© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

An Experimental “Pacific” Locomotive

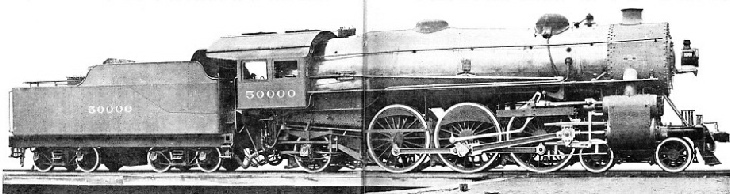

In Building Their 50,000th Engine the American Locomotive Company Evolved an Interesting Design of the “Pacific” Type

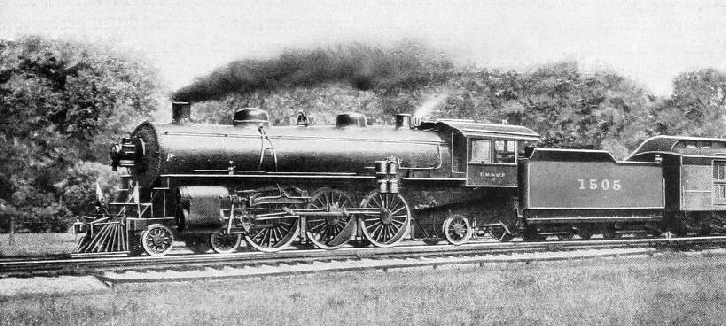

A CHARACTERISTIC “PACIFIC” (4-

THE builder of the locomotive, in meeting the requirements of a railway, is compelled to submit to the rigid specifications laid down by his client. The result is that the engine is not always so efficient as it might be, as the personal question, as represented by the engineer or manager of the railway, enters into the issue. To prove this point, and just to ascertain what could be done if the firm’s engineers were given a free hand, the American Locomotive Company, which is an amalgamation of a number of locomotive builders, decided, on the occasion of the construction of its 50,000th engine, to carry out the work upon its own initiative. The engine was admitted to be an experimental engine, designed and constructed at the company’s own expense. Accordingly, being untrammelled by any particular specifications, or the necessity to conform to the existing standards of any railway company, the builders were free to embody in this particular locomotive their ideas concerning the best locomotive engineering practice.

In the execution of this interesting experiment the company did not attempt to evolve anything freakish or unusual. They simply took an existing type of engine and improved it in accordance with their accumulated experience, which is con-

The Pacific class is a logical development of the Atlantic 4-

Under these circumstances, therefore, the American Locomotive Company, by its selection, had a good opportunity to excel, especially in view of the acknowledged need of greater sustaining capacity to meet the requirements of modern passenger train working.

The builders set out to provide the maximum power per pound of weight, and they succeeded in a remarkable manner, seeing that under tests in actual service the engine has developed 2,216 horse-

AN EXPERIMENTAL “PACIFIC” (4-

The end which the builders set out to attain has been achieved by the fullest application of the most approved developments in locomotive design and materials. The latest knowledge of general proportions, the most recent developments in materials, improvements in the design of details the best use of accepted fuel-

In order to accomplish the primary purpose of the design, the largest boiler capacity within the predetermined wheel loads was the essential feature. Every pound of weight that was not necessary to secure strength or durability in the component parts was eliminated. The weight thus saved was utilised for the provision of a larger boiler, and the increase of the capacity of this boiler by the provision of fuel-

The boiler has a diameter of 76⅜ inches, and steam is used at a pressure of 185 pounds per square inch. The fire-

The driving wheel base is 14 feet, that of the engine 35 feet 7 inches, and of the engine and tender 68 feet 2½ inches. The weight of the engine is distributed as follows: Leading wheels, 24¾ tons; driving wheels, 86¼ tons; and 23½ tons upon the trailing wheels. The total weight of the engine, therefore, works out at 134½ (American) tons. The tender, of the 8-

The total heating surface of the locomotive is 4,048 square feet, the superheating surface 897 square feet, and the grate area 59·75 square feet. This is far in excess of any other superheated Pacific locomotive of equal weight. In superheating surface alone the area exceeds that provided in any other American passenger engine built up to the time of its appearance.

The cylinders, with a diameter of 27 inches by 28 inches stroke, are of vanadium cast steel, and weigh 2,600 pounds less than cast steel cylinders bushed with cast-

Several distinct innovations in regard to American locomotive practice have been introduced. The steam pipes connecting with the cylinders are placed outside, and although a radical departure it has been received favourably. The screw reverse gear, which has become adopted almost universally on British and European engines, was provided for the first time. This appropriation of an Old World idea was not regarded favourably at first in many quarters, inasmuch as the American locomotive engineer is wedded to the reverse lever, despite the fact that its handling is becoming increasingly difficult in large engines, and that it represents loss of economy and efficiency. But the driver, the man who has to handle the machine, and who has been brought into touch with the innovation upon this engine, has expressed his preference for the screw reverse, once he has become used to it, very un-

Many other refinements to secure the builders’ ends were incorporated, and have tended to show that, although the United States engineers have made great strides in the development of the locomotive, the skill of the Old World is by no means exhausted in this particular field, and that true advance only can be made by the mutual exchange of ideas.

That the builders of No. 50,000 carried out their experiment upon the right lines is borne out by the fact that many of the improvements over long-

So far as American locomotive development is concerned this is the first instance on record where a private firm has built a locomotive upon its own initiative and at its own expense for the purpose of advancing locomotive design. The engine has been tested freely, and has given complete satisfaction to all who have handled and watched its performances. The engine is acknowledged to steam easier, and to impose less physical exertion upon the fireman in the maintenance of the steam pressure, than other Pacific engines of conventional design up to the appearance of No. 50,000.

[From Part 13 of Railway Wonders of the World by Frederick A. Talbot, 1913]

You can read more on “The Coming of the Ten-