© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The “Aberdonian”

A Famous Train of the LNER

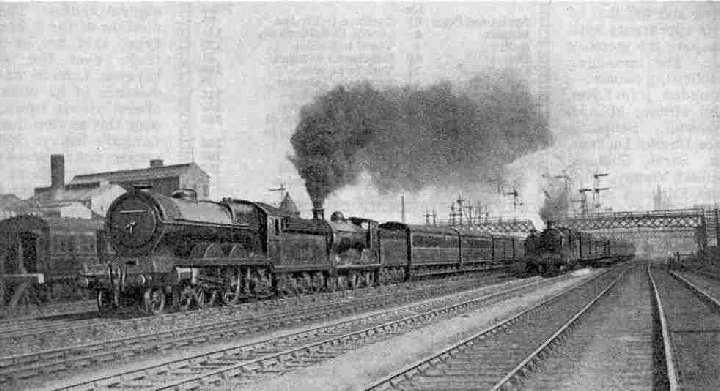

The “Aberdonian” leaving Aberdeen, hauled by 4-

IN describing the runs of the express trains already dealt with in this series of articles we have in every case started our journey at the London end, with the solitary exception of the “Folkestone Flyer”. We have thus worked from London northwards, southwards, eastwards or westwards as the case might be and the result has been, that by the time we have reached the final and furthest most limits of each trip the precious space available has been exhausted. The last stages of the run, therefore have been passed over very hurriedly and I have had to excuse this, as the lynx-

But I know my friends in Aberdeen too well to attempt any such excuse in the case of a train that bears the name of their illustrious city. I should not like to think of my good friend the Editor being deluged with complaints from indignant Aber-

The “Aberdonian” is an historic train. It was away back in 1895 that the down “Aberdonian” was concerned in one of the most sensational happenings in British railway history. Seven years earlier, the companies comprising the East and West Coast routes had reached so great a pitch of excitement owing to the fact that the East Coast people had seen fit to admit third-

This contest, however, was mild indeed in character as compared with that which in 1895, followed the completion of the East Coast Route in the opening of the great bridges across the Firth of Forth and Firth of Tay. The “Race to Aberdeen” began modestly enough; the first step was merely that the West Coast companies announced acceleration by 10 minutes of the time of their down “Aberdonian”, thereby coming within 5 minutes of the time of their rivals. Promptly the East Coast

companies indicated a corresponding acceleration. From that time forward, in July and August, 1895, acceleration succeeded acceleration in bewildering sequence, until hours had been cut from the schedules of but a few weeks before. Finally the timetable was scrapped altogether, relieving trains being run behind the racing “flyers” to pick up passengers who might be stranded by the early running of the expresses.

So far as the East Coast was concerned the culmination came on the night of 21st August, when the 523½ miles from King’s Cross to Aberdeen, inclusive of stops at Grantham, York, Newcastle, Edinburgh and Dundee, as well as the terribly difficult gradients and sharp curves north of Edinburgh – whose acquaintance we shall make in a moment – not to mention a stretch of single track between Arbroath and Kinnaber Junction, north of Montrose, were covered at an average rate of over 60 m.p.h. throughout, in 8 hrs. 40 min. Not to be outdone, the West Coast, with their 915-

So far as the East Coast was concerned the culmination came on the night of 21st August, when the 523½ miles from King’s Cross to Aberdeen, inclusive of stops at Grantham, York, Newcastle, Edinburgh and Dundee, as well as the terribly difficult gradients and sharp curves north of Edinburgh – whose acquaintance we shall make in a moment – not to mention a stretch of single track between Arbroath and Kinnaber Junction, north of Montrose, were covered at an average rate of over 60 m.p.h. throughout, in 8 hrs. 40 min. Not to be outdone, the West Coast, with their 915-

There are, however, a good many reasons why the tremendous speeds of the “Race to Aberdeen” could never be made permanent. In the first place, the average passenger, entraining at either end of the journey at the comfortable hour of half-

When we join the up “Aberdonian” at Aberdeen, we shall probably find the weight of the train to be but little less than 400 tons all found. The composition of the express varies considerably, as between the winter and the summer service, but we may be certain of finding, next the engine, a restaurant portion for Edinburgh, consisting of a 12-

