A wonderful machine for laying railways along great distances

TRACK TOPICS - 6

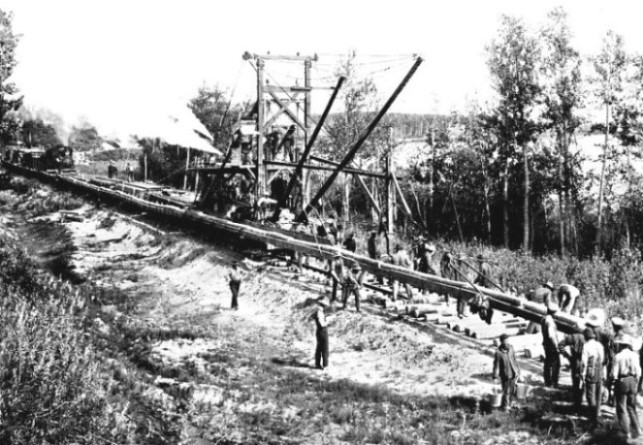

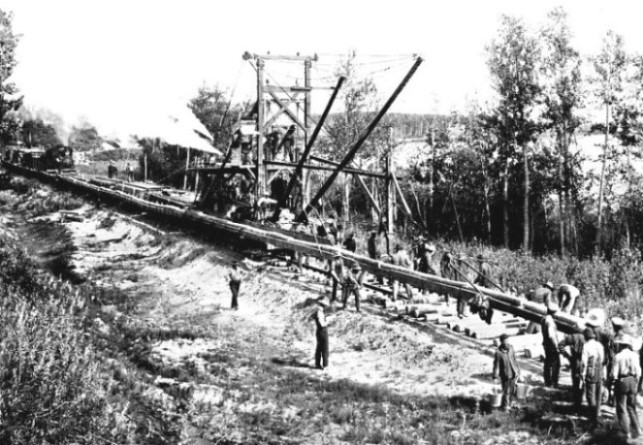

THE HURLEY TRACK-LAYER AT WORK. This machine lays and spaces the sleepers on the ground and sets the rails.

ONE of the most interesting developments, from the mechanical point of view, has been the perfection of methods for laying the metals. So far as Great Britain is concerned there is no need to depart from the practice of laying sleepers and rails which has obtained since railways came into being. Mechanical systems never would pay here, because the day of big railway undertakings seems to have drawn to a close. The mechanical track-layer, to prove its value, demands a clear run of several score miles; then its force is demonstrated somewhat powerfully.

In order to obtain the most telling expressions of its utility one must visit Canada and the United States, where railway expansion upon a huge scale is in progress. Hand labour never could cope with this situation; metals and sleepers are weighty to handle. So of necessity the mechanical system was evolved.

The track-layer is mis-titled somewhat, according to Old World interpretations of railway building. It does not lay the track lock, stock, and barrel complete for service — it simply dumps the sleepers on the ground and places the rails upon them. The two are then temporarily gauged up and secured together. It is merely a skeleton track, sufficient for the movement of constructional trains and material to the front. The track has to be completed by hand in the usual manner before it is fitted for ordinary service. Still, by laying the metals in this manner the saving in human muscle, physical exertion, and labour in the first instance is very appreciable, because throwing about heavy baulks of timber measuring 8 feet in length, by 8 inches wide and 6 inches deep, and 33-feet lengths of steel weighing maybe 90 lb. and 100 lb. per yard, is hard, slow work. At the same time it enables the glittering ribbon of steel to advance more rapidly through the country than is possible under manual methods; the railhead is kept in closer touch with actual work upon the grade.

THE ADVANCE OF THE TRACK-LAYER, showing the grade ahead on the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway.

