High-Speed Runs on Railways

Great Western Railway No. 3440 “City of Truro”, for which a speed of 102½ mph was claimed, but not authenticated, in 1904.

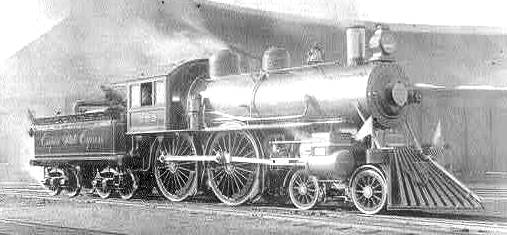

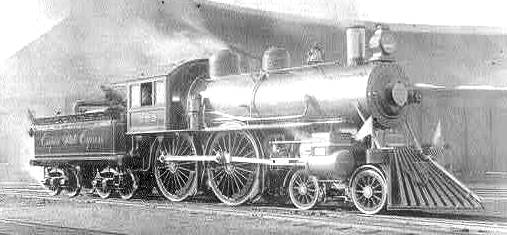

IN the final decade of the nineteenth century the first claim was made to have reached a three-figure speed on rails in the United States of America. The claim was followed during the next few years by others from the USA and although some have subsequently become almost legendary, they are supported by little or no acceptable evidence and cannot therefore be regarded as authentic.

One claim was that in May 1893, 4-4-0 No. 999 of the New York Central Railroad, with coupled wheels of the unusually large diameter of 7 ft 2-in, worked the four-coach Empire State Express up to a maximum of 112½ mph between Rochester and Buffalo. A second was that in June 1905, Pennsylvania Railroad 4-4-2 No. 7002, at the head of the New York-Chicago Pennsylvania Special, when recovering lost time, touched 127·7mph at a point just west of Lima. In both cases such times as were quoted were only to the nearest minute over quite short distances, and could not be regarded as evidence of any value. A third was the ludicrous claim that in 1901, after the failure of a locomotive heading the Florida Mail of the then Plant system (now the Atlantic Coast Line), an engine commandeered from a freight train ran the last 5 miles to a dead stop at Jacksonville in 2½ minutes, at 120 mph!

Apart from the fact that none of these claims had the support of a detailed log, including exact passing times, it is impossible to imagine that at that early date the technique of locomotive valve-setting and front-end design generally had progressed sufficiently to permit a steam locomotive to use, and particularly to exhaust, its steam with such rapidity as to make possible a speed as high as two miles a minute, and that without advantage of gradient.

Meantime, however, some well-authenticated speeds of over 100 mph had been attained on experimental runs in Germany, but with electric power. In 1901 the firm of Siemens & Halske had developed a double-bogie electric locomotive, and on a track laid down specially for test purposes between Marienfelde and Zossen, near Berlin, achieved in that year a maximum speed of 101 mph. By 1903 two 50-seat electric motor-coaches had been built, and both were worked up to a top speed of 130 mph. Current was collected from overhead conductors at 15kV AC. This remained the officially recognised record speed on rails until the 143 mph maximum attained by the Kruckenberg airscrew-driven diesel car in 1931, as described already in an earlier chapter of this work in an article on the “Flying Hamburger”.

Returning to steam, we come to the year 1904, when a maximum speed of 102½ mph was claimed for 4-4-0 locomotive No. 3440 “City of Truro” of the Great Western Railway when descending the 1 in 81-90 of Wellington bank, just west of Taunton, with a train of five mailvans weighing 148 tons. But here again, owing to certain contradictions in the figures left by the recorder, Charles Rous-Marten, and to inaccuracies in certain other of his published logs, the record cannot be accepted as authentic. It seems unlikely, indeed, that the highest speed exceeded 97 mph.

New York Central Railroad No. 999 was the subject of a non-authenticated speed claim in 1893, of 112½ mph.

Thirty years elapsed before another British claim was made of a speed with a steam locomotive at the three-figure level, and it was authenticated by the inerrant record of a dynamometer car. The train was a six-coach special from Leeds to Kings Cross, London & North Eastern Railway, on November 30, 1934; it weighed 207½ tons and was headed by Gresley Pacific No. 4472 “Flying Scotsman”, of the then LNER Class A1. The peak speed was reached at milepost 91, midway between Little Bytham and Essendine, after a descent of 3 miles at 1 in 178, a mile level, and 4½ miles down at 1 in 200. The dynamometer record showed 100 mph sustained for a distance of 600 yards. Both this test and a subsequent one between Kings Cross and Newcastle-on-Tyne, on March 5, 1935, were in preparation for the introduction of the Silver Jubilee streamlined train in the autumn of 1935.

