© Railway Wonders of the World 2024 | Contents | Site Map | Contact Us | Cookie Policy

The Canadian Pacific Railway - 1

The story of the great tanscontinental line which in parts cost £140,000 per mile

RAILWAYS OF THE COMMONWEALTH -

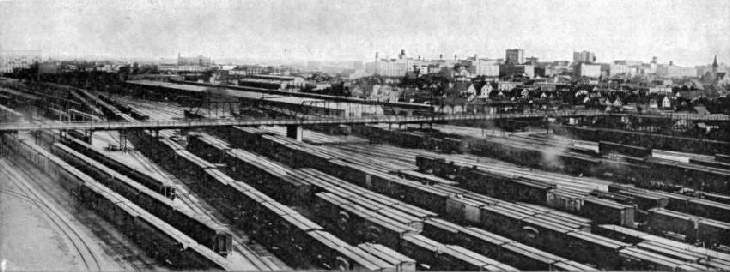

THE LARGEST INDIVIDUAL RAILWAY YARD IN THE WORLD. A part of the 120 miles of sidings belonging to the CPR at Winnipeg.

HALF a century ago the vast stretch of territory forming British North America was a heterogeneous collection of provinces, each of which virtually was a little kingdom in itself. Consequently there was an absolute lack of cohesive working: Canada presented a striking picture of a country divided against itself. And this was by no means the worst feature of the situation. On the Pacific seaboard was a flourishing colony, British Columbia, which not only was cut off from the other prosperous corners of Canada, but was also isolated from the Mother Country. In those days a journey to Vancouver was not to be undertaken lightly. If approached by water from England it involved a journey halfway round the world, and circuitous at that, since the vessel had to turn the southern extremity of the American Continent. On the other hand, the overland journey was just as forbidding, and quite as lengthy, because one had to toil afoot from the head of the Great Lakes over the prairies and across towering mountain ranges before the seaboard was gained.

British Columbia was handicapped by this isolation, so when a scheme was adumbrated to federate the various provinces the Pacific colony resolved to profit from co-

The advocates of federation were staggered by this ultimatum. Why, west of the Great Lakes stretched a wilderness to the feet of the Rocky Mountains, and then as unkempt and as wild a stretch of rugged country to the Western Sea as could be conceived! The whole country was in the melting-

tangled fabric together, here was one of the possible parties to the solution of a vexatious problem stipulating that a railway some 3,000 miles in length should be the price of its assistance. The terms were exacting. But British Columbia stood firm: a railway, or we stand aloof.

This was in 1871. Sir John Macdonald had formulated the confederation project, and he was determined to spare no effort to bring his pet idea to fruition. But this railway was a stumbling-

Fleming rallied his forces and drove his way steadily across the full breadth of the continent. Fortunately he was not handi-

There being no maps to guide him, young Fleming did the next best thing. He sought assistance from the Hudson Bay Company, whose men knew the western trails intimately, as they had to pack provisions overland to the Vancouver outpost.

It was a long trail which he drove from Montreal through Ontario’s timber and rugged fastnesses to Winnipeg, then Fort Garry, the Hudson Bay trading post. He struck westwards to Edmonton, and a few miles beyond picked up Thompson’s historic trek down the Athabasca River into the heart of the Rockies. Then he swung up the Miette River valley, crossed into British Columbia at the low altitude of 3,720 feet, dropped down the western slope of the Rockies, picked up the Fraser River, skirted Mount Robson, the twentieth century showpiece of the Dominion, gained Tete Jaune Cache, bore to the south-

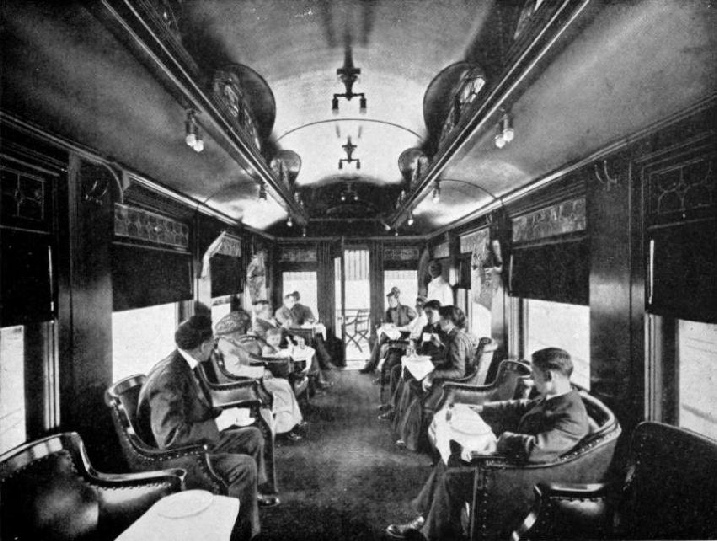

THE IMPERIAL LIMITED. This CPR Transcontinental Express runs direct between Montreal and Vancouver, 2,898 miles. The engine is changed about twenty times during the journey.

