© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

Through Desert and Jungle

Modernity That Disturbs the Silence of Age-

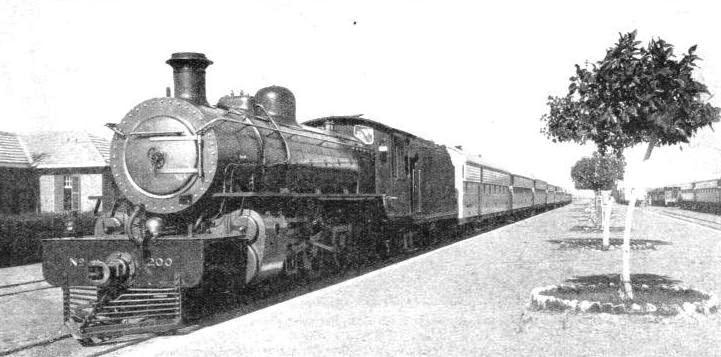

KHARTOUM STATION, with its wide platforms pleasantly laid out with trees, is a refreshing charts to the traveller after his 250-

THE Dark Continent is no longer dark: civilization has brought progress to Africa. In the valleys of the Upper Nile, past the temples of almost forgotten races, and through the deserts of East Africa, Sudan, Uganda and Kenya, the railway engine’s whistle disturbs the air. To travel by train and river steamer from Wadi Halfa, in Northern Sudan, to the port of Mombasa, in Kenya, is an unforgettable experience.

Wadi Halfa is the north gateway to Sudan. This town, the capital of the Halfa Province, has played an important part in the modern history of Sudan. In 1896 an expedition under Lord Kitchener fought its way south, while Wadi Halfa served as his base. The foundation of the present Sudan railway system was laid at Wadi Halfa. From it a military railway was originally constructed along the east bank of the Nile to Sarras, later to Akasha and then to Kerma, a navigable part of the Nile some 200 miles south of Wadi Halfa itself. This railway was ultimately abandoned.

Another military railway was begun on January 1, 1897, during the same campaign, and the track extended southwards over the desert to Abu Hamed and beyond to Khartoum. The line, 576 miles long, was the beginning of the Sudan system. This second line, which once carried reinforcements and supplies to the British troops, now forms part of the present Sudan railway to Atbara, and then on either to Port Sudan or Khartoum.

The gauges in Africa vary in dimension from the 4 ft 8½-

The journey south from Wadi Halfa is carried out in trains specially built to protect passengers from the heat of this torrid region, where sun-

From Wadi Halfa the train leaves the winding banks of the Nile and crosses the Nubian desert. For 250 miles there is nothing but vast stretches of sand, relieved only by rocks, until the train reaches Abu Hamed, on the Nile.

Here the landscape begins to change. Pleasant villages and strips of cultivated land glide past the window.

Two hundred miles from Khartoum, the capital of the Sudan, the train reaches Atbara, where the river Atbara joins the Nile. The town of Atbara forms a railway junction for an important line branching off to Port Sudan on the Red Sea.

Khartoum itself is a large town and, although built on the banks of the Nile, lies 1,200 ft above sea level. With its wide tree and grass-

