RAILWAYS OF BRITAIN - 45

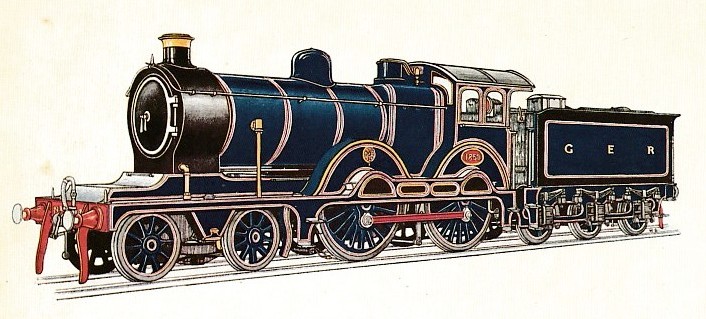

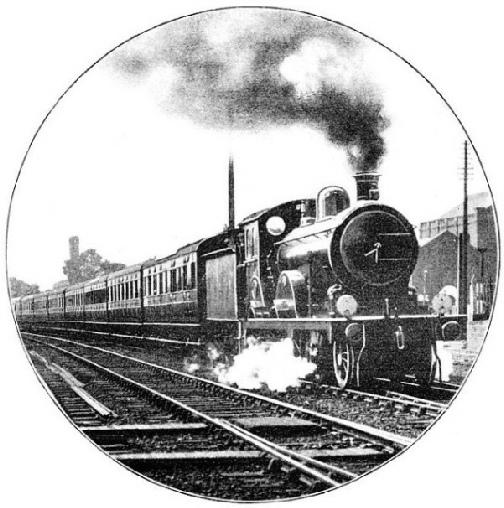

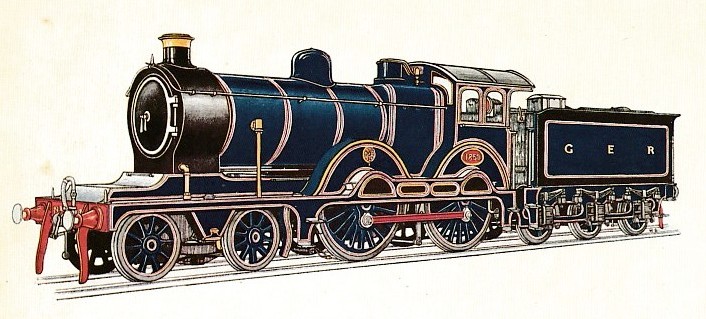

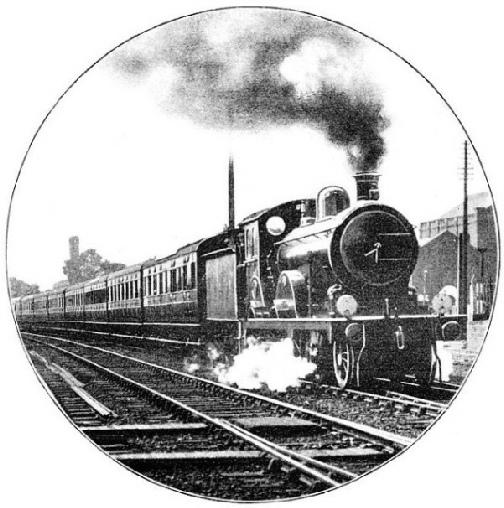

THE GREAT EASTERN RAILWAY EXPRESS PASSENGER LOCOMOTIVE, No. 1853

DESIGNED BY Mr J. HOLDEN, M.INST,C.E., M.INST.M.E.

THE Great Eastern is our greatest passenger line, for over 103 millions travel on it in a year, and it is the sixth in order of our great lines, the length being over 1200 miles, thus exceeding both the South Western and the Great Northern. “Friendly with all companies”, it was for years an example of a really well-managed concern that progressed without competition.

Through the greater part of its history, with the exception of the early parliamentary contests with the Great Northern, which ended in its being confined to that section of the country it was specially projected to serve, it was without any such “spur” as rivalry is assumed to give. Some years ago Sir George Gibb astonished an interviewer by telling him of the North Eastern, a line similarly placed, that “monopoly secures harmonious, consistent, and well-ordered progress”, and the Great Eastern, ever since the of the Marquess of Salisbury, afforded until recently another example of the truth of that doctrine. It is careful not to promise what it cannot perform, and, though not speedy in its fastest trains, its general average of speed for all trains is higher than that of any other company. Its suburban traffic is tremendous, and its goods traffic, 5½ million tons of it a year, is most miscellaneous.

The way it has fostered local produce and local industries is worthy of all praise. Think of the millions of herrings and trawl-fish it distributes from Yarmouth and its own docks at Lowestoft, the sprats from Aldeburgh, the shrimps - a thousand tons a year of them - from Harwich, the crabs from Cromer, the cockles from Wells, the oysters from Brightlingsea. Think of the grain and fruit and market-garden stuff it pours into London from all over its area. Think of the mustard and boots it scatters from Norwich, the chemicals from the marshes, the xylonite from Manningtree, the rifles from Enfield, the cordite from Waltham and Hadham, and the gun-cotton from Stowmarket. With the aid of the London & Blackwall it has a large dock and shipping business irrespective of what it may do at Parkeston, where it brings in almost everything from everywhere on the Continent. Add to this its passenger matters with the Broads and the towns of the east coast, the multitudes it runs to the Forest and the greater multitudes it carries in and out to business, and you will understand that it has quite enough upon its hands besides the sale of sea-water by the gallon for London’s baths.

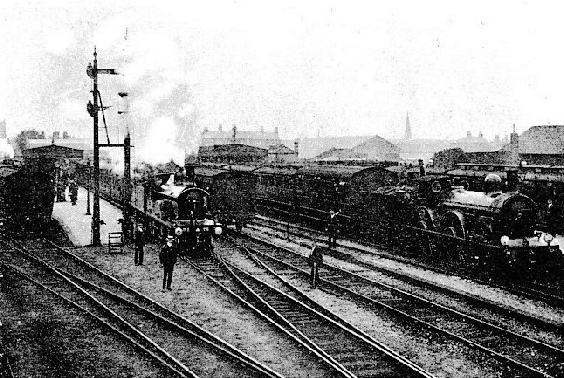

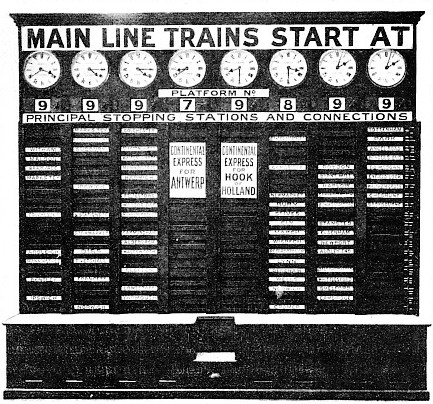

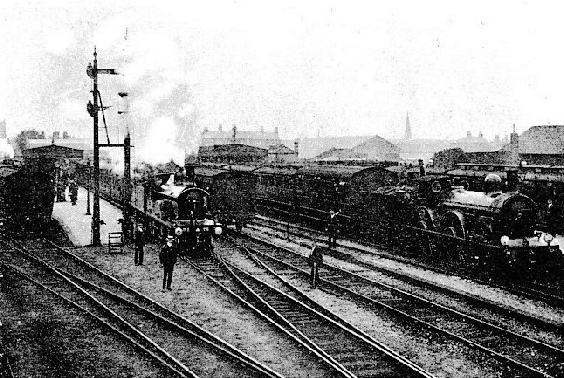

LIVERPOOL STREET STATION - MAIN LINE PLATFORMS

From Lowestoft to Huntingdon, from Shoreditch to Peterborough it has covered the east country between the Thames and the Wash with a network of rails having some forty loose ends, half of them ending on the coast, which has linked up every place of any importance and many that are of none; and north of that, through Spalding and Lincoln, it works right away to York and Chesterfield in search mainly of a coal trade that is ever increasing and now reaches 7½ millions of tons a year, obtained by its arrangements with the Great Central and Great Northern.

The ring of shields round London on its coat of arms tells you where it goes - Essex, Maldon, Ipswich, Norwich, Huntingdonshire, Cambridge, Hertford, Northamptonshire. By its close upon 1100 engines its passenger trains are run thirteen million miles and its goods trains eight millions of miles a year, and it has over 32,000 vehicles on its rails in addition to over a score of motor-cars, about 1300 horse-drawn carts, wagons, and omnibuses, and a fleet of fifteen steamers. In fact no one would imagine from the position in which its enterprising management has placed it that in 1867 it was in such low water that its creditors seized its engines for debt.

The Great Eastern is a railway with a past, in the usual acceptation of the term. From being nearly the worst of railways it has become one of the best. Those who have read about its territory in books know it as a flat country; those who have been there know that, with the exception of the north-western corner, it is anything but flat, being an undulating land with very little level in it. It was a tempting region for cheap railways laid practically on the natural lie of the ground, and thus it came about that the Great Eastern, which is an assemblage mainly of farmers’ lines, with many sharp curves and steep gradients, is really not an easy road to work.

MAIN LINE GOODS ENGINE, No. 1189

It began with the Eastern Counties, a 5-ft. line, which the Northern & Eastern, also a 5-ft. line, joined in 1844, three months before the change of gauge. Then there was the Norwich & Yarmouth which for years held the sprint record - one mile in 44 seconds - and was also the first to make trial of a telegraph system that showed the passage of the trains at its five chief stations, introduced on the opening day in 1844. It did not last long alone, for that year it joined with the Norwich & Brandon to become the Norfolk Railway; and four years afterwards the Norfolk joined with the Lowestoft to be worked by the Eastern Counties. Then there was the Eastern Union which amalgamated with the Ipswich & Bury and came to lease the Colchester, Stour Valley, Sudbury & Halstead, all of them falling into the net of the Eastern Counties in 1854. Into that net had also fallen the East Anglian, an amalgamation of the Lynn & Ely, the Lynn & Dereham, and the Ely & Huntingdon. The Newmarket, the Wells & Fakenham, and the East Suffolk followed suit; and - but we may got lost among the details, and enough has been said to show how the Great Eastern, which took the name in 1862, has been built up.

