© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The North Eastern Railway

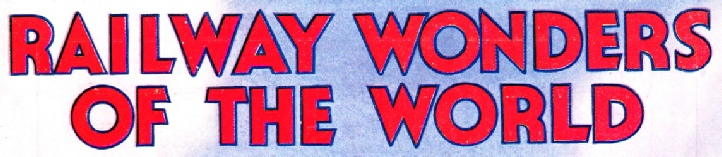

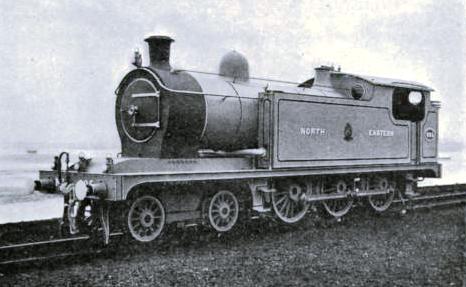

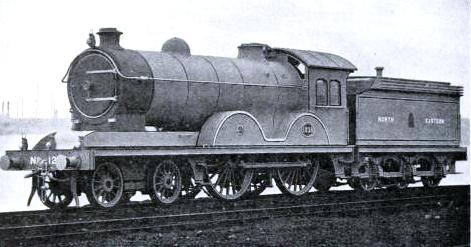

NORTH EASTERN RAILWAY EXPRESS PASSENGER LOCOMOTIVE, No. 730

DESIGNED BY Mr WILSON WORSDELL, M.INST.M.E.

THE North Eastern became first known under that name in 1854. It is an amalgamation of all the railroads that previously existed in the North Country, and as one of those roads ran past the cottage at Wylam before George Stephenson was born there, it is clear that the pedigree of the North Eastern goes further back than that of the Stockton & Darlington. We have, however, in the introductory chapter said all we have room to say about those early lines, and will here take up the story where the introduction left off.

As the Great Western was due to the difficulty of navigating the Thames, so the Stockton & Darlington owed its origin to the difficulty of navigating the Tees, ships taking as long to sail from the river-

In 1810 the Tees Navigation Company saved a couple of miles of the river journey by making the New Cut of 220 yards, but this was a trifle compared with the growth of the traffic, and it was evident that something else would have to be done. Meanwhile Edward Pease, of the woollen mills at Darlington -

Then Jonathan Backhouse, the Darlington banker, endeavoured to bring about peace between the rival factions by suggesting that the Tees should be made navigable up to Yarm, and that the railroad should run from Yarm to Darlington and on to the collieries, and in this proposal he was joined by Thomas Meynell, the squire of Yarm. Stockton would have none of this, and so the project was put to the vote at Darlington, when the majority was in favour of Pease’s plan of a line all the way. Having failed in their efforts at conciliation, both Meynell and Backhouse joined with Pease. Residing in the neighbourhood was Thomas Richardson, Pease’s cousin, a retired bill-

YORK STATION

Rennie’s survey met with the fate of so many surveys by his sons. The Bill was introduced into Parliament in 1818 and failed to pass; he had taken his line too near one of the Duke of Cleveland’s fox-

These terms were not accepted, and on the 19th of December 1818 Robert Louis Stevenson’s father, Robert Stevenson of Edinburgh, the lighthouse engineer, the man who built the Bell Rock and Skerryvore, was asked to make a fourth survey, which did not suit. The decision was conveyed to him in an amicable way; in fact all this business was done as pleasantly and quietly as possible, for remember this was the Quakers’ Line, nearly every shareholder being a member of that community to whom our railways are mainly due, and Stevenson continued to be consulted up to July 1821, when he was succeeded by George Stephenson.