Although the track-layer may differ in many details of construction, the fundamental design and principles of operation are common, except in one instance, which will be described later. It is a cumbrous, lumbering piece of machinery carried on a flat car. At its forward end is a gantry or gallows-like structure, from the base of which project two booms, one on each side, whence the rails are handled. The deck of the car carries the steam plant for the supply of power to the machinery, while on an upper platform are stationed two men who carry out the delicate task of setting the rails in position. In a crow’s nest, immediately beside these men, and commanding a complete uninterrupted view of the whole operations in front, sits the man in charge of the track-laying gang.

Immediately behind the track-layer come the trucks piled up with the steel rails, and an adequate supply of fish-plates. Then follows the engine, and lastly the deck cars stacked high with the sleepers. The locomotive thus is placed in the centre of the equipment. Extending along one side of the train, from end to end, is a big wooden trough, through which the sleepers are conveyed from the trucks to the grade beyond. This trough projects some 40 feet or more beyond the track layer. Thus the sleepers are shot on the ground more than a full rail length ahead. The bottom of this trough is fitted with rollers armed with spikes, which, in revolving, grip the under side of the sleeper and propel it forward. The baulks are hurled through the trough in a continuous stream, the supply to the forward gang being governed entirely by the rate of the feed from the trucks into the conveyor.

The operation is very simple. The constructional engineer has left the grade carried to formation level; its surface is clean, level, and clear. Down the centre of this pathway runs a row of pegs corresponding to the location stakes of the surveyor. As these pegs coincide with the centre line between the rails, the foreman casts off his distance on one side and sets his gauge line.

LAYING THE RAILS, showing the trough for conveying sleepers at the side. With this machine 126 miles were laid in 26 days on the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway.

The track-layer lumbers up to the end of the completed track under the pushing effort of the locomotive, and then work commences. The track-laying gang is distributed over the train and the grade in front. The conveyor rollers rattle and clank; the men on the first sleeper truck behind pitch the baulks into the trough as fast as they can. With an ear-splitting din the timbers are hurried forward, and are disgorged upon the grade ahead. As rapidly as they fall out of the trough they are prised, pulled, pushed, and tugged into position, spaced the requisite distance apart, while care is seen that one end toes the gauge line at the side.

Meanwhile the men on the trucks laden with the rails temporarily attach a pair of fish-plates to one end of a 33-feet length of steel, which is caught up and whisked to the front. It is lowered steadily, the free end drops between the two fish-plates on the last rail laid, bolts are slipped through to connect up, the gauge is struck, and with a few deft swings of the heavy sledges the gangers drive a spike here and there to clinch the metal to the sleepers below. In the first instance the work is perfunctorily carried out, everything being trued up hastily.

Directly a rail on each side has been laid the machine crawls forward. The extent of this intermittent advance varies according to whether the joints in the rails are in line or broken. In the first instance progress will be the length of a rail; in the second case only about half that distance. The noise is deafening. The screech of steam mingles with the rumbling and growling of the sleepers as they come bumping along the wooden conveyor trough. There is the ring of steel as the rails are swung out and lowered, and the clash of metal as the heavy sledges are swung to drive home the spikes and bolts. Above all may be heard the raucous shouts and orders of the man in the crow’s nest, and the babble of the 120 odd men, probably of half a dozen nationalities, shouting with the force of megaphones to make themselves heard.

Under favourable conditions the metals can be laid at an average rate of two miles per day. When the going has been particularly advantageous, and a full gang of expert men has been available, the railway has crept forward between four and five miles between sunrise and sunset. There is a friendly rivalry among the crews, and if a chance presents itself, they let themselves go with infinite zest in the effort to create a day’s record. But the track so laid is extremely crude — a skeleton line in the fullest sense of the word, and little better than that laid down by the constructional armies for the movement of their ballast wagons and material. When the track-layer has passed and the strip of white level grade has received its steel embellishment, the line looks as if it had been twisted and buckled by a seismic disturbance, or had writhed under extreme expansion set up by an abnormally hot summer’s day.

