The Most Concentrated System in the World

RAILWAYS OF EUROPE - 10

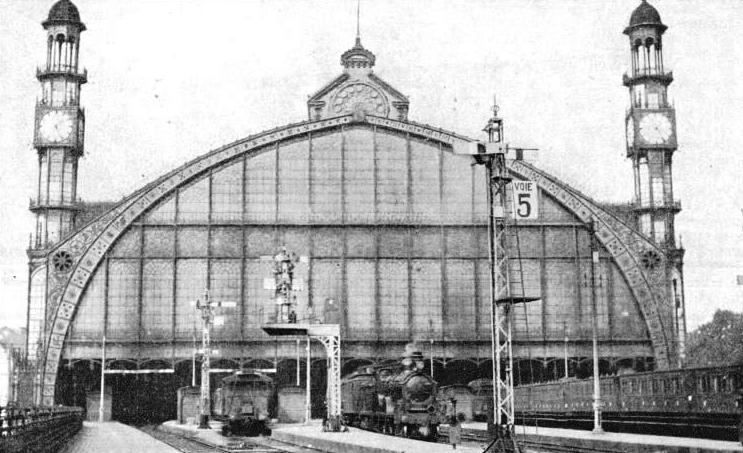

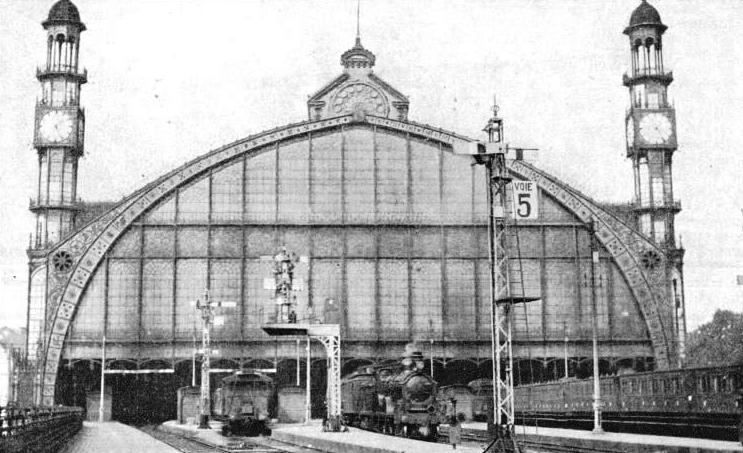

THE TERMINUS AT ANTWERP, an important station on the Belgian National system. One of the four half-rose windows of the cupola is seen in this illustration.

SOME readers may be surprised to learn that the densest railway system in the world belongs to Belgium. Their surprise will, however, be tempered by the information that Belgium, after the Principality of Monaco, is the most densely populated country in Europe. According to the latest available census figures, the density per square mile is 702. Next on the list come Holland, with 627, and Great Britain and Northern Ireland, with 468 inhabitants to the square mile.

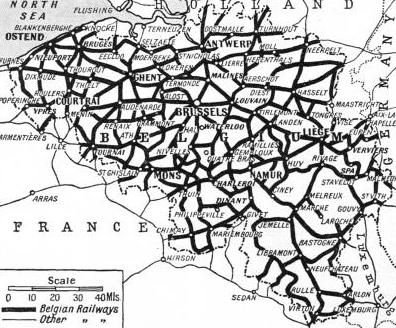

But, although Belgium is not much, more thickly populated than Holland, her railway mileage is far greater. The total area of Belgium is 11,755 square miles, as compared with the 12,603 square miles of Holland. But, whereas Holland has 2,313 miles of railway route, the slightly smaller country of Belgium has no fewer than 6,893 miles. Great Britain, Germany, France, and the United States all have close railway networks in their industrial and metropolitan areas, but these are outweighed by great patches of territory in which railways are few and far between. In Great Britain the complex railway systems round London, Birmingham, Manchester, and Glasgow are balanced by such places as Central Wales and the vastnesses of the Scottish Highlands, where the population is small and railways are infrequent.

Belgium’s oldest main line is that between Brussels and Malines, opened on May 5, 1835. As in Germany, Belgium is celebrating her railway centenary as we write, but the Brussels-Malines line is eight months older than the Nuremberg-Fürth line in the larger country. It also possesses the distinction of having been the first steam passenger line in Continental Europe, for horses formed the normal motive power of such lines as the Budweis-Kerschbaum Railway in Austria and the Lyons-St. Etienne Railway in France. The three original locomotives, all built in England, were “L’Elephant”, a 2-4-0 with double frames, built by Tayleur & Co, and “Stephenson” and “La Fleche” (“The Arrow”), both of the 2-2-2 type, built by Robert Stephenson & Co, at Newcastle-on-Tyne. All three locomotives were attached to the inaugural train, which consisted of thirty carriages, accommodating about 1,000 passengers. On the return journey, “L’Elephant” took the train single-handed.

