Some huge American and Canadian locomotives driven by electricity

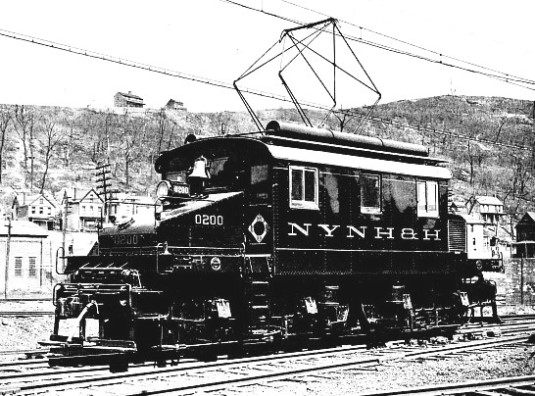

THE 1,000 HORSE-POWER 0-4-4-0 ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE OF THE NEW YORK, NEW HAVEN

AND HARTFORD RAILWAY. This type is employed for heavy express passenger service, and with a maximum load can attain 50 miles per hour.

WHILE remarkable progress has been effected in Europe in regard to the application of electricity for haulage purposes in connection with main line working, it is in the United States and Canada where the greatest strides have been made. Curious conditions such as do not prevail in these islands have brought about this supersession of steam.

Some of these developments, such as the adoption of electricity upon the New York Central and Hudson River Railway, and also the electrification of the Cascade Tunnel of the Great Northern Railway, have shown that the utilisation of steam handicapped the lines concerned very appreciably.

Therewith the traffic capacity had attained its limit. Accordingly the roads either had to resort to electricity so as to increase the limit of the existing facilities, or were faced with the expensive alternative of providing additional tracks.

In both cases the latter was considered to be a premature solution of the problem. The Cascade Tunnel was merely an incident in trans-continental travel, and was called upon to cope with through traffic only. In the other instance a congested terminal and its requirements had to be studied. When the New York Central penetrated the Empire City of the Empire State, the former was relatively small and confined to the lower part of Manhattan Island. The directors of the railway failed to grasp the salient fact that when the city commenced to grow it could expand in one direction only — northwards. Consequently they made no provision for the future by acquiring sufficient land for widenings and extensions. When the railway found itself hemmed in, and traffic so increased that the capacity of the line was reached under steam conditions, the engineers boldly recommended extensive electrification.

To-day no steam train runs in or out of the New York Central Station; electrical locomotives perform the whole of the haulage work, both for main line express passenger, goods, and local traffic. At a station outside the bottle-neck approach the incoming trains stop, the steam locomotives are uncoupled and the electric machines attached. Similarly upon the outward journey a pause is made at this point to exchange the electric for the steam engines. Owing to the length and weights of the trains huge electric locomotives of immense power have been acquired. The largest are of the 4-8-4 type, with the four pairs of driving wheels coupled, and weighing ready for the road 115 tons. The driving wheels have a diameter of 44 inches, the weight per axle being 17¾ tons. The locomotives measure 43 feet overall by 13¾ feet in extreme height, and the rated output of the four direct current motors with which each is equipped is 2,200 horse-power, giving a guaranteed speed of 75 miles per hour.

For moderate speed heavy passenger and freight service a somewhat smaller electric locomotive is used, varying from 90 to 100 tons on the driving wheels. These are designed for the very heaviest railway operation. As in the case of the other electric engines supplied to this railway, they were built at the Schenectady works of the General Electric Company. They are of the 0-4-4-0 articulated type with four motors each of 300 horse-power rating. The driving wheels are 48 inches in diameter, and at a speed of 12 miles per hour a tractive effort of 35,000 pounds is developed, while the maximum safe speed with the locomotive running light is from 35 to 40 miles per hour. Over 35 locomotives of this type are in service to-day, and this number is to be increased as the electrified zone is extended.