London portion – the “Aberdonian” proper – which is generally one of the magnificent articulated “twin” sleepers, weighing 62 tons, a composite corridor coach, one or two third-

North British “Atlantics”, or, if heavier still, to a double-

Almost certainly we shall find one of the “Atlantics” at the head of the train. Disappointing in their early performance, the Reid “Atlantics” of the late North British Railway may be numbered among the numerous classes of express locomotive in this country whose work has been transformed by the addition of superheating equipment. It may be a matter of surprise, in view of the exceptional difficulty of the grading of all the chief routes over which they work, that their designer did not choose the 4-

We must spare a glance, first of all, for the fine Joint Station at Aberdeen, before we start our journey. It was at one time the headquarters of the Great North of Scotland Railway which, in the grouping, becomes the Great North Scottish Area of the LNER. It is interesting to note that, in relation to the parent system, this area is “marooned”, being cut off physically from the nearest point on the main LNER system, just north of Montrose by 38 miles of “foreign” line, once Caledonian, and now of course, LMS territory. Once we are past Ferryhill junction, on the south side of Aberdeen, therefore, the “Aberdonian” has to exercise what are known as “running powers” over LMS metals, before it passes again on to those of the LNER. Aberdeen Joint Station is partly terminal, with four terminal platforms at the north end and five at the south end, as well as four long through platforms, 1,596 ft in length, giving through communication from north to south. It is from one of the south platforms that we start away, at 7.35 p.m.

The famous Tay Bridge.

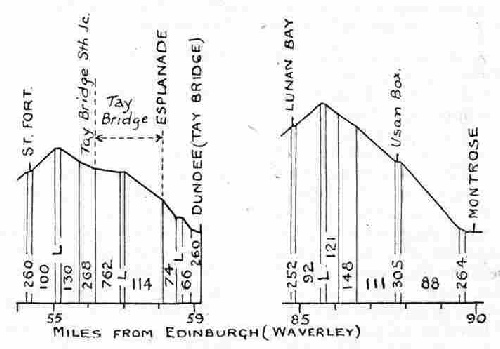

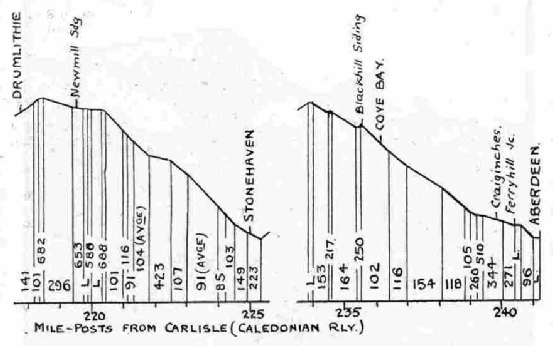

The timetable of the “Aberdonian” reveals no startling feats of speed, but the gradient diagrams reproduced will show something of what is before the engine in the four successive starts from Aberdeen, Stonehaven, Montrose and Dundee. From Aberdeen we must toil for six miles without a break, in the first ½-

the climb.

Then follows a descent to Stonehaven, where the sight of the distant signal “on” prepares the driver to stop, as this is a “conditional” halt, made only when passengers require to be picked up. I once remember a driver being thus compelled to stop at Stonehaven to pick up one solitary lady, and I was ungallant enough to think that it would have been cheaper to have compensated her suitably, if need be, and sent her on by the train in front! For at Stonehaven, at the bottom of steep gradients in both directions, we need all the momentum we can muster to help us up the formidable ascent to Drumlithie, and a stop destroys it completely, compelling a restart on an incline of 1 in 149.

Once more, however, we get away well, and with the fillip to the speed given by the short 1 in 423 “breather” in the middle of the climb, which again brings us up to 35 or even 40 m.p.h., We pass Drumlithie, seven miles from Stonehaven, in between 13 and 14 minutes. If we have taken 25 min. to run the 16¼ miles from Aberdeen to Stonehaven, and have stopped there a minute, we have now 18 min, or a little over, in which to complete the 17 downhill miles to Montrose. This is a matter of no difficulty. We may and probably shall exceed 70 m.p.h. at Fordoun, and again below Marykirk – exchanging our East Coast views temporarily for a magnificent prospect of the Grampian Hills far on the west of us – until a drastic slowing indicates the approach of the Kinnabar Juction.

