A journey across Canada from the footplate

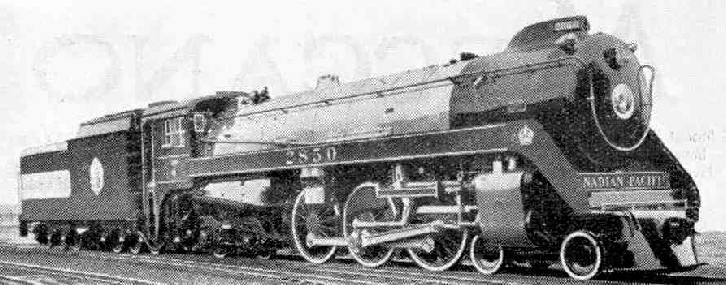

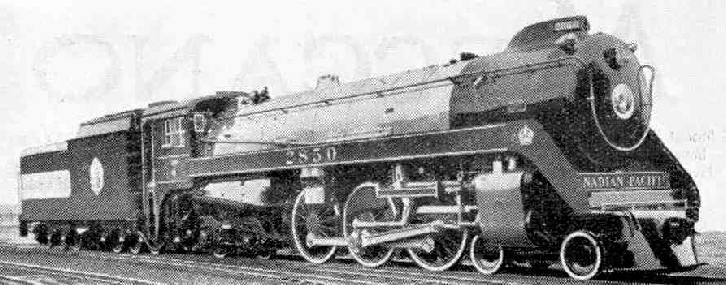

No. 2850, THE CANADIAN PACIFIC “HUDSON” class locomotive that hauled the Royal train across Canada in 1939.

IT IS a simple matter to cross Canada by train. You merely get into it at Halifax, on the Atlantic coast, and stay on it until you reach Vancouver, on the Pacific, 3,770 miles West, five days later—though you have to change cars at Montreal, and spend several hours there. This is when travelling by the Canadian National Railway route; the Canadian Pacific has another, from St. John. Countless people have taken this journey since the completion of the C.P.R half a century ago. I have crossed the continent in locomotive cabs! Nearly, that is. Truth compels me to admit that sleep was necessary sometimes, and that then I betook myself to a berth in the train. However, I can claim to have done 75 per cent of the transcontinental trip on the footplate. This article deals with one section of the journey, the 419 miles from Fort William to Winnipeg, especially interesting because the engine was the C.P.R. 4-6-4 “Hudson”, No. 2850, which hauled the Royal train right across Canada in 1939. The C.N.R. provided motive power for the return trip.

First, something about the route, and the chief places concerned. The twin cities of Fort William and Port Arthur lie on the shores of Lake Superior. Coming into Fort William from the east, the track has been twisting, turning and snaking for hundreds of miles through the rocky wilderness of New Ontario, and along the northern shore of Lake Superior. Fort William is a Divisional point, where the engines that have brought the train through from Toronto, 811 miles, come off. Leaving Fort William for the west, the train parts company with the lake, and plunges on for 294 miles to Kenora, by the Lake of the Woods, and thence across the Ontario boundary into Manitoba at Telford, where rock and trees begin to disappear, sinking into the level prairie that continues for over 900 miles to Calgary, at the foot of the Rockies. Winnipeg is 81 miles beyond the Manitoba border, and 419 miles from Fort William. There are many considerable gradients in this distance, and though the actual overall rise is only 149 ft, there is an interesting peak at Raith of 967 ft, 53 miles from Fort William, and farther on several other little pimples too. It is a double track route, much easier going east than west; how do you think that comes about? I will explain the puzzle later.

Now for the engine. This is of the 2800 H1d “Hudson” class, with a 4-6-4 wheel formation, and is a fine looking engine, as shown at the top of this page. When I made its acquaintance it bad lost its colourful Royal trappings, and it is now running in the smart standard C.P.R. Livery of chocolate and black, gold lined. The running board, lower cab-sides and tender-panels are of the former colour; the smoke-box, wheels, etc., black. The crown just over the cylinders is now carried by all the 2800 class engines, but the Royal Arms on the smoke-box door and tender have been removed. The 4-wheel trailing truck, which is fitted with a booster, is necessary because the weight of the fire-box is too great for a single axle; “Pacifics” have largely disappeared in America for this reason. The booster is a small 2-cylinder engine - about 8 in. by 12 in. - driving the second axle of the trailing truck through gearing, and is brought into action at starting to give an additional “boost”. It is cut out at or below 12 m.p.h., When its useful 10,000 lb. tractive effort is no longer needed. The gear ratio is about 2½ to one, and it is cut in or out by pneumatic mechanism.

Mechanical stoking is relied on, as the fire-box is far too big to make hand-firing possible. A 2-cylinder engine in the tender drives a worm-conveyor that brings the coal to a shelf just below the fire-door, where it is caught up by five steam jets that spray it into the four corners and centre of the box. The quantity fed is regulated by the speed of the conveyor, and its evenness on the grate by the jets, and by a deflector that can direct it more or less to either side. The stoker is indispensable on these large engines, and does far better work than it is possible for the most skilful fireman to achieve by hand.