The engineer of the Eastern Counties was John Braithwaite, who, in partnership with Ericsson, built the Novelty for the Rainhill race, the engine for John Ross’s Victory, and much other machinery that failed, sometimes from no fault of its own, as, for instance, the first steam fire-engine, which the mob smashed up. In short, his experiences were not encouraging, and in 1834 he took to civil engineering, an offer having been made him to survey for a new railway in Essex in conjunction with Vignoles.

Vignoles did nearly all the work, though he took little part in the affairs of the company after the Act was obtained in 1836, five years after the project had been launched, when Braithwaite was left to go ahead alone. The line was to run from High Street, Shoreditch, by Colchester, to Norwich and Yarmouth, the longest line up to then projected, its length being 126 miles. Under another Act the Northern & Eastern was to start from a junction with it at Angel Lane, Stratford, and proceed to Bishop’s Stortford; and this company was fortunate, for the only difficult section was that between Shoreditch and Stratford.

Here Braithwaite had many calls on his peculiar gift for making the best of things. The marshes were for a time insatiable; they swallowed up all the materials dumped on them to form the embankment, and when at last the embankment ceased to sink into the ground it simply spread and would not hold together. As time was getting on, Braithwaite decided to treble the rate of accumulation, and built a staging in advance from which the wagons could be tipped side by side. This brought up the earthwork quickly enough round the stage, but the posts could not be readily moved to take the stage on farther. And he left them where they were and their lower framework with them, and went on building stage after stage in a manner new but now familiar, leaving the piles as he went, and there they are still, ensuring the permanence of the embankment. To drive these piles he was the first to use the American locomotive steam pile-driving machine, just as he was the first to introduce the American excavator to make his cuttings with.

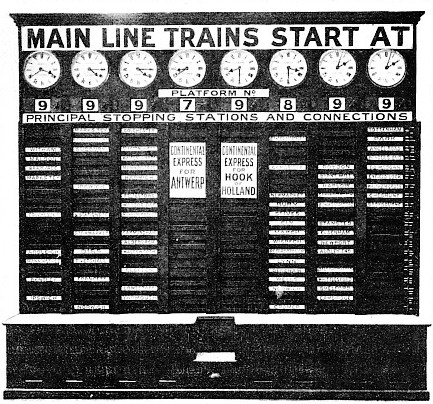

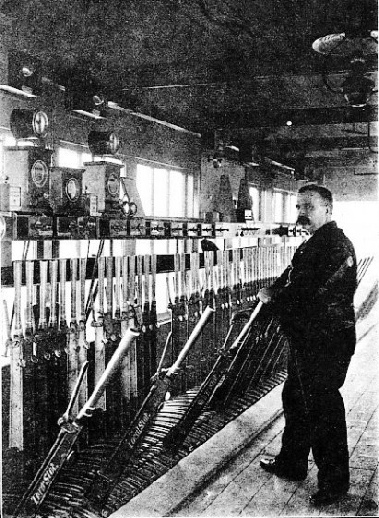

THE TRAIN INDICATOR AT LIVERPOOL STREET

Braithwaite had no conception of the magnitude of the work he was beginning; he was the narrowest in vision of all these engineers. He laid out the line to a 5-ft. gauge, and was the first witness called by the Gauge Commission. “Having adopted a wider gauge than others”, he said, “an impression has been created that I am a Broad Gauge man, but I state most distinctly that I am not a Broad Gauge man and I see no necessity for the Broad Gauge”. And then listen to this: “If the object were that all the world might leave London in the morning and come back at night, you would want magnificent gradients such as on the Great Western with the Broad Gauge”. O Shade of Braithwaite! Meet us at Liverpool Street on Saturday afternoon!

His directors wanted the 7-ft. gauge, and he reported against it and persuaded them to adopt this little gauge of his own. But why 5 ft. instead of 4 ft. 8½-in? This is his answer verbatim: “With a little more space between the tubes we should have a more quiet action of the water in the boiler and consequently less ebullition; and therefore with my diagram and my section of my engine, I added to all its different bearings, and I added what I considered sufficient additional space to the tubes, the sum of which gave me 4 ft. 11¾-in, and upon that I assumed that 5 ft. would be about the thing”.

With this in mind let us refer to the first engines that were placed on this 5-ft. line. They were designed by Braithwaite, and were the engines he speaks of. There were six of them, the four first to be delivered had 12-in by 18-in cylinders, the other two had 13-in by 18-in cylinders, otherwise they were all alike; they had four wheels, the leaders being 54-in and the drivers 72-in; the heating surface was 428 sq. ft; the boiler had 84 tubes of 1⅞-in, and its diameter, with the additional space for the less ebullition, etc., was 3 ft. 3-in. Thus the greater room he obtained by his 5-ft. gauge enabled him to produce a boiler of less diameter than that of the Rocket! And that is all that need be said about Braithwaite; except that the line he laid had to be taken up and replaced, eighty-four miles of it, at a cost of £1000 a mile, and that he ceased to have anything to do with the company after May 1843.

Shoreditch, that is Bishopsgate as we now know it, was the original terminus, but, owing to the station not being ready, the Eastern Counties was opened on Waterloo Day 1839 from Devonshire Street. Liverpool Street was not opened until the 2nd of February 1874, and then only for local trains, the terminus not getting into full swing until the 1st of the following November. This magnificent station, which cost over two millions of money, covers over sixteen acres and has over two miles of platform faces.

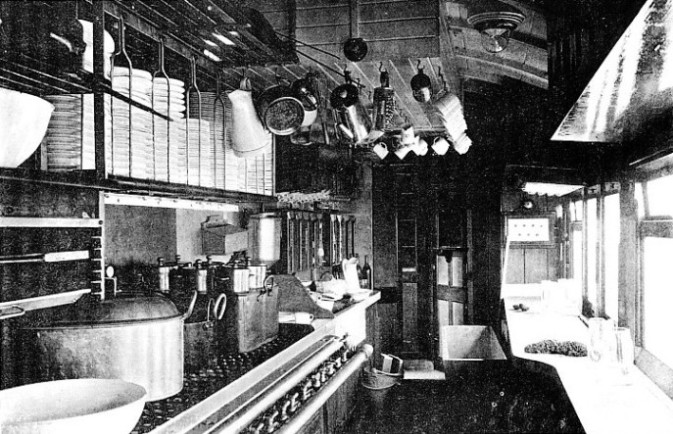

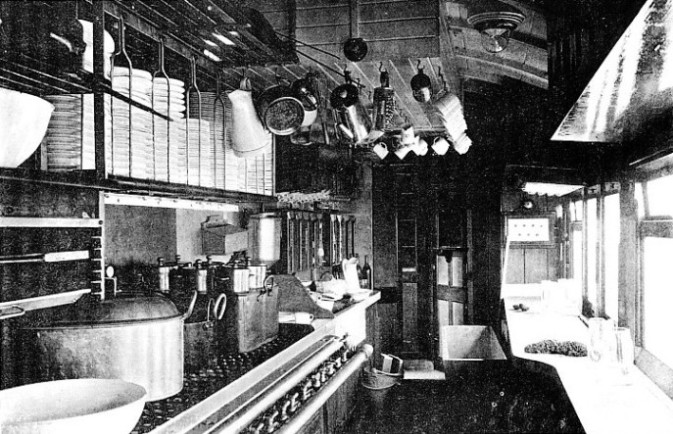

THE KITCHEN CAR OF THE NORFOLK COAST EXPRESS

The local traffic north and east is so varied and abounding that the main-line trains, are not clear of suburban troubles until they are beyond Tottenham and Romford. Up to Bethnal Green the road rises for nearly half a mile at a gradient of 1 in 71. Along the Colchester line, the original track, it rises gently until for the last three miles to Brentwood the gradient is 1 in 95, then it falls to Colchester and undulates at from 1 in 100 to 1 in 150 all the way to Yarmouth. Along the Cambridge line, the old Northern & Eastern, most of which was made by Morton Peto, it rises to Elsenham, the last five miles being at 1 in 130, and then it drops at 1 in 230 practically all the way to Cambridge, north of which it is level. Elsenham used to be the summit level of the system, but that height, 340 ft, is now reached between Epping and North Weald on the road to Ongar. Up in the- Fenland about March the Great Eastern has the flattest, dreariest district known to the railway traveller, a country in which the waterways are parallel straight lines and the marshes lead up without even a hillock right away to the unbroken horizon, a scene so deadly dull that it is impossible to read and the passenger takes to whittling sticks.