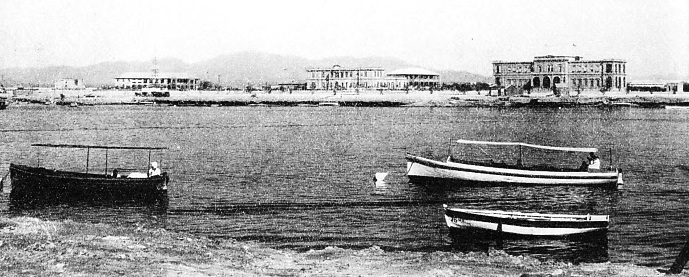

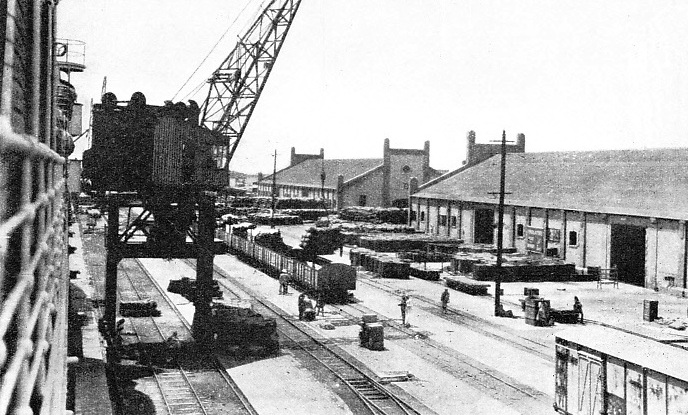

PORT SUDAN HARBOUR, the chief trade outlet of the Sudan on the Red Sea, is linked up with the interior by a main line to Atbara.

It is a city with many historic associations, and the Governor-

Khartoum possesses all the amenities of civilization. It has a racecourse, golf course, tennis courts and fine public buildings. Its railway station is both large and modern. But, to remind us that the desert is at hand, tropical shrubs grow along the side of the wide, uncovered platforms.

The work of the engineers in building a railway across desert country usually brings its own special problems, but the task of track maintenance through this desert often becomes a matter of extreme difficulty, as when a north-

Although the rainfall is often practically negligible for many years on end, the day comes when a cloudburst will suddenly occur and flood a whole section of the region. This means a “wash-

On from Khartoum the Sudan Railway runs for another 430 miles or so to Sennar Junction, near the famous Sennar Dam. At Sennar the main line turns sharply to the west and finally terminates at El Obeid. There is also another line running eastwards which passes over the Dam across the Blue Nile. This line then turns northwards and links up with the Atbara-

A traveller who wishes to reach Mombasa from Khartoum will take a train bound for Kosti. At Kosti he will then take a river steamer for Juba. Juba lies close to the borders of Kenya and Uganda, and is the southern gateway to Sudan.

Mombasa from Khartoum will take a train bound for Kosti. At Kosti he will then take a river steamer for Juba. Juba lies close to the borders of Kenya and Uganda, and is the southern gateway to Sudan.

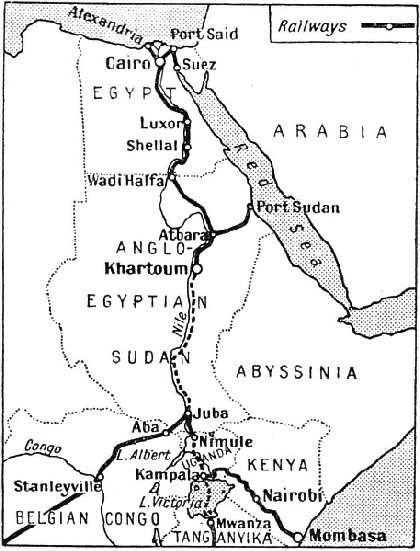

A COLOURFUL AND ROMANTIC JOURNEY can be made as shown on the map. On some stretches of the route changes from trains have to be made either to motor or river-

The journey south of Khartoum takes the traveller through a district called the “Gezira”. The “Gezira” is an extensive and well-

Situated at a distance of 237 miles from Khartoum is Kosti, the river port for Juba and South Sudan. From here the journey to Juba must be undertaken by river steamer.

This river trip brings the traveller nearer the equator, and owing to certain areas being infected with sleeping sickness, European and American travellers, unless they are in possession of a special permit from the Sudan Medical Service, have to travel to their destination by authorized routes. Juba is the headquarters of a province, Mongalla, and is the terminus of the Sudan Railways’ steamer service. The next stage in the journey to Mombasa is by the railway-

The first Uganda Railway was opened for service in 1901, and ran from Mombasa to Kisumu on Lake Victoria. In 1910 another line was built from Jinja on Lake Victoria to Namasagali, which connected up the Lakes of Victoria and Kioga. The two separate sections of railway were linked up in 1928, so that it is now possible to travel direct from Kamasagali to Mombasa.

