An All-Pullman Journey from London to the Heart of Switzerland

FAMOUS TRAINS - 46

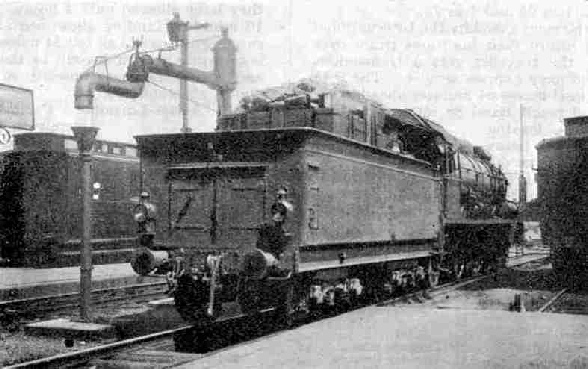

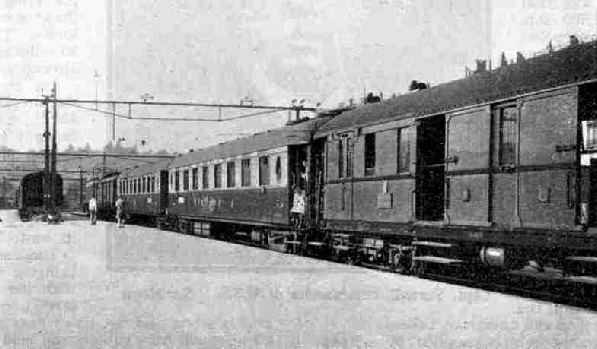

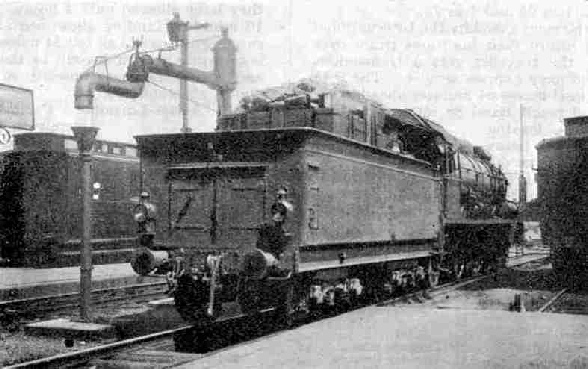

The “Edelweiss Pullman” at Luxembourg. It is headed by one of the monster 4-cylinder “Pacifics” of the Belgian National Railways, and about to begin the non-stop journey of 102½ miles through the Ardennes to Namur.

IT has been my good fortune during the past summer to “discover” a new gateway to the Alps. I had tried most of the best-known routes before and knew them by heart, so to speak; but the L.N.E.R, and the International Sleeping Car Company jointly introduced me to what turned out to be the most delightful journey I have ever yet made to and from Switzerland. It is no new route; neither is it the shortest, nor the most direct, nor the quickest. It was not, indeed, until the International Sleeping Car Company had added yet another strand to the web of their luxurious Pullman car expresses that now connects all parts of Western Europe that one would have thought seriously of this “way in” to Switzerland.

The “Edelweiss Pullman” now makes possible an “all-Pullman” journey from London to the heart of the Alps and, what is more, the only such all-Pullman journey to and from Switzerland that can be made - a fact that the L.N.E.R. seem a little slow to advertise. There is, of course, the short break across the North Sea, but there a cosy berth in a comfortable cabin of one of the miniature liners with which the L.N.E.R. spans the Channel crossing is the best of all possible substitutes for a Pullman armchair.

Let me now be a little more explicit. My journey was made, first from Liverpool Street Station in London to Parkeston Quay, Harwich, and thence across to Antwerp in Belgium. The “Eidelweiss Pullman” runs every day between Amsterdam in Holland and, during the height of the summer season, Lucerne and Zurich in Switzerland, the train being divided at Basel in order that one half may go to the former town and the other half to the latter. The route is right down through Belgium and the little Duchy of Luxembourg, and then on through Lorraine and Alsace - passing en route the historic cities of Metz and Strasbourg - to Basel. On arrival in the steamer at Antwerp you can either taxi across to the Berehem Station, where the “Edelweiss Pullman” stops on its way from Amsterdam, or you can take the boat train for the short journey direct from Antwerp Quay into Brussels, and join the “Pullman” at the great North Station in the Belgian capital.

