© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The Norfolk & Western Railroad

Collieries in the Pocahontas Field contribute 62 per cent of the Norfolk & Western’s coal-

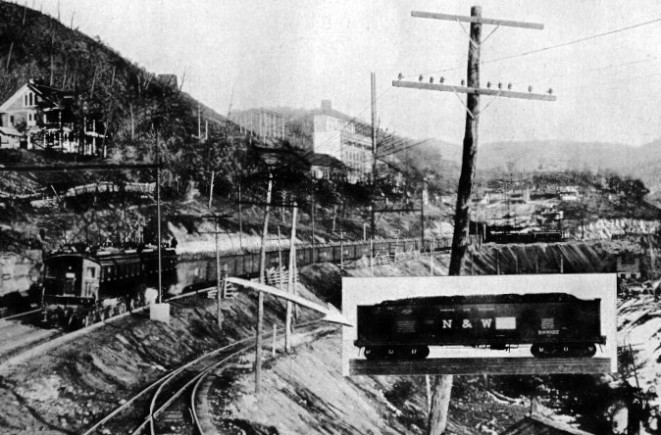

GIGANTIC COAL TRAIN ON THE NORFOLK AND WESTERN RAILROAD. The train is made up of forty 100-

THERE are many railways in different parts of the world which are essentially dependent upon the bulk movement of minerals — coals, copper and iron ore — for their revenue; the passenger and general freight business is relatively insignificant. Such a system is the Norfolk and Western Railroad with its 2,000 miles, which intersect the rich coal-

This network of steel, in common with many others, is handicapped by one weak link, about 30 miles in length, where the configuration of the country offers some features adverse to economical working — heavy grades and curvature. The men who plotted the road, upon penetrating the coal-

In pegging the location the pathfinders were influenced by the traffic conditions which ruled at the time. But the provision of railway facilities stimulated mining and coking within a confined area, virtually occupying all the land not acquired for the railway right of way. In the course of 10 miles through the most difficult section there are 54 main-

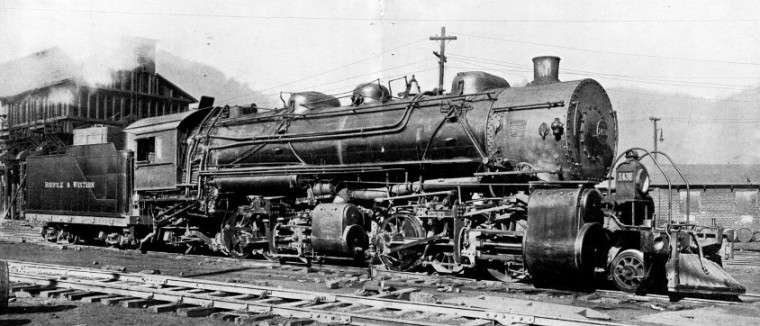

POWERFUL TYPE OF MALLET (2-

This congested traffic centre is known as the Vivian-

The grades are not the only harassing factor. Throughout this distance the line describes a meandering course, because it parallels, in turn, Elkhorn Creek and the Bluestone river — the only way out of the mountain-

The difficulties presented by the steep grades and sharp curvature are crowned by the tunnel leading to the summit-

For about twenty years the influence of the tunnel upon the railway’s fortunes was not materially observed. Up to that time train-

Before the latter was brought into service the operating department had perforce to realize the severe brake which the Elkhorn Tunnel exercised upon traffic. The locomotives attached to the heavy train and confronted with the long pull up the hill with its ruling grade of 1 in 50, were compelled to go all out, and as the hard pull against the collar continued through the tunnel the last-

This intolerable situation led to the introduction of a forced draft system of tunnel ventilation. The bank of smoke, steam and gases was driven ahead of the train by the ventilating fans, but this expedient did not completely overcome the difficulty. The tunnel was extremely wet, through the condensation of the steam, so that the locomotives became subject to severe slipping, and sometimes were stalled.

The railway made another advance in its locomotive power by the adoption of the “Mallet” compound. The first of these was brought into service in 1910. In practice the heaviest types of “Consolidation” were placed at the head of the train and the “Mallet” at the rear, the pusher being dropped at Bluefield. Ten of these units were acquired and proved so successful that larger and more powerful engines of this class were added to the fleet.