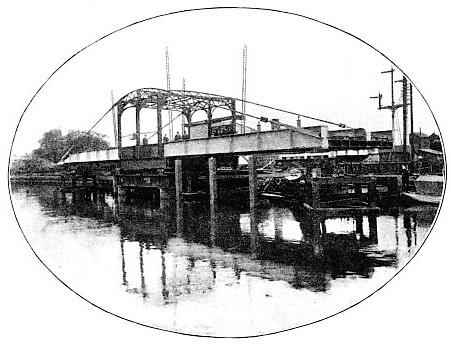

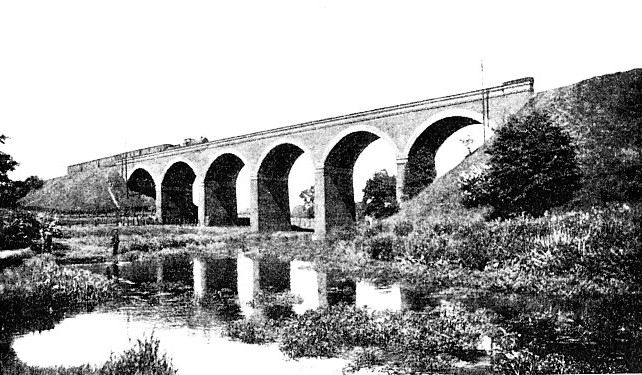

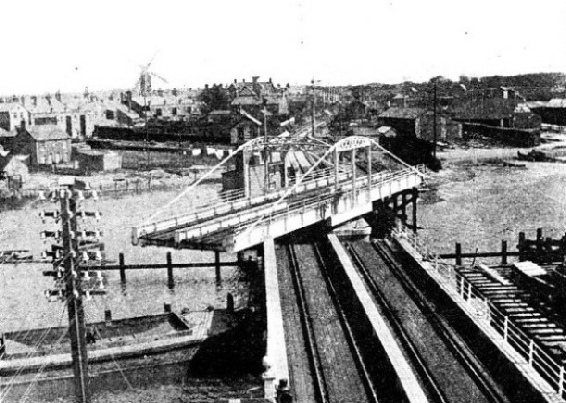

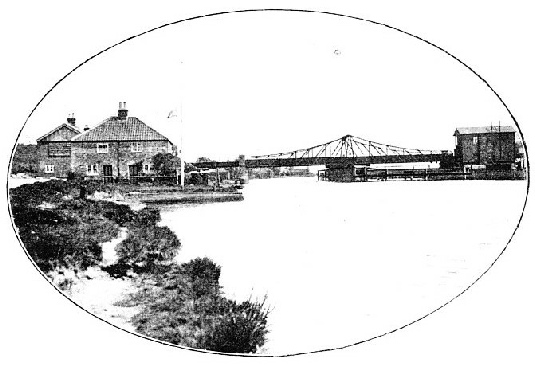

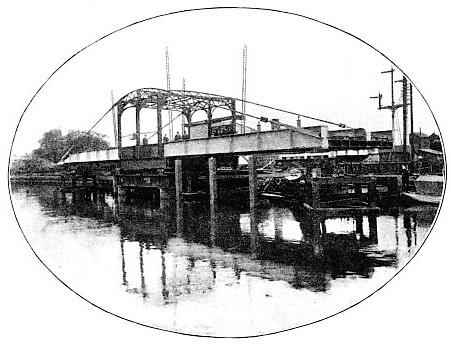

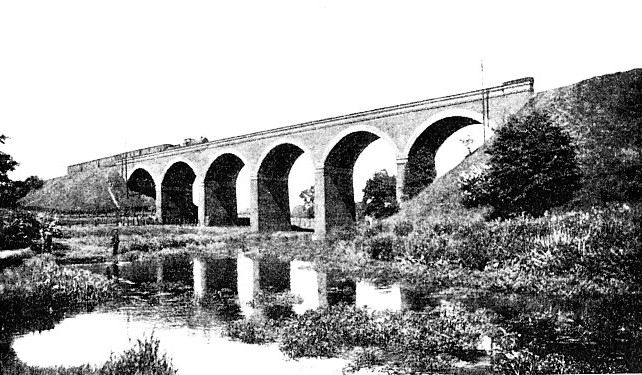

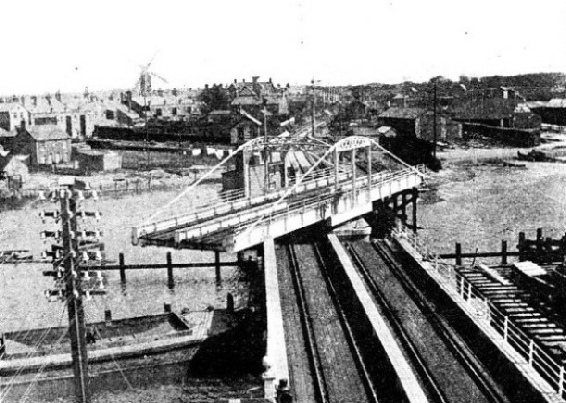

The longest tunnel, for the Great Eastern has tunnels, is between Newmarket and Warren Hill; the most interesting viaduct is that at Lakenham, between Swainsthorpe and Norwich, which was built in 1848 and carries the old Eastern Union over the River Yare and the Cambridge line. For the illustrations of this and of the Trowse and Reedham swing bridges we are indebted to the courtesy of the engineer, who tells us that “the Trowse Swing Bridge over the River Wensum between Trowse and Norwich was rebuilt in 1905. There are two viaduct spans of 24 ft. each. The swing portion is equal-armed and 121 ft. over all, crossing a 45-ft. span on each side of the centre, only one of which is navigable. The bridge is worked electrically from a cabin at the centre, and the wedging blocks at each end are released by hydraulic jacks worked direct from a pump coupled to an electric motor. Reedham Swing Bridge over the River Yare between Reedham and Haddiscoe was rebuilt in 1904. There are three viaduct spans of 33 ft. 6-in and two of 27 ft. 6-in. The swing portion is equal-armed and 141 ft. over all, crossing a 55-ft. span on each side of the centre, only one of which is navigable. The bridge is worked electrically from the cabin seen on the right in the photograph, and the wedging blocks on the centre pier are released by hydraulic jacks worked direct from a pump in the cabin.” These bridges and the two at Carlton Colville and Somerleyton, which so frequently block the way, are perhaps the most interesting features in the civil engineering work on the Great Eastern.

GREAT EASTERN RAILWAY COAT OF ARMS

Lakenham is of course a little thing compared with the roads on arches in the London district. There is one of these, nearly two miles long, from Stepney to Bow that cost a quarter of a million, and remained in the wilderness for years owing to the Eastern Counties declining to lay the junction rails. This belongs to the London & Blackwall, which was built mainly on arches and began as no other railway began. It was Rennie’s original scheme for putting London into communication with the eastern counties, the idea being to connect the City with the docks and continue the line as a grand trunk route through East Anglia. The great scheme failed to secure support, while the Eastern Counties obtained the Act for their line which left the docks for another company to deal with. Then Rennie, cutting off his continuation, formed a company for a line from Blackwall only to Fenchurch Street, to be worked by locomotives; and some one in the City seeing its importance secured Robert Stephenson as the engineer of an opposition line to be worked by ropes. A Bill for each was introduced into Parliament, and Rennie’s passed while Stephenson’s did not; but Rennie’s people could not raise enough money and Stephenson’s could, and so Stephenson’s London & Blackwall company bought up Rennie’s Commercial, and Stephenson became the engineer of the line that was made.

THE TROWSE SWING BRIDGE, NEAR NORWICH

As it was mentioned in the Act, which was obtained in 1836, he had to adopt a gauge of 5 ft. 0½-in, another of Rennie’s trivial variations, and the line was so short that he thought it would not pay to use locomotives. It measured 3½ miles, and was worked by two endless ropes, one for the up line, one for the down, some fourteen miles of rope in all. The working was on the slip principle, the two front coaches going through, the third slipping off at Poplar as did one for every station, the last being for Shadwell, the first station of the seven on the road. On the up journey the coaches were each pinned on at the same time, so that they came into Fenchurch Street separately with the same intervals between them as there were between the stations, all but the Blackwall pair which arrived together. Really an ingenious and remarkable railway, the only one on which the train started from every station at the same time; and on it was used Cooke & Wheatstone’s new galvanic telegraph. Needless to say the ropes wore out and were abandoned for locomotives; the stationary engines were removed to the City Flour Mills near Blackfriars Bridge; and the line - opened in 1840 - which soon became the dirtiest in the south of England, ended its separate existence in 1865 when the Great Eastern took it over, and thus obtained a second London terminus, the right to run into St. Pancras making a third.

Slipping the end carriage or carriages, not, however, in Blackwall style, is still practised, though not to the same extent as formerly; and the Great Eastern has more slips than any other line except the Great Western, which has more than double as many. In the old separate brake days there was no trouble about this slipping, but when the continuous brakes came in there were difficulties concerning the brake-hose, which put it out of fashion until the needful invention got a chance.

The slipping apparatus consists of a hinged hook which opens by the withdrawal of a pin or some other obvious device. Before it is put into action, the valve in the air-pipe is turned off by the guard in the carriage that is to be detached, either by pulling a cord or by reaching his arm out of the window, the uncoupling of the carriage and the shutting of the valve being sometimes worked pneumatically. The communication being cut off, the slip-carriage becomes a self-contained unit with a small supply of brake-power of its own in addition to that afforded by the hand brake.

LAKENHAM VIADUCT

When the carriage is to be slipped the train is checked in speed slightly, so as to relieve the couplings a little, and on the communication being severed the train increases in speed so as to get out of the way as soon as possible. The distance from the station at which the carriage is set free depends upon the speed, the gradient, and the slipperiness of the rail, which is dependent on the weather. One frosty day, for instance, when snow lay deep on the ground, the writer was in a slip for Luton which travelled through that station half the way to Leagrave, and had to be pushed back ingloriously by hand.

It is as well to be cautious in getting into last carriages, lest they should be slips. At St. Pancras on a Nottingham race-day, when the same slip was full, a corpulent racing-man, notwithstanding protest, forced his way in at the last moment, and stood making remarks intended to be irritating until the carriage stopped at Luton and the other passengers left him alone. “All change here!” said the guard; and when the bookmaker stepped out on to the platform and found the carriage alone in its glory, and the train disappearing in the distance, his look of surprise and disgust - and his language - amply repaid us for our unpleasant journey. Nowadays any number of trailers up to eight are slipped, so that there are not only slip carriages but slip trains, and slips are fitted with pneumatic horns as if they were motor-cars, the horns being worked by the feet; and there are head-lights and tail-lights for safety purposes, just as for an ordinary train.