There are some who prefer the rival attractions of the German “Rheingold Express” to those of the “Edelweiss Pullman" when entering Switzerland from this direction. But the “Rheingold” journey, with its fine scenic route up the Rhine from Cologne, means leaving Liverpool Street 15 minutes earlier, by the Hook Continental; crossing from Parkeston Quay to the Hook of Holland; starting to get dressed soon after five o’clock in the morning and, what is more, while the ship is still on the open sea - which you might not relish overmuch - even if you are, like me, a very hardened traveller!

As compared with this, the Antwerp boat allows you to sleep until you are cruising peacefully up the quiet waters of the River Scheldt. Then, at your leisure, you get up at about seven o’clock, take a turn round the deck in the morning sun, have your last good English breakfast down in the dining saloon, and are ready to make an unhurried landing, feeling in the “pink” of condition to enjoy a new day, at 8.30. If you intend to intercept the “Edelweiss Pullman” in Antwerp, indeed, you need not be up as early as this, as she is not due to leave Berehem Station till 10.9 a.m. If you are going into Brussels by the boat train, however, you must be in your place by 8.52 a.m, when the train leaves Antwerp Quay. Even this is a couple of hours later than the departure from the Hook of Holland of the “Rheingold Express”, of which we are to make the acquaintance, much later in the clay, at Basel; for from Basel to Zurich, and also from Basel to Lucerne, the severed halves of the two famous expresses keep each other company. There is one other advantage of the “Edelweiss” route - it is the cheaper of the two!