Kinnabar is a name of historic memory. Here it was that the down racing trains of 1895 converged on to the one track for the final 38 miles of their run, and to the lasting credit of the signalman there be it said that on one night, when the “is the line clear” bells for both the racers sounded simultaneously in his cabin, he chivalrously gave the “foreigner” the preference –Kinnabar is, of course, a Caledonian cabin – so that on that night the East Coast train arrived in Aberdeen first. Our severe slowing is not alone in order to take the converging junction, but the “tablet” for the single-

From Montrose there is another bad start, steeper, even if shorter, than those from Aberdeen and Stonehaven. The single line continues from here over the summit, 4½ miles distant, to Lunan Bay, where double line running commences, and downhill we run swiftly to Arbroath, the next stop. For the 13¾ miles from Montrose to Arbroath the time allowance is 21 min, and in view of the severity of the immediate rise, this proves none too much. Strikingly in contrast, the next 17 miles to Dundee, right along the sea coast past the well-

From Montrose there is another bad start, steeper, even if shorter, than those from Aberdeen and Stonehaven. The single line continues from here over the summit, 4½ miles distant, to Lunan Bay, where double line running commences, and downhill we run swiftly to Arbroath, the next stop. For the 13¾ miles from Montrose to Arbroath the time allowance is 21 min, and in view of the severity of the immediate rise, this proves none too much. Strikingly in contrast, the next 17 miles to Dundee, right along the sea coast past the well-

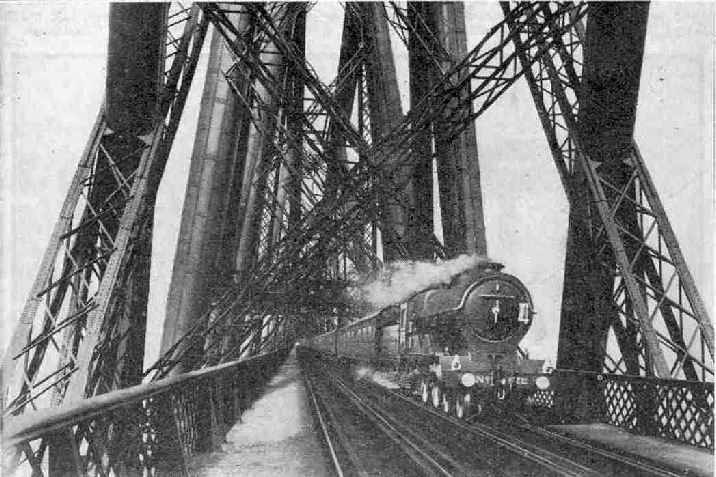

It is, of course only in the height of summer that the engineering wonders of the next section of the journey are clearly visible. From Dundee, where quite possibly we may change engines – substituting for our “Atlantic” another, or a “Director” 4-

The Tay and the Forth Bridge between them have been the making of the East Coast Route, so far as concerns the portion north of Edinburgh. The Tay bridge, which owing to the comparative shallowness of the Tay estuary, was considerably the easier engineering proposition of the two, was the first to be completed. In the earlier design, however, insufficient allow-

At a later date the Tay Bridge was re-

Past Leuchars Junction and Cupar to Ladybank Junction the gradients consist of moderate undulations only, save for a short rise at 1 in 107 to Springfield, and we may expect an average speed of round about a mile-

Then follows another sharp rise for two miles to the 29th mile-

The “Aberdonian” on the Forth Bridge.

Once again we have lost momentum where we most need it, and we are to do so yet again by the equally bad slowing through Inverkeithing, as between these places we have to rise for three miles at 1 in 100 from Arberdour up to Dalgetty cabin, and then, having recovered speed on the ensuing down-

In such circumstances the schedule of 84 min. for the 59¼ miles from Dundee to Edinburgh is far from excessive; with such a load as this, indeed, it is distinctly “tight”. To Tay Bridge South Box, 3½ miles from the start, the time allowed is 8 min, and the next 16½ miles to Ladybank consume about 20 min. 11 minutes for the 8¼ miles over Lochmuir to Thornton, and 13 min. for the 10½ miles to Burntisland leave no margin. Then comes 10 min. for the seven miles to Inverkeithing, 8

min. up and over the Forth Bridge, to Dalmeny, and 14 min. – the only part of the schedule which, given a perfectly clear road to Waverley, allows a small recovery margin – over the final 9½ miles from Dalmeny into Edinburgh, where we are due at 10.50 p.m.