It is not every one who has been to Yarm, but those who may find themselves in North Yorkshire might do worse than call in at the George and Dragon there, when they will find within a marble tablet that may surprise them. There, as the tablet records, on the 12th of February 1820 took place a meeting of the promoters of the Stockton & Darlington Railway, Thomas Meynell of Yarm in the chair, at which it was. decided to introduce into Parliament during the session of the following year the second Bill. In preparation for that Bill, Overton made another survey, the fifth; and on the 19th of April 1821 the Act was obtained. The first rail was laid by Meynell with great ceremony near St. John’s Well, Stockton, on the 23rd of May 1822. He was an excellent man for the work; pity it is that others have not been like him! Soon after the ceremony a boy with papers in his hand was shouting in Stockton streets, “Speech of Mr. T. Meynell. One penny!” A man bought one and found nothing but a sheet of blank paper. “Why, you little rascal, there’s nought here!” “No, sir”, replied the boy, “because he said nought!”

Shortly after the securing of the Act, Edward Pease was writing in his room when a servant announced that two strange men wished to speak to him. He was busy, and he sent them a message that he was too much occupied to see them. Hardly had he done so than he thought that perhaps he had been unkind, and he rose from his chair and went downstairs. Asking where the men were, he was told they were in the kitchen. Going into the kitchen he found them, and they gave their names as Nicholas Wood, viewer at Killingworth Colliery, and George Stephenson, engine-

Pease sat down on the edge of the kitchen table to listen to what they had to say, and Stephenson handed him a letter from Mr. Lambert, the manager of Killingworth, recommending him to the notice of Pease as a man who understood the laying down of railways. Pease read the letter and took stock of “Old George”. As he said afterwards, “There was such an honest, sensible look about George Stephenson, and he seemed so modest and unpretentious, and he spoke in the strong Northumberland dialect” -

In the conversation that followed Stephenson agreed that Pease had done wisely in proposing an edge railroad notwithstanding that, though any one might use it, as on the old Surrey line, the only traffic it could take must go on flanged wheels; but he asked for information as to what was meant by the vehicles being drawn “by men, horses, or otherwise” -

A POWERFUL TYPE -

The interview ended in Pease promising to support Stephenson’s application for the appointment of engineer, and agreeing to visit Killingworth and see what was going on. Stephenson was appointed, the edge rail was adopted instead of the flat rail, and Stephenson was desired to make a resurvey of the proposed route as soon as possible. This, the sixth and last survey, was at once begun by George Stephenson and John Dixon, assisted by Robert Stephenson as chainman; and in the summer of 1822 Edward Pease and his cousin Richardson went over to Killingworth to see and believe. Further, in 1823 the company obtained an amending Act giving them power definitely to use locomotives and to haul and carry passengers as well as merchandise.

The line was made as resurveyed from Witton, through Darlington to Stockton. There were stationary engines at Brusselton and Etherley; and it was from the “Permanent Steam Engine below Brusselton Tower” that the proprietors and their friends, “after examining the extensive inclined planes there”, started on the opening day, the 27th of September 1825. First came a man with a red flag, then “The Company’s Locomotive Engine” (Locomotion, No. 1, now the monument at Darlington, known by the ignorant, like that at Newcastle, as Puffing Billy, which it is not, Puffing Billy being at South Kensington), then “The Engine’s Tender” (described as a water-

That day Edward Pease’s son Isaac died, and in the silent room he heard the distant cheers telling him how his work had received its completion in the hour of his bereavement. That he was one of the best and greatest, “a man who could see a hundred years ahead”, has long been acknowledged, and by the publication of his diaries it has been amply confirmed. Unusually able, thoroughly genuine, and ever thoughtful for others, it is only natural that his native town should be proud of him, though in his lifetime he told the townsfolk plainly that he was not the father of railways, and absolutely refused to mount the high pedestal on which they would place him. To quote his own words, “Does it not do me some injustice in rendering me more than justice?”

That day Edward Pease’s son Isaac died, and in the silent room he heard the distant cheers telling him how his work had received its completion in the hour of his bereavement. That he was one of the best and greatest, “a man who could see a hundred years ahead”, has long been acknowledged, and by the publication of his diaries it has been amply confirmed. Unusually able, thoroughly genuine, and ever thoughtful for others, it is only natural that his native town should be proud of him, though in his lifetime he told the townsfolk plainly that he was not the father of railways, and absolutely refused to mount the high pedestal on which they would place him. To quote his own words, “Does it not do me some injustice in rendering me more than justice?”

