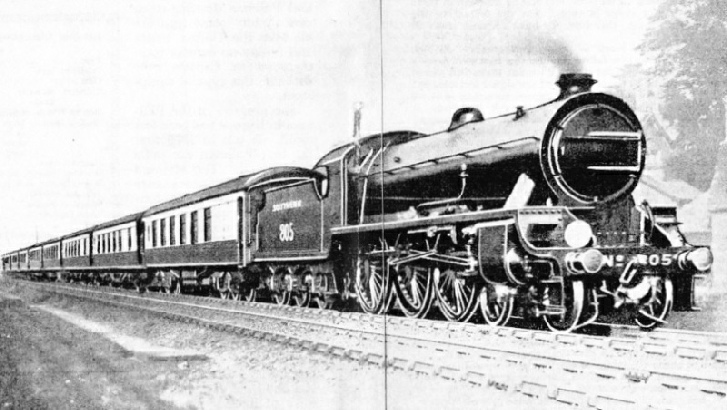

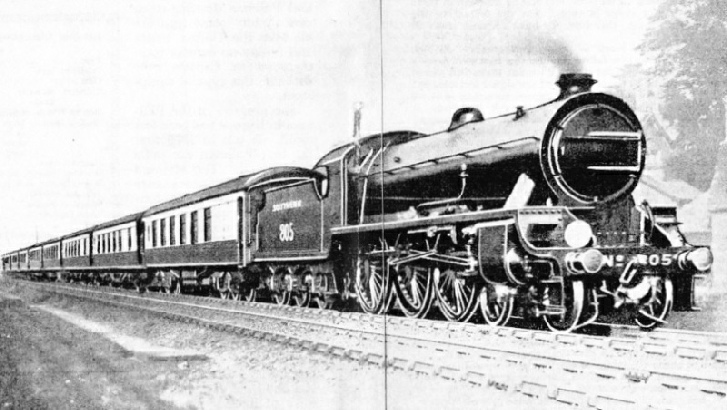

A Famous Train of the Southern Railway

FAMOUS TRAINS - 26

The “Southern Belle” passing Star Lane.

SIXTY years ago, a Chicago resident named George Pullman conceived the idea that travel in the United States of America might be made much more comfortable if some private individual with sufficient enterprise were to build a more luxurious type of car then ever previously employed, and then either lease the cars to the railways, or pay a rental to the railways for running them and recoup himself by the amounts paid by the passengers in supplementary fares. The idea caught on. Pullman sleeping cars and Pullman drawing-room cars rapidly came into use all over the United States and to-day no express train there or in Canada runs without this type of equipment.

The progress of the Pullman in Europe has been less rapid. It was in 1875 that the first Pullman car came to England. The Midland Railway, having seven years previously extended its tentacles southwards into its London terminus at St. Pancras, and being anxious to wrest passenger traffic from its old-established rivals on both sides, introduced Pullman sleeping cars as a special form of luxury equipment between London and Glasgow, and also Pullman drawing-room cars between St.

Pancras and Manchester. But on the Midland the Pullman idea did not find much favour, for some reason or other, and to-day – there is almost tragedy in the comparison – the bodies of the old cars may be discovered doing the duty of lineside shelters for shunters and others near the Central Station at Manchester, outside Nottingham, and elsewhere!

The next introduction of Pullman cars was in 1879 on the old London, Brighton and South Coast Railway, where, on the short journeys between London and the South Coast resorts, the open type of drawing-room car immediately found favour. All three sections of the present Southern Railway – the South Eastern and Chatham, the Brighton and the London and South Western, which worked them for some years between Waterloo and Bournmouth, abandoned them eventually in favour of restaurant cars, on the other two sections the Pullman business has gone up by leaps and bounds. Suffice to say that in the summer of 1927 no less than 114 trains were running daily on the Brighton and South Eastern sections of the Southern with Pullman cars attached – first class only in the latter case, but first and third-class on 44 of the Brighton trains and third-class only on six more.

