© Railway Wonders of the World 2024 | Contents | Site Map | Contact Us | Cookie Policy

Flashlight Signalling

A system in practice in Sweden whereby special signals are unmistakably identified by engine drivers

THE MAGIC OF MODERN SIGNALS -

A THREE-

ALTHOUGH the British railway signalling system is conceded to be as near perfection as is humanly possible, and certainly is superior to that found in any other part of the world, whether considered from the points of efficiency, simplicity, or reliability, it is admitted that modern railway conditions demand improvements to safeguard high speed travelling at night.

In the British night-

But when one recalls the vast array of signals which are displayed to guard busy junctions, one will realise that the selection of his particular signal light is by no means an easy task for the driver. The issue becomes complicated when running round a curve, since as the junction is approached the signal lights may change their relative positions. For instance, a signal which the driver picks out as his own may be seen to the extreme right of the others when entering the curve, but when the latter has been rounded it may have shifted its position to the extreme left.

Again, one must remember that on the British railways every mile of line is guarded. The driver of a London and North-

Again, one must remember that on the British railways every mile of line is guarded. The driver of a London and North-

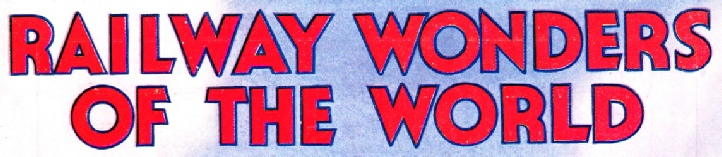

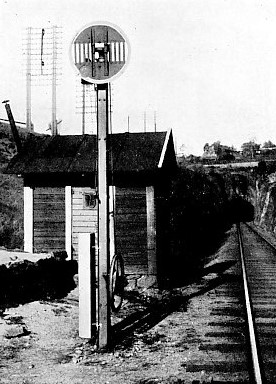

A DISTANT SIGNAL ON THE DANISH STATE RAILWAY, FITTED WITH THE AGA FLASHING LIGHT.

“Watching for signals” constitutes the most trying part of the driver's duty, and, what is more to the point, he has got to interpret each signal as it looms up. Anyone who has travelled on the footplate of an express at night, and has experienced varying descriptions of weather, will admit that the situation of the driver is by no means enviable. Even the finest, longest and quickest sight is tested to a supreme degree in picking up and in interpreting correctly a signal during a blinding hail or rain storm, while the layers of mist, hanging at varying heights, are apt to obscure a signal so completely that the train is upon it before it is seen.

From the express driver’s point of view his labours are enhanced very appreciably by the lack of distinction between the distant an i home signals. Both show the same light characteristic, although they convey totally different instructions. Of the two, the distant is the most important, as it indicates the probable position of the home signal and, if adverse, warns the driver to ease up, although by the time the home signal comes into view the line may be shown as clear.

Although many people regard a driver in the light of a highly developed sensitive governor, as it were, of the machine under his hands, he is human after all, and, consequently, is liable to err. The most expert driver will admit that at times he loses his bearings, and, although he is quick in picking up his whereabouts, much can happen in the short period of distraction. Accidents have probably occurred purely because the driver has passed his distant signal unconsciously, or has mistaken the home for the distant signal, while the instances where disaster has been averted narrowly because the driver has discovered his mistake in the nick of time are legion. Fortunately, the majority of drivers do not depend upon the eye alone, but are able to divine their situation with tolerable accuracy from the noise of the train, especially if they are thoroughly familiar with the road. Indeed, the sensitiveness of the ear in the expert driver is as remarkable as the quickness of his sight.

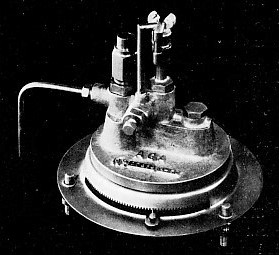

NEW TYPE ACCUMULATOR-

After all is said and done, however, it is obvious, seeing that so much depends upon the detection and interpretation of the distant signal, that it should be given a distinctive characteristic. On some systems an effort to this end is made by giving the light a violet tint, but the objection to this procedure is that this colour possesses a very indifferent penetrating capacity. It cannot be detected from such a distance as red or green.

