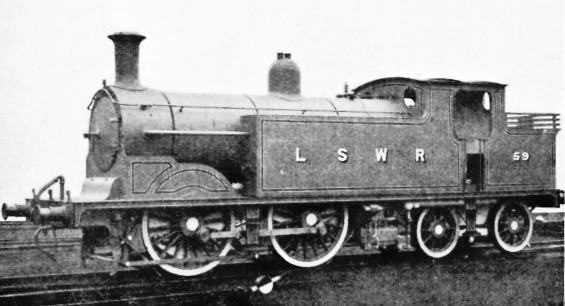

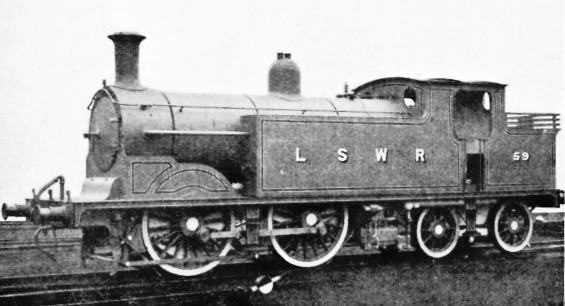

TANK ENGINE No. 59 - A TYPE USED FOR THE HEAVY SUBURBAN TRAFFIC

What the South Western intended to do was clearly shown in 1846, when it took shares in the Sutton harbour at Plymouth, which was not reached until forty-two years afterwards, as also in 1845 when it bought the Bodmin & Wadebridge. This little, single, narrow-gauge line was opened in 1834 at a cost of £35,000 for the purpose of carrying sand from the Camel River, which the farmers of Bodmin were then using in large quantities as a top-dressing for their pastures. It was worked by two engines, the Camel and the Elephant, made by Tregellas Price of Neath. On it ran a passenger train, up one day and down the next, up being from Wadebridge on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. It was laid as railroads were laid then, with light rails on tiny chairs fastened down to granite blocks by a couple of tenpenny nails, and was perhaps more lightly built than usual as it was the only sand line ever made; and the sands of its time began to run out from its commencement. Eleven years after it was opened, being then in a bad way, the Cornwall Railway, that is the Great Western under another name, offered to buy it, provided the Cornwall Railway Act was obtained, and the Cornwall & Devon Central, the competing company, did likewise whether they got their Act or not. The Wadebridge people accepted the definite offer - £33,096, 9s. 8d. - and the Cornwall & Devon Central, which never had a line but were financed from Nine Elms, passed on the bargain to the South Western, who thus obtained an outpost in the west, two hundred miles away, which it took fifty years to reach, and now works with a steam rail-motor car.

The most noteworthy of the links towards it was the Salisbury & Yeovil, which when the first sod was cut in April 1856 had a bank balance of £4. 2s. 4d. With many a struggle, frequently with no idea where the next £500 was coming from, it paid for the work of almost all kinds with shares at a greater and greater discount, until the cost, half a million, was somehow met; and then it was opened, worked by the South Western for half its gross receipts. When the Yeovil & Exeter was opened this 50 per cent, became 42½ for twenty-one years, plus a quarter of the traffic receipts to the South Western stations, an onerous undertaking resulting in the line being worked at such a loss to the South Western, and such a profit to the Salisbury & Yeovil, that in 1878 the South Western bought the property. And the price was £260 for each £100, so that its shareholders, whose early prospects were so gloomy, secured 13 per cent, in the few cases in which they had bought at par, and higher rates in proportion to the lower prices at which the shares had been distributed to them.

The South Western owes a good deal to “running powers”. It crosses the Great Western at Exeter on nearly a mile and a half of the competing line. It gets into Plymouth on over two and a half miles of the Great Western, into Weymouth on nearly seven miles of the Great Western, into Reading on nearly seven miles of the South Eastern & Chatham, and into Portsmouth, by the direct route, on nearly four miles of the Brighton (from Havant to Port Creek). These are all triumphs of its diplomacy, but perhaps the smartest thing it did was the purchase of the line to Midhurst, by which it stopped the advance of the Brighton to Southampton.

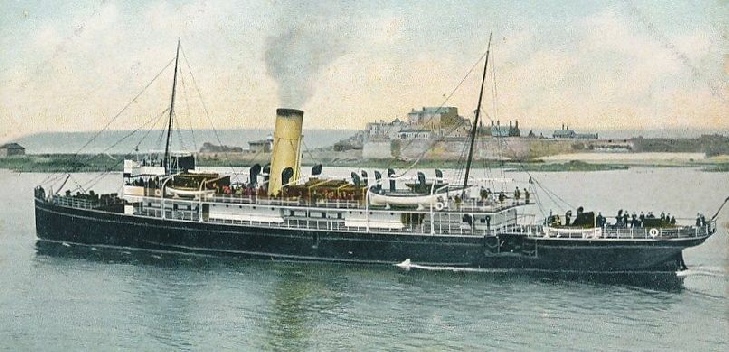

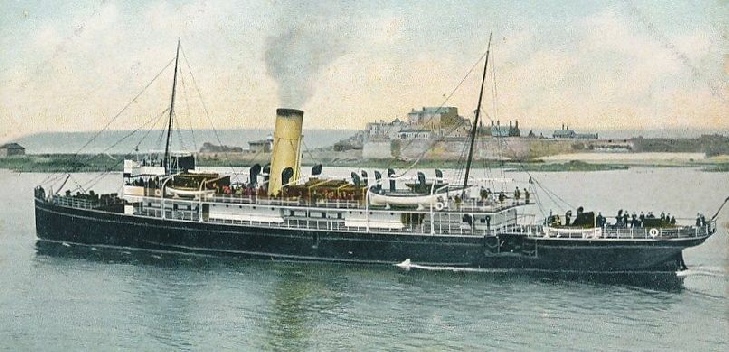

DEPARTURE OF AN AMERICAN LINER FROM SOUTHAMPTON DOCKS

Southampton, the pleasantest of our larger ports, is the real heart of the South Western and the main cause of its prosperity, for it means goods, and no railway company can thrive without goods. When the London & Southampton was launched the dock scheme was undertaken by another company, who began by building what is known as the Outer Dock. Before that dock was opened the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, and the Peninsular & Oriental, had begun business, and made Southampton their headquarters, and in 1847 steamers from Bremen, owned in New York, began to call in, these being the predecessors of the North German Lloyd, a company formed at Bremen in 1856, which has all along made Southampton its English port of call. In 1845 the South Western Steam Navigation Company purchased the Channel Island boats, which had up to then been running from Weymouth, and transferred them to Southampton, adding a service to Havre. In 1862 the South Western took over this company, thereby increasing its interest in the docks, and the successors of these old paddle boats continue both services and are among the best that cross the Channel. It was the trade with the Channel Islands, still worked from the Outer Dock, that led to the subsequent developments, though the business done in the carriage of passengers and merchandise brought by the ocean-going steamers became increasingly important.