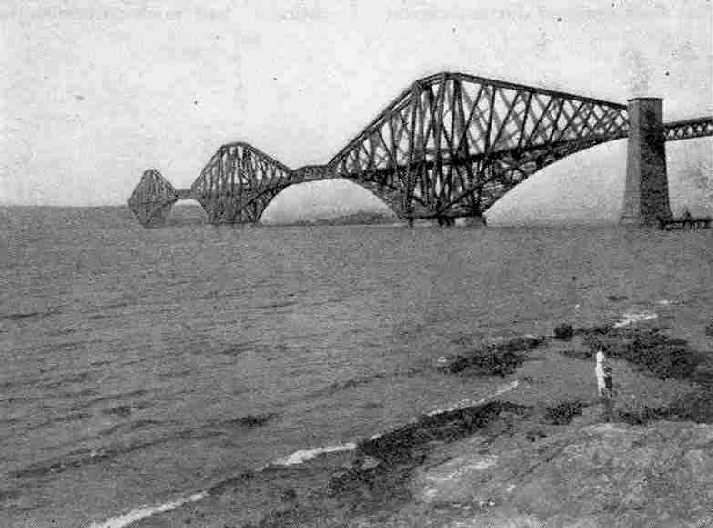

The Forth Bridge.

It is as we are travelling along the shores of the Forth, between Burntisland and Aberdour, that we first catch sight of the Forth Bridge. As we toil up the 1 in 70 from Inverkeithing, through rock cuttings and tunnels, we lose it again, until suddenly we are ushered on to the great structure, at a speed, probably, of not more than 20 m.p.h, at North Queensferry. Volumes might be written of this amazing bridge, which still, we are proud to remember, holds its head high among the engineering wonders of the world. The lessons of the Tay Bridge disaster were not lost on the engineers, for after that the Forth Bridge designs were completely altered in order to make adequate allowance for the effects of wind pressure. Seven years from 1883 to 1890, were occupied in the colossal task of its execution.

The total length of the Forth Bridge, including approach viaducts, is 1½ miles, and there is only one greater span in the world (in 1928) – the 1,800 ft of the Quebec Bridge across the St. Lawrence River in Canada – than the two 1,710 ft spans of the Forth giant. In order to obtain a good idea of their length we may think of between 28 and 29 modern corridor coaches strung out in a line, which would suffice to reach from one side of each span to the other. As to height, the underside of each span is 157 ft above water level, and from the water to the top of the cantilever towers is 361 ft, or within 4 ft of the top of the cross on St. Paul’s Cathedral dome above the pavement. Some 54,000 tons of steel were worked into the Forth Bridge, with its foundations and approaches, held together by 6 ½ million rivets. Forty-

Slowly we run across the bridge, with its magnificent views, through Dalmeny, down the sharp dip to Turnhouse, with a final mile-

the Forth Bridge, which also exceed the still longer platform at York.

It is just ten minutes to eleven, and our engine or engines move off with the dining cars, after which the remainder of the train is pushed forward to join a portion that is standing waiting for us at the east end of the same platform, including a through sleeper and coach from Glasgow to London. A “Pacific” is now in charge of the train, and in charge of “Pacifics” we shall doubtless run through all the way from Edinburgh to King’s Cross. But we have been over the route before in the

“Flying Scotsman”, so that we are quite justified now in seeking our beds and over the perfect permanent way of the East Coast Route, in going soundly to sleep. It is quite likely that we shall be unconscious of all that is passing until the “Aberdonian” is rushing through the tunnels of outer London, and deposits us safely and punctually in King’s Cross terminus at 7.30 the next morning.

Thus ends a journey in which we have been carried through no fewer than 18 English and Scottish counties. If it were notable in no other respect, the bridges that are crossed by the train would make it remarkable, for these include the world famous bridges that cross the Firths of Tay and Forth; in addition to the famous Royal Border Bridge at Berwick and the magnificent King Edward VII Bridge that spans the Tyne.

Double-

You can read more on “The Flying Scotsman”, “The Great North Road of Steel” and “The Silver Jubilee” on this website.