In addition to this route ten other reconnaissances were run through the Rocky Mountains, in which quest Charles Moberly, a kindred born railway pathfinder, played a very prominent part. Yet when the results were compared it was found that the Fleming preliminary was the easiest and obvious path for the transcontinental steel highway. That was way back in 1872, and yet when I followed in his tracks forty years later I still found some of his location and bench marks buried in the dense Canadian undergrowth.

But Fleming’s survey was not accepted. Thirty years were doomed to pass before its value became appreciated, when one new transcontinental railway actually followed his route through the mountain barrier. This is the Canadian Northern, as related in another chapter.

In the meantime the project had become the sport of party jealousy and strife, with the result that little was done. Although Sir John Macdonald had promised that the line should be completed by 1881, the end of 1879 saw the completion of only a paltry 713 miles. This procrastination provoked British Columbia. In blunt language it reminded the Dominion Government about its compact, and threatened drastic action if the bargain were not fulfilled instantly. Thereupon the Government swung to the opposite extreme. Dilatory tactics gave way to feverish haste. A syndicate comprising influential financial and technical interests expressed a willingness to take over the Government’s responsibilities, and to fulfil the official obligations to the satisfaction of British Columbia on terms which were set out specifically.

In the meantime the project had become the sport of party jealousy and strife, with the result that little was done. Although Sir John Macdonald had promised that the line should be completed by 1881, the end of 1879 saw the completion of only a paltry 713 miles. This procrastination provoked British Columbia. In blunt language it reminded the Dominion Government about its compact, and threatened drastic action if the bargain were not fulfilled instantly. Thereupon the Government swung to the opposite extreme. Dilatory tactics gave way to feverish haste. A syndicate comprising influential financial and technical interests expressed a willingness to take over the Government’s responsibilities, and to fulfil the official obligations to the satisfaction of British Columbia on terms which were set out specifically.

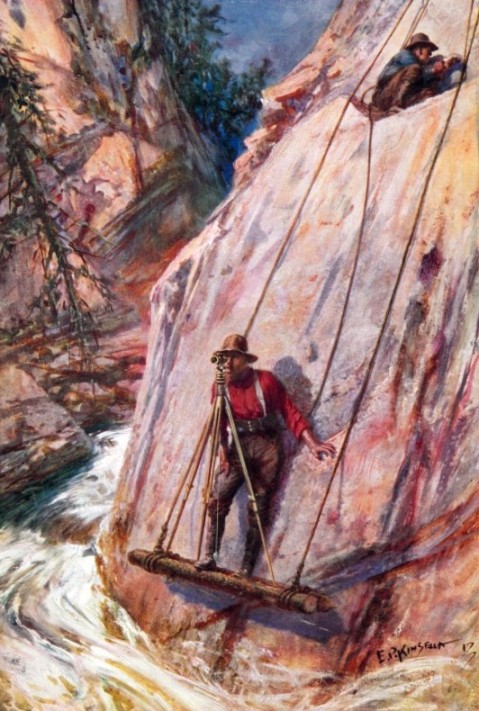

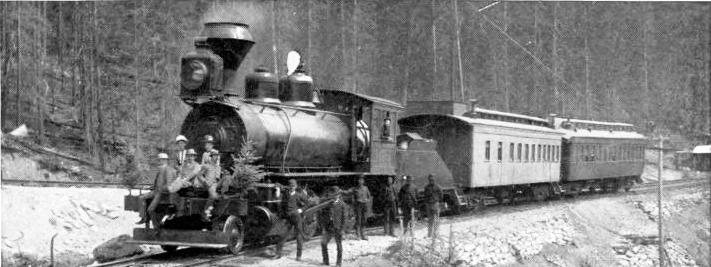

THE RAILWAY PATHFINDER. In searching for a route through rugged mountainous country the main with the transit and level often has to be slung on a crazy log platform over a raging torrent.

The Federal Government, pressed by the Pacific province, was caught at a disadvantage. The syndicate terms were exacting: -

Work was commenced forthwith and went ahead with a swing until the funds to defray construction ran out. A crash appeared to be inevitable. The London market resolutely refused to advance a single penny towards the enterprise. In desperation the company turned to the Dominion Government, which granted a loan of £6,000,000 upon what hostile critics declared to be a lost cause.