For instance, in 1853 there started the Union Steam Collier Company, with a view to supplying coal to the vessels frequenting the port; but during the Crimean War the P. & O. fleet were taken up as transports, and the Union boats were put on to trade with the Levant in their place until they were in turn secured for transport purposes. When the war was over employment had to be found for these boats, which, as the Union Steamship Company, endeavoured to open a trade with South America, and in 1857 left the South American trade for the South African, owing to the company obtaining the mail contract to the Cape. The same year the Bremen steamers having found it pay them to call at Southampton, the opposition line from Hamburg, the Hamburg-American, followed their example, greatly to the advantage of the dock company, whose only difficulty was how to find capital for improving the accommodation. In 1875, as nothing was done, the P. & O. left for the Thames, causing a drop of 50,000 in the port’s tonnage, which a sudden spurt of trade more than made good in the next year’s return. Prosperity continuing, and matters going on in the old way, negotiations were begun in 1883 for the town authorities to take over the docks and make the inevitable enlargement; and as these failed the dock people applied to the railway company for help.

The man was ready for the hour. In 1885 Sir Charles Scotter, then Goods Manager of the Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire, had been appointed General Manager of the London & South Western. He had begun his career with the M. S. & L. at Hull, and he had risen to have the management of Grimsby; and no man in the country knew more about docks, and what could be done with them when they were owned by a raihvay company. Little wonder, then, that in 1886 the South Western subscribed a quarter of a million to the dock company’s capital account for the extensions to be put in hand, and that six years afterwards the railway company should become the sole owners of the property with a view to the greater developments that are still going on.

A SMART AND USEFUL LOCOMOTIVE, No. 736

Southampton is fortunate in its position in the middle of the south coast, under eighty miles from the capital, and about half as much again from the Welsh coalfield and the manufacturing towns of the Midlands. Across the mouth of the estuary lies the Isle of Wight, acting as a huge breakwater, favouring it, like a few other places in the world, with a double tide. As the tide runs up Channel it sends off a branch at the Needles into the Solent, and proceeding along the south of the island it sends another branch into Spithead about a couple of hours later; the main tide, in fact, which reaches Southampton Water from the east before the one from the west has had time to get out. Thus there are four tides a day, and as there is water enough for all ships at all times, and the anchorage is excellent and well sheltered, the port requires not basins but graving-docks, and quays and jetties along its river fronts.

The business largely lies along the outer wall, and the quayage is great, the docks being traversed by over thirty miles of railway; and the outfit of steam, hydraulic, and electric appliances for hauling and lifting is unusually large, for three-fourths of the light imports are sent to London, being perishable articles calling for instant despatch. The heavier goods are more widely distributed, and for those that have to stay for a while there are huge warehouses, bonded and free, for all kinds of merchandise, and grain stores with elevators and travellers that deal with 200 tons an hour.

The oldest trade of the port is that in wine, and the amount is now enormous; the newest trade is that in chilled provisions, and the cold storage accommodation of 2,000,000 cubic feet is the largest in the country. This cold storage business is a most interesting feature, for the meat is not loaded into covered wagons, but direct into road vans with their shafts taken off, and their wheels lashed to iron rails on double carriage trucks. A train of these carts, each taking thirty-four quarters of beef, is loaded alongside the stores and run straight up to Nine Elms where the horses are awaiting them, and the load, after being handled only once, is delivered at Smithfield within four hours of leaving the cold room at Southampton.

A GUARD OF THE SOUTH WESTERN

What with the many liners now using the port, and the troopers and smaller fry, there is always plenty of shipping about, and many steamers mean much coal; and Southampton handles coal in a way of its own. The only storage is in lighters, so that it is ready to be towed to the ships as soon as ordered. Along the river fronts of the coal barge docks runs a narrow jetty, where the cranes lift the coal out of the colliers a couple of tons at a time and swing it across into the lighters waiting on the other side in such numbers that 14,000 tons of coal may be afloat at once, there being lighterage capacity for no less than 20,000.

Another of the Southampton sights is the Prince of Wales graving-dock, 750 ft. long and 112 ft. wide, a vast cavity in which the men, apparently dwarfed to half their size, work in the dry owing to the constructor having thoughtfully made it turtle-backed, so as to drain the water off at the sides instead of in the middle. Big as it is it can be filled in an hour and a half and emptied in two hours and a half by means of centrifugal pumps a yard in diameter. Farther on is the Trafalgar graving-dock, which is larger, it being 875 ft. in length; and each of its gates weighs 250 tons! And even this is to be enlarged. In short, the dock business is being worked for all it is worth, and it will not be the fault of the South Western if its growth is in any way checked.

The Midhurst branch goes off at Petersfield on the Portsmouth Direct, which has an interesting history. It was made by Brassey for an independent company, a line of heavy gradients with its summit at Haslemere, 460 ft. above the Waterloo level, to join up with the South Western at Godalming and with the Brighton at Havant, and was ready for opening in January 1858, but the owners had made no preparations for working it, and had provided no rolling stock, hoping that one of these companies would take it over. The Brighton people would not undertake the task, as it was a competing route to Portsmouth, to which they had been running for eleven years; and the South Western declined, as it would interfere with their agreement with the Brighton. Then the owners obtained parliamentary sanction for a junction with the South Eastern at Shalford, hoping that that company would come to the rescue, but received the same reply, that prior arrangements with the Brighton precluded any such working of an opposition line. One way out of the difficulty seemed to be to continue the Portsmouth Direct to Portsmouth, which led to the proposal of another Portsmouth terminus at Landport. This did not suit either the Brighton or the South Western, and at last the South Western were persuaded to take a perpetual lease of the line at a rental of £18,000 a year and risk a war.

