© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The Dover Pullman Boat Express

Riding on the “Golden Arrow” before it was so named

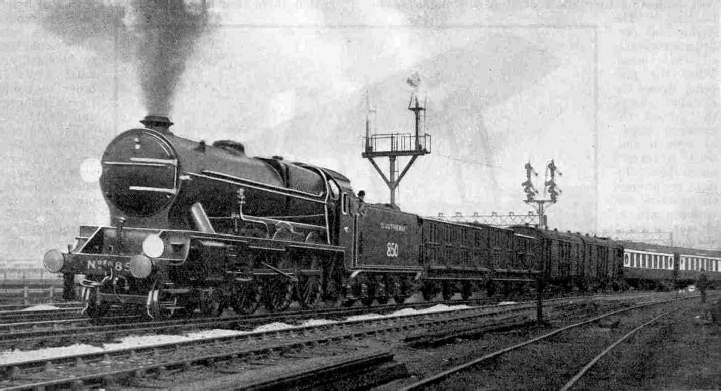

Dover Pullman Express leaving Victoria. Engine No. 850 “Lord Nelson”.

WHAT the real name of this train is I could not say. For many years past the “Eleven o’clock” service from Victoria has been familiar to travellers all over the Continent but our train cannot rightly be called the “Eleven o’clock”, because it starts at 10.45! It is, in fact, a first portion of the 11 a.m. train, designed to give its fortunate passengers the choice of places on the boat at Dover. Sometimes it is called the “Golden Arrow”, but that name belongs to the French express that runs in connection on the other side of the Channel, and which has been previously described on this website.

The rudest name that I have heard bestowed upon the 10.45 down is that of the enginemen who, in joint recognition of the beautiful cream and umber livery of the Pullmans arid the enormous weight of the train, have nicknamed it the “White Elephant”. It will be agreed that so famous a train as this needs a name of its own, and one day perhaps the Southern Railway authorities will think out some telling designation, to rank with the “Southern Belle” and the “Atlantic Coast Express”. Meanwhile it is difficult to write an article of this character in description of a train without a name!

So far from being a “White Elephant” in reality, the 10.45 a.m. from Victoria is one of the best-

Actually you can reach Paris in the best time of the day by catching the second part of the train, which leaves Victoria at 11 a.m. On this, too, you can make a Pullman journey through to Paris, as at least four Pullmans are usually included in the formation. By catching the “Golden Arrow” at Calais you may reduce your journey time between London and Paris to 6 hours, 40 minutes.

The 11 o’clock train also carries ordinary first and third class passengers, in corridor coaches that are vestibuled to the Pullman cars, so that meals and light refreshments can be served in any part of the train. At slack times, between the Continental “seasons”, a full train of Pullmans is not always required on the 10.45, and at such times some of the cars are replaced by three or four corridor coaches. But you will customarily find nine of the latest and most luxurious 8-

Behind that comes the accommodation for registered luggage. This is no inconsiderable item; it requires two 4-

The two luggage vans weigh 13 tons each, the two trucks 10 tons each, and the eight boxes about eight tons in all, making together an addition of 54 tons to the empty train weight. On the occasion of the photograph at the head of this article, by the way, owing to the departure of the French President after his State visit to London, the usual No. 2 platform was not available, so that “Lord Nelson” had to drive into No. 2 for the luggage, and then work the extra vehicles across to No. 6, where they were attached in front of the 10.45 train instead of in rear. We have now a total of 446 tons, and with passengers and their luggage we may expect the total weight of the train, behind the engine tender, to be in the neighbourhood of 470 tons.