Although probably never in the history of railways has a constructional proposal been treated so liberally, possibly no enterprise so large ever experienced so many vicissitudes. The company, confronted with the necessity of maintaining an average advance of 250 miles per year in order to meet the time limit, toiled unceasingly to keep things going by hook or by crook. Disputes were frequent; threats among the subcontractors to “chuck the job” were heard on every hand; work was scamped at places; while at other points the engineers were worried out of their wits over the cheap and speedy solution of exasperating technical problems. Nor was the financial aspect free from anxiety: harassing questions arose at every turn. The inside history of the Canadian Pacific Railway never has been written, but when it is recorded it will be found to reveal a persistent and continuous stubborn struggle against threatening disaster.

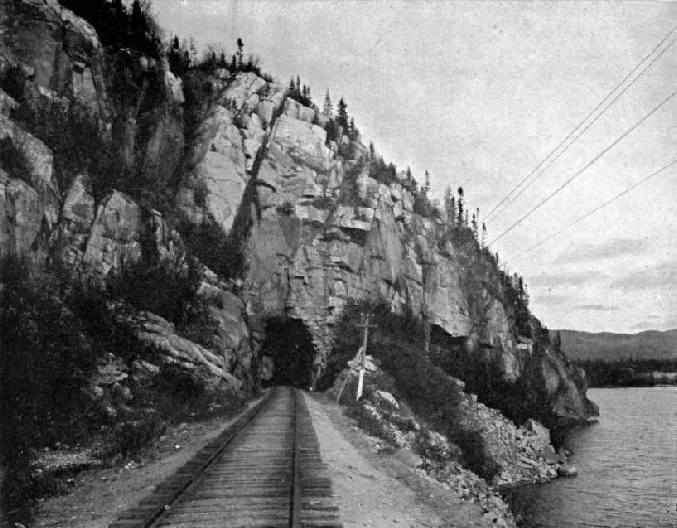

RED SUCKER TUNNEL ON THE LAKE SUPERIOR SECTION OF THE CANADIAN PACIFIC RAILWAY.

Fortunately men were found capable of grappling with ominous situations. Among these were Sir William Van Horne on the engineering, and Lords Strathcona and Mountstephen on the financial sides. By prodigious effort they kept construction going, although at times they were somewhat downcast by the outlook, especially in regard to the “sinews of war”. Labour, as usual, brought its manifold troubles. Railway expansion was active in the United States, where high pay was to be earned, so that Canada held out no tempting inducements. The majority of the graders regarded work upon the Canadian enterprise in the light of a holiday, or a timely change of air and scenery. Many of the graders I know divided their time between the Canadian Pacific, Northern Pacific, and other American lines; they could not be tempted to stay upon one job more than a month or two on end.

The builders were forced to realise the magnitude of their task in the first stretch between Montreal and Port Arthur. South-

The surveyors were forced to take to the shore of the lake, and as a result a gallery had to be blasted out of the sombre granite, mica, schist, and black trap, a few feet above the water level, driving through the projecting lofty promontories and crossing the little bays, some of which were filled with the dislodged rock from the cuts and tunnels, while others were bridged. The rock was dense and put up a stern resistance: nothing but black powder and dynamite could cope with it. Under these circumstances it is not surprising that a mere stretch of 200 miles through Southern Ontario cost about £2,500,000, while at one or two places the cost ran as high as £110,000 per mile.

A LIBRARY-

The region of Lake Superior has been described as the coldest and bleakest part of Canada, and the graders who had heard of this unsavoury reputation had occasion to remember that for once rumour did not lie. In fact, many of them, after the experience of a week or two, threw down their tools and departed to seek work in a more congenial clime. Camp comforts in those days were unknown, the commissariat was not so abundant or varied as the canning factories have made it today. The food in the winter was despairingly monotonous, and truly backwoods in character. “Mush” -

The sprawling muskegs of Southern Ontario were just as teasing and maddening as the hard rock. Every possible device for subjugating the bog was tried and found wanting. One muskeg, in particular, nearly drove the graders and engineers frantic. It swallowed rock and spoil by the thousands of tons, and timber corduroy by the hundreds of feet. Yet the embankment refused to become permanent. At last the engineers did succeed in getting a road; then the railway operators were given a taste of the bog’s treachery and fickleness. It was just as if the permanent way had been laid upon a bank of resilient indiarubber. As the train passed over the road-

From Port Arthur the line was driven through the heavily timbered and water-

You can read more on “The Canadian Pacific Railway 2”, “The Conquest of Canada”, “The Doorway to Canada” and “The Opening up of Canada” on this website.