© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

Railways and the General Strike

How the General Strike of 1926 Affected Railway Services

THE origins of the General Strike are complex. Suffice it to say that what had started out as an internal dispute within the sorely troubled coal industry had gradually snowballed into a full-

THE origins of the General Strike are complex. Suffice it to say that what had started out as an internal dispute within the sorely troubled coal industry had gradually snowballed into a full-

An emblem of the National Union of Railwaymen.

According to the first issue of the British Worker, the Trades Union Congress newspaper issued during the General Strike of 1926, “the strike early laid its paralysing hand on the great railway station at Carlisle, where seven important lines converge, forming a railway hub second in importance to none in the country. Within a few hours the usually animated platforms were deserted and desolate. Passengers arriving early in the morning could get no farther by train, but some were able to proceed in hired motorcars to Glasgow or Edinburgh, paying as much as £25 a time.” The stoppage of rail transport was complete.

Government preparations had included arrangements for an emergency transport system organised by road commissioners and local haulage committees. The political and economic significance of maintaining communications had been grasped from the outset. The Trades Union Congress also took the point but simply assumed that a railway stoppage would paralyse the country. The role of motorised transport had been completely underestimated. In the event it was to prove the government’s most decisive weapon. Drivers were recruited by the thousand, largely from ex-

Initially, at least, the unions could congratulate themselves on a magnificent display of labour solidarity. On the London Midland & Scottish Railway, for instance, only 207 out of more than 15,000 engine-

In retrospect, the General Strike has attracted its fair share of myths. It was remarkably non-

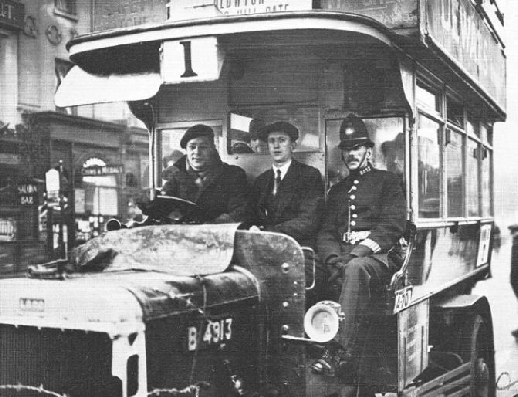

Volunteer drivers kept bus services operating during the General Strike.

But driving an engine calls for greater skill than driving a car. It was one thing to allow medical students to career around in buses to the delight of their friends and the terror of their luckless passengers, it was quite another to turn them loose on the railways. Reading complex signals or threading one’s way through a tangled mass of track and points called for a lifetime’s experience and expertise and to maintain a head of steam on a gradient was a matter of fine judgment, as many of the volunteers were to learn the hard way. Just as the short-

Some of the volunteers’ escapades seem to have been positively hair-

“He travelled from Warwick Avenue tube station to Baker Street. The first hitch was a stop in the tunnel, which put all the lights out. When the alarm caused by that had subsided, the train crawled along until Baker Street was reached. There, the American, who was standing on the platform of the car next to the locomotive, heard an agonised voice calling to the conductor: ‘I say, Bill, I can't start the darned thing. Give me the instructions.’ The conductor handed him a clip of leaflets; in a few minutes a buzzing sound from the locomotive began suddenly and as suddenly ended. Then the voice again: ‘Bill, I've touched the wrong handle and the brake’s gone fut. Send for the chief engineer. . .’”

Baker Street is also immortalised in the recollections of a young girl drama student who wrote the following account of her journey home to her mother:

“There, everybody carries your luggage for you and is awfully nice. It is perfectly mad to hear, instead of ‘Arrer ‘n’ Uxbridge’, a beautiful Oxford voice crying ‘Harrow and Uxbridge train’. Ticket collectors say thank you very much; one guard of a train due to depart, an immaculate youth in plus-

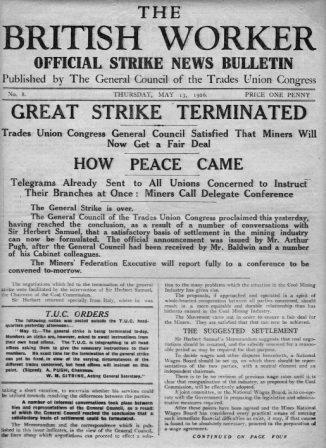

Issue of the British Worker announcing the end of the General Strike.