The line was single, with a loop at every quarter of a mile; with its four branches it was 36¼ miles long, and it cost £9000 a mile, that is about four times as much as George Overton had offered to make it for. When consulted as to the rails, Stephenson told the directors that though it would put £5000 into his pocket to supply the cast-

The Experiment was the first passenger carriage of the Stockton & Darlington, but it was not the first railway coach, for, to say nothing of Trevithick’s, one had been running for years on what is now part of the Glasgow & South Western. Indeed, the idea of railway carriages had already become so developed that, the very year the Stockton & Darlington opened, William Chapman, the engineer, at the meeting of the London & Northern Railway, had spoken of “conveying passengers with speed and convenience from place to place, which may be done in long carriages resting on eight wheels and containing the means of providing the passengers with breakfast, dinner, etc., whilst the carriages are moving” -

For some time after the opening day the Experiment was not drawn by an engine but by a horse. It was built by Stephenson at Newcastle from his own design, and was like a builder’s movable office on four wheels. There were three windows on each side, and the door was at the end; along each side ran a row of seats, and in the centre was a deal table on which a candle was placed to lighten the darkness. This Experiment is shown as forming part of the train in the pictures of the opening trip; but, according to the model and handbill at South Kensington, there was put on the line on the 10th of October another Experiment. This was an ordinary coach-

In August 1823 the first piece of land was bought in Newcastle for the Forth Street Works, destined to be known all over the world. Stephenson, recognising that the workmanship of his engines might be improved upon, had resolved on having a factory of his own, and talking over the matter with Edward Pease offered to invest the £1000 he had received as a testimonial from the coalowners for his invention of the safety-

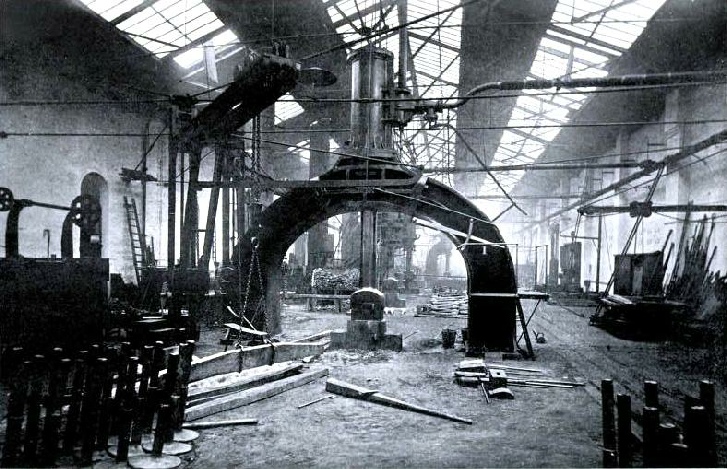

THE FORGE AT THE GATESHEAD WORKS OF THE NORTH EASTERN RAILWAY -

This engine had two vertical cylinders, placed fairly deep in the boiler, 10-

The fourth, fifth, and sixth engines built at Forth Street were Nos. 2, 3, and 4 of the Stockton & Darlington, known as the Hope, the Black Diamond, and the Diligence. No. 5 was the Stockton, built by Wilson of Newcastle in 1826. Wilson was so deeply impressed with what he called the dangers of coupling-

Hackworth, like Stephenson, was a native of Wylam, having been born there on the 22nd of December 1786. He was a smith, we may say, from the commencement, quite a Wayland Smith who could do anything with metal. He had a hand in building Puffing Billy, and for twenty-

