© Railway Wonders of the World 2024 | Contents | Site Map | Contact Us | Cookie Policy

Railway Searchlights

A description of the powerful electric headlights which illumine the track half a mile ahead of the locomotive

THE PYLE-

THE public is notoriously exacting and querulous in matters pertaining to travel. It sees no reason why the same speeds should not be maintained under the blackness of the night as during the brilliancy of day, disregarding the huge strain that is thrown upon the senses of the driver. He is expected to pick up any possible obstacle on the metals a hundred yards ahead at midnight as readily as at midday. If the conditions under which the driver labours are revealed to the passenger, the latter retorts in his ignorance that the driver has his locomotive headlight to assist him to detect dangers ahead. When he is told that such a light is useless, and is rather intended for identification purposes by railway operators, such as signalmen and others, he is somewhat nonplussed.

So far as the United Kingdom is concerned, the glimmering oil light may be adequate. The lines are fenced in, are well patrolled, and are protected efficiently by block signalling devices, but in new countries, where settlement is sparse, the conditions are vastly different. Often the line is not fenced, or only in a perfunctory manner, so that an eye has to be kept open for big beasts of the bush, which are apt to turn the right of way into a promenade. A bridge may have collapsed; a tree may have been blown across the metals ; a boulder may have rolled down the mountain-

But the public must not be condemned to daylight travelling only. It has become accustomed to luxurious sleeping coaches, and has developed the tendency to move from point to point during the hours when business is suspended, and sleeps away the interval of inactivity. In order to meet these requirements attempts, therefore, were made to provide the driver with a more efficient means of illuminating the track ahead for a considerable distance, so that perfect safety might be attained when travelling at express speed during the night.

The electric light was an obvious handmaid to this end. Accordingly, efforts were made to adapt it to railway service. Experiments were undertaken in this country, but the lack of encouragement for such a contrivance was a deterrent to endeavour. Besides, so many difficulties of an exasperating nature loomed up and defied subjugation so completely that inventors became somewhat disheartened, and abandoned their labours. In the United States, however, where the demand for such a searchlight was more acute, inventive effort was not cast down so easily. One, if not the first, experimenter was Leonidas Woolley. He commenced his experiments at his home in Dayton, Ohio, and laboured long and hard at the perfection of a small, compact, and simple device. Before he had carried the idea sufficiently far to build a working model, he moved to Indianapolis, Indiana. Here he produced a small electric headlight machine in 1883, and success seemed assured. But there came a bitter disillusion. The device was rigged up on a locomotive, and burned promisingly while the engine was standing still. Directly it commenced to move, however, the light went out, and resolutely refused to burn while the locomotive was in motion. Woolley dismantled his apparatus, and, somewhat chagrined, took it back to his home for further development upon different lines.

His initial effort spurred another inventor to action. This was Charles J. Jenney, who, in 1885, produced an electric headlight which was placed on one of the engines of the Big Four Railroad, running between Indianapolis and Cincinnati. But Jenney experienced difficulties similar to those which had befallen Woolley, although the railway company in this instance, recognising the possible germ of a great idea, persevered with the innovation, and endeavoured to make it work. Still, their perseverance proved unavailing, and so, after making a few trips, the machine was taken off.

Woolley had by no means been idle, though it was not until 1887 that his next effort attracted attention. In that year a new equipment was brought out by the American Headlight Company, and was placed upon an engine of the Cleveland, Akron, and Columbus Railroad, and also on one of the Pan Handle Railroad, running between Indianapolis and Columbus, Ohio. While these machines were considered to be a marked improvement upon anything which had been attempted in regard to electric locomotive headlights up to this time, they proved far from reliable. The railways struggled with them for several weeks, and then reluctantly relinquished them; the manufacturing company discontinued experiments and went out of business.

In 1888, Robert B. F. Pierce, of Indianapolis, appeared upon the scene. He foresaw the future of such a headlight, and determined to bring it to a successful issue. He interested a few of his associates in the project, among whom was George B. Pyle, an electrical engineer. The patents of other inventors were acquired, and with this nucleus the National Electric Headlight Company was organised, with Pyle toiling strenuously to evolve success out of failures. Finally, he effected certain improvements, and a machine was submitted to the railways. It was fitted to an engine, and after a few galling failures and many adjustments, completed a journey from one terminal to another without a breakdown. This achievement was hailed with unfeigned delight, and the distinction of being the first company to produce a working electric headlight thus belongs to the above organisation. But the machine did not triumph completely. It proved quite a trouble-