Maintenance, of course, was sadly neglected. It was unglamorous, attracted few volunteers and was poorly organised. As the strike lasted only nine days, however, the neglect never became a factor of major importance. If the experiences of one volunteer platelayer are anything to go by though, things might well have become serious had the stoppage lasted much longer. “We spent one day in a dreary fen between March and Ely”, he recollected, “shovelling granite chips between the metals. By the end of the day we were so blistered that there was no question of turning up again next day”. An undergraduate who later became headmaster of a well-

“Our work was done by gangs of four under a non-

landed astraddle of the live rail, we became more cautious. Current off, we proceeded, two down each tunnel, knocking in with a sledgehammer any of the wooden blocks which had fallen out or seemed likely to do so.

“This was easy enough -

There were many minor accidents on the railways during the General Strike, but only one serious one and that the result of the single known instance of deliberate sabotage. Stone-

On May 12, the return to work was ordered by the unions and the railways faced a special crisis of their own. The railway unions, whose support of the whole general strike undertaking had been considered vital, had in fact only decided to support it after much agonising hesitation. Union leaders realised that their men were in many cases more easily replaceable than the miners they were backing up and would, moreover, be obliged to bear in person the brunt of the public's displeasure. And the railway companies had made their attitude quite clear. The GWR, for instance, had warned its employees that their means of living and personal interests were involved and the LNER had issued a notice to the effect that striking railwaymen would be regarded as having acted in breach of contract. It was scarcely surprising, therefore, that the railway companies should have used the unions’ surrender to the government as an opportunity for settling old scores by victimising activists.

The companies’ attitude was, however, not without its ironic aspect, given the attitude of J. H. Thomas, leader of the National Union of Railwaymen. A dedicated social climber with the highest political ambitions, he had withdrawn the support of the railwaymen on a technicality when the miners had tried to force a showdown in 1921. In the last-

J. H. Thomas, leader of the National Union of Railwaymen.

Thomas continued to press for a resumption of negotiations throughout the nine days and was, indeed, largely responsible for the unions’ abject capitulation. All the more ironic, therefore, that it should be the railwaymen who faced the most ferocious anti-

(1) Those employees of the railway companies who have gone out on strike to be taken back to work as soon as traffic officers and work can be found for them. The principle to be followed in reinstating to be seniority in each grade at each station, depot or office.

(2) The trade unions admit that in calling a strike they committed a wrongful act against the companies, and agree that the companies do not by reinstatement surrender their legal rights to claim damages arising out of the strike from strikers and others responsible.

(3) The unions undertake (a) not again to instruct their members to strike without previous negotiation with the company; (b) to give no support of any kind to their members to take any unauthorised action; and (c) not to encourage supervisory employees in the special class to take part in any strike.

(4) The companies intimate that, arising out of the strike it might be necessary to remove certain persons to other positions, but no such persons’ salaries or wages will be reduced.

The last provision covered companies demoting signalmen to station porters and the unions had no choice but to accept. Among the many concessions they were obliged to make was the suspension of the “guaranteed week” which assured

their members of a basic wage. Even so, about 45,000 men, nearly a quarter of the membership of the National Union of Railwaymen, had not been re-

Analysing the failure of the General Strike in the Observer, J. L. Garvin, the famous columnist, asserted that the defeat of the Trades Union Congress had been inevitable from the outset, “Because its whole system of thought is stupid and out of date and years behind the progress of modern science and mechanism. Nearly twelve months ago, when the plan was threatened in earnest, we told Socialist Labour what would happen. We agreed with them that transport was the key, but we told them that in an age of motor traffic multiplying year by year on every road, they can never seize that key.”

A motor car manufacturer put it more simply in an interview with the Daily Mail, “motoring has once and for all knocked the possibility of a serious transport strike on the head. With half a million capable motor drivers in the country it is an anachronism.”

You can read more on “Coaches for Road or Rail”, “Railways and Buses” and “Railways and Publicity” on this website.