How can the distant signal be given a distinctive characteristic, and one which will catch the driver’s eye as easily, if not more readily than that in vogue? This question arose upon one of the private railways of Sweden, and the authorities embarked upon a series of experiments in this direction. A variety of suggestions were advanced and investigated minutely, but were abandoned as impracticable for various technical reasons. Then one of the engineers, conversant with the fact

that flashing lights are used at sea, and are highly appreciated by mariners owing to the facility with which they can be picked up and interpreted, suggested that trials should be made therewith.

It was not an experiment in the usually accepted sense of the word, because the marine flashlight had been reduced to a scientifically correct and practically commercial basis. Dr. Gustaf Dalen, the eminent Swedish scientist, whose researches upon light phenomena are so famous, had solved the question very completely for marine purposes. Accordingly, the railway requested the organisation exploiting Dr. Dalen’s inventions, the Gas Accumulator Company, Limited, of Stockholm, to apply the idea to railways, if at all feasible. Seeing that this was the first occasion on which the company had been asked to adapt flashlight signalling to railways, and realising that the conditions between land and sea travelling were so different, an interesting series of tests were undertaken with a view to evolving the system of flashing best suited to railway working. Finally, it was found that, from the optical point of view, little modification was required: the question became resolved into the adaptation of the idea to railway operation, but as this was a mechanical issue no difficulties were anticipated, and, in fact, were not encountered.

The Swedish railway signalling engineers who had suggested the development were strengthened in their opinion that a flashing system of signalling would be more effective from the fact that the human eye is more sensitive to intermittent interruptions of a ray of light than to a steady gleam. In other words, a light which is caused to flash at regular and at comparatively short intervals will be detected more easily and from a greater distance than the steadily burning light. The value of the flashing light as a means of arresting attention is demonstrated every night in the busy thoroughfares of our big cities, where flashing advertisements have displaced steadily illuminated signs, merely because they catch the eye. Even if a flashing sign is surrounded by a number of constantly illuminated advertisements, no matter how brilliant the latter may be, the former with its alternating dark and light periods will strike the eye, while the others may be passed unnoticed. This is because the eye notices the flashing sign involuntarily.

When the first flashlight signal was applied to a railway, similar results were observed. The driver of a train detected the flashing signal, and realised its significance long before he recognised the stationary lights. Also he found it easier to individualise it from a bewildering array of warnings, and, what was more to the point, he was able to notice the light without particularly looking for it. Moreover, knowing that the flashlight mounted upon the distant signal guarded his train, he sought for that only. If he failed to find it, he became uneasy and at once slowed down his train until the home signal was picked up, and his confidence was restored.

A driver who is protected by flashlight signals suffers less physical and nervous racking. He has one character of light only to pick up, and he looks for it, ignoring all other lights which may be in the vicinity. His signal may be placed upon a gantry where perhaps fifty green and red steady lights are gleaming, but instantly he singles out the flashing light. As the mariner, when feeling his way along a coast, is able to select his flashing light from the host of other land and ship lights, so is the railway driver able to find out his particular beacon. Even in misty and blusterous weather, when a steady light can be picked up only with extreme difficulty, the flashing light is detected with extreme ease and from a longer distance. The possibility of confusion is eliminated entirely, while there is neither hesitancy nor doubt.

The preliminary tests on the private railways of Sweden having established the unquestioned value of the flashing light, the development underwent extensive application. It received a decided stimulus by the accident which happened at Kibs Station on the Bergslagens Railway, owing to a driver misinterpreting a signal. The flashing light was installed to prevent a repetition of the disaster, and since this installation has been in service the drivers running through this junction have confessed that their labours have been eased very appreciably, and that they can approach the junction, even at highest speeds, with less doubt and hesitancy than was the case under the previous fixed light method.

In Sweden the flashing system is displacing the older method very rapidly, both upon the private and Government lines. The drivers of the expresses have urged the necessity of a distinctive class of signal for their particular work, and have stated emphatically that, in the protection of a high-

It is obvious that the flashlight system cannot be applied to all existing signals. It must be used in conjunction with the ordinary type of fixed light. If all signals were converted to flashing the plight of the driver would be worse than it is now. There would be as little, or even less, distinction between various signals; in fact, the driver would be harassed more than ever.