A year after its opening, almost to the day, the Brussels-Malines Railway was extended to Antwerp, thus bringing the capital into direct communication with the ocean shipping lines, independent of canal traffic. This line is now part of the direct route from Paris to Amsterdam via Esschen and Rosendaal, over which the fine “North Star” Pullman express runs daily in either direction, together with the equally famous “Edelweiss Express”, connecting Holland with Switzerland.

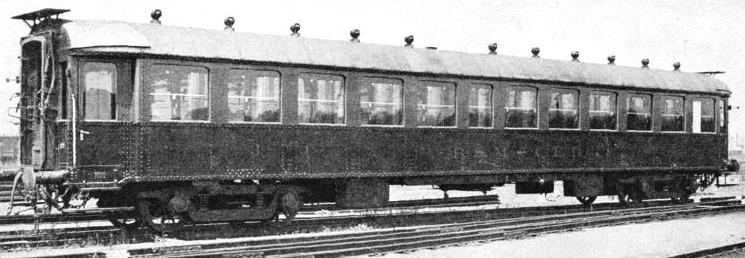

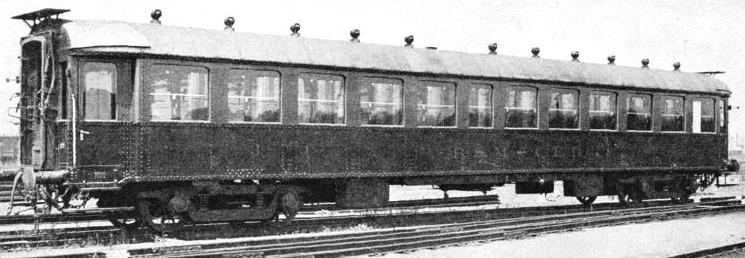

ALL-STEEL COACHES in Belgium are steadily replacing old rolling stock both for local and international lines. The photograph above shows a new third-class corridor coach.

By the end of 1843 the Belgian Government had extended the railway system to Ghent and Ostend, to the German frontier via Louvain and Liège, to the French frontier via Mons, from Ghent to Courtrai, and from Braine-le-Compte to Namur. The whole Belgian State system extended rapidly. In 1851 the Liege-Namur Railway was opened by an English company, using Crampton type locomotives built by Tulk and Ley. This line eventually passed over to the control of the Northern Railways of France, though the English company received a substantial rent for it. To this day the Nord-Belge still forms an important section of the French Northern Railway. The Belgian State Railways, on the other hand, have been handed over to the Belgian National Railways Company within recent years. Thus Belgium, as well as her neighbour Holland, has now no true Government railways.

Many people receive their first, and perhaps only experience of the Belgian National Railways in the course of the boat train journey from Ostend to Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle) in Germany, via the frontier station at Herbesthal. On the outward journey most of this run is made during the night, but in the return direction, with the train running in connexion with the afternoon boat from Ostend to Dover, the traveller can gain quite a good superficial idea of the Belgian railways. Travelling westwards, the country is at first reminiscent of Derbyshire, intense industrial activity alternating with the semi-mountainous limestone crags rising above the Maas valley, among which King Albert met with his tragic death in February, 1934. This country is impressive, but the passenger seldom feels remote from the whirl of modern industrial activity.

At Liège, or Luik as it is called in Flemish, we find one of the most important railway and industrial centres in the country. A railway map of the Liège district resembles a drawing of a huge, half-finished spider’s web, with the Guillemins Station in the middle and the spider’s “parlour” in the Tongres loop line, to the north.

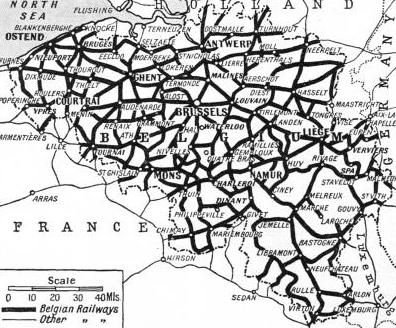

NEARLY 191,000,000 PASSENGERS are carried yearly over the 6,893 miles of track in Belgium. The map above shows the network of lines in that country, which has the greatest mileage of rail per square mile in the world.

The main line from North Germany has come in from the east through Pepinster, being joined just outside by the line bringing in traffic from Luxem-burg and the southern frontier of Belgium, together with an alternative route, used by local trains, from Aachen via Montzen. From the south-west comes the line of the Nord-Belge Railway from Namur, Dinant, and Paris. The Nord-Belge has a by-pass or avoiding line, which runs round Liège proper and links up with the Belgian National line to Visé and Maastricht in the extreme south of the Nether-lands. Near Maastricht, incidentally, at the frontier station at Eysden, the ex-German Emperor was kept waiting all night in 1918 while the Queen and Government of the Netherlands decided whether they could allow him to take refuge in their country.