The success of the “Mallet” led to another modification of the operating system. The “Consolidations” were withdrawn from the service upon this section, and the “Mallets” left to handle the traffic up the grade to Bluefield and beyond. This revision became necessary owing to the persistent increase in the quantity of coal to be moved to the coast, and the introduction of larger cars to clear it from the collieries. In 1906, when the first of the heavier “Consolidation” fleet were brought into operation, the company had 11,756 vehicles of 50-

The “Mallets” were monsters of the 2-

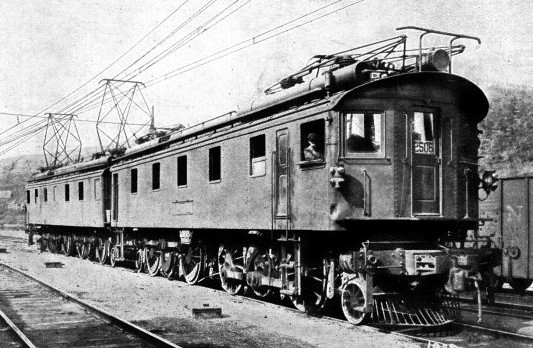

BALDWIN-

This development exercised the inevitable repercussive effect upon motive power. Larger and more powerful locomotives had to be acquired. Those of the new class — 80 of which were built —measure 101 feet 10 inches overall, weigh, light, 523,000 lb., and have a tractive effort of 104,000 lb.

These massive powerful units, twenty-

The drivers had to advance very slowly to avoid fouling the bank of smoke and gases belched from their engines, which was slowly driven ahead of them by the ventilating fans. Indeed, they often had to pull up to avoid the obstacle. Then, in restarting, further troubles became manifest. The drenched rails precipitated violent slipping and, if the leading locomotive happened to grip and get away before its consort at the rear, the effort exerted proved too much for the couplings; the train broke in two, and contributed to further delay and difficulty in maintaining the service. Twenty minutes was the time allowance for travelling through the shaft, but, frequently the negotiation of the 3,100 feet through the ridge took from thirty to forty minutes.

Topping the summit, with its following downward run of about 2½ miles, the locomotives were able to obtain a swing up the succeeding 5-

It will be seen that the use of the third locomotive was confined to assisting the train from Eckman as far as the west portal to the Elkhorn Tunnel, a run of about 11 miles. If the conditions were favourable its one crew could complete three round trips a day, each averaging 3¾ hours.

The return journey from the coast was with a dead load, when the train averaged from 75 to 100 empty vehicles, hauled by a single locomotive as far as Bluefield. Here a second engine was attached to the head of the train; double-

Although the coal traffic is the most important phase of the business conducted by the Norfolk and Western Railroad — it approximates 24,000,000 tons a year — the ten or twelve heavy coal trains have to be moved in accordance with a schedule such as will permit the running of four through passenger, eight local passenger, and eight mixed freight trains. It is the movement of the heavy tonnage mineral trains in the congested zone without delay to the other services, which imposes such a severe tax upon the operating department. Due provision has to be made for the unexpected when handling trains of such length and weight.

The coal traffic attained such proportions that the question arose as to how far the retarding influences of the Elkhorn Tunnel might be mitigated if not wholly eliminated. The obvious solution was the discovery of a new route for the line, or the driving of a second tunnel through the ridge so that up-

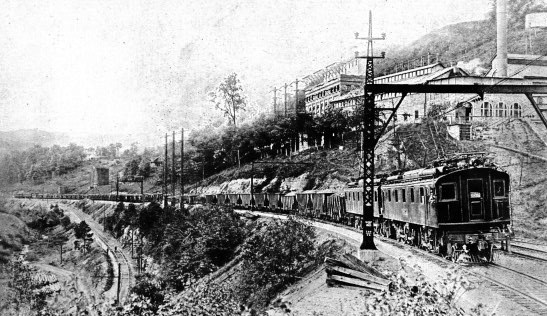

A TWO-

In 1910, the limitations of steam operation reached, the question of electrifying the tunnel and its difficult approaches surged to the top, and the Norfolk and Western Railroad decided to convert to electricity the 30 miles between Vivian and Bluefield, including the tunnel.

A power-

The electric locomotive fleet comprises twelve Baldwin-

maintain the service. It is extremely unlikely that the two units of an engine will develop a serious fault at the same time.

