© Railway Wonders of the World 2024 | Contents | Site Map | Contact Us | Cookie Policy

Steam v. Electricity

The inception and development of the electric locomotive

A THRILLING EXPERIMENT: A NECK-

AT the present moment [written in 1912] the most absorbing problem in railway operating circles is whether the steam locomotive, which has accomplished so much during the past century, shall be superseded by electricity. During the past few years the question has been debated very vigorously, and already many remarkable developments have been accomplished, while others of a more daring character are in course of consummation or are under contemplation.

From the activity which is being manifested at the moment, the average individual might be disposed to think that the electric railway is a new idea, or rather is a twentieth century movement. This is far from being the case. The propulsion of vehicles by electric energy aroused attention shortly after George Stephenson had demonstrated the possibilities of the steam locomotive at Rainhill.

The fact that electricity was destined to play an important part in railway operation was shown conclusively for the first time by a British experimenter, Robert Davidson, of Aberdeen. In 1842 he built an electric car which ran on the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway, now incorporated with the North British Railway, which, laden with passengers, attained a speed of 4 miles an hour. Davidson’s idea, however, was premature. The electrical energy was drawn from batteries, and at that time such a system was hopeless. Moreover, commercial interests were riveted too closely at the time upon the steam locomotive. Still, Davidson was the pioneer; he was the first to demonstrate what could be done with electricity as a means of moving wheeled vehicles along the steel highway.

THE 3-

The subject of electric traction occupied the minds of the savants in both hemispheres for many years, but little was accomplished until Werner von Siemens, the famous German electrical scientist, devoted his energies towards the solution of the problem. In 1870 a decided step forward had been made by Zenobe Gramme’s invention of the ring armature; thence the dynamo underwent rapid development.

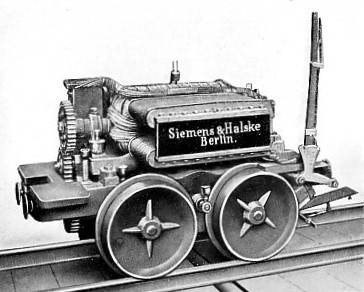

Siemens’ electric locomotive was unpretentious. It comprised a 3-

THE SIEMENS ELECTRIC RAILWAY at the Berlin Exhibition, 1879.

This Siemens electric railway, although regarded as little else than a “side show”, virtually inaugurated the electric railway era. For the first time it was recognised that a possible rival to the steam locomotive had arrived. Thomas Edison was attracted to the problem, and he laid down a short length of experimental track near his laboratory at Menlo Park. His engine likewise was very primitive, comprising a flat truck on which the dynamo was installed.

In co-

Before Edison had completed his second experimental railway, electric traction had entered upon the commercial phase in Great Britain. On August 26th, 1880, a company was incorporated to construct a railway 6 miles long from Portrush, in County Antrim, to Bushmills, to be worked by electric power. Simultaneously Mr. Magnus Volk received permission to lay a narrow gauge railway along the beach at Brighton. This was opened for traffic on August 2nd, 1883, shortly after the Irish line, and it is historically interesting as being the first English electric railway.

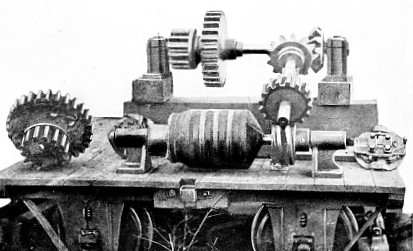

THE GEAR OF EDISON'S first electric locomotive.

Once the possibilities of electric traction became appreciated — in which development the Old World led the way— curiously enough, the idea of adapting it to street tramways became the first and foremost consideration. Its application to the railway languished considerably for many years, but the dawn of the twentieth century revived the idea, especially in those countries deficient in fuel resources, but possessed of incalculable sources of energy in the form of waterfalls, such as Sweden, Switzerland, and Italy. Millions of horse-

Therefore it was only natural that such countries should attempt to elaborate schemes for the harnessing of this waterpower, and its transmission over vast distances to points where it could be used. But the conditions of railway service differed very materially from those incidental to street tramways. There were many peculiar problems inherent to the former which did not arise in the latter development. Accordingly, it became necessary to embark upon elaborate and costly experiments for the purpose of determining the means of meeting the situation most effectively and economically. Unless a decided advance could be made upon steam locomotive practice from every point of view, then electrical operation would be difficult to bring about. The railway managing element is notoriously conservative, and argues with no other weapon beyond pounds, shillings, and pence.

The most striking tests carried out in this connection were those made by the New York Central Railroad in conjunction with the General Electric Company of Schenectady. This railway was the only one at that time which ran direct into New York City, but the terminal had to be approached through a bottle-

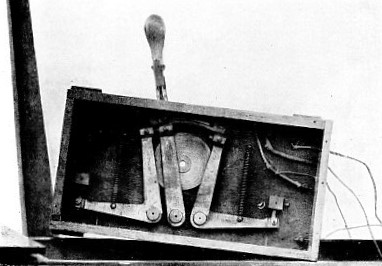

THE CONTROLLER of Edison's first electric locomotive.

This initial step, however, was one of considerable magnitude. It comprised the electrification of the main line for a distance of 34 miles from the terminus, together with 24 miles on another — the Haarlem — division. The two sections, however, represented two totally different services, the first-

The locomotive used for the test was to be capable of pulling a load of 875 tons — the maximum weight of an express train — at speeds ranging up to 65 miles per hour. The conditions were somewhat exacting. Seeing that the weights of the express trains vary, and that some fifty locomotives of one type were to be supplied for the service, it was decided to adopt the multiple unit system of control. This arrangement gave extreme flexibility. By this means two locomotives can be coupled together and operated from the leading engine as a single unit. Such a “double-

The locomotive was of the 2-

Hour after hour, for day after day, through three months this locomotive was run up and down the experimental track, hauling loads of varying weights. Minute records were kept of every run, so as to afford complete information upon any possible issue which might be raised by the railway authorities.