The main line westwards out of Liège climbs upwards from the city on a long and severe incline of 1 in 33 - a giant version of that by which the LNER leaves Glasgow. From 1842, when it was built, to 1871, trains were hauled up this bank by stationary engines and cables, but now they are assisted in the rear by powerful banking engines. These will be detailed later. At Landen an important main line diverges and runs south-west through historic Ramillies to the great industrial area round Charleroi, while lesser lines strike off to Statte and St. Trond.

Another junction is passed at Tirlemont before Louvain is reached. After Liège, this is the most important place we have seen so far. The main east-to-west line is here joined by another connecting line from the southern industrial area. At the north end the main line splits into three, one section running to Aerschot, the second to Malines and Antwerp, and the third forming the continuation of the main line to Brussels and the west. A line now projected will link up Louvain with Drieslinter, at present reached by a double track branch from Tirlemont.

Brussels is the centre of the Belgian National Railways system from a territorial as well as from an administrative point of view. There are three termini, the North Station, the South (Midi) Station, and the great goods station at Allée Verte. The last named was originally the main passenger station. To the north of the Allée Verte and North stations, between Schaerbeek and Laeken, is a complicated diamond-shaped junction, with a through line passing across it from north-east to south-west. To the north-east of this is a still more complex junction, governing the divergence of the main lines to Louvain, whence our imaginary traveller has come, to Malines and Antwerp, and to Ghent, Bruges, and Ostend. A connecting line runs round the city to the South Station, whence there is another line running out to Ostend, joining that already mentioned near Denderleeuw.

Belgium’s “Black Country”

From the South Station a second line runs southwards to Hal, where it diverges, one route bearing round to Tournai and eventually to Lille and Calais, while the other goes straight down to Mons, for Paris. The third main line from this terminus runs south-east via Namur, where it crosses the Nord-Belge main line, to Arlon, for Luxemburg, Metz, Strasbourg and Basle. A new connecting line between the North and South stations at Brussels, with a Central Station between them, will greatly facilitate the handling at the Belgian capital of through railway traffic, which is very heavy.

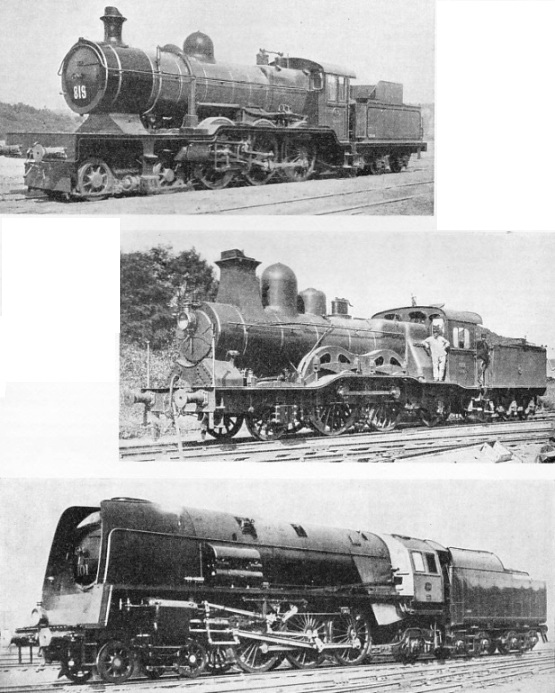

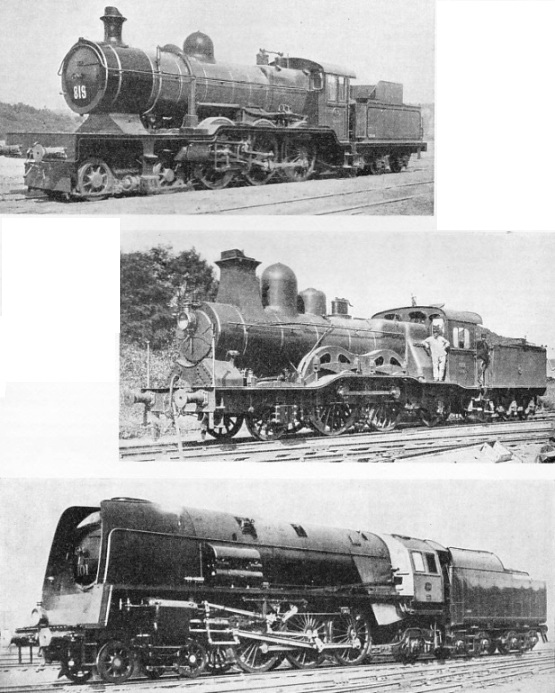

AN EXPRESS PASSENGER LOCOMOTIVE, type “8”, with the 4-6-0 wheel arrangement. This locomotive is a compound with two high-pressure outside cylinders. The high “capuchon” in front of the chimney is a feature of many Belgian engines; it is fitted for smoke deflection purposes. Note should also be taken of the prominent way in which the engine number is displayed on the smokebox door. This type of engine is being superseded by more powerful types.