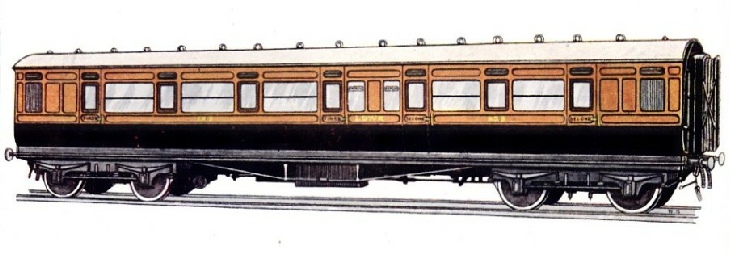

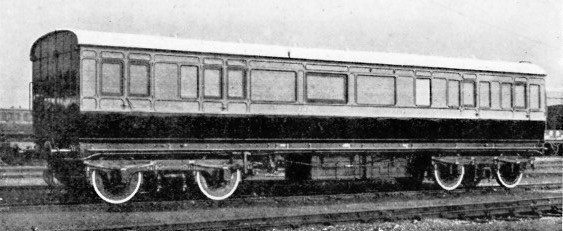

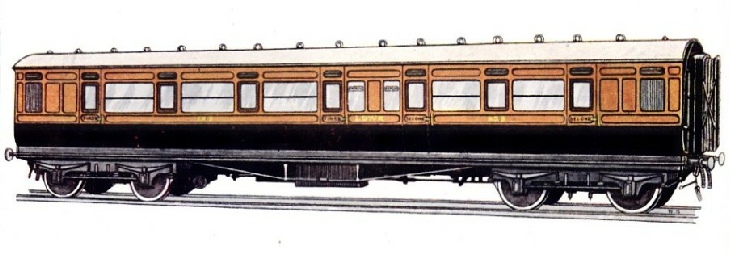

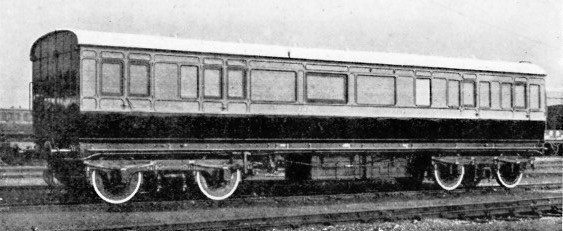

LONDON & SOUTH WESTERN RAILWAY COMPOSITE CORRIDOR CARRIAGE NO. 859

The Brighton at once accepted the challenge. It was on the 1st of January 1859 that the first South Western train attempted to run on to the Brighton metals at Havant. It was to reach there at 10 a.m, but expecting trouble it came at 7 a.m, a train specially manned with 100 platelayers under the command of the secretary of the company, who on his arrival found the rails taken up at the junction and an engine with its wheels chained and padlocked down to the rails at the crossing. A fight began between the rival roughs; the Brighton men were driven back and held at bay, while the South Westerners made good the track, filed through the chains, moved the Brighton engine off and brought their own train on to the metals. But while they were busy in front their opponents were as busy behind, and when the South Westerners advanced they found that rails had been removed farther on, so that progress was impossible. And so the Waterloo men returned to fight the battle with legal weapons that proved so efficient that on the 24th of the month they triumphantly rode into Portsmouth on the metals of the discomfited Brightonians, who forthwith began a war of rates and fares which did nothing beyond causing them a loss of £80,000.

One of the best moves made by the South Western was the leasing of the Somerset & Dorset in conjunction with the Midland. By this Bournemouth obtained the direct route to the north, by which it has profited so much, and the joint companies not only obtained access through Glastonbury to Wells, Burnham, and Bridgwater, but a short communication between each other’s territory. The Somerset & Dorset affords a remarkable instance of development since it ceased to be local and became linked up into a main road. The broad-gauge Somerset Central, from Highbridge on the Bristol & Exeter to Glastonbury, obtained its Act in 1852; four years afterwards the narrow-gauge Dorset Central was incorporated to run from Wimborne to Blandford, obtaining powers in 1857 to continue northwestwards, and, crossing the Salisbury & Yeovil at Templecombe, meet an extension of the Somerset Central through West Pennard and Pylle. The companies then amalgamated, and, as the Somerset & Dorset, built a branch from Evercreech to the Midland at Bath, which was opened in 1874; and next year the Midland and the South Western jointly took over the system on a 999 years’ lease and made it narrow-gauge throughout. From the first the traffic began to improve, and now the line, which is one of the few on which the whole of the trade is dealt with by rolling stock of its own, requires about ninety engines to work it.

In 1865 the Southwestern took over a group of broad-gauge lines giving access to Barnstaple. These originated in the Taw Vale Railway, which after a troubled infancy was built by Brassey during the three years from 1851 as the North Devon Railway and Dock Company. It ran from Crediton to Umberleigh. Brassey leased this line, opened in 1854, as he also did the extension to Bideford from Framlingham Pill, opened in 1855; but in 1863 the South Western secured the North Devon on a lease for a thousand years, and two years after absorbed both it and its extension.