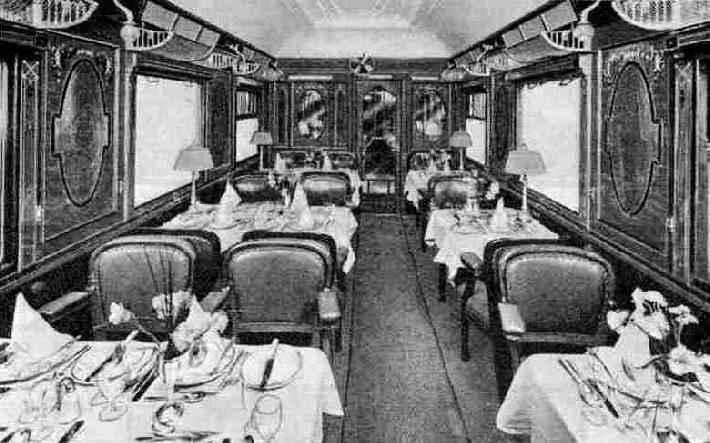

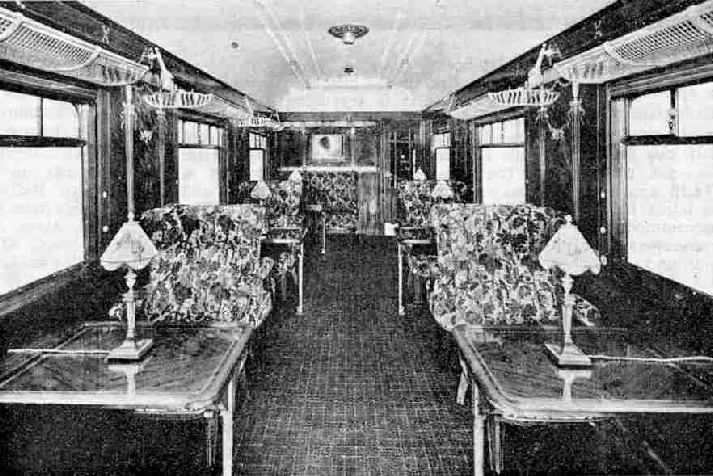

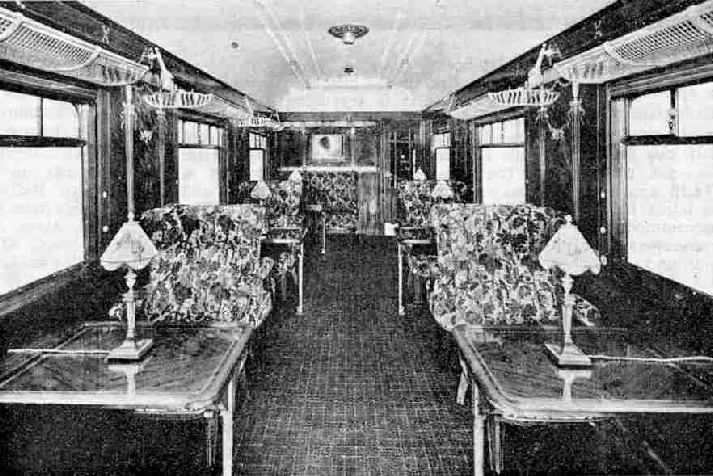

Interior of one of the cars on the “Edelweiss Pullman”. The photograph gives an excellent idea of the spaciousness and beautiful decoration of these cars, which were built in England.

So it was that on an evening early in July I found myself on No. 7 platform at Liverpool Street terminus, boarding the “Antwerp Continental”. The Pullman Car Company are well represented on this train, as in addition to the ordinary first-class “armchair” Pullman car, the ordinary restaurant car catering is now done in a handsome three-car Pullman “set”. This is the first time that the Pullman people have introduced in England any Pullman restaurant cars of this type, without a supplementary charge for seats; although such cars have been run in Scotland for a long time past on the Caledonian Section of the L.M.S. The remainder of the train is made up of the fine bow-ended standard corridor stock of the L.N.E.R., with automatic couplings, the whole nine or ten vehicles making a particularly handsome turn-out.

I must not dwell at length on the journey to Parkeston Quay, however, as this was but the introduction to our real subject matter. Suffice it to say that on my trip the “Hook Continental” went out ahead of us at 8.15 p.m, with one of the new 3-cylinder 4-6-0 “Sandringham” class engines and an enormous train of 14 cars, which included three restaurant cars and two Pullmans, weighing all but 500 tons behind the tender. The extra five minutes now allowed to Parkeston by this express are well deserved with such loads as this.

We had a train of 315 tons only, with one of the familiar Great Eastern type 4-6-0 engines - No. 8580 of the last series, fitted with Lentz valves - and the driver early was determined to show that the 82-minute schedule over the 69 miles to Parkeston had no terrors for him! In fact we passed Shenfield in a time I have never previously equalled - 27¼ minutes for the 20¼ miles, including the slow exit to Stratford and the formidable climb up Brentwood Bank. Then, after touching over 70 miles an hour and getting through Chelmsford in 36 min. 20 sec., we had positively to “ease” in order not to overtake the Hook train. Even so we ran the 39¼ miles from Shenfield to Manningtree in 41¾ minutes, and would have been at rest at Parkeston Quay in 81 minutes from Liverpool Street but for being pulled up at the home signals to allow the “Hook Continental” to clear the platform ahead of us.

Of the journey across the North Sea also little need be said. You may be mystified to notice that the bows of the boats - first the Hook boat, then the Antwerp boat, and then, in the height of summer, the Zeebrugge boat - are all pointing up the Stour estuary as they lie alongside the quay. They start in the same order, at intervals of a few minutes, and it is a fine sight to see the three brilliantly-lighted ships, first steaming in a semicircle away from the quay, one after another, and then heading in a stately procession seaward, line ahead, through a mazy succession of lighted buoys.