AN EXPRESS PASSENGER LOCOMOTIVE, type “8”, with the 4-6-0 wheel arrangement. This locomotive is a compound with two high-pressure outside cylinders. The high “capuchon” in front of the chimney is a feature of many Belgian engines; it is fitted for smoke deflection purposes. Note should also be taken of the prominent way in which the engine number is displayed on the smokebox door. This type of engine is being superseded by more powerful types.

ONE OF THE “SOUVENIRS” - the name given to old 2-4-2 locomotives of this class by British soldiers during the war. The square chimney was formerly a common feature of some Belgian locomotives.

A MODERN “PACIFIC” locomotive operating on the Belgian National Railways. The engine was built in 1935, and, except for its wheel arrangement, closely resembles the LNER “Cock o’ the North” type. There are fifteen of these four-cylinder engines, each weighing with tender about 200 tons. The couple wheels have a diameter of 6 ft 5¼ in.

But the complexity of the railway lines round Charleroi puts those of Brussels and Liège completely in the shade. It is beyond the power of words to describe, and an idea of its almost labyrinthine lay-out can be grasped only by a study of the spot. Charleroi is in the heart of Belgium’s “Black Country”; it might well be described as the Belgian Birmingham. In addition to the many lines of the Belgian National Railways, a line of the Nord-Belge enters Charleroi from Lobbes and the French frontier at Jeumont.

Two important private railway systems now call for mention. One of these lies to the south of Charleroi; this is the Chimay Railway, running between Hastière, on the Nord-Belge line from Namur, to the French frontier just beyond Momignies, serving Mariembourg and Chimay on the way. The other is the Malines-Terneuzen Railway.

This is a curiosity, for about one-third of its system is not in Belgium at all, but in Holland. Moreover, that part of Holland which it serves, lying to the south of the mouth of the Scheldt, and containing the towns of Terneuzen, Sluiskil and Hulst, is completely cut off from communication with the main Netherlands Railways' system. There are, doubtless, Dutchmen and Dutchwomen living who have never seen a Dutch railway train, though they are familiar enough with the Belgian trains running on the Malines-Terneuzen Railway. This provides a parallel with the inhabitants of Port Ellen, on the island of Islay in Western Scotland, whose nearest railway station is Ballycastle in Ireland. A branch of the Malines-Terneuzen line runs south from Sluiskil to the frontier at Sas-de-Gand, whence a single line of the Belgian National Railways provides through communication with Ghent.

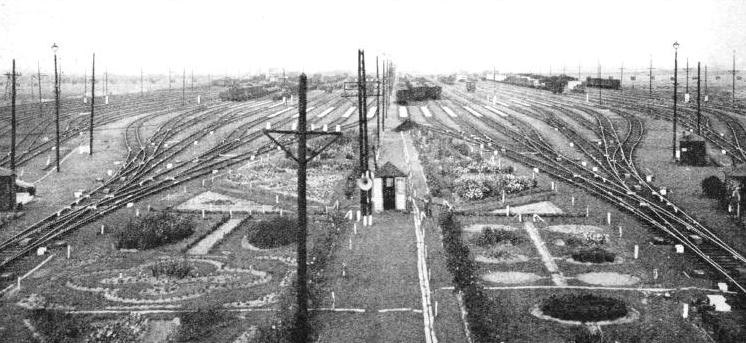

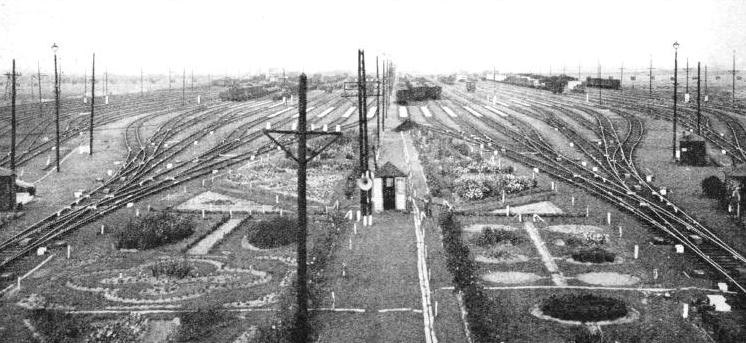

THE MARSHALLING YARD at Antwerp (Nord). The loud-speakers in the centre are for giving instructions to the men engaged in shunting operations. The flower-beds strike an unusual note in such large marshalling yards.

