© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The Great North Road of Steel

An Epic Story of the Courage and Endurance that Built Britain’s Highway to Scotland

THE TEN A.M. EXODUS, showing the five north-

TEN a.m. is not the usual hour for the regular enactment of a drama. Neither is a busy railway platform the usual place for it. But it would be difficult to find elsewhere in the pageant of modern travel a more inherently dramatic scene than that enacted daily at ten a.m. on the number ten platform at King’s Cross.

At that hour, precisely, the “Flying Scotsman” is due to leave for the North -

In the face of such an accomplishment, year in, year out, the bare figures of the time-

Safety, rapidity and reliability -

The exact distance covered between the London terminus at King’s Cross and Edinburgh is 392¾ miles, and the journey takes seven hours, forty minutes. This means that the average speed from start to stop is well over 50 miles per hour -

During the summer months, when the “Flying Scotsman” has to be run in several sections, the train accomplishes almost four hundred miles without a stop -

To enable the relief crew to take over, the engine is provided with a specially constructed tender, which has a passageway running through it. In this way it is possible to reach the footplate of the engine from the train itself, and thus the engine crew can be relieved without stopping the train.

Some idea of the exacting duties of an engine crew can be gathered by considering the amount of coal required -

A Huge Load

The magnitude of the task accomplished by the engine may be gauged from the fact that the weight of the train, when full of passengers, is approximately five hundred tons. Only about twenty tons of this weight represent that of the passengers and their luggage, but there are two hundred and sixty tons of iron and steel, and well over two hundred tons of timber. Five hundred tons to be carried four hundred miles!

The twice-

It is fitting that such a world-

In the contrast between this locomotive -

To-

The weaving of the network of steel which covered Great Britain and spread to every continent in the world was the product of many minds.

On the technical side men like Trevithick, the father of the steam locomotive, the Stephensons -

Fortunes were made and lost in the financial battles which ensued and great figures dominated railway development, linking the cities and planning the routes along which the lines now run.

One picturesque autocrat, omnipotent for a few months, was George Hudson, the “big swollen gambler”. He was a financial prodigy, having amassed a fortune while still in his twenties. Hudson foresaw that the new method of travel would have a long fight for recognition unless energetic stimulation was applied. He decided to apply it. At a critical moment in railway development, before public confidence had been gained, he stepped into the arena to uphold the cause of the railways.

He was a public figure, eagerly followed, and from the day he championed steam locomotion lethargy and indifference to the railways were dispelled.

He was a public figure, eagerly followed, and from the day he championed steam locomotion lethargy and indifference to the railways were dispelled.

So magnetic was his influence that there followed a swing of the pendulum, an outburst of wild and reckless investment in which restraint and discretion were thrown to the winds.

Lost Fortunes

Speculators in all walks of life, forgetting the lessons of the South Sea Bubble, risked their all in the rush to get rich quickly. For months there raged a railway boom, when money poured into the new projects from all over the country; but finally the bubble burst, with an inevitable aftermath of ruin.

George Hudson’s part in trading upon the public’s credulity has been fiercely assailed. But it was he who strengthened the railway movement at the very time when a strong impetus was imperatively needed. And although thousands of speculators suffered at the time, posterity has benefited.

Despite his courage, his foresight and his brilliant grasp of the possibilities of railway development, George Hudson had that common failing of the autocrat -

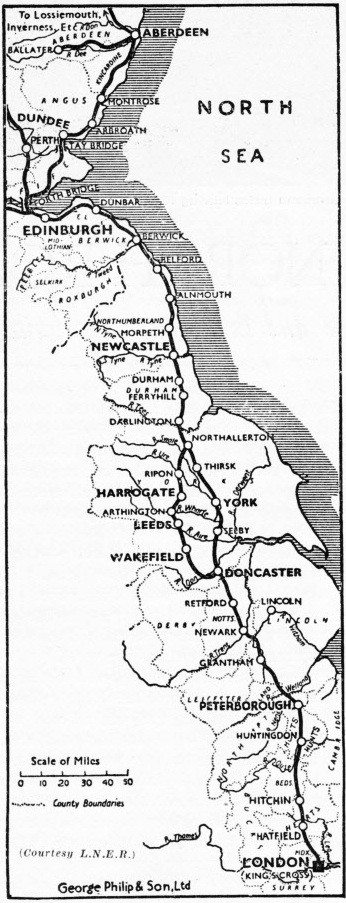

TWICE A DAY this route is traversed by the “Flying Scotsman”, the up and down trains always passing one another at the same point near York, and at the same hour.

The Midland Railway was the pivot on which his strength rested, and his plucky and resourceful handling of his projects enabled him to spread a comprehensive network of railways covering north-

His great objective -

But other forces were at work, especially in the territory east of the Midland’s line between London and York, which was awaiting development, and promised a rich reward. A new line here, with connexions to the north, would follow the route of the Great North Road, where the stage coaches had flourished for so long. So a scheme was evolved to build a railway from London to York.