Some sixty years ago the old Blackwall and the Eastern Counties joined together in forming the London, Tilbury, & Southend, which was opened in 1854, and after being run by the contractors for twenty-one years, mustered up courage enough in 1875 to undertake its own working. Since then have come Tilbury Docks and other developments, and a promising future.

Londonwards, the Tilbury’s own line ends at Gas Factory junction, continued jointly with the Metropolitan District to Whitechapel. By running powers it reaches Fenchurch Street, and, by a branch from Barking, it has its own metals to Woodgrange Park or thereabouts, whence by Forest Gate it runs into Liverpool Street, and, by the Tottenham & Forest Gate, St. Pancras. From Barking its main line goes straight to Shoeburyness through Southend, giving off a branch to Romford at Upminster. whence another goes south to join the old line that, through Rainham arid Purfleet, reaches Tilbury, and so continues to Pitsea on the main line, throwing off a branch half-way at Stanford-le-Hope to Thames Haven, which is nothing like so important a place as at one time it promised to be.

THE NORFOLK COAST EXPRESS APPROACHING BRENTWOOD

This company has 79 miles of track, on which in a year it carries 300,000 first-class passengers, and nearly 29 millions of third-class, besides dealing with, say, a million tons of minerals and merchandise. Its carriages are of varnished teak, and its engines were green or black until it recently ventured on a new departure by painting its new ones a neat, light grey that is at any rate smart and distinctive while it is fresh, and is quakerish enough to have been appropriate on the Stockton & Darlington.

It is the smallest of the railways using three London terminal stations, but it is not the shortest railway by any means. There are many much less in length, the shortest in the kingdom being the Deptford that belongs to the London Corporation, and measures 484 yards, the gross revenue of which is £10 per annum.

It is by running powers on the London, Tilbury, & Southend that the Great Eastern gets from Forest Gate to Barking. By the same means on the Midland it runs from Highgate Road into St. Pancras; and on the Midland & Great Northern Joint - one of the lines on which the engines are painted yellow - it works in the north-east corner of Norfolk to Sheringham. Croydon it reaches by way of the East London and Brighton. By its joint line with the Great Northern from March it goes south to Ramsey and Huntingdon, and north through Spalding, Sleaford, Lincoln, and Gainsborough, then, by a short stretch of the Great Northern, on to the joint again to Doncaster, and thence by running powers over the Great Northern and North Eastern its trains reach York. You will find its through carriages at Rugby, Coventry, Birmingham, Wakefield, Sheffield, Manchester, Warrington, and Liverpool, putting these towns in communication with Parkeston - whence the boats ply to the Hook of Holland, Antwerp, Hamburg, and Esbjerg - or with Norwich, Yarmouth, and Lowestoft.

In addition to the Yarmouth trade, and its docks at Lowestoft and quays at the mouth of the Orwell, it has extensive accommodation in the Thames district. At Canning Town on Bow Creek it has a big lighterage business, at Poplar there is the Blackwall Pepper Warehouse, dealing mainly with grain and farming sundries, just as Devonshire Street concerns itself with hay and straw and coals. Bishopsgate has five acres of warehouse floor space, and Goodman’s Yard almost as many; and then there is Spitalfields, devoting itself largely to eggs and flour. At Stratford the company has a little Covent Garden, and at Tufnell Park a sort of minor Deptford for the Islington cattle market close by. At Whitechapel it has its coal headquarters, whence it sends the coal trains, as well as the eight trains per day of vegetables and other commodities, by a 40-ton truck hoist taking two trucks at a time, through the Thames Tunnel on East London metals to New Cross for distribution in the south. For quick collection, rapid despatch, and early delivery it ranks with the best. Once, for example, it brought up during the night 950 tons of green peas in 300 trucks, and delivered them throughout London before nine o’clock next morning.

FIRST-CLASS DINING SALOON ON THE CROMER EXPRESS

This sort of thing is not so easy on the Great Eastern as other lines, for ever since the 21st of June 1897 it has been running passenger trains in and out of Liverpool Street all through the night, its booking offices never closing; and in the early morning it has to deal with the workmen’s rush to town in the overcrowded carriages we hear of. This overcrowding, however, is not so much due to the lack of facilities provided by the company as to the desire of passengers to travel by particular trains and in particular carriages - the first they reach or those that pull up nearest the exits - and, so far as the last trains are concerned, to the crowd who are not workmen but take advantage of coming cheaply to business though they may have to wait about the City until their office opens.

The profitable working of trains is not so simple as it may seem. Any person can run a train from one place to another when the road is clear, but the difficulty is to get it back again fairly well filled. There is nothing more wasteful than an empty train or a train kept idle for hours, with so many carriages, and the engine, as it were in quarantine.

The ideal manager is he who can keep his rolling stock on the move earning money all day long. So many coaches he has to deal with, and none of these mast he hang up doing nothing if he can help it. Further, he must fill every seat if he can, but have no passengers standing. On an electric line it really does not matter to him whether the coaches be overcrowded or not, for the power with which he hauls them comes from the central station, and it makes no difference if the load be in one train or half a dozen; but on a line worked by steam it is to his interest to prevent overcrowding, as it increases the weight of the train and throws more work on to the engine than he has provided for, while the other trains that run light require a less powerful engine. The carrying capacity of trains is limited by the length of the platforms and the length of the sidings, just as the length of the wheel-base of the coaches is regulated by the length of the locking-bar; and if more than one train is necessary to carry the passengers it is ridiculous to blame the company because the passengers insist on going by the last.

No account of the Great Eastern, however brief, would be complete without some reference to the twopenny fare question. By their Act of 1864, authorising the extension of their metropolitan lines, they are compelled to carry workmen at twopence for the return journey from Edmonton and Walthamstow. Now Edmonton is 8¾ miles from Liverpool Street and Walthamstow is 7, and the obligation means a journey of 17½ miles or 14 miles respectively for the couple of pence. The railway journey costing so little, there is nothing to wonder at in the acres of small dwellings that have overspread those once quiet rural retreats.

LYNN STATION

There was a time when these twopenny trains paid their expenses without adequate return on the capital spent on the lines over which they run. Then by the increase of the traffic and the consequent increase in the capital, due to the enlargements needed for the safe working of the greater number of trains, the return on the capital became less; and then the rise in working expenses wiped this out altogether, so that in 1899 the receipts equalled the working expenses and left nothing over. Soon the working began to cost more than the receipts, and as that cost of working has increased the loss has become so great as to more than counterbalance the profit made on the ordinary traffic.

The cost of working a railway is not the same all over the system. In the neighbourhood of large towns it is always greater than in the country districts, and in the suburbs of London it is much greater than elsewhere, owing to the short sections, the shorter hours of labour, the higher rates of pay, the heavy train loads and frequent stoppages, the short mileage worked by enginemen, the greater cost of coal in London, the heavier rating, and the larger number of stations on the line.

The exact proportion of the additional cost thus incurred was very carefully investigated by the Great Eastern Company in 1903, and these investigations proved that the cost of working in their London district was at least 21·12 per cent, higher than the average of the whole line; in addition to which there are other factors impossible to estimate, which bring the actual cost of working still higher. This figure was submitted in evidence to the Royal Commission on London Traffic and to the Select Committee on Workmen’s Trains, and its accuracy has not been questioned. In the Board of Trade report on London Traffic for 1907 the actual cost for working is put as at least 3s. 10·2d. per train mile, and if we set against it the 2s. 10·6d. per train mile, which is what the receipts amount to, we can quite understand why the Great Eastern wants no more twopenny workmen’s fares, which some people are so anxious to burden them with. The policy that forces a company to carry passengers at an unprofitable fare, and then raises the rates and otherwise adds to the expenses to increase the loss, must inevitably end in trouble, not only to the company but to the community, which gains nothing by the company’s ruin.

In regard to the London dock and riverside traffic, it has been said that the Great Eastern has a monopoly, a description which the company does not accept. It urges that as the North London has lines into Millwall and East and West India Docks, with running powers to other companies, and the Great Northern, London & North Western, and Midland have running powers over the Great Eastern, their lines in this district constitute not a monopoly but a public highway.

CARLTON COLVILLE SWING BRIDGE

At one time, prior to the advent of the Midland and Great Northern Joint lines into Norfolk, and the severe competition which has recently arisen in the London and suburban districts from electric trams and motor omnibuses, the Great Eastern system as a whole might have merited the title of a monopoly; although, serving as it does such a considerable extent of coast, it always has sea competition to meet. Still, it was formerly somewhat similarly situated to the North Eastern, which frankly accepts the description; and just as the Great Eastern has the Tilbury line in its south-eastern corner, so had the North Eastern the Hull & Barnsley until the recent agreement; and the North Eastern has the Lancashire & Yorkshire in its southwestern corner, answering in a similar way to the North London.

This, however, is comparing large things with small, for the Lancashire & Yorkshire is a great line, and the North London, which has become officially, as it has always been in reality, an extension of the North Western, is only 12 miles long. Originally it was The East and West India Docks and Birmingham Junction Railway, its object being to give the North Western access to the trade of the Thames, which the South Western had secured at Nine Elms and the Great Western had endeavoured to get at Vauxhall. Beginning in a small way, the minerals and merchandise business increased until by extensions the passenger traffic was developed to surpass it and became of such importance that goods trains had to cease from running during certain hours of the day; and now, owing to tram and other competition, passengers are falling off while goods are slowly growing. Short as the line is, it carries more than half a million passengers a week, and handles 1½ million tons of minerals and 1,768,000 tons of miscellaneous goods in the course of a year.

By minerals we mean mainly coals, and this reminds us of the enormous quantity stacked on the line at Stratford as a reserve, apparently in case of a strike or a break in the communications. The Great Eastern, however, has not a large coal-carrying business, though it has been trying to obtain one for years. Coal was the main cause of its wars with the Great Northern which ended in the peace of 1879, whereby the joint line to Black Carr junction was finally agreed upon.