In the war of 1914-1918 the Germans relied principally on their own rolling-stock and portable equipment in the invaded territories of Belgium, but on those lines still under the control of the Allied forces there were all manner of locomotives, including, in addition to the Belgian engines, examples from the Great Western, the Midland, the Lancashire and Yorkshire, the North Eastern, the North British, the Caledonian, and other British lines. Brighton line tank engines worked into Poperinghe from Hazebrouck. These British engines were under the control of the Royal Engineers’ Railway Operating Division, which also used a number of Dutch engines, built in Manchester on the eve of the war and never delivered. Some of the American-built locomotives used by the Allied armies may still be seen on secondary work over the lines of the Belgian National Railways to-day.

For many decades the Belgian locomotive stock has had a decidedly cosmopolitan appearance. The old Belgian engines built by Cockerill and other firms for the Belgian State Railways in the latter part of the nineteenth century were fine and powerful machines, for their day, but in appearance they were almost grotesque. They had double frames, and, in many instances, square chimneys.

Wide Belpaire fireboxes and Walschaerts valve gear were usual, as these two features of modern practice both originated in Belgium. These peculiar-looking machines were nick-named “Souvenirs” by the British soldiers during the war. The more modern American-built engines, for some reason, were called “Spiders”. The old “Souvenirs”, in spite of their formidable appearance, were excellent workers, and some of them may still be seen. One of them was originally fitted, experimentally, with a treble-barrelled boiler; but this experiment was not repeated.

At the end of the last century a responsible Belgian engineer was much impressed by the work which Mr. J. F. Mclntosh’s famous “Dunalastair” class locomotives were doing in Scotland on what was then the Caledonian Railway. A number of exactly similar engines were ordered and set to work on the best Belgian express trains. They were so successful that, for more than a decade, all new Belgian State engines, passenger, goods, and tank, were designed very much on the lines of contemporary Scottish practice. Their neat outlines contrasted strangely with those of their square-chimneyed predecessors, and many of them survive.

Pioneer Locomotive Engineering

Belgium was a pioneer on the European continent in the use of very large locomotives, for both goods and passenger traffic. We have already mentioned the great incline which leads westwards out of Liège on the Brussels main line. Many years ago some twelve-wheeled Mallet compound tank engines were produced by Cockerill & Co. for working up this gradient of 1 in 33. Locomotives of this type weighed 105 tons in working order, and at the time of their introduction must have had few rivals in size and weight. To-day, ex-Prussian eight- and ten-coupled tank engines provide the banking engine power on the incline.

In the early years of the present century the Belgian lines tried the De Glehn compound 4-4-2 type of locomotive, which was then performing such spectacular feats on the Northern and Paris-Orleans Railways in France. This developed into a similar, though larger 4-6-0 type, examples of which may still be seen on some important express passenger trains. Then, just before the war, M. Flamme designed two very large types, a 4-6-2 for express passenger traffic and a 2-10-0 for goods traffic. The former were the heaviest “Pacifics” in Europe at the time of their introduction, weighing over 100 tons each without their tenders. They were ungainly engines, for the smoke-boxes were pitched far behind in the centre line of the bogie. Such of them as have survived the war have been rebuilt. They are now externally distinguished by double chimneys.