A similar project had attracted another group of business men, who planned the Direct North Railway. And for two years there was bitter strife between these two, until it was realized that Hudson was benefiting by the dissensions of his rivals. So the London and York and the Direct Northern projects were fused into one formidable concern demanding a Parliamentary charter. Such competition threatened Hudson’s schemes with ruin.

A long legal fight ensued, and at one time George Hudson was spending over £5,000 a day to maintain his hold. But the opposition, after many setbacks, played a trump card by asserting that on their line coal from Yorkshire to London could be carried direct and more cheaply. It proved to be a telling argument, and the charter was granted.

Outmanoeuvred, George Hudson made a memorable flank attack before construction of the new railway had fairly begun. He took advantage of his Midland line’s penetration to York to make that city the base of the new attack.

Between York and Newcastle there were various stretches of railway without through connexions, so Hudson determined to complete a chain by making new links where necessary, thus providing an unbroken line from York to the Tyne.

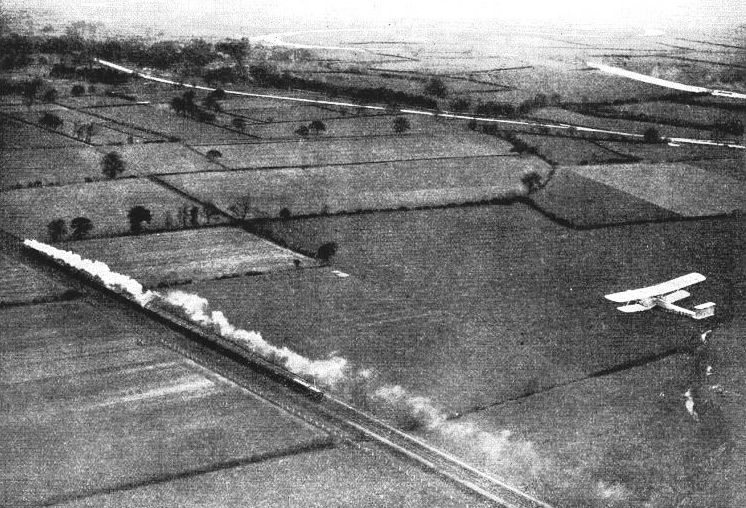

FLIERS BOTH. This remarkable picture shows the “Flying Scotsman” accompanied on its northward journey by the Imperial Airways liner, “Heracles”. On this occasion wireless telephone communication was established between train and ‘plane, first time in history that such a feat had been attempted at a speed of sixty miles per hour.

This made possible a continuous route from London to Newcastle, and the three hundred miles -

There was intense enthusiasm when the new route was opened, and the inaugural train was received at the Tyne terminus with frantic cheering and flag-

His rivals, however, continued to press forward with their Great North Road, and the question of inter-

His traditional methods continued to influence railway development long after his own retirement, and just as he had fought for the traffic between London and the Tyne coalfields, so his successors waged war to secure the Scottish traffic.

The Great Northern was regarded as an interloper in this field by the London and North Western, while the Midland also resented the filching of traffic from what it considered to be its own field. So these two lines made common cause against the Great Northern, and attempted to isolate it.

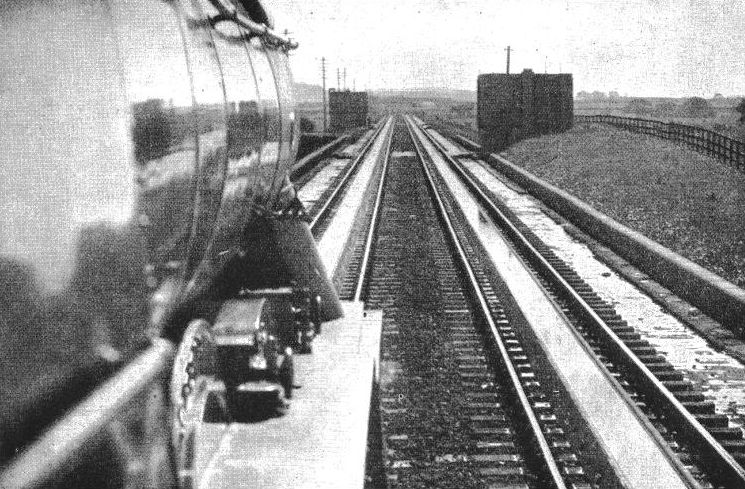

A LONG DRINK. A locomotive picking up water at speed from a trough laid between the lines. A scoop is lowered from the engine tender when the train reaches the trough, and water rushes up to replenish the tank. The troughs are automatically refilled as required from the large containers seen at the side of the line. These tanks contain chemicals which soften the water and so prevent excessive scaling in the locomotive boiler.