Namasagali, the starting-

Steaming out of Namasagali the train climbs out of the Victoria Basin and crosses the border between Uganda and Kenya at Tororo. Beyond Tororo the line runs comparatively smoothly across the Uasin-

The Uasin-

Track through the Forest

At this point the train rapidly descends and passes through patches of primeval forests, remnants of the jungle through which the engineers had to hack their way when building this stretch, which is little less than a mountain railway. During the 43-

On this stretch of the route the train passes the station of Equator. This station is situated exactly on the equator line.

Part of this country, through which the train now travels, formerly belonged to the Masai tribe, at one time one of the most warlike of the African tribes. When it was first proposed to build the Kenya and Uganda Railway, an eminent statesman, who criticized the scheme, declared: “For every mile of rail laid through the country of the Masai, you will sacrifice the life of a white man.” But the railway builders went steadily forward, and the grim prophecy failed to materialize, for scarcely any opposition was offered to the railhead’s advance. The Masai merely regarded the steam-

Fifty miles or so beyond Timboroa comes Nakuru Junction, where the railway lines divides, one line continuing on to Nairobi and Mombasa, the other, the original pioneer line, turning westwards and proceeding to Kisumu in the Kavirondo Gulf, Lake Victoria.

Just above Nakuru there are incomparable views of its nearby lake, with the surrounding hills reflected in its placid surface.

After Nakuru the next feature of interest in the Great Rift Valley is Lake Naivasha, which the railway line skirts. The lake nestles in a semi-

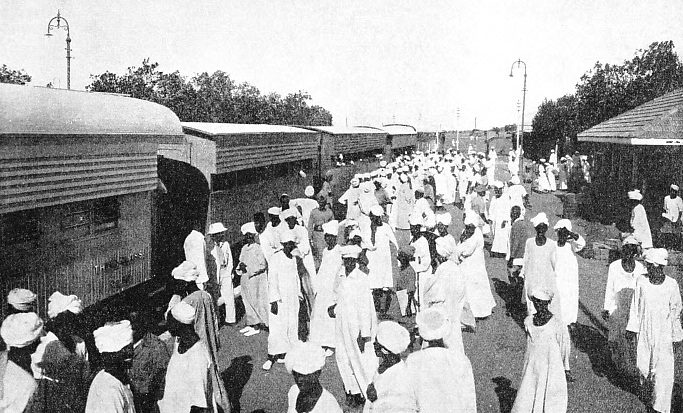

A TYPICAL SCENE on the platform in a station of tropical Africa. The clear-

South of this picturesque lake the railway passes a hot spring region where steam jets and sulphur-

A few miles from Naivasha comes Kijabe Station, situated on the lower part of the slope which leads up to the southern escarpment bounding the Great Rift Valley. After a long climb the train reaches the escarpment station at the top, and has crossed the 128 miles across the valley.

When the railway was being constructed, this difference of 450 ft between Kijabe Station and the summit of the climb from the valley caused a delay in the progress of construction. Eventually a method was discovered whereby the line could be taken down the cliff side with a reasonable gradient. Before this was possible many plans had to be drafted and re-

The solution of the difficulty was to take the line down the escarpment on an artificial sloping shelf hewn from the rock. The track had to wind and twist in an astonishing fashion so that this easy gradient could be obtained, and so that it would not be necessary to use a rack-

Africa’s Giant Engines

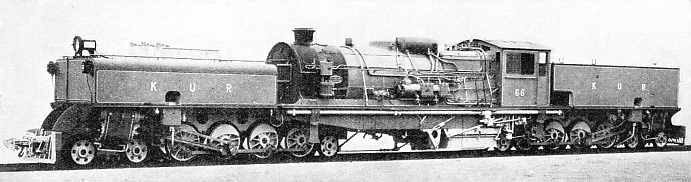

This engineering feat, assisted by suitable engines, now enables trains on the Kenya and Uganda Railway to negotiate frequent gradients of 1 in 50. One of the most common types of locomotive used is the large Garratt-