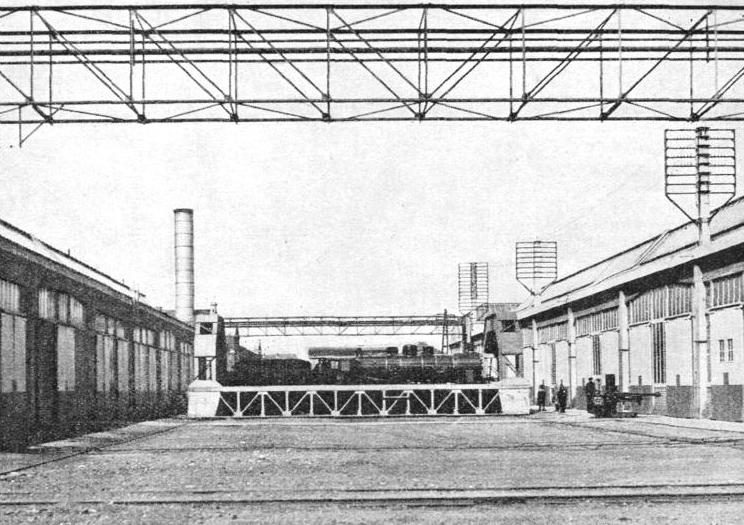

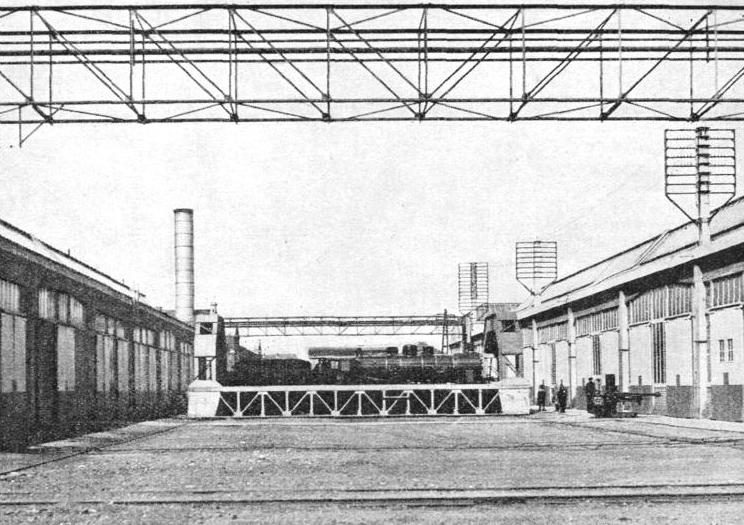

A GIANT TRAVERSER for locomotives at Malines. This is an ingenious device for moving engines from one track to another without the use of points. The railway between Malines and Brussels is the oldest main line in Belgium; it was opened in May, 1835.

The war put a stop to locomotive development in Belgium, just at a time when it was becoming interesting, but it had an unforeseen effect on the country’s locomotive stock in the postwar years. Since a great many Belgian locomotives and vehicles were destroyed or damaged beyond repair during the hostilities, part of Germany’s reparations to Belgium, as to France, took the form of locomotives, coaches, and wagons. The German locomotives were more modern and efficient than the majority of the Belgian survivors. One result of this influx of engines from Germany was a material increase in the country’s total locomotive stock. There were also the American-built War Department engines left behind by the British Army.

Among the German newcomers were representatives of practically every standard type of the former Prussian State Railways: “Atlantics”, eight-coupled goods engines, various tank engine classes, and hundreds of the well-known Prussian

4-6-0’s of Class P 8. There were also one or two “Pacifics” from Bavaria, but these were found unsuitable for Belgian requirements.

The ex-British War Department locomotives included 4-6-0’s (the “Spiders” already mentioned), and curious looking 2-6-2 saddle tanks. The latter are now employed on heavy shunting duties at Brussels, while the former may be found on secondary services in various parts of the country. In both instances their American parentage is at once obvious.

Within the past few years, under the sway of the Belgian National Railways Company, great strides have been made in the development of the country’s locomotive power. Among the new engines are some 2-8-2’s, which are claimed to be the heaviest passenger locomotives in Europe, the weight without tender being 128 tons. These were introduced in 1930, the first engine of the class attracting great attention and admiration at the Liège Exhibition of that year. In common with all new standard types for heavy work, they have double chimneys. About the same time there appeared a very large 2-8-0 design for heavy goods traffic. As comparatively long runs have to be taken without replenishment of water and coal, the passenger engines have big eight-wheeled double-bogie tenders, but on the goods engines ordinary six-wheeled tenders afford ample provision. Track water-troughs, familiar to travellers on British railways, are unknown in Belgium and other Continental countries.

In 1935 a fine 4-6-2 appeared, together with fourteen sister locomotives. These are four-cylinder engines, and each weighs, with tender, in working order, approximately 200 tons. This is very heavy for a European “Pacific”. They are handsome engines, too, which is more than can be said for their five-years-old forerunners.

The boiler-sheathing is flush-topped, hiding the dome and top-feed arrangements, while the front-end screens and the smoke-box are arranged in exactly the same way as that invented and adopted by Mr. H. N. Gresley for his “Cock o’ the North” on the LNER. The coupled wheels have a diameter of 6 ft 5¼-in, which is greater than that found on most Continental locomotives.

Under the Belgian State Railways, after the war, locomotives were painted in a rather ugly shade of light reddish brown, which seemed speedily to deteriorate, first to a nondescript pink and then to no colour at all. When, however, the Belgian National Railways Company came into existence, the standard colour-scheme was changed to a deep bottle-green, with scarlet buffer-beams. As certain parts of many engines, including the chimney caps, are sheathed in polished brass, their appearance is very smart.