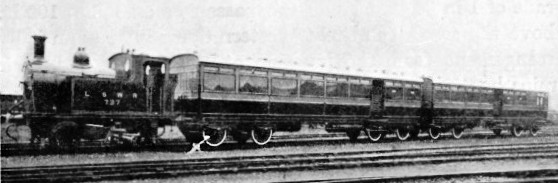

THE VESTIBULE TRAIN WORKING IN THE PLYMOUTH DISTRICT

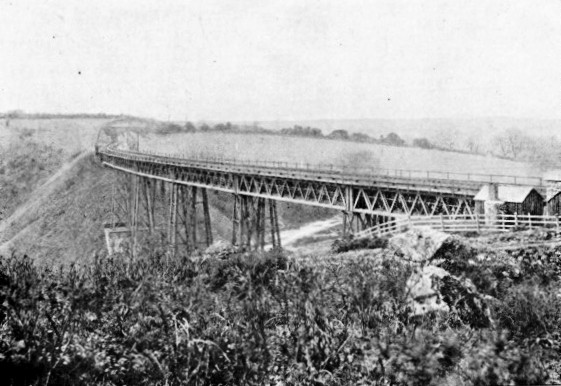

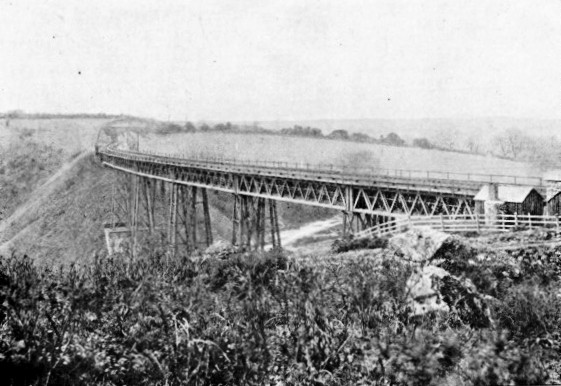

The most difficult working on the Southwestern is that on the Ilfracombe branch, which was made by an independent company after many adventures. It cost only £130,000, and has more heavy gradients and difficult curves than any other stretch of fifteen miles. It begins with a rise, and falls a little only to rise again, and ends in a two-mile downgrade of 1 in 36 that lands the passenger on a hill 100 ft. above the sea. The Great Western Company run on it by arrangement from the junction at Barnstaple, and their trains have to go even more slowly from Morthoe to Ilfracombe than on the harbour branch of the Weymouth & Portland, which is generally reputed to be the slowest bit of work in Britain. Another laborious journey is that round Dartmoor, where greater heights are reached, the summit level of the system, 950 ft, being on that fine section between Okehampton and Tavistock, just after passing over the Meldon viaduct before reaching Bridestowe. This is on the way to the South Western’s other dockyard; for it serves two, Devonport and Portsmouth, just as it serves the two great military camps, Aldershot and Salisbury Plain, and the two ranges, Bisley and Okehampton.

The Meldon viaduct and the Honiton tunnel (1353 yards, the longest on the line) are the two most conspicuous engineering works, if we except the embankments, which do not appeal so much to the traveller. In the making of the line gradients were not worried about overmuch, and were generally taken as they came. Hence the South Western is more undulating than it might have been had the cost of working it been borne more in mind. Some of the inclines are very long, as shown by the distances between the gradient-boards.

These boards, it may be as well to say, which are on the down-side on the South Western and many lines, and on the up-side on others, are required by the Board of Trade to be placed wherever the gradient changes, the arms pointing upwards or downwards according to the slope of the road. The posts for the miles and their halves and quarters are also placed on the line to satisfy the Board of Trade, but owing to amalgamations and short-cuts they have to be used with some discretion as indicating the old road instead of the new, and it is advisable to check the length of the journey they denote by adding up the distances between junction and junction. The South Eastern, for instance, goes by four ways to Ashford, and they cannot be all of the same length, as they appear to be from the posts beyond that station. Other examples will at once occur to the reader, such as the Great Western roads to Weymouth and to Exeter, and the South Western roads to Guildford, Aldershot, Winchester, Kingston, and several other places.

LONDON & SOUTH WESTERN RAILWAY COAT OF ARMS

The South Western is a great line, and has extended far beyond the five towns whose arms figure in its coat of arms, London, Salisbury, Winchester (with the lions and castles), Southampton (with the roses), and Portsmouth. It has always been faster than the others working south of the Thames, indeed in 1847 it was running the fastest train in the world, the Southampton express, which did the 78 miles in 105 minutes including the stop at Basingstoke. Its first locomotive superintendent was John V. Gooch, the brother of the Great Western Gooch, who was just as eager for speed; and this Southampton train was worked by one of his first engines which had 7 ft. wheels, the largest then in use on the standard gauge.

When he left the South Western for the Eastern Counties he was succeeded by James Beattie, who did away with the use of coke as a fuel and in 1855 built the Canute, the first engine to burn coal. In his “smoke-consuming locomotive” he put a combustion chamber, and an enlarged firebox divided transversely by an inclined water-bridge, and containing his great improvement the fire-brick arch. He also perforated the fire-door, and used ashpan dampers and an auxiliary steam-jet to keep the fire going while the engine was at rest. The Canute’s driving wheels were 6 ft. 6-in; she had outside cylinders 15-in. in diameter with a 21-in. stroke; her firebox was 4 ft. 11-in. long, 3 ft. 6-in. wide, 5 ft. 1-in. deep at the back and 4 ft. 1-in. at the front, the area being 107 sq. ft.; her combustion chamber, 4 ft. 2-in. long and 3 ft. 6-in. across, had a flat roof, the area being 37 sq. ft; she had 373 tubes 11-in. in diameter and 6 ft. long, with an area of 625 sq. ft; her fire-grate was 16 sq. ft. in area, and the bricks for consuming the smoke had a surface of 80 sq. ft. She had also a feed-water heating apparatus, and was altogether a remarkable engine. Beattie began, it is worth noting, by using two fires, one of coal, the other of coke for consuming the coal smoke, but he soon found that he could get on just as well with coal alone. The 85-in. Coupleds - 2-4-0, the leading wheels being 48-in. - which worked the South Western expresses for so many years were also designed by Beattie.

Beattie, who was carriage superintendent before he took charge of the engine department, was the first to make railway wheels of wood and iron. Wooden wheels had been tried before, as in the case of the Kilmarnock engine, but the combination was a novelty and it was a success, one set of his wheels running 75,000 miles before being returned to the lathe. This was about six years before the invention of Mansell’s wheel, now generally used for passenger carriages.

GOODS ENGINE No. 691 (WITH CONICAL FRONT)

The Mansell wheel is built up of sixteen segments 3½-in. thick, fastened to the steel boss by bolts passing through the steel disk. The steel tyre is shrunk on to the wood body, which has the grain arranged radially, and the axle is driven into the steel boss at a pressure of sixty tons, giving such a fit that no key is needed. The wheel is free from noise, fans up no dust, and its tyre does not fall off when it fractures; and it is easily balanced.

That the wheels of the engine are balanced everybody knows, but it is not everybody who is aware that the wheels of the carriage are treated in a similar way, or that an unbalanced wheel has a tendency to revolve about its centre of gravity instead of the centre of its axle, and soon develops flat sections on its tread. The balancing of a wheel is not difficult. The pair of wheels on their axle are placed on bearings mounted on leaf springs, and spun round by a pulley for three minutes beneath two markers of chalk fixed so as to just touch the top of the tyres, and by the appearance of the chalk line they take the character of their running can be seen. If they do not run true a small plate of iron of the necessary weight is screwed on to their inside face, and this is altered after trial until the wheel is as it should be. Everything is done to build the wheel so that it requires no balancing, even the segments are weighed separately before being fitted together, but as a rule about 10 per cent, have to carry for life a balance weight of a pound or so.