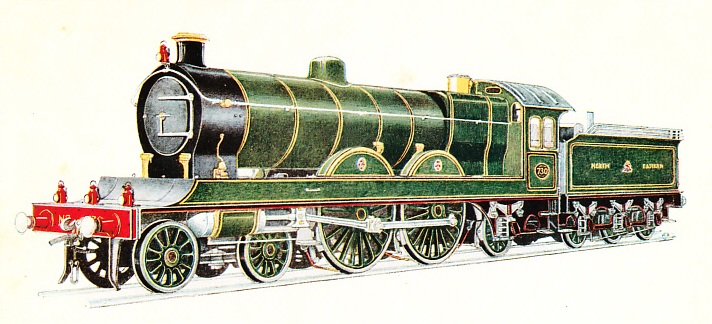

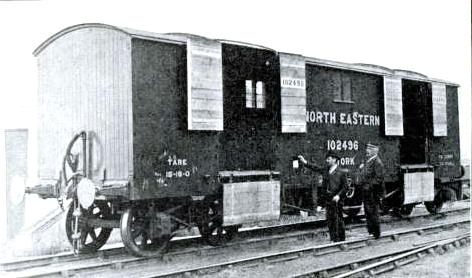

NO. 695, A HEAVY TANK ENGINE FOR LOCAL TRAFFIC

At the same time as Wilson delivered the Stockton. Stephensons delivered the Experiment, No. 6 of the railway list. This was the first 6-

No. 7 was Stephensons’ first Rocket, not unlike the Experiment; then followed No. 8, Hackworth’s Victory, built in 1829 at Shildon, no longer engine-

The Stockton & Darlington soon began to thrive some of its prosperity being due to the clause in the Act inserted at the instigation of George Lambton, afterwards the second Earl of Durham. This clause, limiting the rate for all coals carried to Stockton for shipment to a halfpenny a ton per mile while fourpence a ton was allowed for all other coals, was to protect his own coal trade from Sunderland and the northern ports, it being so low he thought as to render all competition hopeless.

Edward Pease had calculated on sending 10,000 tons a year to Stockton, and to his surprise -

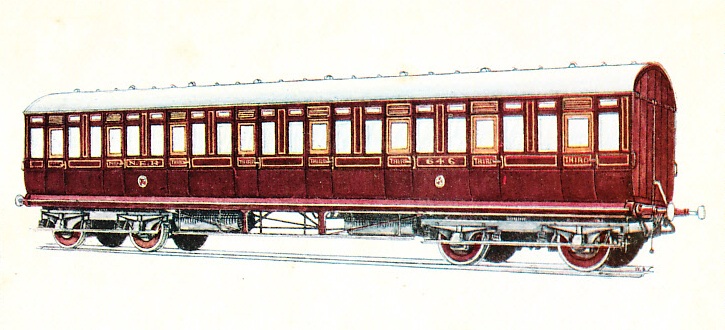

THIRD-

A committee of the corporation was appointed in 1832 to consider the matter, and one of the members of that committee was George Hudson, who set to work to learn all he could about railways and how to manage them. It was not railways that put him on the corporation, but the corporation that put him on railways. He would have been Lord Mayor of York if railways had never existed; no man ever had a more honourable introduction to the mysteries of railway finance. In 1827 he had been left by a relative a legacy of £30,000; in 1833 he had founded the York Banking Company, of which he was the first manager, and that year he had become the head of the Conservative party in York. Whatever he did he was throughout thoroughly devoted to his native city, and in defending the two great systems with which he was chiefly associated, the Midland and the North Eastern, he did what he thought best for its interests as well as his own.

Nearly three years elapsed without any decision being come to by the corporation committee, and then, in the summer of 1835, Hudson went for a holiday to Whitby, where he met George Stephenson and heard the latest railway news at first hand, particularly as regards the projects which affected York. On his return he reported to his committee what had passed, and acting on his advice they withdrew from their intended support of a direct line to London and contented themselves with helping in the promotion of the much less risky short line from York to Normanton to join the North Midland.

This was the York & North Midland, and in it Hudson invested the whole of the £30,000 that had come to him as a windfall. At the same time the committee decided to support the Great North of England, an imposing title which merely meant a line from York to Newcastle, or rather to Redheugh on the south bank of the Tyne, which passed through Darlington. Both these lines were wanted, both were authorised, and both were surveyed and engineered by the Stephensons. The York & North Midland was opened in 1840. The York to Darlington section of the Great North was opened in 1841; the Newcastle to Darlington, built by a separate company, in 1844.