After that you go down below, as it is now well after 10 o’clock, and turn in for a comfortable sleep of eight hours or so. The motion of the boat is so perfectly steady that, unless it is very rough, you will know nothing of some six hours of open sea, but will wake up in the long reaches of another wide river - the Scheldt. It is nearly eight o’clock when the miles and miles of quayside come into view which, with the dignified background of the cathedral, proclaim the port of Antwerp. Soon after eight o’clock you have made a leisurely disembarkation.

The stock of the boat train provided by the Belgian National Railway Company from Antwerp Quay into Brussels, consisting mostly of rather primitive six-wheelers, is, it must be confessed, a poor exchange for the luxury of either the “Antwerp Continental” or the “Edelweiss Pullman”. The short journey, with its one intermediate stop at Malines, is soon over, however, and at 9.53 a.m. we find ourselves in the great Nord Station at Brussels. Further, we have always the option of getting the “Edelweiss” at Berehem, but the railway enthusiast prefers to take the opportunity of nearly an hour’s inspection of Belgian locomotives and rolling stock at Brussels before the “Edelweiss” goes south at 10.49 a.m.

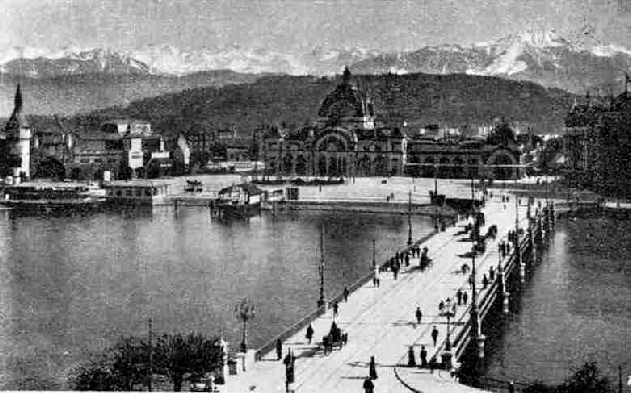

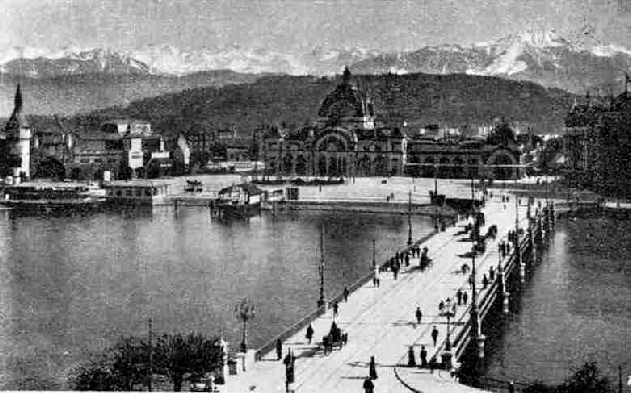

View of Lucerne. The handsome railway station is seen In the centre of the photograph, and in the distance tower the snow-clad Alps.

There is much to be seen, too. The most intensive service of express trains in Belgium is that which works between the cities of Brussels and Antwerp. Known as the “Trains Blocs”. because they are composed of special centre-corridor sets of coaches, with clerestory roofs, these expresses run at frequent intervals throughout the day, taking 36 minutes for the non-stop journey of 21¼ miles, or 42 minutes if a stop at Malines be included. For the most part they are worked by big ex-German 4-6-0 four-cylinder compound engines taken over from the Prussian State Railways after the war, many of which, together with “Atlantics” and 4-4-0’s, are seen in and about the station. De Glehn compound Belgian 4-6 0’s, of a neat type with brass-capped chimneys, are also seen in large numbers, together with inside-cylinder 4-4-0 engines modelled on the “Dunalastair” type of the late Caledonian Railway. The earliest of the Belgian engines last-mentioned were actually built in Scotland.