In 1897, Mr. Royal C. Vilas took up the idea, and founded the Pyle-

The optimism of the inventors proved to be justified fully, and appreciation of the invention was forthcoming instantly. In the following year 472 of these headlights were installed upon the locomotives of the various railways throughout the United States and Canada. To-

The success of this invention, once its reliability was assured, has been phenomenal. This is due to the efficiency of the machine under all and varying conditions of railway working, simplicity of the details and construction, durability, and fool-

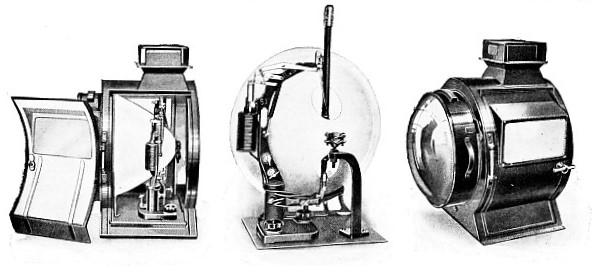

THE TURBINE DYNAMO of the Pyle-

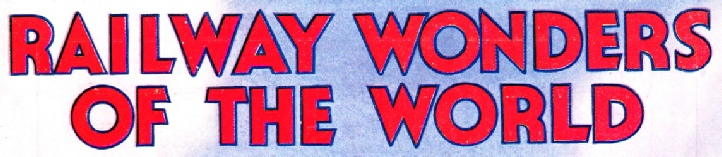

The Pyle headlight is a small, compact machine, comprising a turbine-

The dynamo is of simple construction, the armature being held on the turbine-

The governing arrangement, likewise, is of the simplest form, having but one wearing surface, the friction of which is taken up by a composition disc, so that no internal lubrication is required. The governor is set at 2,400 revolutions per minute, the normal velocity of the turbine, but the speed may be varied as desired by altering the tension of the spring through the movement of two nuts. The steam-

The steam is led to the veins on the rotor through a single nozzle, and attached to the nozzle-

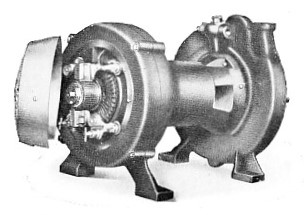

A HEADLIGHT with incandescent electric lamp for shunting locomotives.

For ordinary service an arc lamp is used, and the ordinary oil headlight can be adapted to electric operation. The American locomotive headlights are more formidable than those employed in these islands. Conversion from one to the other is simple, and may be effected easily and quickly. All that is necessary is to remove the oil reservoir and burner, together with all supports and guides from the parabolic reflector with which the oil light is fitted. A special support for the reflector is then inserted at the back, and adjustment is made until the front of the reflector is vertical. Then the lamp is inserted. The carbon holder is of simple, durable, and reliable design, and the adjustment is so easy that within a short time the driver is able to trim and adjust it in the dark. Inasmuch as it is possible, although remote, that the light might fail suddenly when out on the road through mishandling, carelessness, or some other fault, the delay need not be serious, since the driver can remove the electrical installation, from the headlight case, and reinsert the oil lamp, which is carried for such an emergency. The arc-

The horizontal shaft of light is thrown across the full width of the right-

The strides which the electric headlight has made during the past few years is remarkable. The Pyle headlight has been fitted to over 20,000 locomotives of 295 railways scattered between the two poles. One railway in the United States has no fewer than 1,500 in operation, while several systems have 800 or more in use. The public has come to appreciate the fact that travelling by night in a train, the locomotive of which follows a penetrating white beam, is as safe as by day. Legislation also has supported this development. The State of Wisconsin promulgated a law, which came into effect July 1st, 1912, compelling all railways within the jurisdiction of the State to equip their locomotives “with a headlight of sufficient candle-

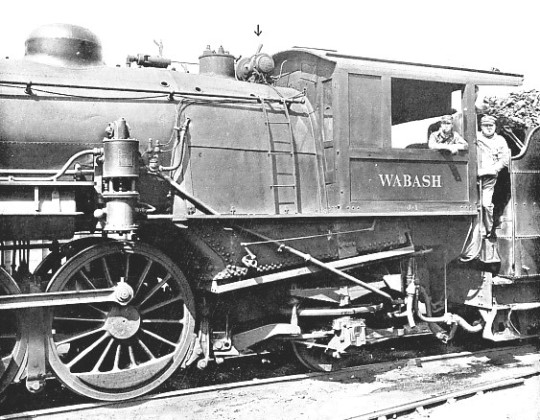

A LOCOMOTIVE FITTED WITH DYNAMO (MARKED BY ↓) FOR HEADLIGHT. The dynamo is turbine-

You can read more on “Development of the Locomotive Fire-