The advocates of the system maintain that it should be used for special work, such as the guarding of the fastest expresses. It might be applied to distant signals, so as to distinguish them completely from the home signals; or, on the other hand, the steady light might be retained for the distant signal, and the flashlight restricted to the home and through station signals. In the latter event the driver, even if he over-

If used in this connection, running through the busiest and largest junctions would be facilitated, even if the main lines branched off into half-

If used in this connection, running through the busiest and largest junctions would be facilitated, even if the main lines branched off into half-

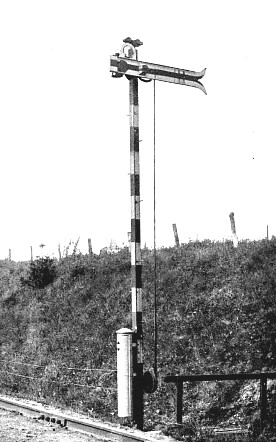

PUTTING IN A FILLED ACCUMULATOR (old type of box).

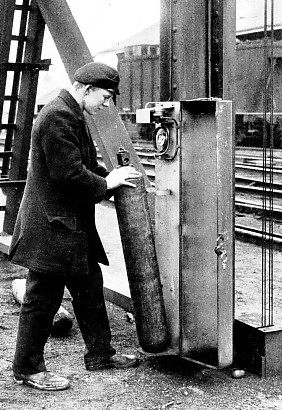

The “Aga” system, as that invented by Dr. Dalen is called, is absolutely automatic in its action, and is used in conjunction with acetylene gas. It is cheap, while a single charge is adequate for two months’ working without attention. The light burns both night and day, so that the signal is always lighted — a distinctive advantage in countries susceptible to fog visitations. The essential feature is the flasher, whereby the distinctive light characteristic is obtained. It comprises a small reservoir, into which the gas flows from the accumulator, fitted with a burner. When this reservoir is charged a valve is opened by the gas pressure, and the charge of gas escapes to the burner, where it is ignited by the pilot flame. This flasher has been in use in connection with lighthouses, lightships, and buoys for many years past, so that its practicability, efficiency, and reliability are assured. The apparatus can be adapted to produce as many flashes per second as may be required. The complete installation for every signal is of a very simple character, and in the majority of cases can be fitted to the existing type of lamp. The acetylene gas in the dissolved form is stored in a small portable accumulator, resembling the cylinder in which oxygen and other gases are compressed, placed in a small box at the base of the signal post, and connected to the lamp through a supply pipe. Being in the dissolved form the acetylene is perfectly safe to handle, while there is no danger of explosion whatever. The size of the accumulator, its capacity, and, consequently, its working period, may be varied according to the situation of the signal, but in the majority of cases an accumulator sufficient for two months’ service is used.

Owing to the simple design of the flasher, the few integral parts, and their strong construction, the danger of breakdown is eliminated, while the possibility of the signal failing to act is inconceivable. Once the accumulator is coupled up to the flasher, and the pilot flame is lighted, the apparatus continues its work regularly until the supply of acetylene is exhausted. The reliability of the invention may be realised when it is stated that some of the first flashers installed upon the Swedish railways have produced over 100,000,000 flashes and have never once failed or shown the slightest sign of irregularity in working. Bearing in mind the rigorous character of the Swedish climate, with its extreme fluctuations in temperature, and the severity of the winter, blizzards and rainstorms, it will be admitted that the apparatus has been submitted to as severe a test as could be conceived. Completely satisfactory working under these conditions should be sufficient to prove that the apparatus is adaptable to any railway on the globe.

THE AGA SEMAPHORE LAMP WITH FLASHER MOUNTED.