Our railways carry about 400 million tons in a year, though only 2611 million tons are raised, which means that half the output is recorded twice. Of these the North Eastern carries 48 millions and the Great Eastern 7½, almost the same amount as that dealt with by the Alexandra line at Newport, which is only one of the South Wales group that carry some 50 million tons between them. In those parts the handling of coal for wagon loads and ship cargoes is a fine art. To see it at its best you must go to Newport, or Cardiff, or Penarth, or Barry. No tipping a ten-ton wagon down a ship’s hold in these days. There is a crane to every hold in the ship, and to the end of its chain is fixed a giant coal-scuttle. The scuttle is laid on a yielding platform in a pit in such a way that its mouth is fed from a short shoot just long enough to bridge the gap between it and the rail-end. The wagon runs up, kicks up behind, shoots its ten tons into the scuttle, which is hauled up and swung down into the vessel, where the conical bottom opens and spreads the coals around as gently as you would put them on the fire. But before it reaches the scuttle it has to be put into the truck at the collieries, and the way that is done is quite as ingenious as it is in South Yorkshire, Derbyshire, and Nottinghamshire, whence much of the coal comes that goes down the lift at Whitechapel.

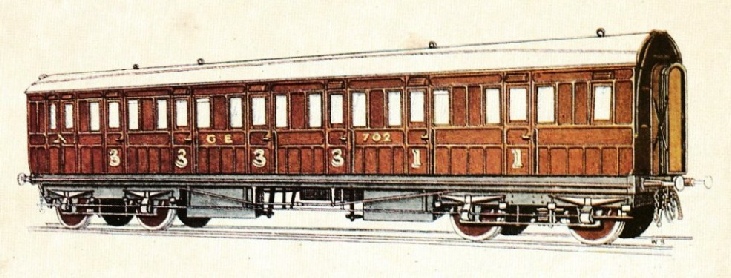

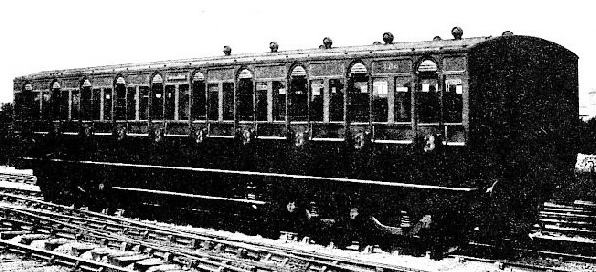

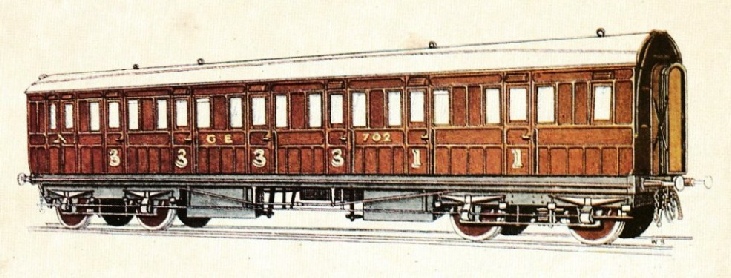

GREAT EASTERN RAILWAY COMPOSITE CARRIAGE, No. 702

Curiously enough, the 7½ million tons carried in every part of its territory by the Great Eastern is almost exactly the total quantity brought to London by all the railways put together, the rest of the 16 million tons consumed by the metropolis reaching it by sea or, in small quantities, by canal. That most London coal is sea-borne is something not generally known.

The first to wake up the Eastern Counties was George Hudson, who during his chairmanship effected many reforms, though unfortunately the railway king did not reign long enough. To him, of course, were due many of the amalgamations, for amalgamation was everywhere the keynote of his policy. He it was who founded the locomotive works at Stratford opened in 1848, Hudson’s Town as the place was called for years, which now cover 55 acres and give employment to some 5000 people.

Many notable engineers have been locomotive superintendents of the company. Following Braithwaite came William Fernihough - “the power of the engine is limited by the strength of the rail”, said he, and then after an interval came in 1850 the builder of the first engine at the works, John Viret Gooch. Then in 1856 came Robert Sinclair, the first of the Great Eastern men, followed by William Kitson in 1865, to be next year succeeded by S. W. Johnson who went to the Midland in 1873, when William Adams took over, to leave for the South Western in 1878. Then for three years followed Massey Bromley, to be followed in 1881 by T. Wilson Worsdell who went to the North Eastern in 1885, making room for James Holden who was succeeded by his son, S. D. Holden, in January 1908.

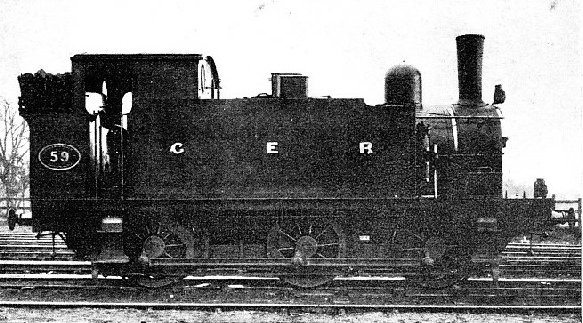

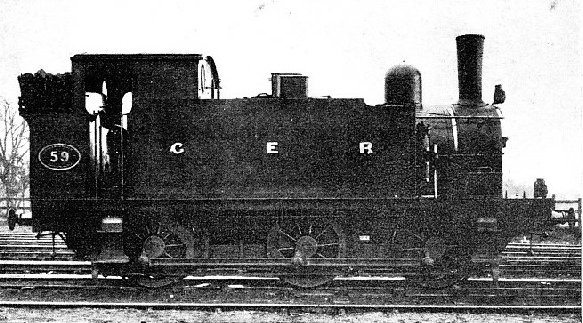

Some weird little engines were used by the independent companies, and the early Eastern Counties array was not much to be proud of; in fact it was not until Sinclair took the reins that anything not best forgotten was done. He brought out a class of singles noteworthy in their day - cylinders 16-in by 24-in, 87-in drivers, 45-in leaders and trailers, heating surface 958, weight 32 tons - which were built by Fairbairn and - of all people in the world for an English company - Schneider of Creuzot! Another well-known class of his was his 8-wheeled tanks, 2-4-2, cylinders 15-in by 22-in, coupled wheels 66-in, leaders and trailers 43-in, each pair carried on a Bissell truck so that the rigid wheel-base was only 6 ft; Further, the tanks of these engines were beneath the boiler and between the frames, and there was a cab that so pleased the enginemen that they presented the designer with a testimonial in which they greeted him as the inventor of the cab as applied to locomotives.

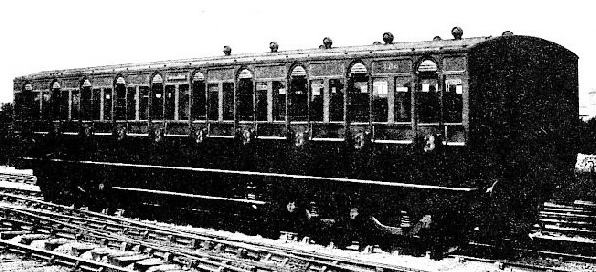

A NEW THIRD-CLASS CARRIAGE TO CARRY SIX A SIDE

Mr. Johnson’s first effort was a class of 4-4-0, with cylinders 17-in by 24-in, bogie wheels 43-in, coupled wheels 79-in, heating surface 1200, which began a new era. They were large engines, and the appearance of the turn-out was rather ridiculous owing to their being accompanied by the very small tenders with wooden frames which had been at work for years. This state of things, however, did not last long, and soon the Great Eastern engines became characterised by continuous improvement in power and appearance.

Mr. Adams followed, and carried on the improvement. Mr. Bromley is best remembered by his class of single expresses, some of which were built by Kitson and some by Dubs. They were 4-2-2’s, with cylinders 18-in by 24-in having valves on top worked by a rocking shaft, 90-in drivers, and a heating surface of 1226, the engine weighing 41 tons 13 cwt, and engine and tender 77 tons 12 cwt. More useful engines, however, were his bogie expresses of the 600 class, with cylinders 17½-in by 24-in, and 90-in. driving wheels, and his 0-4-2 tanks - and with regard to tank engines it may be as well to note that, though space does not admit of our saying much about them, they form half of the engine stock on some of our great lines, and in some cases work more than half of the fast passenger traffic.

The first of them was the Novelty already mentioned, carrying the water in a tank under the boiler and the coke in baskets on the platform. She might be described as a well-tank, though the present well-tanks carry the water in a tank beneath the footplate, side-tanks carrying it mainly in tanks on the frame plates over the driving wheels, and saddle-tanks having it on the top of the boiler. The Novelty, however, led nowhere, for the two engines “after her style”, as ordered for the Liverpool & Manchester - the William the Fourth and the Queen Adelaide - had 4-wheeled tenders pushed along in front of them, and the tank engine may be said to have begun with the Ariel’s Girdle on the Bentley and Hadleigh branch of the Eastern Union.

This famous little well-tank was in the 1851 Exhibition along with the Little England, “ designed,” as Robert Hunt said, “ with the same object, namely, of obtaining speed, safety, and economy in express and other quick traffic.” The Ariel’s Girdle was in 1856 transferred from the Eastern Union to the St. Ives branch of the Eastern Counties, on which in 1849 there was but one train a day, and owing to an increase of business in the first few months - which went no further - the service was doubled, the other train being a composite coach drawn by a horse. This mixed traffic of two trains per diem went on for six years, and it was to replace the horse that the Ariel’s Girdle was obtained. She was designed by Bridges Adams, and was a

4-wheeler with 5-ft drivers until, in 1868, she was altered to a 6-wheeler with four wheels coupled, the wheels measuring 4 ft, in which form she ended her days on the Millwall Extension in 1879.