At twenty minutes to eleven the blue and white cars of the “Edelweiss Pullman” are seen approaching from Schaerbeek. They have already been 3½ hours on the journey, having left Amsterdam at 7.25 a.m. (Dutch time, which is 20 minutes in advance of the ordinary Western Europe time), and called at The Hague and Rotterdam before reaching Rosendaal, where the Netherlands Railway authorities of Holland hand the train over to the Belgians and the first frontier is crossed. The length of journey in Holland is 89 miles in all, and with 54 miles through the north of Belgium, including the intermediate stop at Berehem, the “Edelweiss Pullman” is brought into Brussels (Nord) at 10.41 a.m. Immediately in front of it from Antwerp, but running round Brussels into the Midi Station and from there non-stop over the 192½ miles to Paris - the longest non-stop run on the mainland of Europe - is the “Oiseau Bleu” another all-Pullman express.

In all probability the “Edelweiss Pullman” has been brought from Rosendaal to Brussels by an ex-German 4-6-0, but at the Nord Station, which is terminal, the train is reversed. Waiting to take it southward through Belgium to Luxembourg is one of the most singular-looking “Pacific” engines to be seen in any part of Europe. They are known as “Type 10” of the Belgian National Railways.

The strange feature of these “Pacifics”, the earliest of which appeared as far back as 1910, is that a comparatively short boiler is used, with a sharply tapered barrel; and that the smokebox of the engine finished well clear of the cylinders and the bogie, which project like a great ram in front. Four high-pressure cylinders are used, so that the locomotives are simple and not compound; and the steam from each pair of cylinders is exhausted in the rebuilt engines into two separate chimneys, which are covered with one long casing, surmounted by a deep brass cap, and a high “capuchon” or smoke deflector on top of that.

The whole appearance is one of extraordinary power, but the Belgian “Pacifics” appear at times to have some difficulty in living up to the reputation that they might well earn by their massive outline. Their work has been greatly improved, however, since they have been rebuilt and modified in various respects, from 1922 onward. It must not be forgotten also, that the fuel used is of poor quality as compared with that to which we are accustomed in this country, and that the gradients over which we are to pass between Brussels and Luxembourg are extremely severe, including many miles inclined at between 1 in 60 and 1 in 70.

In exchange for the small supplement asked by the International Sleeping Car Company for the use of their luxurious train, over and above the ordinary fare, the traveller gets a tremendous advantage in time over the ordinary express service. The 9.45 a.m. express from Brussels to Basel leaves 64 minutes ahead of us, but we pass it on the way and reach Basel 85 minutes sooner. Even the best ordinary express, leaving Brussels at 12.40 p.m, takes two hours longer on its journey to Basel than we do. The Pullman train is not heavy, the formation consisting of one “ fourgon” or luggage-van; one second-class car and one first-class car for Lucerne, and three similar vehicles for Zurich, making a total of six cars, or about 250 tons empty. With passengers and luggage 255 to 260 tons would represent the total weight behind the tender.

Changing engines at Strasbourg. The Alsace-Lorraine “Pacific” with high-capacity 8-wheeled tender, is backing down for the run of 98½ miles non-stop to Metz. Over this stretch average speeds of more than 60 miles an hour are maintained continuously.

Out of Brussels our train has to make a wide circuit round the eastern suburbs of the city, passing on the way the important Quartier Leopold Station, which this is one of the few trains of the day to give the “go-by”. Then follow heavily-rising grades and sharp tips-and-downs on the way to Namur, which is heralded by a very abrupt descent to the valley of the Meuse. For the stage of 38½ miles from Brussels to Namur the timetable allows 54 minutes, and over such a route the maintenance of an average speed of even 43 miles an hour is none too easy. At Namur we see a number of engines of distinctly French appearance. These are the property of the Nord-Belge Company, closely allied with the French Nord line, and are responsible for working the route from the French frontier through Namur and Liege to the German frontier, which is the main line from Paris to Berlin.

After Namur heavy climbing begins again, out of the Meuse Valley up to the high ground of the Belgian Ardennes, the worst ascent being for eight miles continuously at 1 in 62½. The run on which we are now engaged is the longest non-stop break made exclusively on Belgian territory, and is also the longest non-stop journey made by the “Edelweiss Pullman” over the 102½ miles from Namur to Luxembourg. There is a liberal time allowance of 145 minutes, but this has to cover, in addition to the heavy grading, a number of severe slacks over curves intermediately.