Hard on the heels of the track-layer come the aligning and levelling gangs. They straighten the kinks in the ribbon of steel, correct all the sags by lifting and packing ballast under the sleepers, and complete the trueing and bolting up, as well as the spiking to every sleeper. Over this skeleton track, trains may move forward at slow speed — say up to six or eight miles an hour. As the rails are laid on the sub-grade, and ballasting is not carried out until later, very little effort is required to throw the track out of gauge. On one journey on the engine of a construction train shortly after the metals had been laid, three times in as many miles the engine dropped between the metals owing to the spreading of the rails. But the construction train expects such interludes, and, in anticipation, carries a goodly supply of tackle aboard in the form of powerful jacks, whereby the engine is lifted back again without very much trouble or serious delay. Then the train is backed a few feet, and

the men on board fix up the road by bringing the rails into gauge so that the train may pass.

The foregoing type of track-layer has been that in general use for many years, and has given general satisfaction. From time to time the details are improved, for the purpose of facilitating the avowed task of the machine. One man who had completed such an improvement came to an unfortunate end. He was on the track-layer, giving instructions, when he slipped. Before he was able to recover himself he was on his back in the sleeper conveyor, was caught by the spikes on the rollers, and was ground to death by the ever-moving stream of timbers before he could be extricated.

Recently a distinct improvement has been effected upon the foregoing type of machine. The latter does not lay the track, it merely delivers the material for manual power to set in position. Still, when it is remembered that, upon a modern railway of standard gauge, the aggregate of metal and wood which has to be handled represents a matter of 350 tons per mile, it will be acknowledged that it constitutes a very helpful auxiliary.

The latest machine, known as the Hurley Track-layer, better justifies its name, inasmuch as it automatically lays the sleepers and rails in position on the ground. Manual effort is reduced to the minimum. The whole working principle of the Hurley apparatus differs from that of the ordinary appliance. Instead of moving forward intermittently a matter of 16 feet or so at a time, it travels constantly — very slowly, it is true — as the drive is transmitted to the wheels through reducing gear, the speed being designed so as to ensure continuity of track-laying and progress simultaneously. A locomotive for pushing purposes is not required — the plant is self-contained, and a distinct working unit. The travelling speed varies from 12 to 40 feet per minute, far slower than a locomotive could move, and at this speed it can haul a train, ranging up to thirty laden cars, according to the grade.

The mechanical car carries a pair of reversible stationary engines which suffice to actuate the machinery and to drive the train. From this car projects a huge truss, which overhangs the grade, whereby the sleepers and rails are delivered to the ground. Immediately behind the engine car is the fuel and water supply truck. This can be detached from the track-layer and hauled back to the loading point to be replenished at the end of the day’s work. Then follow the trucks loaded with the sleepers, which are stacked transversely. The train is completed with the cars laden with rails. Instead of a conveyor trough, two rollers are laid on each side, and at the respective ends, of each car.

The modus operandi is very simple. Work commences at the first car of rails behind the track-layer, the rails being stacked in the form of a pyramid on the flat truck. This latter is fitted with a portable frame, or gantry, the legs of which drop into pockets in the frame of the vehicle. This frame carries an overhead friction hoist. The rails are lifted one by one from the stack and lowered on to the rollers, where they are connected together by slipping a couple of bolts through the connecting fish-plates. The result is that the rails move forward in a continuous length to the track-layer, travelling over the rollers at the side. When the first truck has been exhausted of rails, the gantry is lifted out of its pockets and transferred to the succeeding vehicle, and so on until the whole of the rails have been sent forward.

THE “LIFTING” GANG TRUE-ING, LIFTING AND LEVELLING RAILS and completing spiking to sleepers on the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway.

As the rails move along the rollers they pass over the trucks laden with the sleepers, but underneath the two sides of the stack, and in such a way as to be clear of the latter. On each of these trucks are piled from 375 to 500 baulks, according to the length of the vehicle. As the rails travel forward, men stationed on the wagons roll the sleepers on to them, so that the rails really become a conveyor. Other members of the crew, standing on side planks, space the sleepers upon the moving track the same intervals apart as they will occupy when laid on the ground. Thus one sees a length of inverted track moving constantly towards the front of the train.