A USEFUL LITTLE TANK ENGINE FOR SUBURBAN TRAFFIC

The rail-motor also began on the Great Eastern with Samuel’s Little Wonder, built as an inspection car for the officials, which was first used on the 23rd of October 1847 in a trip to Cambridge. In length 12 ft. 6-in, with the frames hung below the axles of the four 40-in wheels, her floor was only 9-in above the rails; and the two cylinders, one on each side of the vertical boiler, were 3½-in by 6-in. The boiler, 4 ft. 3-in in height and 19-in in diameter, had 35 tubes with a heating surface of 38 sq. ft, that of the circular firebox being 5½ sq. ft. She carried seven passengers, the water-tanks for 40 gallons being under the seats.

She weighed about a ton and a quarter, travelled at from thirty to over forty miles an hour, and was so successful as to lead on to the Enfield, designed by Bridges Adams for the Enfield branch. This was a 4-wheeled tank with a 4-wheeled carriage mounted together on the same frame. The front and hind wheels were flanged, but the 5-ft drivers and the pair of wheels behind them were without flanges. The six carrying wheels were a yard in diameter, the cylinders were 7-in by 12-in, and carried outside on the frame at the base of the smokebox, with the buffers just above them. The boiler, of the ordinary locomotive type, was 30-in in diameter, and double as long, and contained 115 tubes having a heating surface of 230 sq. ft, the firebox providing 255 sq. ft. The coach was a composite, with two first-class compartments in the middle and a second-class at each end. The height above rail-level was only 9-in, hence the placing of the buffer-beams on rising brackets. The branch becoming busy, two ordinary carriages were added, so as to form a short train, and the motor was also used for hauling the goods and coals. On a trial between Norwich and London the Enfield made the best record up to then, 126 miles in 3 hours 35 minutes; and on the 14th of July 1849, she replaced the ordinary engine on the 10 a.m. train from Shoreditch to Ely, and completed the journey in eight minutes under time.

The compound engine originated at Stratford with Nicholson & Samuel’s patent in 1850, and it had its second start in 1884 when Mr. Worsdell built No. 230, a 4-4-0 passenger engine with two inside cylinders, the high-pressure being 18-in and the low-pressure 26-in, the stroke being 24-in, the bogie wheels 37-in, coupled wheels 84-in, working pressure 160. This was followed by a 6-coupled goods engine, and, after a long series of trials, ten more compound passenger engines were built in 1885, the year that the inventor left for the North Eastern where the system was first introduced on a large scale.

Mr. James Holden during his long reign added largely to the blue brigade, and the black one too, and left them at a high pitch of excellence. One of his great achievements was the introduction of oil fuel. The company, having adopted oil-gas for lighting its carriages with, were turning the waste product into the waters of the Channelsea and the Lea when the sanitary authorities interfered, and means had to be discovered for getting rid of it elsewhere or utilising it. Mr. Holden resolved to try it as a substitute for coals in his engines. He led it from a tank in the tender by pipes to two injectors in the firebox plates some fourteen inches above the fire-bars, on which he kept a fire of small coal. To each injector he fitted two separate steam supplies, one for inducing and atomising the liquid fuel by a central jet, the other for supplying air to the atomised fuel by means of a ring of small jets around a blower placed near the nozzle. He thus ensured perfect combustion, and distributed the spray so well that no fire-brick was necessary, and he applied it so effectively that one ton of oil was equal in heating effect to twice the weight of steam coal; while the contrivance had the great advantage of allowing of coal being used at any time the supply of liquid fuel ran short.

THE GREAT BADDOW MOTOR-BUS

Petrolea was the first of the oil-burners, and so successful was that engine that the system was generally adopted. She was a 2-4-0, cylinders 18-in by 24-in, leading wheels 48-in, coupled wheels 84-in, heating surface 1230, her weight being 42 tons, that of the tender 32¼ tons, and the tender carried 500 gallons of oil. One of the later of the oil-burners is the Claud Hamilton, a 4-4-0, with cylinders 19-in by 26-in, bogie wheels 45-in, coupled wheels 84-in, heating surface 1630, pressure 180, boiler 4 ft. 9-in by 11 ft. 9-in, her 6-wheeled tender having 49-in wheels and carrying 2790 gallons of water and 715 gallons of oil. The newer engines have the Belpaire firebox, the first so fitted being No. 1850, which has a heating surface of 1706, and similar internal details to the Claud Hamilton. This similarity of parts is characteristic of the present Stratford system, the three largest classes of engines differing only in their wheels.

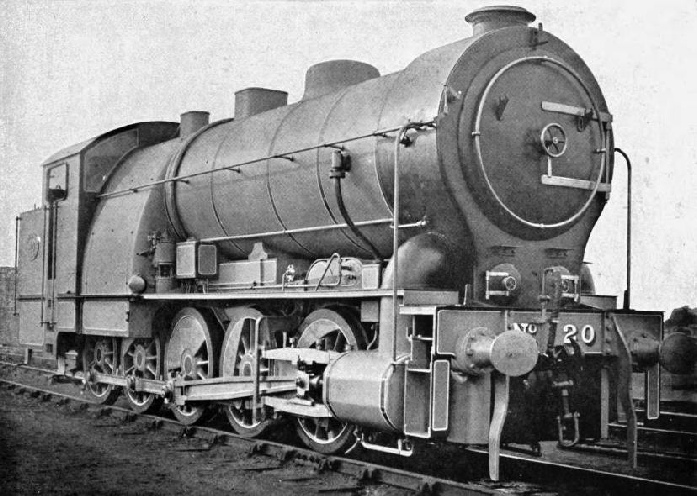

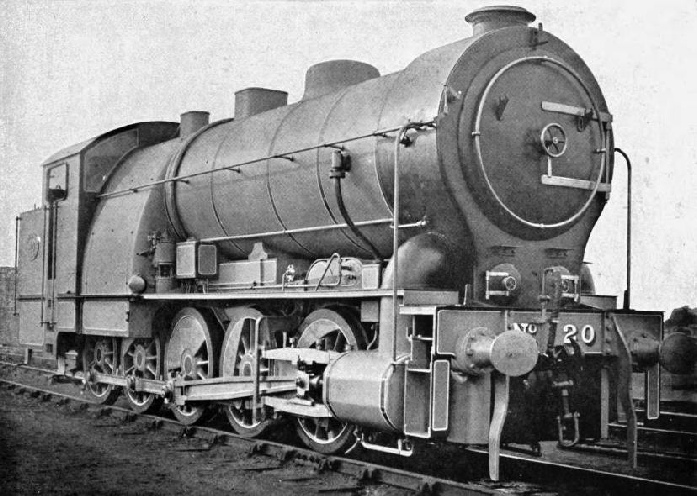

One engine which has been modified was of a class by itself. This was the 3-cylinder 10-coupled tank, known as the giant Decapod, built to show what steam could do in competing with electricity so far as starting quickly was concerned - an engine in fact that with a 315-ton train could start from a state of rest and in half a minute be travelling thirty miles an hour. It had ten 54-in wheels, the tyres of the middle pair being flangeless, as those of the old broad-gauge engines used to be. Two outside cylinders, each 18½-in by 24-in, drove on the middle pair of wheels, whilst a third cylinder of the same dimensions, placed between the frames, drove on the second pair. The boiler was 5 ft. 3-in in diameter and 15 ft. 10⅞-in between tube-plates, and the heating surface 3010 sq. ft. The Decapod would have done the work it was built to do, bad the permanent way and bridges been strong enough to carry it with safety, but the old bridges were designed to carry much lighter loads, and a great deal of money has been spent to strengthen the bridges to carry the heavier engines now in use on this line.

The Railway Engineers Association have now fixed a maximum load to be carried by the bridges of the future, thus adding an important link to the future standardisation of railways. Weight does not always mean power. There are engines a dozen tons lighter than others having the same heating surface, the same cylinder capacity, and the same tractive force, which are quite as powerful, the difference being only in the steam pressure, which means a general increase in dimensions, in boiler plates, crank axle, piston, connecting rod, and other things; and there is a great difference of opinion as to whether this extra pressure pays.

MR. JAMES HOLDEN’S “DECAPOD”, NO. 20

A goods engine can be heavier than a passenger engine because as a rule it is not worked at high speed, in fact for slow haulage the heavier it is the better, providing the track can stand it. Out in America, where crossings are level, goods engines are becoming gigantic. The Decapod would have been quite overshadowed, for instance, by the ponderous articulated Mallet, built for the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe - a double-engine single-boiler twenty-wheeler. Of this the sixteen drivers are coupled in two groups of eight each, and there is a two-wheeled pony truck at each end. The weight on the driving wheels is 22·7 tons per axle, that is 182 tons on them altogether. There are two high-pressure cylinders 25-in in diameter, and two low-pressure cylinders 39-in in diameter, the stroke in both cases being 28-in. The boiler is 7 ft. in diameter and 34 ft. 6-in long. At a distance of 6 ft. 6-in from the firebox is a combustion chamber 4 ft. 6-in long, into which deliver 246 3-in tubes, and from which run to the smokebox 454 2¼-in tubes which are 23 ft. long. There is a superheater with vertical tubes in the combustion chamber. The firebox is 11½ ft. long and 9½ ft. wide outside. In fact there is good provision for working up to the 215 lb. per inch of her steam pressure, the grate area being 89 sq. ft. and the total heating surface 7839 sq. ft! But even this mighty machine has its limitations, for the heating surface is so large and the evaporation so great that a stop has to be made every five-and-twenty miles to fill up the tender.

Some of the Great Eastern engines are fitted with power reversing gear, actuated by the Westinghouse pump without interfering with its main duty, that of working the continuous brake. An engine to be of any practical use must be able to run either forwards or backwards, and it is reversed by admitting the steam to the other end of the cylinder first, whichever that other end may be. When the crank is at rest it will be moved round in one way by admitting the steam at the top, and the other way by admitting it at the bottom; and on the valve motion by which this is effected depends the control of the admission so that the steam can be worked expansively, that is cut off at any part of the stroke to ensure that the amount used is in proportion to the work required.