On the latter test run Gresley Class A3 Pacific No. 2750 “Papyrus” was the engine, with a six-coach train of 217 tons. At precisely the same location as on the previous test, “Papyrus” maintained a speed of 108 mph for 10 seconds, as part of an average of 100·6 mph kept up for 12·3 miles continuously, from Corby Glen to Tallington. During the descent, steam cut-off on the engine was advanced gradually from 22 to 32 per cent, with the regulator full open; boiler pressure was maintained steadily at from 200 to 215 lb sq. in., and steam-chest pressure at 150 to 160 lb, which was later sufficient for a continued 100 mph on but little easier than level track beyond Tallington.

These two records were the curtain-raiser to the trial trip of the Silver Jubilee itself, on September 27, 1935. On this the new streamlined A4 Pacific “Silver Link” covered the 25 miles between mileposts 30 and 55 out of King’s Cross at an average speed of 107·5mph, during the whole of which speed was above 100 mph and twice reached a peak of 112½ mph, at Arlesey and between Biggleswade and Sandy. The acceleration to the first 112½ mph began down 1 in 200-264, but from Biggleswade onwards from 105 to 112½ mph was being kept up continuously on practically level track with a seven-coach load of 220 tons tare and 230 tons gross. The 41·2 miles from Hatfield to Huntingdon, including a slack to 85 mph for the Offord curves, were covered at an average of 100·6 mph, and the total distance run at a mean speed of 100 mph was 43 miles.

The next LNER test was on August 27, 1936, when the dynamometer car was attached to the up Silver Jubilee train, and on the customary racing stretch down from Stoke Summit, with eight coaches of 254 tons tare and 270 tons gross, A4 Pacific No. 2512 “Silver Fox” fractionally exceeded “Silver Link’s” record by touching 113 mph near Essendine. A further LNER maximum speed of note was on the trial trip of the Coronation streamlined train, on June 30, 1937, when with a considerably heavier nine-coach load of 312 tons tare and 330 tons gross A4 Pacific No. 4489 “Dominion of Canada” attained 109½ mph on the descent from Stoke.

On the previous day, June 29, 1937, another British railway achieved a three-figure speed record. This was the London Midland & Scottish, and the occasion was the trial trip of its competing Coronation Scot train from Euston to Crewe. The eight-coach train set, of 263 tons tare and 270 tons gross, was headed by Stanier’s new streamlined Pacific No. 6220 “Coronation”, and the LMSR authorities were determined, if they could, to beat the existing LNER record speed of 113 mph. For this attempt the assistance of gravity was needed, and the only location where the inclination was sufficient to give the needed help was the descent at 1 in 348-177-269 in the final 10½ miles from Whitmore to Crewe.

There the driver succeeded in working No. 6220 up to 114 mph, and so to 1 mph above the LNER maximum. But this maximum was reached at milepost 156, only 2 miles from Crewe, and so near that disaster was but narrowly averted when, after hard braking, speed was still 57 mph as the train reached the first of the crossover roads leading into Crewe station. Mercifully neither engine nor train suffered any damage, as was proved when on the return journey “Coronation” just touched the 100 mph mark down the 1 in 330-410-326 gradient from Roade to Castlethorpe.

On July 3, 1938, however, the LNER supremacy was put in no doubt by the Gresley A4 pacific No. 4468 “Mallard”, as the climax to a series of tests connected with the braking of high-speed trains. With a seven-coach load of 237 tons tare and 240 tons gross, when descending from Stoke Summit towards Peterborough, “Mallard” reached a top speed, verified by the dynamometer record, of no less than 126 mph. The summit box was passed at 74½ mph; from there, with the regulator full open and cut-off at 40 per cent, speed rose in 3 miles down 1 in 178 to 104 mph at Corby Glen, followed by an increase to 110 mph on 1½ miles of level track. From milepost 94¾ to milepost 93 the driver experimented with 45 per cent cut-off, speed rising to 119 mph, but he then linked up to 40 per cent, still with full regulator, and at the foot of the 4½ miles at 1 in 200 down from milepost 95½ 124½ mph had been attained.

LNER No. 4489 Gresley streamliner “Mallard” which did 126 mph in July 1938.

On the broken grades that followed the dynamometer car registered an absolute maximum of 126 mph for a short distance. Between mileposts 94 and 89 (steam was shut off at milepost 89¾ to ease the speed round a slight curve at Essendine) 5 miles were covered in 2 minutes 29½ seconds, at an average of 120·4 mph, and speed was actually at or above the 120 mph mark for the 3 miles between mileposts 92¾ and 89¾. So far as is known from properly authenticated records. “Mallard’s” 126 mph is the highest speed that has been reached by steam power in any part of the world.