Another invention of Beattie’s was his buffing apparatus, which had elliptical springs of steel separated by layers of flannel placed between a series of blocks working in the under-frame of the carriage, and thereby protected from the weather. Several more small ingenuities were his, and he certainly ought not to be allowed to drop out of remembrance as he seems to have very nearly done. His passenger engines had their steam domes on the top of the fireboxes. The eight designed by his son and successor, W. G. Beattie, had Ramsbottom safety valves on the firebox and the steam dome half-way along the boiler barrel.

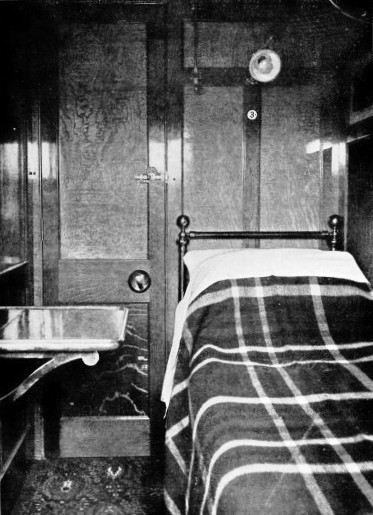

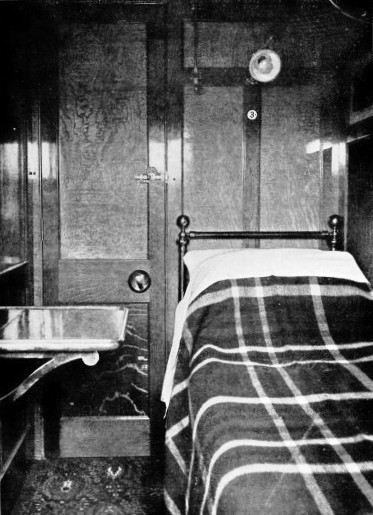

A COMFORTABLE SLEEPING BERTH ON THE PLYMOUTH MAIL

When Mr. William Adams became chief mechanical engineer he designed over a dozen classes of engines for the line, the best known being the powerful 85-in. coupled, with the 4-wheeled leading bogie (4-4-0), the frames of which project far in front of the firebox. In these he put a small steam valve in front of the main one to reduce the frictional resistance, and fitted his vortex blast-pipe to reduce the consumption of coal. In this the steam is discharged as a hollow cylindrical jet through a circular orifice enclosing an air-pipe which widens out into a large bell-mouth in front of the lower tubes, these being more difficult to clear by the blast owing to the vacuum having a stronger effect in the upper half, as shown by the upper tubes wearing away faster than the lower ones.

The steam blast, insignificant as it may seem, is the secret of the locomotive, and it was discovered by Richard Trevithick in building his first railway engine. Not caring to part with his waste steam until it had done a little more work, he used it for heating the feed-pipe, and led it into the chimney, perhaps at Rumford’s suggestion, to increase the draught by causing a vacuum in the smoke-box. For its effect to be satisfactory the blast must issue vertically from the very centre of the vertical chimney, the very slightest deviation to one side seriously checking the engine’s working. The smaller the outlet the sharper the blast, but too small an outlet causes back pressure in the cylinders, and thus the pipe must be large enough for the engine to work well. The size depends on the amount of steam the boiler makes and the engine uses, but is rarely less than 4½-in, and generally an eighth or two more, for even the difference of an eighth will make a difference in the coal bill; hence No. 335 of this line, which is a large engine, has a variable blast ranging from 4½ to 5½-in.

The last big 85 in. of the Adams design was No. 686, put on the rail in 1895, for in August of that year Mr. Dugald Drummond became chief at Nine Elms. No. 686, the last of the Adams engines, was the last with a number plate of raised figures on a red ground; No. 242, the first of the Drummond engines, was the first with a beaded rim round the chimney, like all that followed. The most noteworthy of these was No. 720, completed in 1897, the first of five others (369-373), a 4-cylinder engine with the front pair of wheels driven by the inside cylinders and the rear pair driven by the outsiders, the wheels being 79-in. and the heating surface, at first, 1664. As enough steam could not be got to work this double-single satisfactorily, a larger boiler was given her in 1905, the heating surface being increased to 1750. That year came another new idea, a class of thirty (Nos. 702-719, 721-732) being given 61 water-tubes 2½-in. in diameter, sloped across the firebox, and ending in the rectangular casing at the sides which distinguishes all such engines. The cylinders of this first group are 18½, stroke 26, driving wheels 79-in, heating surface 1500, grate area 24, and pressure 175. An improvement on these in appearance, owing to the wider space over the footplate and the absence of the little raised splasher covering the throw of the coupling-rod, was the class begun with No. 300, which, with the tender, weighed in working order 93 tons 14 cwt. One of these engines, No. 336, has brought the American express from Templecombe West to Waterloo, 112½ miles, in 104½ minutes.

THE APPROACH TO CLAPHAM JUNCTION (FROM THE LONDON END)

In 1905 another class of 4-cylinders (330-334) was introduced, with six wheels coupled, the drivers being 6 ft. and the bogies 3 ft. 7-in. In these engines, which complete with tender weigh 117 tons 17 cwt, the cylinders are 16-in. with a 24-in. stroke, and the heating surface, including that of the 112 water-tubes in the firebox, 2727 sq. ft., the grate area being 311 sq. ft. One of these, worked up to 1060 horse-power, attained a maximum speed on the Exeter to Salisbury road of 75 miles an hour. In 1907 came the bigger No. 335, the first of the South Western engines to be fitted with a pick-up water attachment, though no water-troughs had been laid down. This was of the same type, but with cylinders 16½ and stroke 26; and later on in the year came five more of these 6-coupled 4 cylinders, with a cylinder diameter of 15 and a stroke of 26, and 1920 sq. ft. of heating surface.

