© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The Glasgow & South Western Railway

THE SOUTH EXPRESS ON THE GLASGOW AND SOUTH WESTERN RAILWAY, LOCOMOTIVE No. 385

THE Glasgow & South Western begins its pedigree with a colliery line, the Act being obtained in 1808 for connecting the Duke of Portland’s collieries near Kilmarnock with the port of Troon. It was nine and a half miles long, and the company had a share capital of £55,000 with £10,500 in loans, or, as we should call them now, debentures. Opened in 1811, it was worked at first by horses, and it was the first passenger line, for on it was a passenger car very busy in the summer evenings and on holidays carrying to the “saut watter” and back the Kilmarnock weavers, who were in fact the first seaside trippers.

This line was made by William Jessop, and did not have tram-

Two years before the Kilmarnock & Troon obtained its Act -

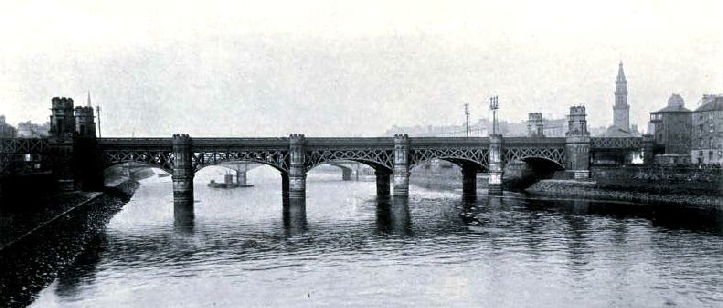

THE GLASGOW AND SOUTH WESTERN BRIDGE OVER THE CLYDE, AT GLASGOW

The scheme was a good one though it went awry. The harbour works were projected on a scale so grand for those days that in 1815 after the estimates had been exceeded they came to a standstill. Over £100,000 had been sunk in them, and Telford and Rennie wanted £300,000 more -

To carry the goods to and from the new port of Glasgow there was projected at the same time the canal. This woke up the Clyde Trust, and was the real cause of their Act of 1809 giving them power to make the river at least nine feet deep at neap tides between Glasgow Bridge and Dumbarton. Further, on the 12th of January 1812 Henry Bell’s Comet appeared on the Clyde to ply between Glasgow, Greenock, and Helensburgh, and the Comet was soon followed by the Elizabeth, and steam navigation had begun. This was a sore blow to the Ardrossan scheme, and when the harbour works stopped the canal stopped, so that it got no farther from Glasgow than Johnstone in the centre of Renfrewshire. It was this canal, known as the Glasgow, Paisley, & Johnstone, that endeavoured in 1830 to turn itself into a railway, and in 1883 succeeded in doing so by becoming part of the Glasgow & South Western.

ST. ENOCH STATION AND HOTEL, GLASGOW

Meanwhile in 1827 an Act was obtained for making the Ardrossan & Kilwinning, another colliery line on which, besides the coal wagons, ran a passenger van described in some quarters as a one-

When the Kilwinning was projected certain influential people in Glasgow began to discuss a scheme for a railway to Paisley, and when in 1835 Joseph Locke’s report in favour of a line up Nithsdale became public property, these cautious merchants answered with a plan for a route through Paisley down Nithsdale to Carlisle, as already referred to in the story of the Caledonian. Then followed the years of battle ending in the Paisley line going on as the Dumfries & Carlisle, to be opened throughout in October 1850 and become the Glasgow & South Western, whose first meeting was held in March 1851. But the line does not reach Carlisle; it stops eight and a half miles short of it at Gretna, which, as might be supposed by those who have heard of Gretna Green marriages, is just over the Border on the west bank of the river Sark that hereabouts divides England from Scotland; and it obtains access to Carlisle by means of its running powers over that short section of the Caledonian.