The Westinghouse brake and a Walschaerts valve-gear are fitted, and the boiler is domeless, a collective dry-pipe being substituted. Domes have been given up by the C.P.R., except in mountain territory, where steep gradients may affect the boiler water-level, and results in water being carried over into the cylinders. These are 22 in. by 30 in. The driving wheels are 6 ft. 3 in. In diameter, and the tractive effort, with booster, is 57,250 lb. The boiler and fire-box are large, with a heating surface of about 5,000 sq. ft., A grate area of 81 sq. ft., and a working pressure of 275 lb. The driving axles carry 84 tons out of a total engine-weight of 163, and together with a tender carrying 21 tons of coal, and weighing 130 tons, the combined total becomes 293 tons.

Following a couple of days resting up in Fort William after a somewhat strenuous run of 24 hours and 792 miles from Toronto, most of it done in the cab of No. 2839, an engine similar to No. 2850, I made arrangements to carry on with the same train No. 3, “The Dominion,” to Winnipeg. It pulls out at 10.05 p.m., after a 20-minute stop, and I was down at the Depot in good time. After introducing myself to the engineer (driver, in English), who was going round the engine with lamp and oil-can, I climbed into the cab to make myself known to the fireman. We were all getting on a friendly footing and settling down nicely, momentarily expecting to hear the air-signal from the conductor (guard) to sound, when an official climbed into the cab and messed everything up. “Say, she’s running in two sections to-night - this is the first, with only six cars on, just mail and baggage. You’d better wait for the second; its got a diner and sleepers, and is much heavier. This outfit’s no good to you—you want to see an engine work.” So down I had to get, with expressions of regret from the crew. I was left to wait the arrival of the second section which turned out to be so heavy that it had to be a “double-header,” with a “Pacific” in front and to my gratification. No. 2850, the famous Royal engine, on the train. A second round of introductions made, I found myself installed in the cab with Engineer Robertson and Fireman Miller.

We pulled out at 11.27 p.m., into a night black as a pocket, the darkness occasionally lit up by lightning flashes. And now I am making a little confession - I have to admit I cannot remember whether No. 2850 had a booster or not! During the Royal tour she certainly had, but it may have been removed since, as all the class do not carry them. However, it does not matter much; I have described the booster, and if you like to think it was there, well and good.

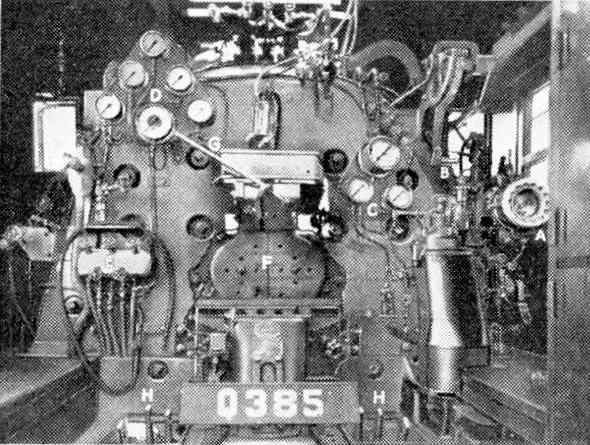

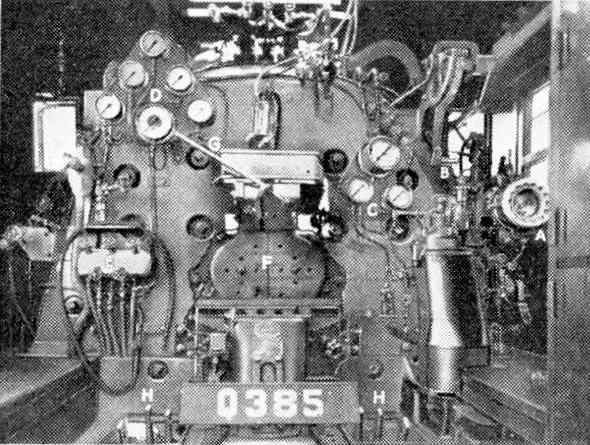

CAB OF A C.P.R. 2800 H1d “Hudson” class locomotive.

A few words about the cab and its fittings. The photograph above shows most of them; the engineer’s are on the right and the fireman’s on the left. The wheel with the serrated rim (A) is the reverse, air-operated. No effort is needed to work it, the little handle above it does the trick, and with a whirr the wheel spins, and the gear shoots forward or back, as required. Full valve-travel, from end to end, takes but couple of seconds. The throttle lever (B) hangs down from overhead, and is held in any position by catch and ratchet. To the left of the reverse are (C) brake controls, the gauges showing steam and exhaust pressure, and the brake dials. On the fireman’s side are gauges (D) showing s team-pressure, steam heat, stoker-engine pressure, feedwater pressure, etc. To the left of the fire-door are five little wheels (E) controlling the steam jets that blow the coal into the fire-box. The “butterfly” fire-door (F) is divided, hinged at the top, and opened by a pneumatic treadle; the long lever pointing to the left (G) holds the door open if necessary, otherwise it shuts when the fireman’s foot leaves the treadle.

