© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

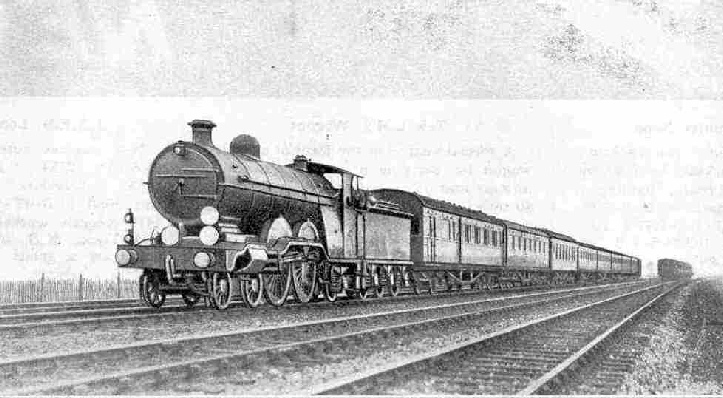

The “Newhaven Boat Express”

Southern Railway

The “Newhaven Boat Express” at speed near Earlswood. The engine is an “Atlantic” (no. 41) of the original series, which have now been rebuilt and superheated.

THERE is a tremendous attraction about Continental travel. There is the experience of a real thrill brought about by the first landing on a foreign shore, by hearing another language, by eating different food, by seeing strange sights, and by thus beginning a holiday that is, in every sense of the word, a “change”.

The Southern Railway is the principal gateway for us to these lands of enchantment. Amalgamation of the three railways serving the South Coast of England -

Malo and Caen in France; Dover to Ostend in Belgium and Gravesend to Rotterdam in Holland. Most of the passenger traffic to France and Central and Southern Europe generally goes by the Dover-

Newhaven, the nearest of all cross-

One reason for this weight is that, as with all the Continental trains now, the Southern authorities use on this service their latest and most comfortable type corridor coaches, each weighing 32 or 33 tons, in conjunction with a 12-

The working of the “Newhaven Boat Express” whether by day or night, is generally entrusted to the fine “Atlantic” engines of the late Brighton Company. There are two distinct series of these locomotives; the first, turned out in 1906, consisting of five engines -

In the second series the cylinders were further enlarged, to the big figure, at that time, of 21-

Work over the Brighton main line of the Southern is hard work! Out of the terminus at Victoria the line rises straightaway on a gradient which, though short, is as steep as 1 in 64, until the Thames has been crossed by the Grosvenor Bridge. From the South-

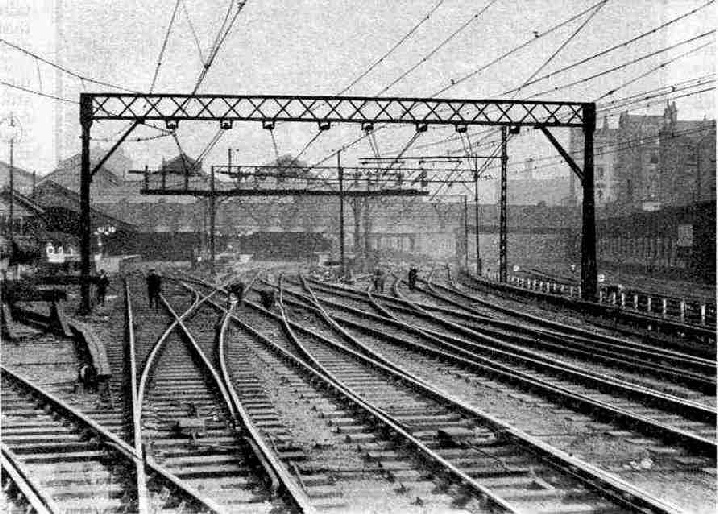

The maze of electrified track at Victoria Station. This station is one of the largest in London, with a total of 17 platforms and an area of 23 acres. It combines the old South Eastern and Chatham terminus on the right-

When the train is getting well away towards Clapham Junction, there comes a slack over Pouparts junction, more pronounced in the up direction than the down; and after that, before the engine has had time to recover, a sharp rise to Balham Junction. From there onward, although there are one or two level strips, the grades are almost entirely against the engine until we have entered Quarry Tunnel, by which the North Downs are pierced north of Merstham. From there we sweep downward to Earlswood and Horley; up through Three Bridges to Balcombe Tunnel; and down through Haywards Heath to Wivelsfield where, at Keymer Junction, we have to slacken severely in order to diverge to the left for the Lewes line. Through Lewes itself -

Punctually at 10 a.m. we leave Victoria. If we have not been banked in rear, we shall probably breast the rise on to Grosvenor Bridge at little over 20 miles an hour. Presently, just after the Eastern Division main line has left us for Ramsgate and Dover, we cross the Western Division main line and bear round to the right to come down and join ourselves to the immense width of trackage that heralds the approach to Clapham Junction. This well deserves its reputation as one of the busiest stations in the world; it claims to handle no less than 1,730 trains every day. Immediately after passing through, in about six minutes from the start, we tear left and part company from the Western Division lines again. On the more level stretch through Streatham and Norbury we may attain well over 50 miles an hour, later slowing through the maze of junctions that bring us on to the London Bridge main line at Windmill Bridge Junction, prior to stopping at East Croydon. I use the word “maze” advisedly, as this certainly must be one of the most exceedingly complex railway layouts that exist on the surface in any part of Great Britain.

I well remember once coming up in the opposite direction, when my train, with portions from Brighton and Worthing, had been divided from Haywards Heath. We were delayed by signals somewhere about Purley, with the result that the second part, which had been turned on to the “Local” line at Coulsdon, caught us up. Then there ensued a most exciting “neck-

The Croydon stop of the "Newhaven Boat Express" is a relic of the times when there were two parts of the train, one from Victoria and the other from London Bridge, which were joined together here, Even now that all the Continental traffic of the Southern has been concentrated at Victoria the Croydon stop is still maintained, because of the importance of the local connections. We are due to leave there at 10.19 a.m, and for the 46 miles from East Croydon to Newhaven Harbour we are allowed the ample time of 67 minutes. The line rises at 1 in 264 through Purley to Coulsdon, where we bear rightward across the original Redhill main line to get on to the “New” line, opened by the late Brighton Company in 1900 to give relief to their fast traffic to Brighton, Eastbourne, Newhaven and Worthing.

This avoiding line begins with a peculiar “covered way” under some private grounds, which the railway company was compelled by their owners to make; here for a short space the gradient is 1 in 100 up. Then, as we mount through a deep chalk cutting -

How comes another swift descent, past Balcombe, over the fine Ouse Viaduct, through Haywards Heath at anything up to 70 miles an hour or so, and then down to 30 at Keymer for the junction. After once again regaining speed, we may reach the “sixty” line as we descend across open country towards Lewes. The approach to the county town is heralded by a tunnel, in which we reduce speed to a snail’s pace, as the station is on an extremely sharp curve. If we are through Lewes in 55 minutes from East Croydon time-

On leaving Lewes we appear to be making straight for the great rampart of the South Downs, but almost immediately we bear right again, and presently, at Southerndown Junction, diverge to the right again from the Eastbourne line. A level run alongside the tidal River Ouse, and ere long masts and funnels and other evidences of maritime activity bear into view. We run slowly through Newhaven Town Station, past the “through” annexe of Newhaven Harbour Station, to Marine Station, with the Dieppe steamer at the quay alongside, at 11.26 a.m.

Newhaven is the nearest but one to London of all cross-

You can read more about “The Dover Pullman Boat Express”, “The Golden Arrow” and “The North Country Continental” on this website.