Carlisle Station, it may be noted, was originally built by the Caledonian and the Lancaster & Carlisle. In 1860 it consisted of a single platform for both up and down trains; now it is a joint station covering over seven acres, with seven platforms and fifteen roads occupied by no less than eight railway companies -

At Dumfries the Glasgow & South Western sends off one branch that forms the junction with the Portpatrick & Wigtownshire to Castle-

At Dumfries the Glasgow & South Western sends off one branch that forms the junction with the Portpatrick & Wigtownshire to Castle-

In length it is 467 miles; it carries over 15 million passengers a year, nearly 7 million tons of minerals, and over 1½ millions of miscellaneous goods; and it owns over 19,000 vehicles and about 400 engines, which taken together travel some 7¼ millions of miles, to say nothing of what is done by a few steam motors on the Catrine and Cairn Valley branches. Though much smaller than either the Caledonian or the North British, it is quite as well managed; and it has two of the best things in Glasgow, the St. Enoch Station and the St. Enoch Hotel. To Glasgow its main line is the northern portion of the Midland route. More than once in its history it has been on the verge of amalgamation; but that has not taken place yet, though there are some who see in the crimson colour of its coaches an indication of its future.

The old route to the south was fairly easy, but the new, which is ten miles shorter, would not have commended itself to Joseph Locke. This is very much of a joint affair, having been made by the engineers of the two companies in alternate sections. Leaving Glasgow it rises for 11 miles, four of which are at 1 in 80; then it is almost level for about 2 miles; and then for 11 miles it runs downhill, four of them being at 1 in 70, which is a steeper gradient than that at Beattock on the Caledonian. From Kilmarnock southwards the route is along the old track. For 21 miles it rises at 1 in 99, 1 in 200, 1 in 150 to New Cumnock, and from the summit it makes its way downhill to Gretna, which is 106¾ miles from St. Enoch’s, the whole distance to Carlisle being 115½.

Kilmarnock, where the Stewarton line goes off, is the second largest station, and the branches from it north and west interlace so freely that you can get there from Glasgow by ten different ways. One of the branches, by the bye, runs to Darvel and Strathaven on the Caledonian, the section from Darvel onwards being another joint production, and worked by the two companies alternately every six months.

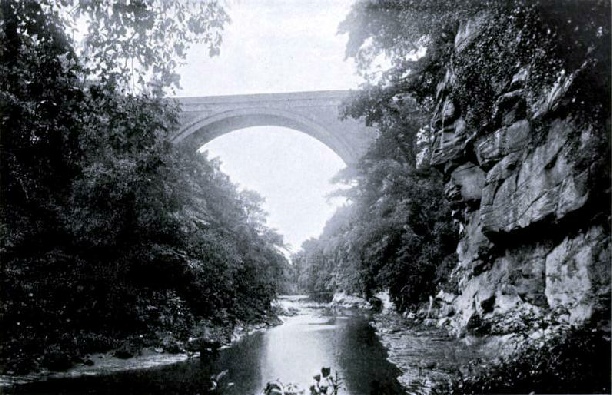

BALLOCHMYLE VIADUCT

The station being a high level one placed on an embankment and approached by a viaduct, nearly every one going north by the Midland route remembers Kilmarnock, which has been weaving bonnets ever since it originated the industry in the sixteenth century, and took on many other things, including carpets, for which perhaps it is better known, for here it was that Thomas Morton invented the three-

The Glasgow & South Western runs through the heart of the Burns country, and station after station bears some familiar name. Close to the tunnel at Mauchline, high up, is Mossgiel; and two miles south of Mauchline station the trains run over the noble viaduct of Ballochmyle, the most picturesque engineering feature of the line. With its graceful arch this makes a perfect picture, as it bridges the thickly wooded, precipitous chasm high above the river Ayr, which in winter flood still sweeps through the gorge as the lengthened, trembling sea that Burns described.