The cab is very well arranged and comfortable, and entirely enclosed, There are three seats, the engineer's being hidden by the locker on the right; the fireman’s is out of the picture, as is also the third, used by the head brakeman when a freight train is being hauled, or by intruders such as myself. The cab is electrically lit by a lamp in the roof, round which is a shield with slots cut in it, through which pencils of light are projected on to the dials, quite obviating dazzle.

We have got under way by this time, with rapid acceleration, resulting from the two engines—or the booster, if it was there! The train was heavy, probably over 1,000 tons. The heavy, continuous up-grade makes it necessary for both engines to pull their socks up, if I may be allowed the expression, but that dues not mean the fireman has to work correspondingly hard, as would be the case on a hand-fired engine. Miller merely looks through the inspection-holes into the whirling white flames in the firebox, and occasionally turns the little jet-wheels, or perhaps gives the stoker-engine more steam. Through these holes you can see the coal coming on to a shelf just below the fire-door, to be caught up by the invisible steam jets and sprayed in an arching shower on to its flaming bed. It bursts into flame as soon as it leaves the shelf, and is largely burned in the air as it falls. The throttle was about two-thirds open, and the cut-off 35 per cent.

The riding of the engine was very good, and the track also was well cared-for. The 4-wheel trailing truck on these “Hudson” engines makes for easy action on the track. It is pivoted to a stretcher between the frames behind the rear pair of drivers. Being a double-header, most of the responsibility for our safe-conduct devolved upon the other crew, and that left it open to Robertson and Miller to relax a little, and chat.

So No. 2850 roared on through the night to the first stop, for coal and water, at Raith, 53 miles from Fort William, which was made at 1.03 a.m.; the average speed had been 33 mp.h. It does not sound much, but the whole stretch had been on a heavy up-grade, and the load, in spite of the two engines, no flea-bite. Besides, it was all the schedule called for—we were not out to break records. The “Pacific” came off here, leaving No. 2850 to carry on alone, and this it did, at 1.13 a.m.

During the run the grate had been rocked once or twice by a long detachable lever fitted over three stubs (H) that can be seen on each side of the floor in the photograph of the cab. They are lettered to indicate back, front, and centre, as the grate is in three sections. This breaks up clinker, much of which, with ash, drops through into the ash-pan, a much better way of getting rid of it than lifting it out through the fire-door with a long-handled shovel.

Ignace, a Divisional point, 147 miles from Fort William, was reached at 3.05 a.m., and here we all left the engine; Robertson and Miller to “turn around” and I to go back to the train and get some sleep.

The jarring of the brakes woke me up at 6.52— Kenora. I scrambled into my clothes, and made a dash for the engine, but there was no need to hurry; the “ground crew” was at work, taking out the ash-pan, using grease-guns and wrenches on the motion, etc., and the stop extended to nearly 20 minutes. “The Dominion” got away at 7.10, in the beauty of a perfect spring morning. No. 2850 thrashed along past lakes and rocky out-crops, through forests of fir and birch, past lonely “pioneer” farms isolated like oases in the wilderness that extends without a break to the Arctic.

It is double track to Winnipeg, the old original line being used for westbound traffic, so we were on it. When the line was duplicated, chiefly because of the tremendous Autumn wheat movement to Fort Witham, the new pair of rails were better located, with far easier grades. This solves the puzzle I mentioned a little way back why eastbound trains a have better grades than westbound ones. We had made stops at Keewatin and Ingolf, and now halted again at Whitemouth, our last port of call before Winnipeg, and took water. Rocks and lakes had been left behind, and the track no longer twisted and turned, but stretched ahead straight and level. We were entering the prairie, that lay like a vast 900 mile wide wheatfield, extending right to the foothills of the Rockies. So far, the left-hand track had been followed from Fort William, but now a “fly-over” took us across the eastbound track, to put us on the usual right-hand side when the two lines came together again. They had often been out of sight of each other for long distances. The country still showed many trees, but it was dead level. Soon we saw outlined ahead the tall buildings and factory chimneys of Winnipeg. In a few minutes we were entering it, and with her bell clanging, No. 2850 clattered over crossings and switches into the Depot, coming to a stand at 10.20 a.m., dead on time. “The Dominion" was half-way across the continent, and 419 miles west of Fort William, the distance having been covered in 10 hours 53 minutes, at an average speed of 38.5 m.p.h., in spite of half-a-dozen stops. However I discovered I must have forgotten to put my watch back one hour at Fort William, so all the times given in this article are an hour fast! To make them fit the C.P.R. timetable, we left at 10.27 p.m. and arrived at Winnipeg 9.20 a.m., but as this leaves the speeds mentioned unaffected, it does not matter. Distances in America are big; watches have to be put back four times when you cross the continent going and sometimes one forgets!

You can read more on “The Canadian Pacific Railway”, “The Doorway to Canada” and “The International Limited” on this website.

You can read more on “Canada’s Streamlined Engines” in Wonders of World Engineering