The reader is doubtless aware that in the ordinary locomotive boiler the water surrounds the tubes, while in the firebox-tubes the water is in the tubes; thus this 1920 sq. ft. of heating surface is made up of 140 for the firebox, 200 for the 84 water-tubes in the firebox, and 1580 for the 247 flue-tubes in the boiler. All these engines carry the Drummond feed-water heating apparatus, consisting of tubes in the well from which the condensed steam passes out into the air through the baffle-plates at the back of the tender, the water entering the boiler at a temperature only twelve degrees below boiling point.

Like the Lancashire & Yorkshire, the South Western uses dwarf locomotives for its rail motor-coaches. When engine and coach are in one, any breakdown of engine or coach means keeping the whole affair in the shops for repair, but by having them separate either can be in the shops while the other is at work - a system which has evident advantages. These little engines, with wheels a yard across, have 9-in. cylinders with a 14-in. stroke. They work at a pressure of 150, and have a heating surface of 347, of which 119 is given by the water-tubes.

IN THE ERECTING SHOP AT NINE ELMS

Placing an engine on its wheels.

All these engines were built at Nine Elms. For half a century or more these works had been doomed, but something always happened to delay the inevitable. So definite was the notice to quit that the men used to be warned on engagement against taking houses or lodgings for long periods, and yet things lingered on in the old style until the shift to Eastleigh became a standing joke. Even the removal thither of the carriage works failed to convince people that Nine Elms would one day cease from engine-building. Eastleigh, like Crewe, is a railway town pure and simple, and it started with a smaller nucleus, for on its site were only a few straggling cottages and a lane or two between the farm-lands where miles of rails run into and about as fine a group of workshops as can be found. At present there is space enough and room to spare, but whether that will be the case for long remains to be seen.

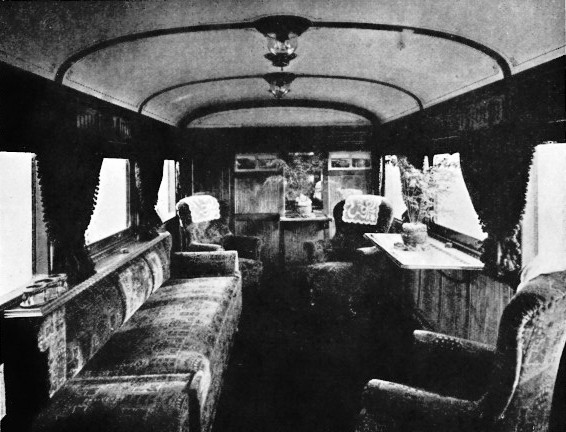

From the removal of the carriage-building department to Eastleigh dates a great improvement in the line’s rolling stock. The railway carriage has developed considerably since the days of the four old Bodmin & Wadebridge coaches, which are still kept as curiosities - the open thirds, the second-class with glass only in one panel, the gay blue and white composite, the buffers like boxing-gloves made of leather and stuffed with hair. Really the contrast is great between these survivals and the comfortable invalid or family carriage that can be sent through on to any line, the long sleeping saloons, the restaurant cars ready for any meal to which a name can be given, or the carriages that form the bulk of the ordinary trains. In the old days it was the fashion to make up a train of as many different varieties in colour and shape as possible, nowadays it is the train and not the carriage that is the unit, and the South Western expresses to Bournemouth, Cornwall, and elsewhere are equal in good looks to those of any of the lines to the north.

The South Western owns about 750 engines and nearly 19,000 carriages and wagons, and it runs nearly 20,000,000 miles a year, three-fourths of this being passenger traffic, which yields three and a third out of its five and a half millions of revenue. This is a much smaller proportion than that of the Brighton or the South Eastern, the greater amount for goods, and so on, being due, of course, to Southampton. In fact the South Western makes more out of its docks and shipping than any other railway company, more even than the Lancashire & Yorkshire, nearly £100,000 a year more than the Cardiff, £120,000 more than the Barry, and £80,000 more than the North Eastern and Great Central combined.

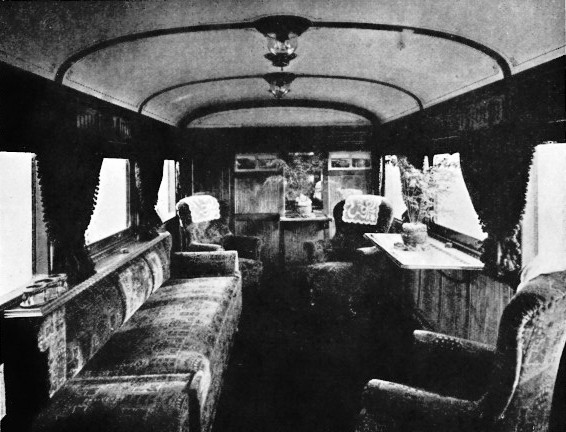

THE “FAMILY COACH” OR INVALID CARRIAGE

It has a fleet of eighteen vessels of its own, and has a half share in the Ryde boats from Portsmouth and Stokes Bay, the other half being held by the Brighton company. Two of its small boats do the service from Lymington to Yarmouth at the west end of the Isle of Wight, where, at each port, there are special slipways to provide for motor-cars running on and off the boat without being slung; another acts as a tender at Plymouth; the other fifteen plying between Southampton and the Channel Islands, and the northern ports of France from Havre to Roscoff. The amount of fruit and vegetables these Channel boats bring into the country can only be appreciated by those who have waited in them at Guernsey while cartload upon cartload comes pouring into them, or seen the whole cargo unloaded and dealt with at Southampton. It is not only Jersey potatoes that arrive in tons, nor cauliflowers, nor tomatoes, but almost everything, even strawberries, that are shipped in such quantities from Honfleur and St. Malo, that they not only fill the holds but occasionally half the deck. Only one thing seems special to any particular port, and that is those best of onions from Brittany, which come from Roscoff in baskets and are strung on to straw ropes in their last stage of transit. This is a curious little trade, for the men come with them, and after selling them from door to door in the chief cities, keeping a record of the address of every purchaser, meet at Southampton to return together by the same boat.

It was the South Western that gave the first trial to automatic signalling, the section of line being between Andover and Grateley on the main road to Salisbury. On that 6½ miles the apparatus began to work on the 20th of April 1902, the first to attract attention of several systems now developing so fast that the old signal-box with its signalmen is evidently doomed.