When the moving rails with their sleepers reach the engine car, the two become separated, the rails passing between friction rollers, which supply the forward moving effort to the rails, while the sleepers are sent upwards, still the allotted distance apart, over the top of the machine, along the upper side of the truss, and are delivered on to the ground by means of a conveyor. As the track-layer is moving forward constantly, and owing to the truss overhanging the grade ahead, the sleepers are tumbled exactly into their requisite position, and the correct distance apart upon the ground. All that has to be done is to see that they toe the gauge line, men armed with tongs effecting this adjustment without undue effort. As the truss gives a clearance of 8 feet clear above the roadbed, there is ample space for the men to work beneath.

The rails, after parting company with their sleepers, and being drawn through the friction rollers, are detached. The fish-plate bolt is withdrawn from one end, while the other is loosened, so that the two fish-plates are left on the rear end of each rail. This task completed, the rail is drawn forward by means of speed rollers, and passes along the lower edge of the truss to a point about 20 feet ahead of the front of the car. Here it is grabbed by specially fashioned tongs, and lowered until the rear end drags along the rail previously laid. It is held suspended until it has come within some 12 inches of the end of the rail on the ground. A man then swings the suspended rail forward until the attached fish-plates drop over the end of the previous rail, the pressing tendency of the swinging length of metal being sufficient to keep the two ends together until a clamp, which holds both fish-plates and rails together, is applied, when the tongs are released. A bolt is slipped in to join the new to the previous rail, the clamp is released, the forward end of the rail is lowered upon the sleepers, while bolting-up and spiking here and there are accomplished during the interval the track-layer is moving forward 20 feet. Thus the machine moves on to the new length of metal without a pause.

The machine section of the train is a weighty mass, turning the scale at some 65 tons, but this weight is distributed over a wheel-base of some 50 feet. As the Hurley track-layer completes the whole operation without the assistance of a locomotive, a saving from £5 to £8 per day under this heading alone is effected, while as a smaller crew is sufficient to handle the complete equipment than in the case of the ordinary type of track-layer, the machine is both money- and labour-saving.

Some remarkable achievements have been placed on record with this machine. A force of 42 men can lay 2 miles of track a day, while a small squad of 18 hands can complete 1¼ miles in the same time. With an expert full crew, 1,800 feet of metals have been laid in an hour. Weather conditions do not affect the working speed, and even swampy ground can be crossed in safety, and without inflicting the slightest damage upon the road-bed, owing to the long wheel-base and distribution of weight. In Wisconsin 3,000 feet of track were laid in a couple of hours, notwithstanding the fact that during the greater part of this time a blinding snowstorm was raging.

The apparatus is just as effective upon curves as upon stretches of tangent track. The overhanging truss is able to swing to the curvature, owing to the construction of its front end, and the sleepers are deposited to the centre line upon the ground under all conditions. From the money-saving point of view its value is forcibly emphasised, judging from results achieved in building the Kansas City, Mexico and Orient Railway, where the engineer-in-chief estimates that the machine has saved him over £40 per mile, as compared with other methods of track-laying.

Subsequent to the passing of the tracklayer the road has to be overhauled from time to time —ballasted, lifted — so as to bring it into the pink of condition for fast and heavy traffic. If the actual cost of construction is compared with the manual system practised in Great Britain and Europe generally, it is doubtful whether it shows any advantage, but it certainly offers a means of getting the metals down more quickly, so as to provide an improved and accelerated means of transporting material, and men for grading, to the front.

LAYING THE METALS AT THE RATE OF FIVE MILES A DAY. The track-layer at work on the Chicago, Milwaukee and Puget Sound Railway.

You can read more on “The Permanent Way” , “The Railways Daily Work” and “The Track’s Heavy Artillery” on this website.