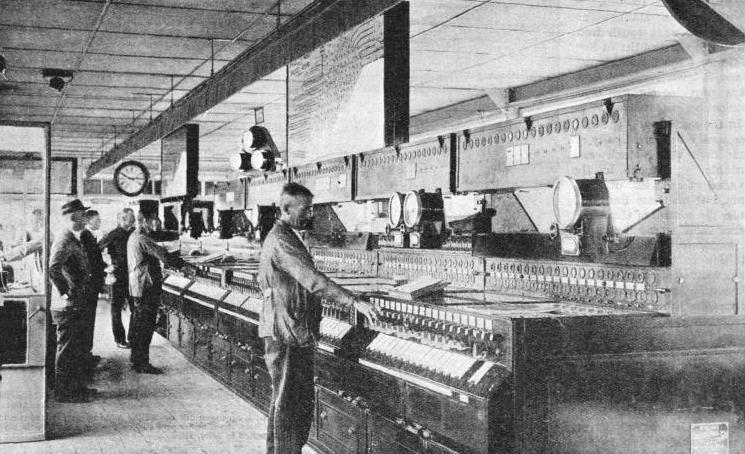

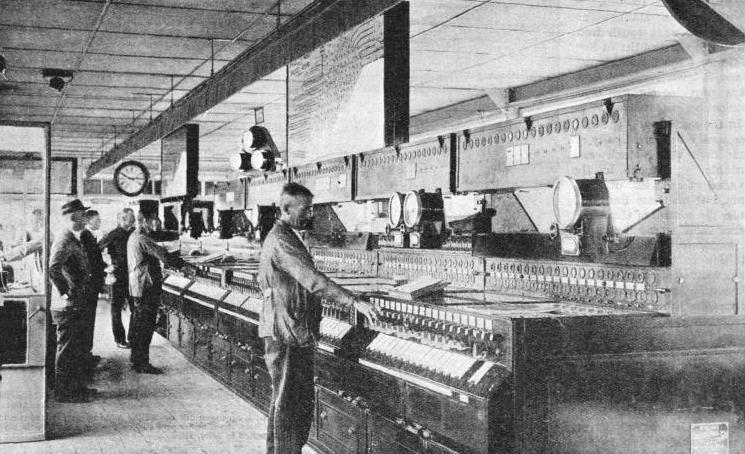

POWER OPERATED. The interior of a new electrically-worked signal-cabin at Brussels (Nord). The Belgian National Railways’ first track electrification was completed in April, 1935, when the twenty-seven and a half miles line between Brussels and Antwerp was electrified.

In the matter of passenger rolling-stock, until recently the Belgian standard was rather low, except for international trains. Even in these there were sometimes included Belgian coaches which compared unfavourably with the German and Polish carriages marshalled in the same train. On purely inland services there were hundreds of six-wheeled third-class carriages, with windows in the doors only. The ex-German “reparations” coaches were rather more up-to-date. A decisive step has now been taken, and fine all-steel corridor coaches are quickly replacing the old stock on both internal and international services. Before the war the only consistently good rolling-stock was represented by the Pullman-type carriages running in the special Brussels-Antwerp service. To-day it may be safely prophesied that, unless anything unforeseen occurs, the passenger rolling-stock of the Belgian National Railways Company will in a few years compare favourably with that of any other country on the European continent. In this connexion it should be remembered that Belgium was a pioneer in the use of the corridor coach. The first-class carriages of 1836, introduced for the extension of the Brussels-Malines line to Antwerp, had central gangways connecting the compartments, which held eight passengers each.

Until recently electric railway development in Belgium was more or less an unknown quantity. In 1929, however, the nine-miles-long suburban line from Brussels to Terveuren was selected for experiment, electric traction being inaugurated in 1931. This was a small independent railway. The Belgian National Railways’ first venture did not come to fruition until April, 1935, when the twenty-seven and a half miles line from Brussels to Antwerp was electrified. Direct current at a pressure of 3,000 volts is used, with overhead conductors, similar to those of the 1,500 volt electrification of the neighbouring Netherlands Railways between Dordrecht, Rotterdam, and Amsterdam. The Belgian National has also adopted the multiple unit system of working each train unit, consisting of two motor coaches, with pantograph current collectors mounted on the roofs, and two trailer coaches coupled between them. Central automatic couplers are used, as on the American railways, side buffers being dispensed with.

As in Germany, the railway stations of Belgium, where the bigger towns are concerned, attain a very high standard of architecture and arrangement generally. The Central Station at Antwerp is superb, and has one of the most striking exteriors of any station in the world. The architecture is of the elaborately ornamented Renaissance style; the roof has a lofty cupola containing four half-rose windows.

Gallant Speed Efforts

St. Pierre Station at Ghent is also a striking piece of architecture. An Arabesque style has crept in here; but views differ on the beauty, or otherwise, of the experiment. The battlemented walls add a medieval touch, which is enhanced by the conspicuous clock-tower.