In the heart of the Ardennes district we pass Jemelle - an important locomotive centre, where we shall see an extensive collection of engines, including the big 2-10-0 type, similar in general design to the “Pacifics” which is responsible for working freight over this heavy route - and Arlon, the southernmost important town in Belgium. At Kleinbettingen we cross the Belgian frontier, and at 2.12 in the afternoon we come to rest at Luxembourg, the capital of the little independent Duchy of that name. Although this is a “through” station, we have entered the city from the south side, and so for the second time must reverse our direction of running in leaving for Metz. The locomotive of the Alsace-Lorraine Railways, which is to take us over from the Belgian “Pacific”, is therefore waiting outside the station as we enter.

Two hundred and eighty-four miles of the journey have now gone by, and have occupied just over seven hours; an overall average of almost exactly 40 miles an hour. The French are going to raise the figure considerably, however. For their 225 miles from Luxembourg to Basel, notwithstanding four stops, they have allowed only 4 hours, 21 minutes; and deducting the 10 minutes standing allowance at these four points, you have a running average of all but 54 miles an hour. The lie of the country is certainly in their favour, as the line is fairly level throughout; and from Strasbourg onward, in the wide valley of the Rhine, almost absolutely so.

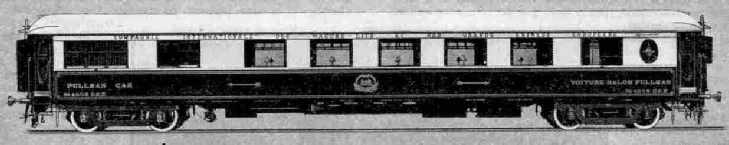

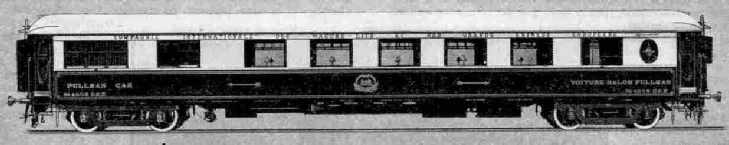

A typical modern Continental Pullman Car used on the “Edelweiss Pullman”.

The Alsace-Lorraine “Pacifics” do not confine themselves merely to keeping time, however. On the day of my journey our Belgian “Pacific” unfortunately failed at Brussels. It was half-an-hour before a substitute 4-6-0 was found, and what with this insufficient power over the heavy Belgian gradients, and an interminable succession of severe track relaying slacks, we were handed over to the French 70 minutes late at Luxembourg. Yet so splendid was the running, both in France and Switzerland, that, with the assistance of a considerable curtailment of the booked stopping time at Basel, we recovered 40 minutes of the loss and were only half-an-hour late at Zurich. The best piece of running on the Alsace-Lorraine line was from Metz to Strasbourg, this stretch of 98½ miles, allowed 107 minutes, being covered in 96 minutes, start-to-stop.

In the opposite direction, on my return journey, an Alsace-Lorraine 4-6-0 ran us from Mulhouse to Strasbourg, 67½ miles, in 69 min. 50 sec., and on from Strasbourg to Metz, uphill in the early stages, a “Pacific” covered the 98½ miles in 107 min. 50 sec., though the respective time allowances are 73 and 112 minutes. On the first stage we ran a stretch of 59 miles from Bolwiller to Grafenstaden in 56¾ min., and on the second, despite a bad service slack, the 84¼ miles from Vendenheim to Courcelles were reeled off in 88 min. 20 seconds. This is fine travelling, over a line whose speed exploits are not so much in the public eye as those, say of the Chemin de Fer du Nord.