They acquired control of many neighbouring smaller lines which normally would have acted as feeders to the Great Northern, but which now operated to starve it. But they failed to acquire the vital links which carried the Great North Road beyond the Tweed.

It was here that the latter broke free of the last shackles, and finally an amicable settlement was arranged giving continuous communication between London and Scotland by the East Coast route.

About this time the fight for territorial rights by the various railways afforded some amazing incidents that are still legendary among railwaymen. There was the “battle” of Nottingham, for example.

When the Great Northern secured an entry into this city its coming was fiercely resented by the Midland faction. The first passengers were treated to such indignities that they must have sighed for the comparative calm of the old stage-

Similar liveliness marked the occasion when the Great Northern secured running rights to Manchester by completing an arrangement with the Manchester and Sheffield Railway. Passengers arriving in Sheffield by one of these new trains found themselves surrounded by hostile crowds and exposed to the direst threats of what would happen if they dared to travel by the interloping line again.

The Fight for Fares

Apparently the hardiness of the Great Northern’s passengers was equal to this, for the next move was a rate war, in which travellers were tempted by low fares.

This was a more serious deterrent to the Great Northern than was violence, since their income from fares fell enormously, and at one stage of the fight the passenger fare from London to York was only five shillings.

The heavy loss to the Great Northern can be estimated from the fact that it was costing them more to run over one short section of a rival line than they were receiving for the whole journey from London to York. And how they would have weathered the storm is still a matter of conjecture, because another factor intervened and changed the whole situation with dramatic suddenness.

This new development was an estrangement between the Great Northern’s rivals. The London and North Western had become alarmed because the building of bridges over the Tyne and the Tweed offered the Midland an alternative route to Scotland; so the alliance against the Great Northern was loosened, while a new struggle began between the former allies.

The London and North Western, tardily regretting the concessions granted in George Hudson’s day, refused to issue tickets at Euston to passengers who wished to travel to Scotland over the Midland route. To counter this move, the Midland made peace with its former enemy the Great Northern and obtained terminal facilities at their station, King’s Cross -

Another move in the railway struggle had meanwhile been taking place in the north-

It has been generally appreciated that the tendency towards grouping, so successfully employed by Hudson, was an inevitable step in railway development. But it is not so generally realized that the rivalry which existed before the large-

A good instance of the enterprising work carried out in these early days, when our railways were achieving adolescence, is the building of the Bramhope Tunnel between Harrogate and Leeds. It is well over two miles long, and occurs on one of the short lines launched when Hudson was “Railway King”. The proposal to build it was, indeed, a special object of his anger, since it threatened to provide a rival route between Leeds and the North, with a saving of fourteen miles.

His opposition was overcome, and the Leeds and Thirsk Railway -

The line runs through very difficult country, and the most formidable obstacle of all -

From the first the engineers were under no illusions as to the difficulties of the task, but their most gloomy forecasts fell short of the obstacles actually encountered. Their original tunnel as projected was to have been much shorter than the one which proved to be necessary. It was thought at first that a deep cutting would serve the builder’s purpose, but the experience of actual working conditions caused them to modify their original view, and the cutting was abandoned in favour of the longer tunnel, after considerable expense and time had been wasted.

When work began on the northern portal, the enterprise was considered one of the most ambitious and difficult ever undertaken by railway engineers. A double track was provided for, and the engineers had to sink no fewer than twenty shafts at various intervals, the depths ranging from 70 to over 400 ft.

The chief enemy was water, and time after time it drove the workers back, with loss of life. Standing in Otley Churchyard there is a remarkable monument to thirty men, buried in a common grave, who were drowned by the penetration of water into the workings. The monument is a reproduction of the northern portal of the Bramhope Tunnel, and it affords a striking reminder of the price in lives paid by pioneers of the railways.

Except for a slight curve at either end the tunnel is straight, and the arch is brick-