Another noteworthy feature is the Union Bridge, by which it crosses the Clyde at Glasgow, a substantial looking structure of five river spans of 75 ft, and two street spans of 65 ft, the cylindrical piers of which are of cast-

EXPRESS PASSENGER ENGINE NO. 384

There was nothing very remarkable about the early engines, but when the Settle & Carlisle was completed and the Midland obtained its through route to Scotland, Mr. James Stirling, then at Kilmarnock, produced for the Glasgow run the type of engine he afterwards took with him to the South Eastern. These were 4-

Mr. James Manson came from the Great North of Scotland as his successor, and, substituting a steam dome for the perforated pipe, evolved a new 6 ft 9-

DOWN PLATFORM, KILMARNOCK STATION

In 1866 the company were about to amalgamate with the Caledonian, the object of the West Coast companies being to shut the door of Scotland against the Midland. Had that happened the Settle & Carlisle would have been made in vain, and to thwart it the Midland opened negotiations with the Glasgow & South Western which went so far that the terms were arranged for the absorption of the Scottish line. The Caledonian and North Western opposed the Bill of 1867 for “this longitudinal amalgamation that had none of the public disadvantages of parallel amalgamation” with every weapon they could lay their hands to, and though it passed the Commons it was thrown out by the Lords. And it was during these times that the Glasgow & South Western took on the Midland manner which, under the subsequent understanding, it retains.

Though independent, the two companies work together with excellent results, one of which is that the Glasgow & South Western handles its parcel business as well as, or better than, any other Scottish railway company; and that is saying much. The writer’s first experience of the line was when one day in Glasgow he had occasion to send a heavy parcel of books to a suburb south of the Thames. Within a stone’s-

KILMARNOCK -

Like the other Scottish companies, the South Western, as it is always called north of the Border, adopted the shop parcel system, which might well be introduced generally. At the railway station you buy a packet of labels at a penny each, the labels being perforated through the middle. You wander about through the town, any town, buying what takes your fancy, and at the shop you tear off half a label, which is stuck on to the parcel. There is nothing more to worry about. When you catch your train at the station you go to the cloakroom, and there you are handed all your parcels in exchange for the other halves of the labels. Think of it! No struggling about with brown-

Its first Glasgow terminus was Bridge Street; then the line crossed the Clyde to Dunlop Street, and in 1876 it went a little bit farther on to the station named after St. Mungo’s mother. How “S. Thennow, vidow mother of s. mungo vnder King Eugenius in scot. 445,” whose day is the 18th of July and whose father was King Loth of Northumbria, in after days became, through error in transcription or difficulty in pronunciation, Thenaw, Henaw, and eventually Enoch; and many other things, mostly unbelievable, about her, including the grand finale of her sinking boat being borne up the Firth of Forth on the backs of a shoal of fishes, is duly recorded in George Macgregor’s History of Glasgow (one of the books that went in that parcel). What we are concerned with here is that one of the gates of old Glasgow was named after her, and just outside it was the little chapel which gave its name to the square where there is now one of the finest railway station fronts in existence.

PRINCE’S PIER, GREENOCK

It is as distinctive as St. Pancras, and not unlike it in its high level approach. In style the hotel is described as Early English, not, however, so early as that of the days of King Loth; and it is really a fine, suitable building 240 ft long and 130 ft high. The best idea of its accommodation and equipment is obtained from the fact that the kitchen is 85 ft long, 32 ft wide, and 20 ft from floor to ceiling. At first the hotel extended all along the front, where it may again go, but the station itself was not long since nearly doubled in width, and so overlaps it. There are now fourteen roads and twelve platforms, whose faces total up to nearly two miles; it covers 13½ acres, and each of the two spans, whose ribs weigh 54 tons each, is 205 ft across. In some ways it had its influence on the design of the Brighton Company’s new Victoria, the signalling being electric on the same system and there being a subway arrangement for parcels.

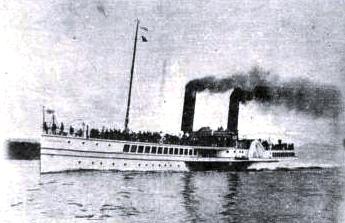

The Glasgow & South Western has its fleet like the Caledonian, and it is as numerous. It began with its steamers almost as soon; and it runs them, as it has done all along, from Greenock, though some of them work from Fairlie and Ardrossan. The Juno, Jupiter, and Mercury are as well known as MacBrayne’s Columba and Iona, or the turbine-

THE GLEN SANNOX CROSSING TO BRODICK

You can read more on “The Caledonian Railway”, “The Railways of Caledonia” and “The Story of the LMS” on this website.