The Opponents Compared

The supreme test was made on April 29th, 1905, when it was decided to obtain comparative data of electric and steam haulage. The electric locomotive was pitted against one of the latest and most powerful steam locomotives engaged in the express service, the two being run side by side. The steam monster was of the Pacific type, with cylinders 22 inches in diameter by 26 inches stroke, having 3,757 square feet of heating surface, measuring 67 feet 7¾ inches over all, and weighing, complete with tender, 171 tons, of which 23½ tons were concentrated on each driving axle.

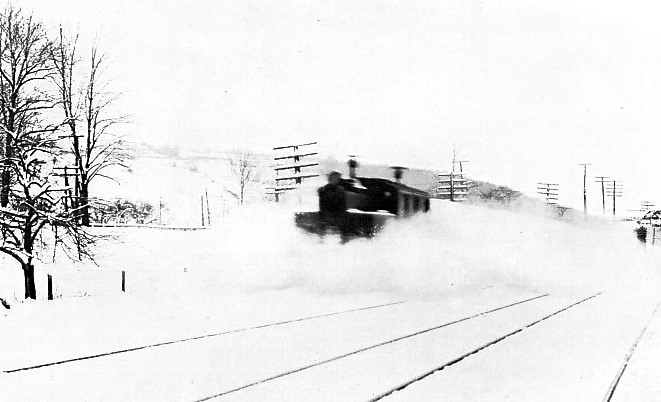

THE TRIUMPH OF THE ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE: DRIVING THROUGH A SNOWDRIFT. In the early days of electric operation it was stated that snow would prove an insuperable obstacle. To disprove this contention the New York Central Railroad drove a train through heavy drifts which had piled up on the track after a blizzard.

The electric locomotive measured 36 feet 11¼ inches over all, and weighed 100½ tons, with 17¾ tons concentrated on each of the four driving axles. Thus the electric locomotive was 30 feet 8½ inches shorter and weighed 70¾ tons less than its steam rival, while the difference in axle weight was 5¾ tons in its favour.

The first run was made with a trainload of eight coaches. The total load of the steam train, including the engine, was 513 tons. Owing to the lesser weight of the electric locomotive, the latter’s train was loaded up with 70¾ tons so as to bring its weight approximately to that of its rival.

The two were lined up side by side, the electric on its own road, and the steam train on the west-

Another run was made under similar conditions, and the results were virtually the same. The electric train, though slower in acceleration, owing to the drop in the voltage, caught the steam train and drew clear before the current was shut off. On this test higher speeds were attained by both trains, the steam locomotive reaching 53·6 miles, while the electric train topped 60 miles, per hour.

For the third run the trains were reduced to six coaches, bringing the weight of the steam train down to 427 tons, and that of the electric train to 407½ tons. Here again the steam train got away more quickly, but in this case the voltage dropped as low as 330 volts. The result was that during the first half-

Another run with these trains was completed, only in this instance, in order to secure still closer relative results, and to bring the electric train more analogous with the conditions which would prevail in the electrified zone around New York, the start was made from the second milepost. By this means a higher voltage was obtained, owing to the start being made nearer the sub-

These tests were followed with intense interest by the officials for whose benefit they were conducted. Two heavy trains drawn by powerful monsters racing neck-

Upon the conclusion of the foregoing tests two runs were made by the electric locomotive in order to ascertain its speed powers. In the first sprint only one coach was attached, with which a maximum speed of 79 miles per hour was registered. In the next effort the locomotive was run light, and with the current shut off on curves. Despite the latter handicap the locomotive recorded 80·2 miles per hour. This run was decidedly impressive, and had it not been for the restriction on the curves, it is believed that 90 miles an hour would have been put up. As it was, the above performance was excelled two days later, when the engine in a speed burst attained a velocity of 85 miles per hour, with speed reduced to 78 miles per hour when rounding the sharpest curve.

These tests emphasised the overwhelming superiority of the electric locomotive. Whereas the steam train starting from rest required 203 seconds to accelerate to a speed of 50 miles an hour, its electric rival notched the same speed in 127 seconds. Then, again, the paying load behind the electric locomotive was 76 tons greater than that behind the steam locomotive, all other things being equal.

The officials of the New York Central Railroad were convinced of the possibilities of this form of traction upon the electrified sections of their system, and they entertained no apprehensions concerning the wisdom of their policy.

Subsequent experience has fulfilled their anticipations completely; their enterprise reaped its due reward. To-

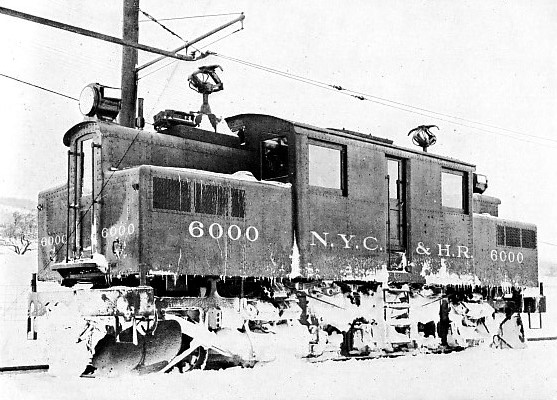

THE ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE AFTER ITS CONTEST WITH THE SNOWDRIFTS.

You can read more on “Brighton’s Electric Railway”, “Electric Power on the Grand Scale” and “Electric Traction” on this website.