FIRST-

The amalgamation of these two made the York & Newcastle, and when this joined the Newcastle & Berwick, the company became the York, Newcastle & Berwick, which in 1854 absorbed the York & North Midland, the Leeds Northern, and the Malton & Driffield to form the North Eastern. What the history of these companies had been up to then may be gathered from the speech of the chairman, Mr. James Pulleine, at the first meeting of the North Eastern on the 29th of August 1854, when he congratulated the shareholders on assembling “as one body instead of being engaged in unfortunate disputes, competition, and minor jealousies by which particular classes of traffic were guided to particular districts, instead of being carried in a way which would be of service to the whole”.

The York & North Midland was an easy line to make, the engineering features being in no way noteworthy, and the York to Redheugh -

It was the South Devon over again, only more so. Proposed for locomotives it would have been laughed out of the committee room, but for the atmospheric it was a different matter, and never was there a scheme that afforded a finer field for a conflict of opinion, especially when a prime minister, Sir Robert Peel, led the atmospherics and made the matter almost a party question. Fortunately the Conservatives, with Hudson prominent in the background, for he was to enter Parliament a few weeks afterwards, formed a cave, and on the 31st of July 1845 the Bill passed and Brunel’s people were saved from losing their money; and so delighted were the Newcastle men at the defeat of the broad-

FIRST-

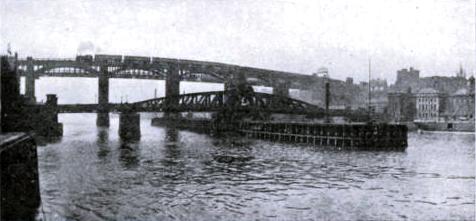

The engineer was Robert Stephenson, and the works were soon put in hand. To begin with there was the Tyne to be bridged by the famous High Level. The Newcastle corporation had insisted on the bridge carrying a road as well as a railway, and this was easily and ingeniously arranged by putting the railroad on top. Every one knows the bridge with the railroad on the bows and the high road on the strings. When it was begun there had been more than 25,000 railway bridges built in this country during the preceding fifteen years, and there was plenty of experience.

Down in the bed of the river went the piles under the fearful punching of Nasmyth’s new steam pile-

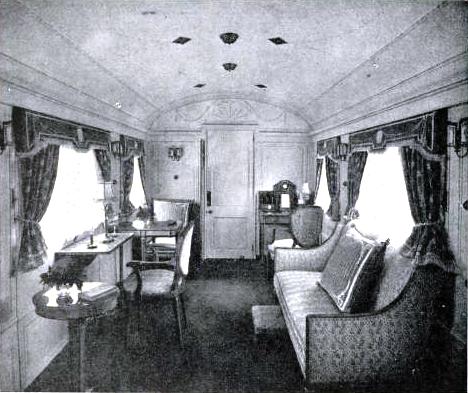

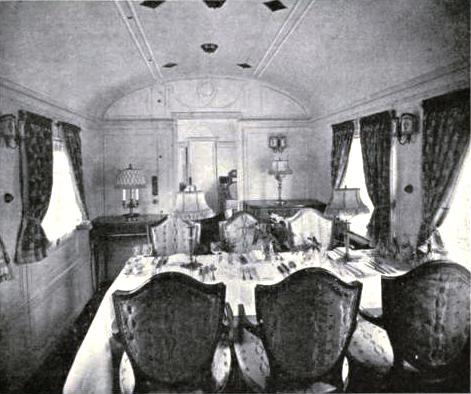

THE QUEEN’S CAR -

Then the coffer-

Each of the six arches of 125-

There are three sets of rails on it, and no bridge was more used; indeed the traffic over it increased and increased until 800 trains and light engines were crossing every day, and then it became necessary to build another. In building it Robert Stephenson’s assistant was Thomas Elliot Harrison of the Great Western 10-

THE QUEEN’S CAR -

When Stephenson built the older bridge the Tyne could almost be forded at low water, but now the Tyne Commissioners have dredged and dredged until there is a channel 28 ft deep and a tide range of 15 ft, so that bridge-

The bridge is not only noteworthy for itself but for the improvement of which it formed part. Formerly trains crossing the High Level into Newcastle Station had to come out by the way they went in. Now the station has been enlarged so that the East Coast trains can run through it, and coming from the south they cross the new bridge, enter Newcastle Station on the west and leave it by the east on their way to the north.