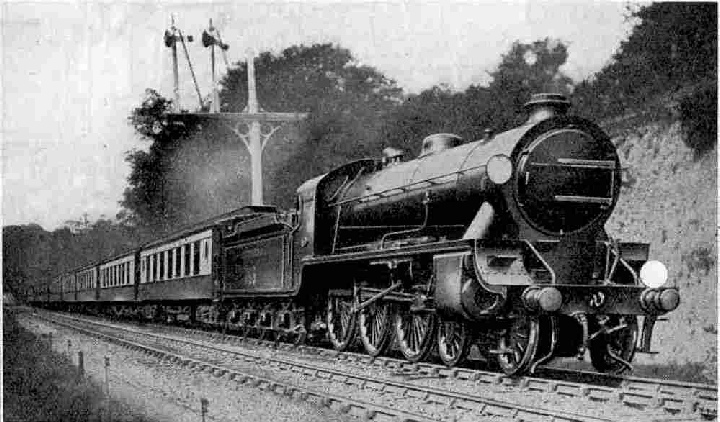

What the introduction of the “King Arthur” 4-

It must not be thought that the introduction of heavy six-

Dover Pullman Express passing Sandling Junction. “King Arthur” 4-

Next the route between Swanley Junction and Ashford, via Maidstone East, was tackled, and the work on this section is now complete, so that boat expresses may be worked via Maidstone East, if so required. None of the regular down trains is booked to go by this dreadfully hilly and slack-

There is still another route to Dover, and that is the old Chatham and Dover main line, which goes by way of Chatham, Faversham and Canterbury. Weak bridges on this route are also in course of being dealt with, so that ultimately the Southern Railway will have the choice of three routes for working their increasingly important Continental services between London and Dover. Whenever possible, however, the Tonbridge route is used, as it is both the shortest and the least heavily graded, which are considerations of no small moment in the working of heavy trains like these.

But I am wandering from my real subject, and it is now high time that we should repair to Victoria and find the train that we are about to accompany. We are in luck on this particular day, for we find at the head of the string of beautifully-

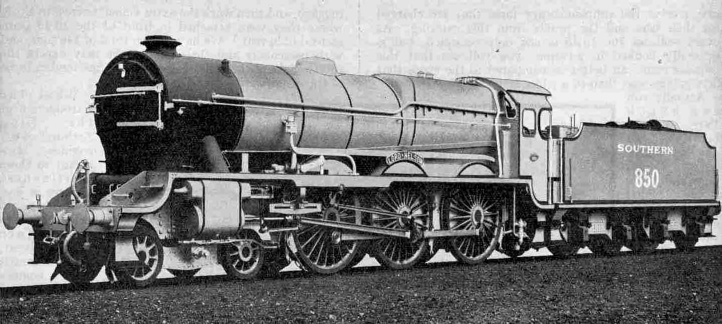

4-

We shall find, on our journey, that the boiler and firebox are of more than ample size to furnish all the steam required to make that tractive force effective, and that the exceptional adhesion weight of 62 tons, on the three coupled axles, will enable the maximum power developed by the engine to be transmitted to the rail without slipping. This wonderful locomotive was described at length in the article “Britain’s Most Powerful Loco”, and I shall not stay further to go over the details of his construction. But as I have had quite recently the privilege of riding to Dover on “Lord Nelson’s” footplate, on this very express, I want you to imagine that we are occupying that jealously-

Just a word or two about Victoria Station while we are waiting for the “right-

Now that the Southern Railway has taken control, part of the separating wall has been knocked down, and the two stations have been thrown into one, the platforms now being all numbered consecutively from the South Eastern across to the Brighton side. We are standing at the longest South Eastern platform -

Southern Railway 4-

Out of Victoria the rise to the Grosvenor Bridge over the Thames is extremely steep. Brighton trains have to mount an incline of 1 in 64, but we, taking the inside of the curve, have in front of us the even more formidable ascent of 1 in 61. Worse still, it begins right off the end of the platform, so that there is no chance of “taking a run” at it. As I have mentioned previously, it is customary for the engine that brought in the empty coaches to help at the start by giving a friendly push in rear to the top of the bank, but our train is so long as to occupy the full extent of the platform, so that it has been pushed instead of pulled in, and there is therefore no engine at the far end. Realising this, our crew have had the foresight to drop some sand on the rails from the trailing sandboxes of “Lord Nelson” as he was backing down on to the train, to prevent slipping as we get away.