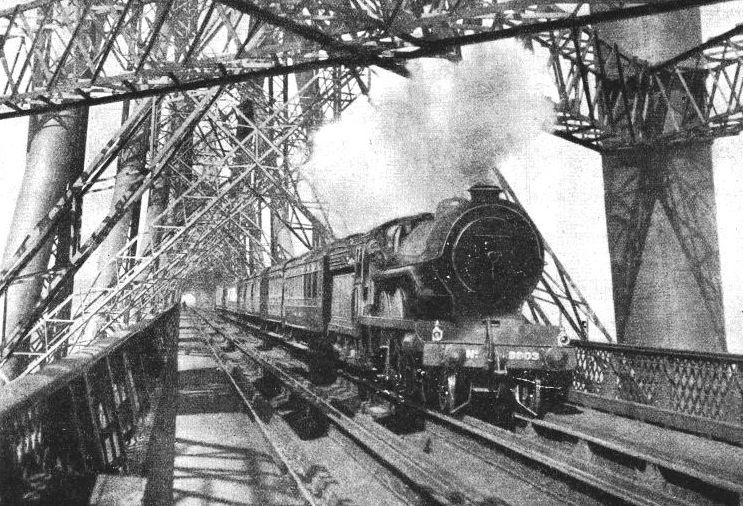

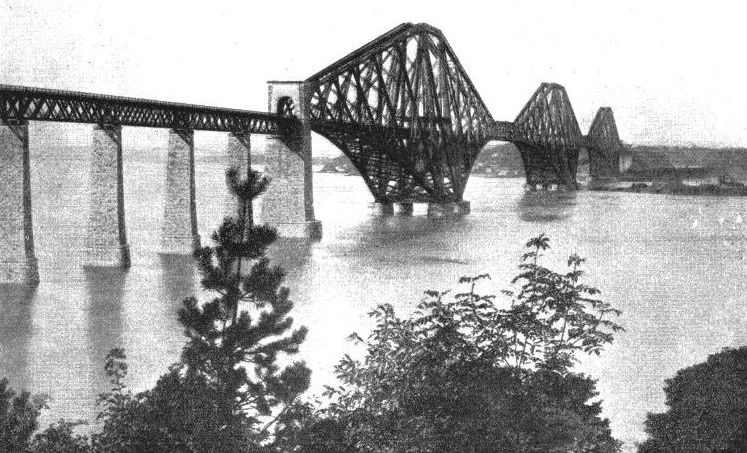

ACROSS THE FIRTH OF FORTH -

Possibly not many travellers in the north-

Less than fifty miles farther north, too, may be seen an ivy-

As the “Flying Scotsman” travels still farther north, however, another example can be seen of the “Stephenson touch” in the railway crossing into Scotland over the Royal Border Bridge, designed by Robert, son of George Stephenson. The bridge was opened by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1850. Its twenty-

91 ft above water level, for a length of 720 yards. After crossing the border into Scotland the train runs over the historic North British Railway line, famous for two of the most notable triumphs of bridge building -

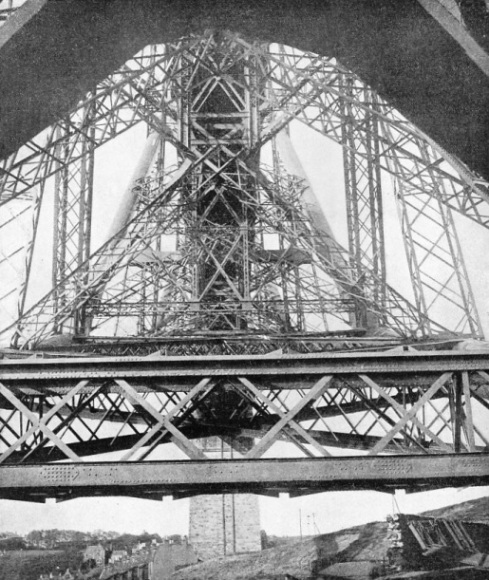

Enormous public interest was aroused by these ambitious engineering projects, especially as the Forth Bridge had the largest cantilever spans in the world. There are twenty-

The Stimulus of Rivalry

Such an enormous outlay in those days shows clearly that the engineering of our main line routes was imaginatively conceived and boldly executed. The great markets and centres of population had much to gain from quick and safe intercommunication, and their needs were at once an incentive and a reward to the railway builders.

A spectacular race for records occurred in 1888, when the London and North Western sought to steal a march on its competitors by reducing the time taken between Edinburgh and London to eight and a half hours. The Great Northern brought their time down to seven and three-

This spirited rivalry might have gone even further, but there was a public feeling against a struggle to save seconds, and it was found that the “race trains” were being avoided, except perhaps by the sporting fraternity who could not resist the thrill of speed. So finally both companies decided to abandon the struggle.

In our modern system of grouped railways, the whole country is now served by four great undertakings in which are incorporated, for the common good, the bitter rivals of bygone days. But the recalling of those separate entities and the recounting of some of their struggles have served to show that their development was from the first a vigorous growth -

Hope, courage, invention, and endeavour -

THE BRIDGE THAT COST £3,500,000. The great Forth Bridge, carrying the railway from Edinburgh to the North, forms one of the most vital links on the route of the “Flying Scotsman”. The structure is 1½ miles long, and each cantilever towers 361 ft above water level.

A STEEL NETWORK IN THE SKY. This unusual view of the Forth Bridge, taken from below the railway tracks, gives a graphic impression of the wonderful structure.

You can read more on “The Flying Scotsman”, “The Forth Bridge” and

“The Romance of the LNER” on this website.