The latest introduced on the railway, weighing 134 tons, has a boiler pressure of 35,520 lb, carries 5,250 gallons of water and 6 tons of coal. The driving wheels are 3 ft 7-

Not far from Kijabe is Nairobi, the most important station on the main line, and the capital of Kenya. The town lies 5,452 ft above sea-

This is emphasized almost as soon as the train leaves Nairobi. In spite of the fact that the train passes through miles of rich farm land over the plains of Kapiti and Athi, the country teems with roaming herds of antelope, zebra, waterbuck and lions. Lions sometimes hold up a train by lying in the sun across the rails and refusing to move until the locomotive’s shrill whistle frightens them off.

From these plains there is a descent of 1,200 ft through a 30-

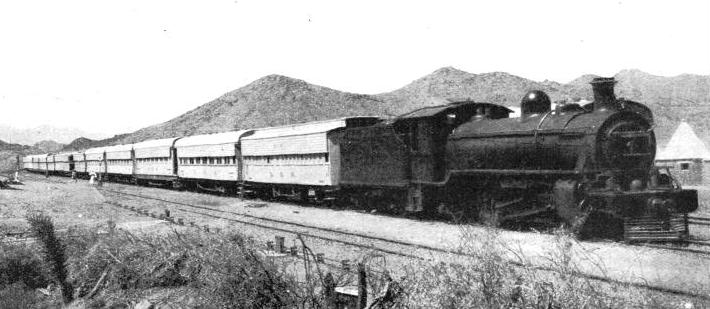

DESOLATE COUNTRY of the nature seen above is traversed by the Sudan Railway expresses. In some districts penetrated by the railway the total annual fall of rain is negligible -

After this rapid descent, which is another striking reminder of the difficulties which the pioneers encountered and defeated, the line crosses through the Emali plains. These plains are in the shape of a mighty grassland amphitheatre surrounded by hills of every shape and size, and the train passes from shelf to shelf of the uplands that lie behind the East African coast-

This reserve forms a splendid natural zoo, and, as the train passes by, wild animals can be seen in their natural state. These plains form an intermediate country between Nairobi and the coastal belt.

In this region, 130 miles from Mombasa, a bridge had to be built during the construction of the railway. Although the river had cut a channel between two lofty banks, the bridge was not a spectacular one. It was to consist of four spans, each of 60 ft, carried on three substantial stone piers. Since there was a complete absence of the facilities generally available for such work -

But, besides technical difficulties, there was another reason for delay. A large camp had settled on the east side of the river, and the building of the bridge was proceeding quite peacefully when a number of lions appeared in the night. The man-

Water for Life

Descending continually from the plains towards the coastal belt, the Namasagali -

The last stretch of line before the traveller reaches his destination lies through a pleasant and luxurious fruit belt extending some fourteen miles from the coast. Tropical fruits grow here in rich profusion, while tall palms and great mango trees cast varying shadows as they are stirred by breezes from the sea.

To gain Mombasa, on its island, the railway has to cross the Macupa Bridge, which connects the mainland by road as well as by rail.

The island is nearly encircled by the two arms of the mainland, the new harbour of Kilindini and the old harbour of Mombasa lying respectively west and east. Kilindini Harbour is the most sheltered port on the east coast of Africa and can berth a large number of ocean liners. The Kenya and Uganda Railway main line runs right along the side of the harbour, and the passengers on the train can make a swift change over from a trans-

Mombasa, the terminus after the long journey from Cairo in Egypt or Wadi Halfa in the Sudan, is a colourful town. Picturesque narrow bazaars of the old Arab town, with some of the native buildings adapted to present-

During recent years the Kenya and Uganda Railway has made steady progress, and the total track open to traffic at the end of December, 1933, was estimated at 1,625 miles. In that same year the railway’s earnings amounted to £2,088,162, as compared with £1,838,661 in the previous year. These figures are striking evidence of the progress of British railway enterprise in East Africa.