At last comes the “Right away!” Looking at the indicator of the valve motion we see that “cut-

But it will be many miles before we may expect to see anything of the speed capacity of our mount. Almost uninterruptedly for 18 miles we shall climb, and even where there are “breathers” in the ascent, we dare not take advantage of them, as we are sandwiched in between frequent electric trains, using the very metals that we are running over. So we notice that the driver now brings the cut-

We were reminded by the rapid puffing of “Lord Nelson” at the start that the unusual disposition of the cranks of the four cylinders results in eight “beats” to each revolution of the driving wheels, instead of the usual four. The exhaust has now quietened until it is practically inaudible, but we notice the effect of this crank arrangement on the fire, in the beautiful evenness of the blast. The fire-

Through Brixton and Herne Hill we are doing about 40 miles an hour. Immediately after this comes the stiff rise to Sydenham Hill, which demands a little more regulator opening. But with barely half regulator, and still at 30 per cent cut-

Only those who have travelled on the footplate can realise the extraordinary sensations of passing through a tunnel on the engine. The roar and rattle of the engine itself in the confined space of the tunnel walls; the steam and smoke sweeping past and sucking back into the cab; the glow of the fire lighting up the cab and its occupants, amid the Stygian blackness of the bore; all combine to leave an unforgettable impression on the mind. But we shall probably be glad when we are out once again into the fresh air.

This is, by the way, an exceptional route for its tunnels; Penge is 1¼ miles in length; then come Chelsfield and Polhill, before and after passing Knockholt, the latter 1½ miles in length; Sevenoaks Tunnel is all but two miles in length and last of all there are three tunnels between Folkestone and Dover, of which Abbott’s Cliff is 1⅛ miles in length. The tunnels do not fail to leave their “trade marks” on the faces of the travellers in the cab, because tunnels are invariably the dirtiest parts of a footplate journey.

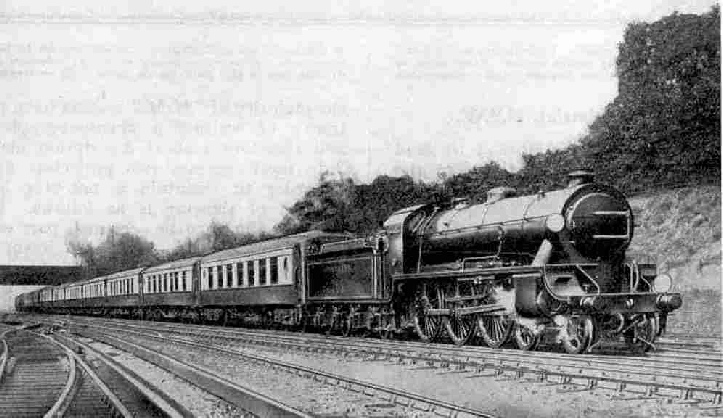

Dover Pullman Express passing Bickley. “King Arthur” 4-

The regulator is nearly closed for the down-

Swiftly gathering speed down through Polhill Tunnel, we dash through Dunton Green at just over 60 an hour and take the sharp rise from there to the mouth of Sevenoaks Tunnel “at the double”, so to speak. The two miles through the tunnel fall at 1 in 144, and the five miles on to Tonbridge Junction at 1 in 122, and the good alignment of the track here permits of speeds -

the green warning board indicating engineering works in progress, and the “C” sign, showing where they commence, brings us down to 15 miles an hour at Hildenborough. Shortly after regaining speed we have to slow yet again for the curve through the junction at Tonbridge. Over the first 30½ miles of our journey we have taken 47½ minutes.

We have now before us one of the straightest lengths of line in the British Isles, with only the gentlest of undulations, and of this “Lord Nelson” will take the fullest advantage. The driver opens the regulator to one-

Another permanent way warning board ahead! It is renewal of track this time, near Smeeth, and once again our proud progress must be stayed until the welcome “T” sign indicates that normal speed maybe resumed. So on past Westen-

On through Folkestone Junction and the tunnel we speed; then through the Warren, with its marked evidences of constant falls of the cliff face, and the trouble and expense that they have given to the railway company. Abbott’s Cliff Tunnel is threaded, and we espy on our right all that remains of the beginning that was once made to bore under the English Channel. At last the peculiar tunnels under Shakespeare’s Cliff are in view, and we take the “left-

A shunting engine comes and hitches the vans and the two trucks off the rear, carrying them round on to the Quay and we regretfully say goodbye to driver and fireman, who run back to the locomotive depot to get ready for working the 3.30 p.m. boat express back to Victoria. Such is a day in the life of the “Lord Nelson”.

You can read more on “The Golden Arrow”, “The Fleche d’Or” and “The Newhaven Boat Express” on this website.