At first sight it might be thought, as the light flashes both day and night, that it may be somewhat costly to run. This is a fallacious impression. The average cost comes out at about 100,000 flashes, or 70 hours, for one penny. This is far cheaper than any other system in vogue, and its economy is augmented by the fact that the item of wages is reduced, because the lamp only requires attention once in two months or so to renew the accumulator charge. All that is neccssary is to disconnect and withdraw the empty reservoir, and to introduce and connect up the charged vessel, examine the burner, and light the pilot flame. The whole operation can be completed in a few minutes, and the signal can then be left safely for another two months. Under the present system a man is required to light and extinguish the lamps at dusk and dawn respectively, and this duty represents an appreciable item in the wages bill. Upon foreign and colonial railways, where the labour problem is somewhat acute, the flashing system, apart from its other advantages, offers a complete solution of a very difficult question.

When the system was first taken up in Sweden, the question of the duration of the light and dark periods and the number of flashes per minute demanded solution, so as to secure the most perfect results from the driver’s point of view. An elaborate series of tests were carried out to this end, and a mass of interesting data was collected. When this detail was resolved the following points were established:— (1) That a comparatively short light period gives the most characteristic signal. (2) That the dark period should not exceed 0·9 or one second, because the driver is apt to lose his bearings, develop feelings of uneasiness, or be mistaken if the period of darkness is longer. (3) That the duration of the light period, within certain limits, is of secondary importance, a flash of 0·1 second duration scarcely being distinguishable from one twice the length. (4) That about 60 flashes per minute form a first-

THE AGA FLASHING APPARATUS FOR RAILWAY SIGNALS.

But the number of flashes per minute must depend to a great extent upon the local conditions and the character of the traffic to be protected by the signals. The driver must receive a sufficient number of impressions between the moment he first sights the light, and when he is at a point affording him ample space in which to pull up easily before reaching the signal. When a train is travelling at sixty miles an hour from three to five flashes are necessary to convince him on this point, and at sixty flashes a minute the train will have travelled from 264 to 440 feet during this period. If the flash is very short, experience has proved that a somewhat greater number of flashes are requisite to convey an unmistakable impression. In Sweden, where the flashlight has been applied to distant signals, the flash character is 0·1 second light followed by 0-

At the Liljeholmen station on the southern main line of the Swedish State Railways, where the Aga flashlight system has been introduced on the home signals, several different flash characters have been employed in order to determine whether the flashes of relatively long light periods are effectively distinguishable from the short flashes of the distant signals, and also to ascertain which of the four flash characters is the most suitable. The flash characters under test are respectively as follows:—

0·4 seconds light followed by 0·8 seconds dark, 50 flashes per minute

0·5 seconds light followed by 0·8 seconds dark, 46 flashes per minute

0·5 seconds light followed by 0·7 seconds dark, 50 flashes per minute

0·5 seconds light followed by 0·5 seconds dark, 60 flashes per minute

Since the system was introduced experimentally upon the private Swedish railways it has made great strides. The State railways have embraced the idea, being convinced of its value, and it will not be long before the whole of the lines are guarded in this manner. In Denmark, Russia, and Holland the invention is regarded favourably. While certain of these installations are purely of an experimental type, the results so far have been so satisfactory that little doubt is entertained that they will be adopted. So far as Great Britain is concerned, our railways are watching the development of the idea very closely, the fact that it might be adapted to certain phases of express main- eing manifested. In these latter cases a comprehensive signalling system throughout the two countries is in process of fulfilment, the railways spending huge sums to bring their roads into line with European practice. Seeing that the Aga flashlight system is absolutely automatic in its action, is very economical both to install and maintain, requires the minimum of attention, in addition to giving a very convincing and distinctive warning, it undoubtedly constitutes an ideal signalling system for new countries. Moreover, the complete success of the idea in its application to marine lighting is a powerful recommendation in its favour.

eing manifested. In these latter cases a comprehensive signalling system throughout the two countries is in process of fulfilment, the railways spending huge sums to bring their roads into line with European practice. Seeing that the Aga flashlight system is absolutely automatic in its action, is very economical both to install and maintain, requires the minimum of attention, in addition to giving a very convincing and distinctive warning, it undoubtedly constitutes an ideal signalling system for new countries. Moreover, the complete success of the idea in its application to marine lighting is a powerful recommendation in its favour.

A DISTANT SIGNAL ON A SWEDISH RAILWAY FITTED WITH THE AGA FLASHLIGHT.

You can read more on “Railway Signalling”, “Seen From the Train” and “Sweden’s Rail System” on this website.