Newcastle is much the largest station on the North Eastern, though York is often said to be so; it has 15 platforms, nearly 7 acres of it are under glass, and nearly 850 trains enter it in a day. It has one of the largest signal cabins in the country, there being 259 levers with space to increase to 300, the levers being small owing to their being worked on the electro-

Another great bridge in which, as in the High Level, the railroad is carried on top of the roadway, is also due to Mr. Harrison. This is the one at Sunderland over the Wear, which has the heaviest span in Britain. In the main bridge are four spans, the river being crossed 85 ft above high-

AN IMPORTANT GOODS STATION, HULL.

At the other end of the Newcastle & Berwick was the Border Bridge built by Robert Stephenson. This is a noble viaduct of 28 arches. The old picturesque bridge, 17 ft wide, built in the early Stuart days -

Its name is the Royal Border Bridge, from its having been opened by Queen Victoria in 1850, but it does not cross the Border. Berwick, though on the north side of the Tweed, is in England, not Scotland. It is the extreme north-

In 1839 there had been opened the Newcastle & North Shields, from Pilgrim Street to that smoky seaport, and the same year there was opened throughout the Newcastle & Carlisle, the Act for which had been obtained in 1829. This went by Hexham and Haltwhistle to the canal basin at Carlisle, where the goods were transhipped to and from the vessels trading with the Solway. Westward it went through Wylam and the Stephenson country. At Blaydon it joined the Blaydon, Gateshead, & Hebburn, which it bought, and at Redheugh was the Brandling Junction, opened in September 1839, which went through Gateshead to South Shields and Monkwearmouth.

The Newcastle & Carlisle -

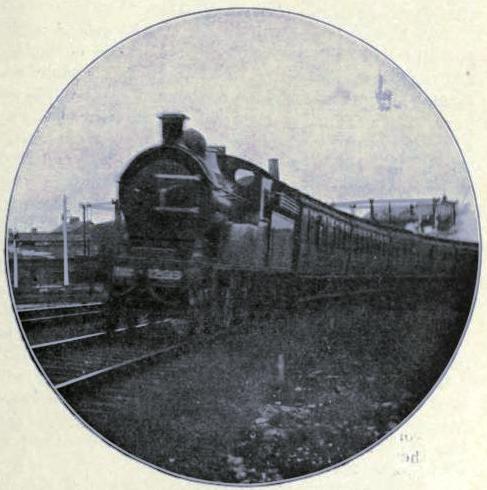

THE FASTEST TRAIN IN BRITAIN -

But in the beginning there was more danger behind the engine than in front of it, for our old friend Nicholas Wood, the engineer of the line, tried to run round the curves more easily by having one wheel of each pair fitted loose on the axle to allow of its moving inwards or outwards. To quote his own words, “the axle was turned very accurately and then there was a groove cut in the axle, the nave of the wheel was bored to fit the axle and a groove cut in it, and then a piece of steel interposed between the groove of the axle and the wheel, so that the wheel could move in and out and not turn round the axle” -

The Newcastle & North Shields and its extensions, in fact all the branches east of Newcastle, are now electrified, and the North Eastern and Lancashire & Yorkshire are running fairly level as by far the longest electric lines we have, sixty miles and more of each of their tracks being so arranged as to be workable either by steam or electricity. The North Eastern has about 60 electric motors and 2000 steam locomotives to run their 30 millions of miles a year on its 1700 miles of road, hauling 60 million passengers, 50 million tons of minerals, and 15 million tons of merchandise in its 113,000 wagons and coaches. In the beginning it looked for its chief profit to minerals and merchandise, and it has had it so all through its career. The character of its main source of income was not without its influence on its early engines, when engine-

Gateshead, the locomotive headquarters for so long, will soon be used only for repairs. When York locomotive works were closed those at Darlington were enlarged; and they are to be further enlarged that all the engines may be built there. The Stockton & Darlington, which then had some twenty branches, was absorbed by the North Eastern in 1863, and the old works at Shildon are now used as wagon shops in addition to the carriage and wagon works at Heaton and York.