It is of interest to note what developments had taken place in the design of the Gresley Pacifics of the London & North Eastern Railway between the attainment of the first 100 mph by “Flying Scotsman” in 1934 and of 126 mph by “Mallard” in 1938. With the improved valve-setting that resulted from the exchange in 1925 of an engine of this type with a Great Western Castle class 4-6-0, “Flying Scotsman” still retained its original 6 ft 8-in coupled wheels, 20-in by 26-in cylinders, and 180 lb. sq. in. working pressure. The Class A3 “Papyrus”, which pushed the record up from 100 to 108 mph, had a boiler carrying 220 lb pressure, and cylinders reduced in diameter from 20-in to 19-in, though still with 26-in stroke.

With the A4 Pacific “Silver Link”, which achieved 25 miles continuously at over 100 mph and a maximum of 112½ mph, later fractionally increased by “Silver Fox” to 113 mph, there had been a further reduction in cylinder diameter to 18½-in, but an increase in boiler pressure to 250 lb, coupled with a careful streamlining of the steam passages. Finally “Mallard”, which raised the top speed substantially to 126 mph, had the advantage of a double blastpipe and double chimney, with consequent assistance both to draught and to freedom of exhaust.

The nearest known approach by steam power to “Mallard’s” 126 mph was 124½ mph attained in 1938 by the German streamlined 4-6-4 No. 05.001 on an experimental run between Berlin and Hamburg, which would be on level track, but no details were made public as to the weight of the train or the precise location where maximum speed was attained. Something approaching the same figure was attained by a sister engine of the same type, No. 05.002, when a three-coach 142-ton special train conveying a party of the Institution of Locomotive Engineers, from Berlin to Hamburg, on May 30, 1936, attained a top speed of 118 mph between Wittenberge and Ludwigslust. But neither in Germany nor in Great Britain have there been at any time any schedules which required speeds of up to 100 mph for timekeeping with steam power. Many have been Gresley Pacifics of the LNER; Great Western “Castle” class 4-6-0s have attained up to 102½ mph when descending the long 1 in 300 from Badminton; 110 mph has been claimed for a GWR “King” class 4-6-0 with double blastpipe and double chimney, but the evidence for this was inconclusive. On the LMSR a “Royal Scot” 4-6-0 has been timed at up to 100 mph on the long 1 in 200 descent of the Midland main line towards Bedford.

The LMSR competitor in speed. No. 6220 streamlined Stanier Pacific “Coronation”, which took the British record from the LNER in June 1937 for about a year, with 114 mph.

The only railway in the world which has ever brought into operation schedules demanding 100 mph speeds with steam power has been the Chicago, Milwaukee & Pacific Railroad. In 1935 the company introduced a streamlined express called the “Hiawatha” between Chicago, St Paul and Minneapolis timed to cover the 410 miles in 6½ hours, inclusive of six intermediate stops and 58 speed restrictions of varying severity.

For its haulage the company built the world’s most powerful “Atlantics”, with 7 ft coupled wheels, 19-in by 28-in cylinders and 300 lb pressure. One of them has been timed to cover 12 miles between Chicago and Milwaukee at between 97 and 106 mph, with the engine cutting off at 28 per cent, and 280 lb pressure in the steam-chest out of 295 lb steadily maintained in the boiler.

Patronage of the train then grew to such an extent that the original nine cars had to be increased to twelve, of 550 tons weight, and for their haulage a magnificent new coal-burning 4-6-4 locomotive class was brought into service. It was found that with one of these 4-6-4s 105 mph could be attained on level track on 25 per cent cut-off, and with the regulator no wider open than to give a steam-chest pressure of 150 lb. sq. in. out of the 300 lb boiler pressure. As with the 4-4-2s, coupled wheels were 7 ft in diameter, but the cylinders were enlarged to 23½-in by 30-in. On one occasion in 1942 No. 101 of this class, with no fewer than 14 coaches of 680 tons weight, covered 48 miles of the Chicago-Milwaukee run at an average of 105·4 mph. The highest speed ever recorded with a “F7” class 4-6-4 was 125 mph (just short of “Mallard’s” record) on which occasion a mean speed of 120 mph was kept up over 4½ miles of level track.

One of the most remarkable three-figure maxima ever achieved with steam power was the 110 mph of a “J” class 4-8-4 of the Norfolk & Western Railway - astonishing because this was with eight-coupled wheels of only 5 ft 10-in nominal diameter, reduced by tyre wear to 5 ft 8½-in. This would have entailed a maximum piston speed of 2,878 ft/minute, which probably has been exceeded on one occasion only in railway history. This was when the American New York Central System was investigating the balancing of its “J3” class 4-6-4 express engines, and deliberately slipped the driving wheels of one of them on greased rails to an equivalent speed of 164 mph. Such a speed involved a maximum piston speed of 3,370 ft/minute, and 11·6 revolutions per second of its 6 ft 7-in coupled wheels.

Norfolk & Western Railway “J” Class 4-8-4.

You can read more on “108mph on the LNER”, “New Speed Records on the LNER”, “The Silver Jubilee” and “Speed Trains of Britain” on this website.