The control of the power is clearly the most important part of the engine, but it could only be satisfactorily explained by diagrams and is much too technical to be enlarged upon here. Let it suffice to say that at first engines were reversed by a loose excentric working on a forked lever which was in connection with the valve stem. When it was desired to reverse, the engine was stopped, the lever lifted out of gear, and the valves moved by hand till the excentric reached a position that gave the opposite motion and the fork again dropped into gear. When there were two cylinders there were two levers. This served the purpose at moderate speeds, but at high speed the levers were in danger of jumping out of gear. It was to remedy this that, in 1842, William Howe invented what is generally known as the Stephenson gear, in which each cylinder has a backward and forward motion excentric, with the rods connected by a curved slotted link adjustable by a shaft and lever.

The control of the power is clearly the most important part of the engine, but it could only be satisfactorily explained by diagrams and is much too technical to be enlarged upon here. Let it suffice to say that at first engines were reversed by a loose excentric working on a forked lever which was in connection with the valve stem. When it was desired to reverse, the engine was stopped, the lever lifted out of gear, and the valves moved by hand till the excentric reached a position that gave the opposite motion and the fork again dropped into gear. When there were two cylinders there were two levers. This served the purpose at moderate speeds, but at high speed the levers were in danger of jumping out of gear. It was to remedy this that, in 1842, William Howe invented what is generally known as the Stephenson gear, in which each cylinder has a backward and forward motion excentric, with the rods connected by a curved slotted link adjustable by a shaft and lever.

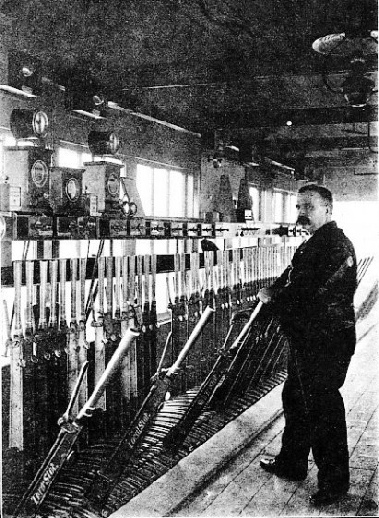

SIGNAL CABIN AT BETHNAL GREEN WEST JUNCTION

There had been over a dozen devices adopted and abandoned before this, and there have been quite as many since. Two years after Howe came Walschaerts with his first proposal, that made no progress until the one excentric gave place to the return crank in 1859, since when it has slowly worked its way into favour for its adaptability for steam chests above or below, its excellent distribution of steam, and its being so accessible when used with outside cylinders. In 1848 Daniel Gooch introduced his fixed link motion, in which the engine is reversed by raising or lowering the quadrant block in the slot, the block being connected with the valve stem by the radius rod. Then in 1855 Allan brought out his straight link actuated by two excentrics; and in 1879 came Joy with his linkages in which the number of working parts was reduced, the gearing made lighter, and the strains made central; excentrics being dispensed with and the movement obtained from the connecting rod. This gear is now much in favour owing to its economy in construction, the prolonged expansion given by it, as well as the high mean effective pressure it provides on the pistons, its only drawback being the wear of its pins and slides; and those who would appreciate its ingenuity can study it in the motion diagrams at South Kensington.

Great Eastern trains are long, though they are none of them so long as the Cambridge platform, which measures nearly a quarter of a mile; and they are heavy, particularly in the suburbs, where the coaches take six a side to deal with the crowds using workmen’s tickets that come to London in an hour or two every morning and leave it within a few hours every night; and the main-line trains are also heavy, such, for instance, as the Norfolk Coast express, a 317-ton train 638 ft. long, with its dozen vestibuled corridor cars, including its first and third restaurant cars and a kitchen car - quite a triumph of compactness and ingenuity - every one of which has its own electric light outfit run from a dynamo driven from its own axle. What may be called the travelling hotel business is excellently worked on the Great Eastern; not only does the company cater for your breakfast, luncheon, tea, and dinner, but it even adds a supper car to its theatre trains.

The Great Eastern time-tables, with their multitude of trains, occupy fifty pages of Bradshaw and fill them handsomely. Those who would know how our railways have grown can realise it most readily by comparing that indispensable monthly, containing over 900 pages, with a copy of earlier date. Few who consult it are aware that it originated in the map which is generally treated with such scant courtesy.

A SIGNAL GANTRY AT STRATFORD

George Bradshaw, who was born at Windsor Bridge, Pendleton, in 1801, began life as an apprentice to an engraver. In 1830, when in business for himself as an engraver and printer, he issued, as canals were then flourishing, a map of inland navigation, the first of three which proved most useful to canal passengers. When railways were taking the place of canals he, in 1838, followed these three with his map of the railways of Great Britain; and on the 25th of October 1839 he started his Bradshaw’s Railway Time-Table and Assistant to Railway Travelling. This small 18mo of 24 pages, “published by the assistance of several railway companies”, became next year Bradshaw's Railway Companion, and contained several maps and a few tables that were kept up to date by time-sheets, monthly and otherwise, which appeared on whatever day of the month he could manage.

The publication soon became recognised as more or less official, and, in a short time, in response to Bradshaw’s repeated appeals, the railway companies, with a view of obliging him, agreed to begin alterations in their train service on the first of the month instead of on any day the idea occurred to them. If Bradshaw had done no more than this he would deserve remembrance.

Having assured himself of being regularly supplied with copy, he abandoned his old correction-sheets, and for December 1841 produced the first number of his famous Guide, which has appeared regularly ever since. It was heartily welcomed from the first, particularly by the railway people, and on account of it - strange to relate - he was elected an Associate of the Institution of Civil Engineers, in February 1842, out of gratitude for having done so much to help on railway enterprise.

His was not, however, the first railway guide nor the first combined guide. Prior to it there had been guides to the separate lines, and these were not only in book or pamphlet form, for some of them were medals to be carried in the pocket, with the stations and times, and in some cases the distances, given. The idea to which he owed his success was to treat the time-table as being made to be changed, and keeping abreast of the changes.

THE TRAIN BOARD

Time-tables appear to have begun as separate way-bills for each train, as used by the coaches and canal boats. The next step was to print two or three on each bill, and these being placed side by side, vertically or horizontally, gradually led to the columnar form which in so many varieties in sheet and pamphlet the companies have to prepare and use for their own purposes - and publish at a loss for the information of the public, who imagine there is a profit on the pennyworth or twopenny worth, as the case may be, whereas it only pays as an advertisement.

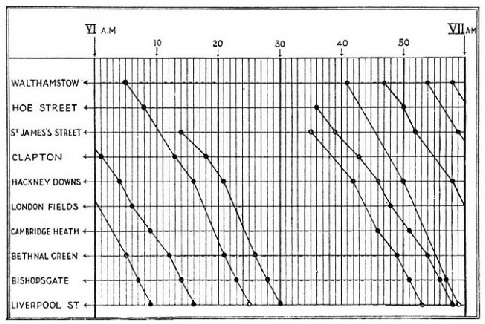

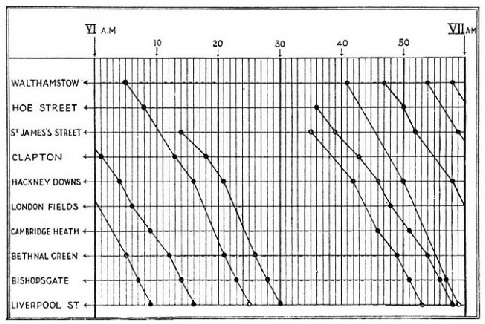

Diagrams are now being used in railway work wherever possible, and one of the first of the diagram methods to be introduced was that of stringing the trains, “the visualised time-table” as it has been called. In this a long board is divided vertically into twenty-four equal spaces, one for every hour of the day. Each of these hours is similarly divided into sixty minutes, the half-hour, quarter-hour, and five-minute intervals being marked with darker lines. The hour lines are marked from I. to XII., and I. to XII. again, so that by joining the outer edges, if it were a strip of paper, you would have a cylindrical clock-face, as in the automatic register of an aneroid barometer. This time-scale is divided horizontally into a distance scale, the stations and junctions being placed on the margin in their relative positions; and thereby you have a blank time-table, which you proceed to fill up not by writing figures but by sticking in pins.

As a specimen hour’s work let us take the up-trains from Walthamstow (Wood Street) between six and seven o’clock in the morning. The first train to come in is that leaving Chingford at 5.56, which reaches Walthamstow at 6.5. Where the 6.5 line on our chart crosses the Walthamstow horizontal line we drive in a pin; at Hoe Street at 6.8 we put in another pin; as the train runs through St. James’s Street our next pin goes in at Clapton at 6.13; three minutes afterwards comes a pin at Hackney Downs; then, passing London Fields and Cambridge Heath, we put in our next pin at 6.21 at Bethnal Green, the next at Bishopsgate at 6.23, and the last at Liverpool Street at 6.25. As we have plotted the 6.5, let us plot the 6.14 from St. James’s Street, the 6.35 also from there, the 6.36 from Hoe Street, the 6.41 from Walthamstow, and the 6.47, 6.54, and 6.58, none of which, except the 6.36, stop at all stations.

Now join up the pins, marking the progress of each train, by a piece of coloured thread, and you will see at a glance where every train ought to be on the line at any given moment. Use a different coloured thread for each sort of train, put in two pins for arrival and departure in cases where the train waits for another to pass it, and you have the up traffic of the line in that section graphically displayed; and with other pins and other threads you can run in the coal trains and goods trains and fish trains, or whatever they may be, and make your table as complicated as you need; but it will always show where changes can be safely effected, and other trains worked in, which is what the maker of time-tables wants to know.