The engines of the separate companies, excepting the Stockton & Darlington, were of the stock patterns of private firms, but after the amalgamation, when the North Eastern began in name, a few distinctive details appeared, though not many of them. The East Coast service, as we now know it, dates from 1870 when the extension from York through Selby joined the Great Northern at Shaftholme, instead of the route being by way of Askern, and it has always been that on which the best engines have been used. Here again, however, there is a qualification, for the Great Northern, under running powers, brings the trains to York, so that the North Eastern work is done from York northwards.

THE NORTH EASTERN AND LANCASHIRE & YORKSHIRE EXPRESSES, NEWCASTLE-

When the route was opened the engines were the Fletchers, with cylinders 17-

Mr. T. W. Worsdell began his tenure of office by building No. 1329. This was a single, 4-

A 25-

The larger group of 4-

In 1890, after putting some 250 of his compounds on the rail, he was succeeded by Mr. Wilson Worsdell, who in time began to build compounds on the Smith system as already described. He it was who introduced that powerful type the 10-

EXPRESS PASSENGER LOCOMOTIVE NO. 1238.

This was an advance in size and power, and No. 2111 was larger. She is a simple, of course; her 6-

The North Eastern carries more goods and minerals than any of our home railways, and ranks third in length. Northumberland and Durham it has to itself, and most of Yorkshire. Look at its map in which is shown the hill-

Berwick, Coldstream, Kelso, to reach which it crosses the Border and from which it could be run on Glasgow way if worth while; Carlisle, tapping Allendale and Alston Moor on the way; Weardale, and Teesdale up to Middleton reached through Barnard Castle -

Then there is the branch coming in at Eryholme from the Richmond that gave its name to West Sheen on the Thames to make it better known. In the valley of the upper Ure starts the branch from Hawes; and in the valley of the same river, lower down, that from Masham; down the Nidd runs the Pateley branch; down the Wharfe that from Ilkley -

York is now recognisable from afar by its water-

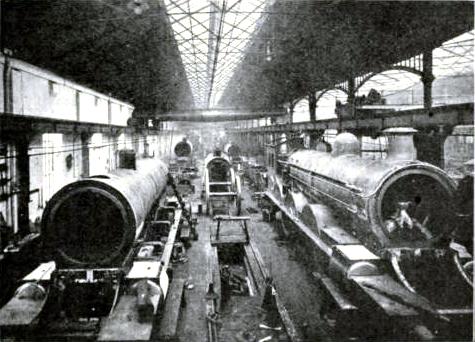

NO. 1 ERECTING SHOP AT GATESHEAD -

The longest non-

Passengers on the North Eastern are quite overshadowed by minerals; while it carries ten times as many thousand tons of passengers as there are days in the year, it deals with almost as many million tons of minerals as there are weeks in it. Not only are the coals distributed inland, but they are shipped in large quantities from the North Eastern’s docks. There is Tyne Dock, for instance, where they load a ship at the rate of 500 tons an hour and send away 6 million tons in twelve months. Then there are Blyth where the coal shipments are about half as great, though they have been going on for more than three hundred years; and Dunston where about half that quantity is shipped; and the Hartlepoole, the fourth timber port in England, that ship the same quantity as Dunston; and in addition there are Monkwearmouth, Sunderland, and Hull. Tyne Dock, for the coals outwards and the timber, grain, hemp and flax, inwards, has sixty acres of water; Hull has a hundred acres for coals and forty for the timber trade; Hartlepool has eighty for coals and nearly sixty for timber; and there are thirty-

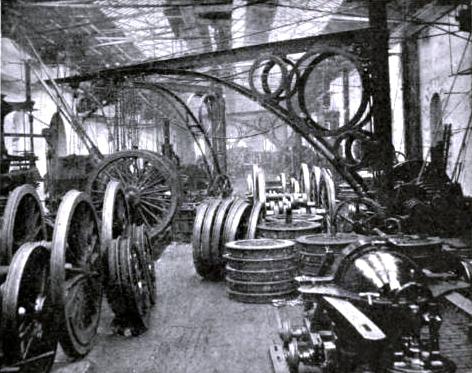

MACHINE SHOP AT THE GATESHEAD WORKS.