The traffic upon this line has exceeded the most optimistic anticipations.

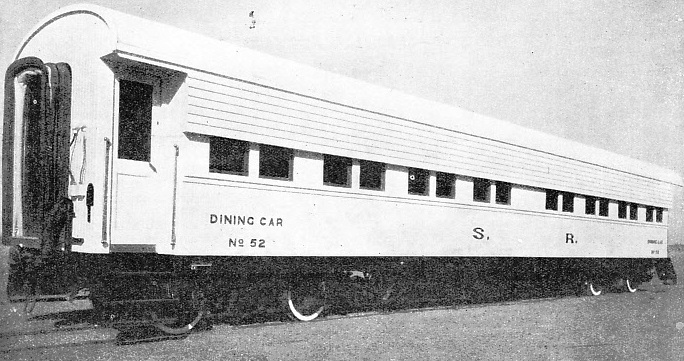

FOR PROTECTION AGAINST THE TROPICAL SUN and the pitiless glare of the desert, the dining-

The story behind the last part of the journey from Lake Victoria is worth telling. The original line, which extended from Mombasa to the terminus at the head of the Kavirondo Gulf, was built so that troops could be sent to assist in the suppression of the slave trade. The early railway lines in this territory were accordingly constructed primarily for military purposes. This was followed, after the beginning of the line, by the requirements of British development in Uganda, to hasten the completion of the connecting line of rail and water transport between Lake Victoria and the coast. The first real service given by the railway was in 1897 -

The caravan consisted of reinforcements dispatched to assist in the quelling of a rebellion in Uganda. The relief arrived in time to save the small white colony from massacre.

The length of the line between Mombasa Island and Kisumu -

The next extension of the railway was made imperative by continual development in other parts of Kenya and Uganda. The extension began with the building in Uganda of the Busoga Railway, a connecting link between Lakes Victoria and Kioga.

Other extensions began in Kenya, notably the Thika line, since taken on to Nanyuki, at the foot of the western slopes of Mount Kenya, some 140 miles from Nairobi. The Magadi Soda Company also built a ninety-

When the War came in 1914 all rail development, apart from one single strategic line, stopped. A new era in the East African railway world started, however, in 1923, and an increase in the number of miles in operation has never ceased since that date. In 1915 there were only 777 miles in this territory; to-

One of the most important recent enterprises was the Uasin-

The railways operating in this part of the world are comfortable and well-

On the corridor coaches used for any long distance, journey there are filters from which boiled water may be obtained. The journeys through Africa are as romantic as any in the world. On the trip from Wadi Halfa to Mombasa the traveller can see Roman fortresses, ancient temples of lost races, the beauty of the Nile and the desert, myriads of wild beasts and miles of the strangest-

The work of the pioneers, and the sacrifice of human life involved in the building of the railway in tropical Africa, have not been in vain. The Wadi Halfa-

THE LATEST TYPE of articulated engine as used on the Kenya and Uganda Railway. The locomotive’s total weight in working order is 134·2 tons, and its driving wheels are 3 ft 7-

To-

The most outstanding of the difficulties is the gauge problem. Most of the railways, for instance, in the Union of South Africa and in the countries of Equatorial Africa possess a 3 ft 6-

It is, of course, impossible to forecast exactly what direction railway development will take in Africa, but if during the next twenty years the numerous railways extend inland -

ON THE BUSY QUAY at Port Sudan, the railway runs alongside the ships, and many exports of Sudan are loaded into the waiting holds. The low buildings to the right are warehouses, while to the left alongside the quay is the side of a liner.

You can read more on “Across Africa by Rail”, “Pioneering in Nyasaland” and

“The Uganda Railway” on this website.