Now join up the pins, marking the progress of each train, by a piece of coloured thread, and you will see at a glance where every train ought to be on the line at any given moment. Use a different coloured thread for each sort of train, put in two pins for arrival and departure in cases where the train waits for another to pass it, and you have the up traffic of the line in that section graphically displayed; and with other pins and other threads you can run in the coal trains and goods trains and fish trains, or whatever they may be, and make your table as complicated as you need; but it will always show where changes can be safely effected, and other trains worked in, which is what the maker of time-tables wants to know.

SEA WATER ARRIVING AT LIVERPOOL STREET FROM LOWESTOFT

His is no easy task, particularly in the spring and autumn when the chief alterations are made, tor then it is that the character of the traffic changes, goods being dominant in winter and passengers in summer. “No one”, as Findlay said, “who has ever glanced with an intelligent eye at the time-table of a great railway, will be surprised to learn that this operation is one of the most complicated nature, and involving great labour and considerable skill. This will be apparent if it be borne in mind that, supposing, for instance, a train running from London to Scotland is altered in its timing ever so slightly, it involves the necessity of altering all the trains running on branch lines in connection with it, and many other trains which are affected by it. A train service is, in fact, like a house of cards; if the bottom card be interfered with, the whole edifice is disarranged, and has to be built up afresh. Remembering all this, and the pressure under which the work must be done, the wonder is not so much that an occasional error creeps into a time-table as that such marvellous accuracy is, on the whole, arrived at”. And such errors, few as they were, have become much fever since the introduction of the train-board.

The book published by some companies at a penny, and by some at twopence, which you buy at a bookstall, or the booking-office, and find in every club and hotel, is not the chief time-table printed by the railway company, but quite a small thing compared with the working time-table used by the company’s men, which, on any of our great lines, forms a volume of three or four hundred pages, requiring much more alteration. This gives the running of every sort of train, passenger and goods, and even the empties, and in some cases the light engines on their way to and from work, the times at every station they stop at and run through, and the times of their waiting and shunting at every station and siding; and into it as insets go the leaflets issued in a hurry dealing with the excursions and specials arranged for during the month, and not known of when it went to press. Some of these way-bills, as they would have been called in the old days, are masses of detail, particularly that of the royal train, which forms quite a booklet of half a dozen closely-printed pages, giving the time of the train past every signal-box from one end of the journey to the other.

Reedham Swing bridge

Sandringham is on the Great Eastern - Wolferton being the nearest station;—the royal trains being generally worked not from Liverpool Street but from St. Pancras by way of Kentish Town and South Tottenham, though it sometimes happens that the train arrives on the company’s metals at some more distant junction. Of other short notice specials it has a fair share, but its ordinary work is not so broken in upon as on some lines. Excursions of all lengths it has many, to the coast, to the Broads - which is much the same thing up Norfolk way - and to almost everywhere on its system beginning with the Forest and radiating beyond; and of course it has its race-days, principally at Newmarket, where there are eight meetings a year, and a group of training stables meaning horses by train to the number of over 12,000 a year.

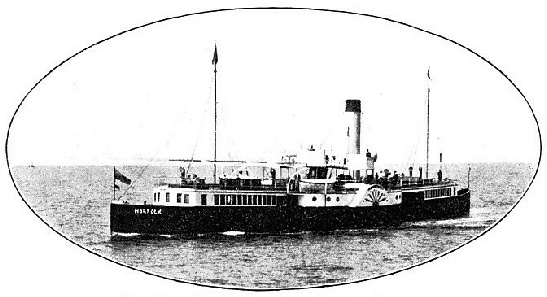

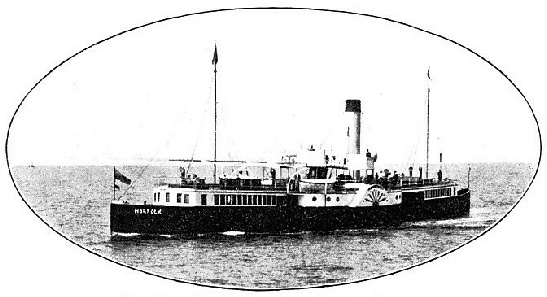

THE RIVER SERVICE FROM IPSWICH TO FELIXSTOWE

A more hopeless railway there never was when in 1867 Lord Cranborne, who the same year became Marquess of Salisbury, was implored to accept its chairmanship. By his reputation and conspicuous ability he gave it hope and restored its credit, and raised three millions to give it a fresh start, from which it has never looked back. In 1875 came the man to take advantage of the better prospects and make them better still. The one outstanding thing that crippled the company was its want of punctuality, and this he set to work vigorously to remedy. Such a tumult of growls against hustling and petty preciseness had not up till then been heard in the east, but Punctuality Parkes went on his way regardless of protest in clearing out the unpunctual, and drilling the staff into the belief that time-tables are not intended to be works of fiction but of fact. And he succeeded, and, loyally helped, he put the line on another plane of existence. He it was who abandoned Bishopsgate of evil memory and took the terminus to Liverpool Street; he it was who put the clock there that there could be no mistake as to what the time was at every station and in every man’s pocket. Parkeston, the Great Eastern port for the Continent, he also made, and it is named after him; and there you start by steamer for the Hook of Holland or elsewhere just as punctually as you do from London by train.

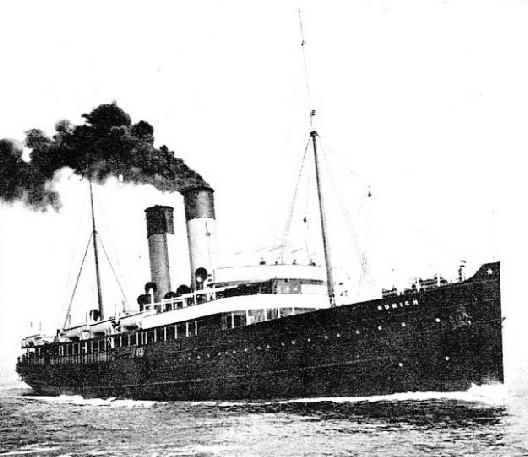

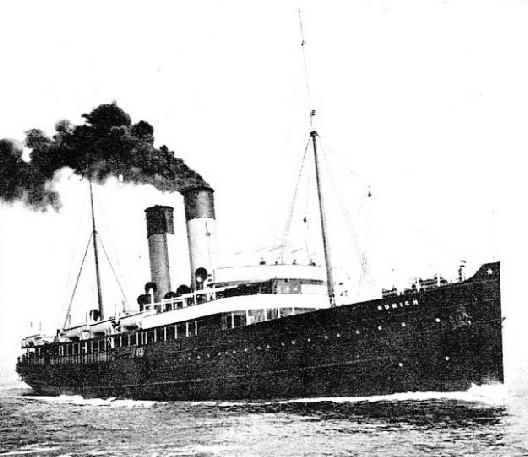

The Great Eastern Company’s fleet consists of 8 passenger boats, 4 cargo boats, and the 3 small paddle steamers that ply on the river between Ipswich, Harwich, and Felixstowe. Three of its Channel steamers are driven by turbines, the others being twin-screw boats of the old type. All the passenger steamers are fitted with wireless telegraphy and submarine signalling appliances, and are well-known examples of what may be called the liner type, with passenger accommodation of the best.

Great Eastern R.M. Steamer Munich - Harwich and Hook of Holland Service.

You can read more on “The Great Central Railway”, “The Hook of Holland Boat Express” and “The Romance of the LNER”.

The control of the power is clearly the most important part of the engine, but it could only be satisfactorily explained by diagrams and is much too technical to be enlarged upon here. Let it suffice to say that at first engines were reversed by a loose excentric working on a forked lever which was in connection with the valve stem. When it was desired to reverse, the engine was stopped, the lever lifted out of gear, and the valves moved by hand till the excentric reached a position that gave the opposite motion and the fork again dropped into gear. When there were two cylinders there were two levers. This served the purpose at moderate speeds, but at high speed the levers were in danger of jumping out of gear. It was to remedy this that, in 1842, William Howe invented what is generally known as the Stephenson gear, in which each cylinder has a backward and forward motion excentric, with the rods connected by a curved slotted link adjustable by a shaft and lever.

The control of the power is clearly the most important part of the engine, but it could only be satisfactorily explained by diagrams and is much too technical to be enlarged upon here. Let it suffice to say that at first engines were reversed by a loose excentric working on a forked lever which was in connection with the valve stem. When it was desired to reverse, the engine was stopped, the lever lifted out of gear, and the valves moved by hand till the excentric reached a position that gave the opposite motion and the fork again dropped into gear. When there were two cylinders there were two levers. This served the purpose at moderate speeds, but at high speed the levers were in danger of jumping out of gear. It was to remedy this that, in 1842, William Howe invented what is generally known as the Stephenson gear, in which each cylinder has a backward and forward motion excentric, with the rods connected by a curved slotted link adjustable by a shaft and lever.

Now join up the pins, marking the progress of each train, by a piece of coloured thread, and you will see at a glance where every train ought to be on the line at any given moment. Use a different coloured thread for each sort of train, put in two pins for arrival and departure in cases where the train waits for another to pass it, and you have the up traffic of the line in that section graphically displayed; and with other pins and other threads you can run in the coal trains and goods trains and fish trains, or whatever they may be, and make your table as complicated as you need; but it will always show where changes can be safely effected, and other trains worked in, which is what the maker of time-

Now join up the pins, marking the progress of each train, by a piece of coloured thread, and you will see at a glance where every train ought to be on the line at any given moment. Use a different coloured thread for each sort of train, put in two pins for arrival and departure in cases where the train waits for another to pass it, and you have the up traffic of the line in that section graphically displayed; and with other pins and other threads you can run in the coal trains and goods trains and fish trains, or whatever they may be, and make your table as complicated as you need; but it will always show where changes can be safely effected, and other trains worked in, which is what the maker of time-