The Luxembourg frontier is crossed between Luxembourg and Thionville and, to save any disturbance of passengers, French customs and passport officials make their visits inside the train. The succession of frontier crossings on this journey raises other complications also. As we enter every fresh country you will see the Pullman car attendants pass rapidly through the train, collecting all the cards showing the refreshment tariff and substituting fresh ones. So, at Thionville, we change over from prices in Belgian francs to those in French francs. Had I been a little more wideawake I should have realised that my afternoon tea would cost more on French soil than on Belgian, and acted accordingly! On this particular trip of mine the problem of exchange was really acute, and at one time I had seven different “currencies” in my pocket, of the six European countries I visited, in addition to British, But that is another story.

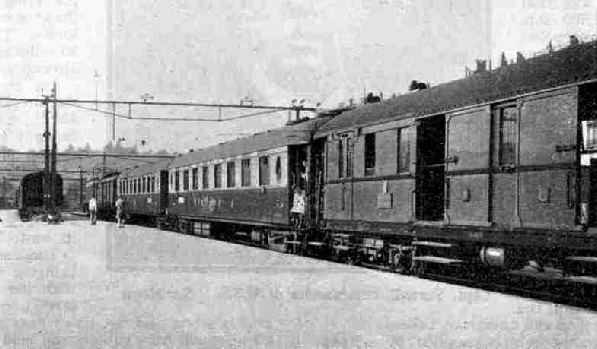

The “Edelweiss Pullman” leaving Lucerne for Basel, Swiss Federal Railways. The overhead equipment is for alternating current at 13,000 volts. In the foreground is the brake-van of the “Rheingold Express” portion.

The 20¼ miles from Luxembourg to Thionville are allowed 26 minutes which, because of certain slacks en route is a very tight time and may not be quite kept. After a halt of one minute at Thionville, where the customs and passport officials alight, we enter part of the iron and steel producing country that occupies the adjacent areas in the south of Luxembourg, the east of France and the west of Germany. Vast resources of iron ore in the neighbouring hills have established this great industry, and we pass row after row of blast-furnaces, all with the most modern equipment; as well as steel-plants and rolling mills, culminating in the extensive and well-known Hagondange works. Shortly afterward we are passing over elaborately fenced bridges into the fortified city of Metz, with the cathedral a prominent object on the right of the train.

It is 18¼ miles from Thionville to Metz, and a brief 20 minutes for this again proves to be an extremely tight schedule. But we have the 98½-mile run to Strasbourg ahead now, and with a capacity for running for many miles indefinitely at over 60 miles an hour, our “Pacific” will easily regain any lost minutes.

We shall not fail to notice, by the way, that since we left Luxembourg we have changed over to the opposite track. That is to say, instead of passing trains travelling in the other direction on our right, they are now on our left-hand, as is the custom on the railways of Alsace-Lorraine and in certain other parts of Europe. We hurry on southeastward through Benestroff, and then slow over a sharp curve at Rieding, where we join the main line from Paris to Strasbourg through Nancy, noticing here a nest of sidings filled with old locomotives awaiting the melancholy fate of “scrapping”.

Next follows a tunnel of nearly a mile in length, ushering us into a deep valley through which the railway runs amid very fine scenery, for the best part of 15 miles, passing through a number of short tunnels. We are here threading the northernmost spurs of the Vosges Mountains and are travelling due east. We emerge into open country again at Saverne, presently bearing round until we are heading full south; and some 25 miles later the outskirts of Strasbourg bear into view. We are due to spend five minutes at this historic city, from 4.54 to 4.59 p.m., and here engines are changed. We may have the services of another “Pacific”, or possibly of a 4-6-0 locomotive. In either case it is certain to be a four-cylinder compound engine.

For the next 67½ miles to Mulhouse the allowance is only 71 minutes, but the almost perfectly fiat grading of the track, as well as its splendidly straight lay-out, allows of the timing being maintained without difficulty. High hills may now be seen rising at a distance on both sides of the broad Rhine Valley, up which we are now hurrying. Far away to the east are the mountains of the Black Forest in Germany, on the other side of the river. To the west, prominently in view after Selestat, we see the Vosges, picturesquely crowned with a whole succession of castles in lofty positions, and culminating in the Grand Belchen, whose summit is 4,670 ft. above the sea. At Mulhouse we are joined on the east by the Belfort main line, direct from Calais and Paris, over which we travelled in the darkness when coming to Switzerland by the “Engadine Express”.