The introduction of electric locomotives for working the heavy coal tonnage has wrought a wonderful transformation. In normal service the nine electrics are performing more work than was previously forthcoming from twenty-

The benefits accruing from electrification were brought home very convincingly before the installation was completed. During the month of June, 1914, the last year of straight steam working, 272 trains, averaging 2,987 tons, were moved over the Elkhorn grade, each by three “Mallets”; the duty demanded 22 locomotives in constant service, these engines completing 21 miles in ten hours, or averaging one round trip of 42 miles every twenty-

During the corresponding month of the following year, by which time part of the electric locomotive equipment had been delivered, a mixed service, i.e. combined steam and electric working, was being operated. Four electrics and ten “Mallets” moved 397 trains, averaging 3,054 tons each, over the grade, the electrics handling 75 per cent, of the tonnage and working 63 per cent, of the mileage during the period in question. The electrics made two round trips, or 84 miles, in n hours 35 minutes — twice the mileage of the “Mallets” in less than half the time.

During the month single electric locomotives handled 45 of these trains, a pusher being used to lend a hand over the steepest banks; while on the return journey the single engine hauled a load of 100 empties. The electrics, however, revealed their superiority in another direction; there was no need for them to pass to the engine sheds upon the completion of the day’s work. It was by no means unusual for them to stay out on the road for fifteen days continuously, being subjected only to a superficial inspection upon the changing of their crews; further, this delay did not exceed in the aggregate 2½ out of the twenty-

A COAL TRAIN OF FORTY-

This experience proved conclusively that six electric locomotives could easily do the work which had previously demanded twenty “Mallets”, and led to the increase of the train loads. Even the heaviest trains, excelling in tonnage anything attempted under steam haulage, do not require more than two locomotives. Upon reaching the foot of the bank the second electric backs on to the rear, giving the help required up the bank and through the tunnel. The summit negotiated, the pusher drops clear ; the train continues its journey with the one engine to the Flat Top yard, where further vehicles are added to bring the total load up to 4,750 or 5,000 tons. The journey is resumed until the foot of the three miles’ pull at 1 in 83 is reached, when a waiting electric trundles along to bear against the tail of the train and thus assists it into Bluefield, where it is turned over to the road “Mallet” for its journey to the coast.

The round trip, Bluefield to Vivian and back, is made in the average time of seven hours, and two such trips constitute an average day’s work for the one train crew. The flexibility of the electric, its power and speed, bestow another advantage — immediate modification of the service according to fluctuations in the conditions. Each electric assigned to pusher duty makes five trips a day up the grade and through the tunnel, and also provides assistance in the distribution of the returning empties among the yards. These units are also available for the assistance of the through passenger and fast freight trains, swinging out of the siding to bear against the rear of the passing train and thus helping it over the bank ahead.

One of the most remarkable results of the conversion to electric operation is the elimination, in the traffic sense, of the “bottleneck” summit tunnel. Whereas the steam-

So punctual is the running of the electrics that the officials do not hesitate to allow the electrically-

The men handling these trains, and recruited from the crews formerly in charge of the ponderous “Mallets”, do not hesitate to express their preference for the electric. They emphasize the easier riding and marked freedom from jolting. There is no exposure to weather; the cab is more comfortable, with complete protection against the cold in winter and absence of exhausting heat in summer. There are no delays on the road to take on coal or to pick up water; there is always a clear look-

As a matter of fact, driving these huge machines is so monotonous as to render it difficult for the man at the handle to keep awake. The one speed, 14 miles per hour, is maintained uphill and downhill. This uniformity of speed is due, in the main, to the regenerative braking system. The only permissible variation in the scheduled speed of 14 miles an hour is on the last bank running into Bluefield, where speed, even with the 4,000-

One immediate result of the conversion was the reduction of the operating expenses from 65.9 per cent, to 56.8 per cent, during the initial six months, notwithstanding an increase of 16 per cent, in maintenance charges. During the year 1914, when steam ruled, 132,618 loaded vehicles were moved with 93,625 steam-

One aspect of the situation is not without interest. The cost of the electric locomotives, including development expenses and charges incurred to remedy certain mechanical defects after delivery, averaged £20,000 or £240,000 for the fleet of twelve. The “Mallet” steam locomotives, with a tractive effort of 73,000 lb., and scaling 425,000 lb. complete with tender, but empty, cost 4¼d. per lb., or approximately, £7,500 — a little more than one-

As a result of soaring prices of material due to the enormous demand occasioned by the Great War, these figures were appreciably increased, the respective costs in 1921 being £60,000 for the electric and £20,000 for the “Mallet”.

A STRIKING EXAMPLE OF ELECTRIC HAULAGE ON THE NORFOLK & WESTERN RAILROAD. A train of 37 loaded 100-

You can read more on “Articulated Locomotives”, “Giant American Locomotives”, “North American Railroads” and “The Union Pacific Railway” on this website.

You can read more on “Mammoths of American Railroads” in Wonders of World Engineering