Who invented signalling is not clear, but it began with the hat and umbrella, and officially with the red necktie. That red neckerchief has done much good work in its time both by day and night, for at night it has been stretched over a lamp and given warning of danger to a train that was running into the scene of an accident. Once, according to Williams, a red pocket-handkerchief was used for train-stopping purposes by an Irishman trespassing on the Great Western, who seeing an express approaching ran a short distance up the side of a cutting and waved it at the end of a stick. The warning was not disregarded, the brakes were applied, and the train came to a halt. A hundred heads were thrust out of the carriage windows, and the guard had scarcely time to ask what was the matter before the Irishman asked to be given a bit of a ride. So polite a request was not to be denied, and the guard as politely answered, “Oh, certainly; jump in here”. The Irishman was soon ensconced in the luggage van, but instead of having the ride for his thanks, the guard handed him over to the magisterial authorities, who taught him that railway companies did not run expresses for giving lifts to practical jokers.

INTERIOR OF THE FAMILY CARRIAGE

Night signals seem to have begun with the tallow candle stuck in his window by a Stockton & Darlington stationmaster when he had a passenger waiting for the train. When the Liverpool & Manchester opened in 1830 the candle had got into a lamp and the necktie had become a flag. Four years afterwards the flag and lamp had mounted a post 5 ft. high; and in the course of the next three years the post had grown to 12 ft, the flag had become a disk, and the lamp had red glass in one of its panels. These disks, which were adopted because the flag always blew to leeward and the wind did not always blow from one direction, were turned parallel to the line for all clear, as a rule, but in some cases they were hinged at the top so that they could be worked like a lid.

Many of the railway companies have a few of their old signals kept as curiosities. At Gloucester the Great Western has quite a collection. In these the cross-bar appears, and it is at right angles to the disk. The mainline down signal has one disk and the bar with return ends pointing downwards, the up signal having no return ends, the signal at level crossings having ends pointing both up and down. On branch lines there were two disks and two bars, the smaller in each case being at the top, the ups having no return ends, and the downs having the down-pointing ends as on the main line. One signal, from Windsor viaduct, is a large disk with a wide rim; this was known as a tambourine, and it showed as a circle when upright and as a bar when horizontal. Another of the sort that continued in use on the Forest of Dean until 1904, is a plain flat bar with a swallow-tail at one end and a point at the other such as is now used by the platelayers; and another is the capstan worked by a lever which was used at facing points. It was from these that the present disk signals were developed.

In 1841 there was erected at New Cross the first semaphore used on a railway. The only originality was in the application, for close by on Telegraph Hill was one of the series of semaphores communicating with Dover. These were the old telegraphs for which the word - sema a signal, and phoros, bearing - was coined, and they had existed for half a century before Charles Gregory used them for the railway purposes. There is one at Portsmouth dockyard still, and they were on every prominent hill between the Admiralty and the coast for the transmission of messages in the style still used by the navy and army. In short, the semaphore was the telegraph, and we talk of the electric telegraph to distinguish it from the mechanical one from the motions of whose arm it got the beats of the needle and the dots and dashes of the Morse code.

INTERIOR OF VESTIBULE TRAIN USED IN THE PLYMOUTH DISTRICT

Just as the capstan signal was worked by a lever at the base, so was the semaphore. There were no leading wires, and the man had to be at his post, in both senses, when the arm was raised or lowered. This, however, did not last long, for on the North British a certain porter was given two signals to look after, and to save himself the trouble of walking from one to the other he brought along a pulley and some wire, and hanging a broken chair on to the lever as a counterweight, he fastened one end of the wire to the lever, passed the other through the pulley, and worked the signal comfortably from his hut. It was a simple thing, such as a boy would have thought of, but it started railway signalling as we know it, and that hut at Meadowbank was the first signal-box.

At many junctions the signalman was also pointsman, his duty being to move the sliding guide-rail and fix it into position with an iron pin; but when Sir Charles Fox invented the switch the rods were led into the signal-box, and the man had to look after two sets of levers, those for the signals and those for the points. The next step was the interlocking, which came in about 1843, though nothing much was done with it until 1856, when Saxby concentrated and interlocked the points and signals at Bricklayers Arms.

For some time the semaphore arm was worked in three positions; at the horizontal for danger, half-way down for caution, and straight down for safety; but now there are only two positions, the horizontal for stop and the half-right angle for all clear; just as at night the red light showed danger, the green caution, and the white that the road was open, until in 1876 the Great Northern discarded white as a signal colour, and, doing away with the cautionary, used green for all clear, the reason being the confusion between the clear light and the lights of the streets and houses in populous places, which were few and far between, and dreadfully dull, in the days gone by. The principle of the signal is not quite what might be thought. Safety is assured in cases of accident by the levers being weighted so that the arm is normally at danger and remains at it until interfered with. The weight has to be lifted, not released, to clear the road; and if anything goes wrong the arm automatically rises to the horizontal.

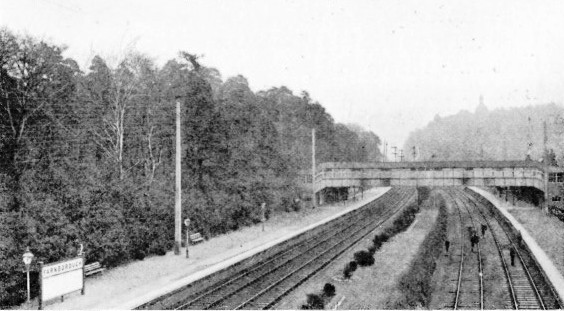

THE NEW STATION AT FARNBOROUGH

The lamp is clear glass, the so-called spectacles of one green and one red glass fixed to the short end of the arm working in front of the lamp and giving the colour; both colours, it is worth noting, being obtained from oxides of copper. The front of the arm, the side facing the approaching train, is red or red with a white bar, the white side, with or without a black bar, is the back, and, like the clear light of the lamp, is only of use as showing that the signal is in working order. The rule of the railroad is the rule of the road, the trains on a double track passing each other to the left, but the Greenwich line was laid out for the trains to pass each other to the right, and this was the practice adopted on the Newcastle & Carlisle up to June 1863, the year after it was absorbed by the North Eastern.