It was in the year 1908 that the first daily all-Pullman express appeared in the British Isles, and to the London, Brighton and South Coast Company belongs the honour of its introduction. For ten years previously a first-class “Pullman Limited” express has been running from Victoria to Brighton and back on Sundays, covering the 51 miles in the even hour, but there had been no such time operating on week-days. The new train was therefore arranged to leave Victoria at 11 a.m. daily and to reach Brighton at 12 noon. To mark the occasion suitably, a distinctive name was chosen – that of “Southern Belle” for the new service, and in view of the adoption 15 years later, of the title “Southern Railway” by this group of lines, the name could scarcely have been improved upon.

An entirely new set of twelve-wheeled Pullman cars, seven in number, was built to make up the “Southern Belle,” and the boast on their introduction that this was the most luxurious train in the world was at that time very likely not without foundation. The whole set of seven cars was required for Sunday use, but on weekdays this formation was generally cut down to four, as for some years first-class passengers only were carried and four coaches provided sufficient accommodation. It was next thought that this significant coaching stock was not being put to sufficient use, and it was

therefore decided that the “Southern Belle” should make a couple of additional journeys between her arrival at Brighton at 12 noon and her departure for Victoria at 5.45 p.m. A very quick “turn-round” was therefore arranged, the “Belle” leaving Brighton for a 60-minute run to London at 12.20 p.m, and coming down again from Victoria to Brighton at 3.10 p.m. This increased the mileage of the stock from 102 to 204 miles daily.

It was therefore realised that four-coach trains, even if the cars are all Pullmans, are a wasteful proposition in these days of powerful modern locomotives, and a concession to democracy was decided upon in the form of an addition on weekdays of ordinary third-class coaches to the train formation. This proved so immensely popular that, after the Brighton Company had set up an entirely new standard in third-class travel by providing Pullman cars for third-class passengers, in 1915, it was finally decided to substitute third-class Pullman cars for the ordinary third-class coaches. This last substitution has taken place since the war, and once again, therefore, the “Southern Belle” is an all-Pullman express. Only in the summer is an additional brake-van attached for the conveyance of luggage; at other times Pullman cars alone are included in the formation.

During the height of the summer the “Southern Belle” shares with the 10.45 a.m. Pullman boat express to Dover the distinction of being the heaviest Pullman train in the country, and the task before the locomotives of completing the 51 miles between Victoria and Brighton in the hour is by no means an easy one.

In the earlier days of the “Belle” a variety of locomotives undertook its working. Often the four coach train, and at times the seven-coach Sunday express, was entrusted to one of the fine Earle Marsh superheated 4-4-2 tanks of Class “I.3”, which kept time without difficulty. On other occasions these would be supplanted by the large “Atlantics” – either the non-superheated engines of the 37–41 series, or the later superheated developments, Nos. 421–426. Then came the turn of the 4-6-2 tanks “Abergavenny” and “Bessborough”, and, later still, of the magnificent Billinton 4-6-4 express tanks of the “Charles C. Macrae” series, the last-named being powerful express engines in every respect other than that of carrying a separate tender for fuel and water supply. They were provided, indeed, with the largest cylinders ever fitted to a British two-cylinder single locomotive (other than the similarly-dimensioned Urie 4-6-0 engines of the London and South Western), 22-in in diameter by 28-in stroke, with the result that their tractive effort reached the high figure on 24,175 lb.

Now, however, in the march of progress, the ubiquitous 4-6-0 “King Arthur” tender engines are chiefly concerned in the working of the “Southern Belle” and the other Brighton 60-minute expresses. A special series of these engines has been built, provided with six-wheeled tenders instead of the eight-wheeled tenders in use on other sections of the Southern line, as being more suited in coal and water capacity to the short runs of the Brighton section. The 4-6-4 tanks still take a

hand in running the “Belle” at times, and sometimes also the 2-6-4 Maunsell tanks of the “River” class; but in general it is a “King Arthur” that will be found at the head of the train. The times of the service have been altered, by the way, since “systematic” departure times were adopted on the Central Division, in common with the other divisions of the Southern Railway. So the down “Southern Belle” leaves Victoria at 11.5 a.m. and 3.5 p.m., and the return times are 1.35 p.m. and

5.35 p.m. from Brighton to Victoria.