The stations and bridges on the Belgian railways received their share of devastation during the war of 1914-18, for they were naturally made objectives for the shells and bombs of both sides. Altogether about 350 bridges of primary importance, together with an important railway tunnel, were completely destroyed, while a similar number of stations were rendered useless for some time. After the war temporary bridges were erected, and it was not until 1930 that these were replaced by modern structures of ferro-concrete. All-important sidings and marshalling yards had been blown up by the retreating Belgians, to hamper the advance of the enemy. At the present day the great marshalling yard at Antwerp is one of the most up-to-date in Europe, and loud-speakers are employed for the expedition of shunting operations. Belgium’s goods traffic, as may well be expected, is enormous.

Passenger train speeds in Belgium are generally lower than those in Great Britain, Germany, or France. The speed-limit has recently been raised to seventy-five miles an hour, but really fast long-distance running is hindered by the intricacy of the railway system, the nearness of important towns to one another, and the difficult curves and grading which occur, especially in the south-east and east. Nevertheless, some surprisingly fast running takes place where conditions permit.

The fastest purely Belgian trains run over the fairly level route between Brussels, Ghent, Bruges, and Ostend. During recent years a new direct line has been built between Brussels (South Station) and Ghent, and its length of 33·4 miles is covered by several trains in the remarkable time of 32 minutes, which works out at 62·6 miles an hour from start to stop. This applies in either direction; and various other expresses take 33 and 34 minutes. From Ghent to Bruges is 26·5 miles, and runs are made over this section in 26 and 27 minutes.

Between Bruges and Brussels. 59·9 miles, an express runs in 58 minutes, and the journey of 73·1 miles between Ostend Quay and Brussels is made in either direction in 74 minutes. These are gallant speed efforts indeed for so small a country. The longest non-stop run is over the difficult southward main line from Brussels to Luxemburg, and is made by the Edelweiss Pullman Express, over the 102½ miles between Namur and Luxemburg. The time of 126 minutes going south and 124 minutes coming north is extraordinarily good in view of the lengthy gradients - as steep as 1 in 60 - which have to be surmounted.

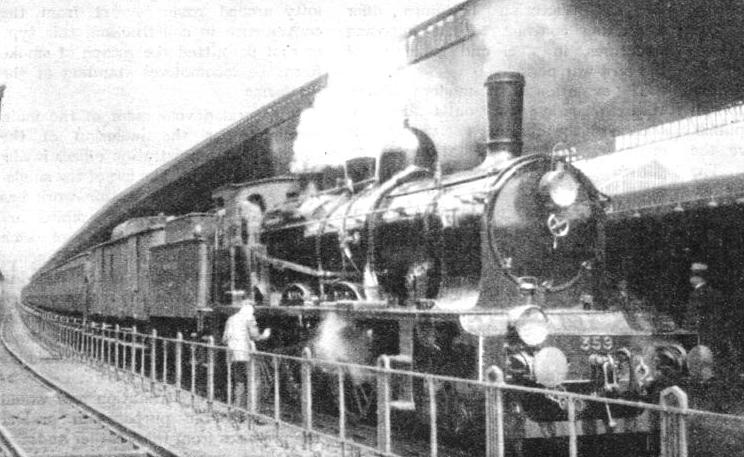

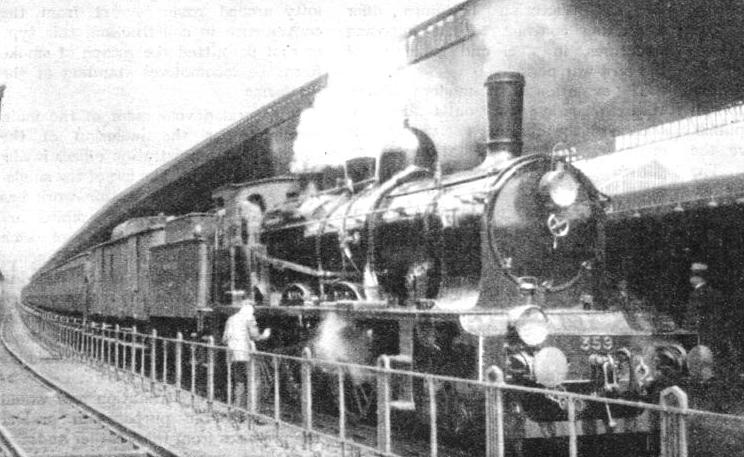

THE NORD-BELGE RAILWAY is a Belgian extension of the Northern Railway of France. The Northern Railway of France controls 105½ miles in Belgium which serve Liège, Namur, Dinant, and Charleroi. The photograph shows a local train about to leave Liège.

You can read more on “Germany and Holland” “The Northern Railway of France” and “Speed Trains of Europe” on this website.

AN EXPRESS PASSENGER LOCOMOTIVE, type “8”, with the 4-

AN EXPRESS PASSENGER LOCOMOTIVE, type “8”, with the 4-