Those who are interested in steep gradients will find many of them on the North Eastern mineral lines, including several still too steep for locomotives. Near Battersby is the steepest, that at Ingleby, rising 1 in 6 for a thousand yards, a nice little climb of 500 ft; at Waldridge there is one of 1 in 25 worked by wagons in trains of nine, the full wagons attached to a wire rope by means of which they haul up the empty ones, and so steadily do they work that they take down over 9000 tons a day. The steepest gradient used by passenger trains is that at Kelloe, between Hartlepool and Ferryhill, where the rise is 1 in 36 for three-

Corridor carriages began in this country on the North Eastern, the first being a first-

NORTH EASTERN RAILWAY THIRD CLASS CARRIAGE No. 646

It may be a small matter, but it is worth remembering that trains of this sort cost £12,000 each to build, and, with the more elaborate decoration, they cost more every year. Nowadays the North Eastern standard passenger coach is 53½ ft long, the electric cars being 18-

Third-

The North Eastern has always considered the cyclist, and been happy in its efforts to encourage every other form of healthy recreation. Its excursion arrangements are almost as well thought out as those of the Scottish lines, but among its ticket novelties perhaps the boldest was the issue of coupons for a thousand miles during a year, each coupon being for a single mile, each book of a thousand costing five guineas ; and during the first year there were sold no less than 4200 of these books of first-

THE HIGH LEVEL BRIDGE AT NEWCASTLE.

In several ways it is the most practical of our lines. Fortunate in its monopoly, it has done its best to develop its business without litigation; friendly with all the companies around, it has been generous in its interpretation of what is meant by running powers, and has lost nothing by doing so. No less than seven other companies run into York after traversing over twenty miles of North Eastern metals.

This running of one company’s trains on another company’s line may seem a simple affair, but it has to be paid for, and few are aware of the vast amount of work it entails behind the scenes. So far as passengers are concerned the visible sign of this is the ticket and the nipping. How often do we hear the holder of a frequently punched ticket complain of the damage the nippers have done! Little he thinks that every nip tells the Railway Clearing House the route by which he has really come.

It was in 1864 that the system of ticket-

THE WHEEL SHOP AT GATESHEAD

George Hudson, by his encouragement of through traffic by way of Derby and York, rendered the Clearing House necessary and first suggested it. Sir James Allport, then of the Birmingham & Derby, went a step further and proposed a system similar to that of the Bankers’ Clearing House; Robert Stephenson, then engineer of the London & Birmingham, the Birmingham & Derby, and the North Midland, had the matter explained to him by Allport, and at once grasped its importance, and energetically supported it at a meeting of the Birmingham & Derby directors at which Samuel Carter, the solicitor of the other two companies, was present; and he and Carter brought the matter before the London & Birmingham directorate, with the result that the chairman of that company, Mr. George Carr Glyn, afterwards Lord Wolverton, became the first chairman of the Railway Clearing House, and appointed Mr. Kenneth Morison, then of the London & Birmingham, its first manager.

Morison organised it, and on the 2nd of January 1842 the Clearing House began business in a small house in Drummond Street near Euston Station, with a staff of half a dozen clerks who had a very easy time of it -

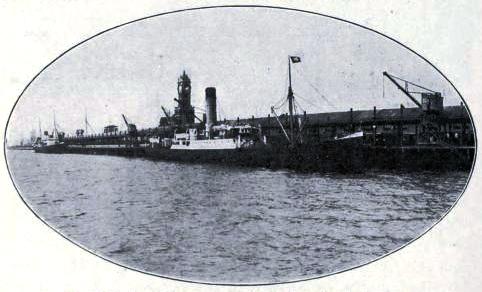

NORTH EASTERN STEAMER PREPARING TO LEAVE FOR ROTTERDAM RIVERSIDE QUAY, HULL.

You can read more on “The Great Northern Railway”, “The North British Railway” and “The Romance of the LNER” on this website.