We shall find the train probably, in the last platform but one at the extreme right-hand side of Victoria station, with the third-class Pullmans in front and the first-class behind, to a total on weekdays, of eight or nine cars in the winter and probably ten in the summer. The hardest effort required of the engine, going south, is the rise out of Victoria to the Grosvenor Bridge over the Thames. This is slightly easier in grading than from the South Eastern side of the terminus, being 1 in 64 as against 1 in 61; but even so the half-mile of climbing, starting right off the platform end, is a tough proposition, more especially as rear-end assistance is seldom employed.

Once across the river we accelerate rapidly, swinging over the South Western main line to run parallel with it as far as Clapham Junction which we pass at about 45 miles an hour, some six minutes after starting. Between here and Brighton the main line has three well-defined summits, each crowned with a tunnel; these are near Merstham, some 18 miles after starting, Balcombe, 32½ miles, and Clayton, 46¼ miles, the line dropping between each two summits to its lowest points at Horley, 26 miles out, and Wivelsfield, just beyond Haywards Heath and 40½ miles from the start. Between Croydon and Brighton the gradients are mostly in long even stretches at 1 in 264, up to the tunnels and down to the hollows, the only steeper lengths being 2¾ miles at 1 in 165 from Coulsdon up to Quarry Tunnel, and four miles mostly at 1 in 200 through the tunnel and down to Earlswood.

On the rising gradients from Clapham to Balham at 1 in 166 and 94, we fall to about 40 m.p.h. or a shade under, but then probably work up to 55 m.p.h. or thereabouts through Streatham Common. On the farther rise, to Selhurst, speed falls again somewhat and is then moderated through the maze of junctions that brings us on to the original London and Brighton main line at Windmill Bridge, just south of Croydon. East Croydon, 10½ miles from the start, is passed in about 16 min, leaving 44 min. only for the remaining 40½ miles to Brighton.

It is a long stretch “against the collar” from Croydon up past Purley and Coulsdon to “Quarry” summit. At Coulsdon we leave behind us the electrified lines and cross over the old joint Brighton and South Eastern tracks to the right of them, on to the avoiding line that the Brighton Company opened in 1900 to give them an independent route from here to Earlswood, on the other side of Redhill, where the original main line is rejoined. Up the 1 in 264 to Coulsdon we maintain 50 an hour, or slightly under, falling to 45 or less on the 1 in 165 ere we enter Quarry Tunnel, which is just over a mile in length.

Then follows a swift dash down past Earlswood to Horley, where we may touch anything from 65 up to 75 m.p.h., according to driver and engine. The impetus of this probably will carry us up the 1 in 264 past Three Bridges to Balcombe Summit, which is just before the entry to Balcombe Tunnel, at between 50 and 55 m.p.h. Then another downward dash past Haywards Heath and Wivelsfield to Keymer Junction, where the Eastbourne line diverges on the left, will produce a second maximum probably over 70 m.p.h. Rising to and through Clayton Tunnel, which also exceeds a mile in length, we probably drop slightly below 50 m.p.h. and then, with very gentle running down the final incline to Preston Park, we draw slowly round the sharp curves and up the long platform at Brighton Central, to a dead stand probably just on the stroke of 12.5 noon. Timekeeping is none too easy with all the congestion of this busy route, but it is seldom that the “Belle” is more than a minute or two out at either end of her journey.

It is of interest to note, by the way, that the fastest time ever achieved between London and Brighton was made by the

4-4-0 engine “Holyrood,” with the down Sunday “Pullman Limited” on 26th July, 1903, when the journey of 50.9 miles was completed in the remarkable time of 48 minutes, 41 seconds. It is claimed that on that occasion a maximum speed of 90 miles an hour was attained at Haywards Heath.

The “Southern Belle” in London Brighton & South Coast Railway days. This luxurious train runs daily in each direction between Victoria and Brighton (51 miles) in 60 minutes. On Sundays it consists entirely of 1st class Pullman cars, but on weekdays it has two or three ordinary 3rd class coaches added. It is shown hauled by a 4-4-2 tank engine.

You can read more about “The Atlantic Coast Express” , “The Dover Pullman Boat Express” and “The Folkestone Flyer” on this website.