The ordinary signals are the home and the distant, the home having a square end, the distant having a swallowtail. The distant is cautionary only. A driver must not pass a home signal which is at danger, but when a distant is against him it means he must get his engine well in hand so as to be able to stop at the home if required. Another swallow-tail signal is the precaution; this generally has a ring round it, and when at danger it means that the platform at the station is already half occupied and that the incoming train must be pulled up within the space left vacant. The precaution is always near the station, while the distant may be a thousand yards away on a level, though nearer on rising gradients and in places where caution is necessary. All signals giving admission to a section of the line are square-enders, hence the starting signals at the stations have square ends. When there are two signals on the post at the end of a platform, one of which has a swallow-tail, they are worked from two different boxes; but when both have square ends they are frequently worked from the same box. When one of the arms on the post is larger than the other, the smaller arm is the caller-on; this allows the train or engine to pass with caution a short distance past the ordinary signal as far as the road is clear. Some signals away from stations are 75 ft. high and have a 5-ft. arm, but whenever a signal is over 45 ft. from the ground the Board of Trade require it to have an arm lower down so as to be readily discernible; the miniature arms close to the rail level are for the guidance of the fogmen.

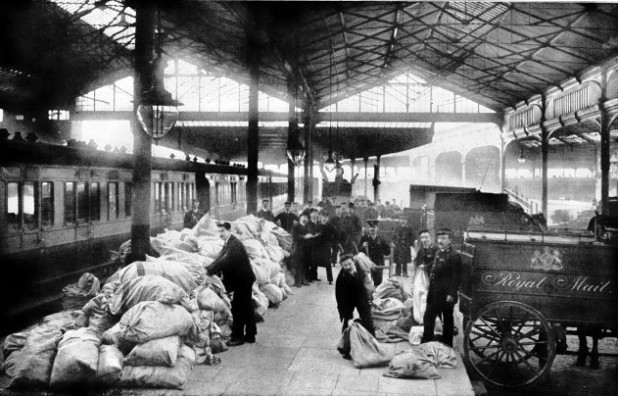

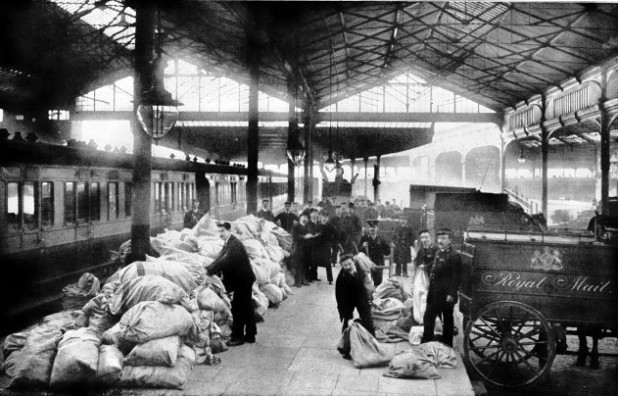

ARRIVAL OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN MAIL AT WATERLOO

The South Western suffers more than most lines from fog, owing to its large suburban traffic in the Thames valley. In one year it has exploded nearly 120,000 fog-signals. These cost less than a pound a gross, but as the food of a fogger is supplied at the company’s expense, a fog of a day or two’s duration may mean to a company a loss of £1000. What the total annual cost may be to the many British companies may be guessed from the fact that one firm alone, Kynochs, supply nearly two millions of fog-signals a year. Cowper’s detonating fog signal, then a novelty, was introduced on the London & Birmingham in January 1845, “to be placed on the rail to be passed over by the expected engine at about sixty yards distance in rear of the red signal”, as the general order had it.

Foggers are platelayers disguised in a thick overcoat. As their ordinary work cannot be carried on with safety in foggy weather, for in clear weather they are always busy examining the track or keeping it in repair, a man to every mile of single line, they go home, which is generally in electrical communication with the nearest signal-box, and come out in their turn for twelve hours at a stretch if necessary, half the men resting while the others are on duty.

When the arm of the signal rises to danger the fogman clips a detonator on to the rail so that the engine wheel will explode it by pressure. When the arm falls the detonator is picked up and the train passes without a report. Usually there are two detonators in case one should miss fire; but the code differs on different lines, though on all the danger lies in silence and not in the report which shows that the fogger is awake and doing his duty.

MELDON VIADUCT - LOOKING WEST THROUGH THE CUTTING

The signal itself is a large button built up of four parts, a dome of sheet iron, a base of tinplate, an anvil of malleable iron, and a clip of lead. The dome is stamped out of a 2¼-in. disk, which is pressed into the shape of a shallow basin, the base is stamped out and pressed into a lid with the rim the right size for the basin to fit into, the anvil is cast in the form of a triangle with a nipple at each corner and tinned, the lead is a strip soldered on to the back of the tinplate base. A percussion cap is fixed on each nipple, the anvil is placed nipples downward in the dome filled with gunpowder, the base is fitted on, and the whole is squeezed together firmly and judiciously, so that there can be no shifting or leakage, and it is given two coats of paint to ensure its being watertight. A fog-signal is an explosive of which the railway companies keep as few as they can get along with, but the makers undertake to be equal to all demands at an hour’s notice, and at the works the number of paper cylinders, in which the signals are packed like chocolate biscuits, is enormous during the winter months.

Automatic signalling may be said to have begun in the fog, the fogging system being evidently too primitive to last for ever. First came inventions for lessening the danger of the fogman’s occupation when he has to look after several roads and the fog is so thick as to make it difficult to make sure of the number of lines stepped over; for in many cases signals are exploded uselessly owing to the danger in attempting to pick them off when they are not wanted. One of these inventions, Woodhead’s, came into use in 1891; in this, by means of a lever and connecting layers, two signals are placed ten yards apart on the lines, and withdrawn if the semaphore arm is down when the train approaches.

Other inventors tried to solve the difficulty on the principle of the bell instead of the knocker. In the old days the noise was made at the gate to call the attention of the servants, in fact to give the summons where they were required; and all the neighbourhood heard. In these days we ring an electric bell, and give the summons where the servants are waiting to receive it; and only those hear whose business it is to hear. So with regard to signals in fogs. Why not inform those on the engine instead of every one in the train? Why not do away with the explosion on the line and give the signal on the engine? This led to giving the signal on the engine at all times, whether foggy or not; in other words, to audible signalling; and audible signalling, as the phrase is understood, is necessarily automatic.

ROYAL MAIL S.S. ALBERTA OF THE CHANNEL ISLANDS SERVICE

You can read more on “The London Brighton & South Coast Railway”, “The South Eastern & Chatham Railway” and “The Story of the Southern” on this website.