The last short stage to the French frontier lies ahead. For the final 20½ miles to Basel, with a tortuous finish from St Louis into the great Hauptbahnhof, or Central Station, we are allowed 27 minutes; and at 6,38 p.m. we should be on Swiss territory.

The “Edelweiss Express” has now left 509 miles of journey behind her, over which 11 hours, 33 minutes have been spent; and a brief wait is now in prospect - of 19 minutes for the Lucerne portion and of 32 minutes for that to Zurich - during which customs and passport formalities will again be carried out. Meantime the “Rheingold Express” which reached the Baden Railway Station in Germany on the other side of the river six minutes ago, appears at the opposite end of the Hauptbahnhof at 6.48 p.m, 10 minutes after us, in charge of a German 4-6-0 locomotive. All resplendent in violet and cream, with broad gold lining, the “Rheingold” cars of the German Mitropa Company present a striking contrast to the royal blue and white of our Pullmans.

The “Rheingold Express” is a bigger train than the “Edelweiss Express”, as it includes not only the through portions from the Hook of Holland to Zurich and Lucerne, but also a couple of through cars from Amsterdam to Lucerne, which left the Dutch city eight minutes after our express this morning, and were attached to the main “Rheingold Express” at Utrecht. A considerable amount of sorting of both the famous trains now takes place, with the result that a train of nine cars is made up for Lucerne - brake, three “Rheingold” cars from Hook of Holland and two from Amsterdam, and then our two “Edelweiss” cars and the “Edelweiss” brake, a heavy formation of roughly 400 tons. This leaves for Lucerne at 6.57 p.m., and the Zurich train, with two “Edelweiss” and two “Rheingold” cars, and also two brakes, at 7.10 p.m.

We have been over both the Swiss routes previously, and have made the acquaintance of the Swiss electric locomotives, as well as of their remarkable tractive powers. From Basel to Lucerne we travelled with the “St Gotthard Pullman” which, by the way, is due in Lucerne just an hour after our arrival.

On the way to Lucerne we thread the 5 miles of the Hauenstein Tunnel under the Jura Mountains, and reach Olten, 24½ miles, in 33 minutes; while the final 35¼ miles to the famous lakeside resort are scheduled to be covered in 49 minutes. This portion of the “Edelweiss. Pullman” finishes its journey of 569 miles, and its transit of four countries and a duchy, 13 hours, 18 minutes after starting from Amsterdam. The Zurich portion has a nonstop run over the route that we traversed with the “Engadine Express”, reaching the great industrial centre of Switzerland seven minutes later, at 8.30 p.m; 80 minutes being allowed for the distance of 55 miles.

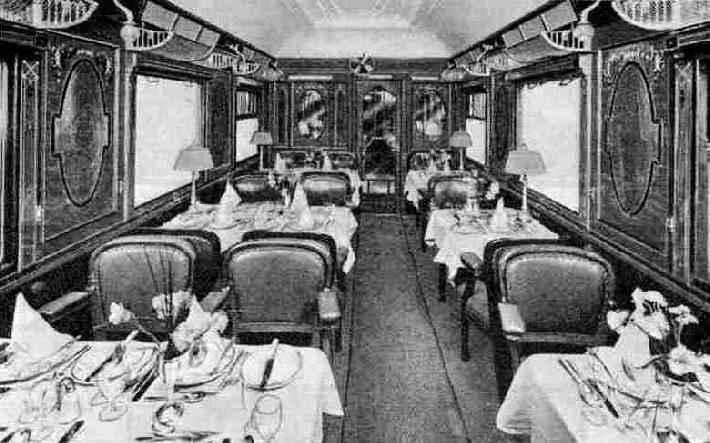

Interior of a typical modern Continental Saloon Pullman Car.

You can read more about “The Engadine Express”, “The Glacier Express”, “International Sleeping Cars” and “Through the Bernese Alps” on this website.