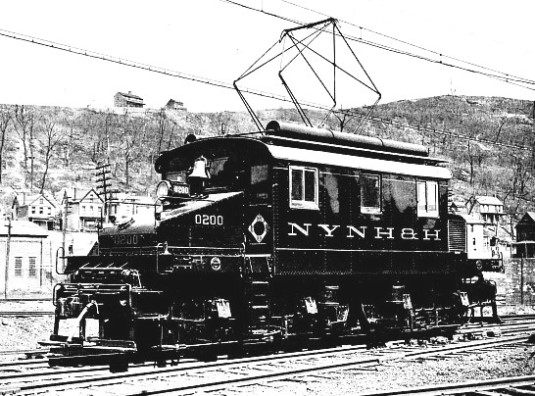

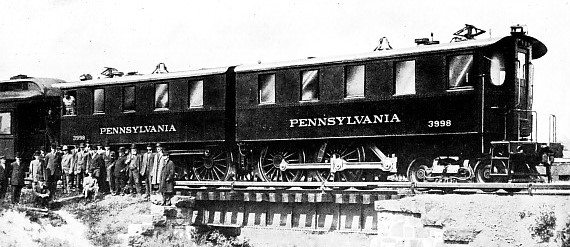

8O-TON 750 HORSE-POWER ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE OF THE NEW YORK, NEW HAVEN AND

HARTFORD RAILWAY. This type is used for shunting operations.

In the application of electricity to steam railways the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railway was among the pioneers, a section of 33·4 miles between New York City and Stamford, Conn., being converted thereto as a first instalment. As this system uses the Grand Central terminus of the New York Central and Hudson River Railway, and runs over their tracks for a distance of 12 miles, its locomotives are adapted to use the third rail direct system at 650 volts of the latter as well as the single-phase alternating overhead system at 11,000 volts of its own road.

The bulk of the traffic on this railway is operated electrically. The heavy express passenger trains are handled by engines rated at 1,000 horse-power, capable of attaining speeds up to 50 miles per hour. The heavy goods trains up to 1,500 tons load are hauled by 1,250 horse-power locomotives at a maximum speed of 35 miles per hour, while 800-ton passenger trains are also moved therewith, the contract speed in this instance being 50 miles per hour. Electric locomotives are employed for shunting operations upon the electrified division, these engines weighing 80 tons and developing 750 horse-power. Electrification having proved such a complete success upon this railway, 250 additional miles of track, including 63 miles of goods-yard sidings, are in course of conversion.

When the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada laid a single-track steel tube beneath the St. Clair River

to ensure a continuous rail journey between Chicago, Toronto, Montreal, and Portland, it was considered that a great problem had been solved completely. But within the course of a few years it was quite inadequate. Thereupon electrification was adopted, and it has met the situation very effectively. Electric locomotives, each consisting of two half-units, with each half-unit mounted on three pairs of driving axles, were designed. Each axle is driven through gearing by a 250 horse-power single-phase motor, so that the aggregate of the complete engine is 1,500 horse-power, capable of being increased up to 2,000 horse-power or even more if the exigencies demand. The engine weighs 135 tons, and it is designed to exert a draw-bar pull of 50,000 pounds at a speed of only 2 miles per hour. The locomotives are sufficiently powerful to start a train of 1,000 tons upon a bank of 1 in 50 if necessary, while the rated maximum speed is 35 miles per hour on the level and 12 miles per hour on the 1 in 50 grades of the approaches.

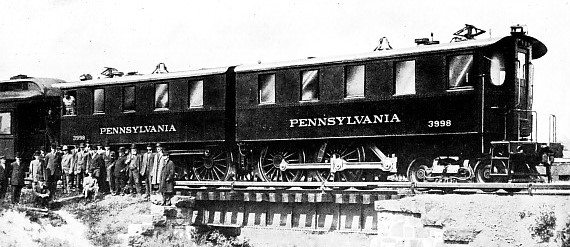

THE MAMMOTH 4,000 HORSE-POWER ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE HAULING A PENNSYLVANIA EXPRESS at 60 miles per hour across the Meadows just after leaving New York City.

Six locomotives were acquired for service, and they now make 25 trips each way through the tube per day. As compared with the former steam locomotives the electric machines can cover the 2¼ miles in a third less time, and this, with a 1,000 ton train, represents the passage of 6,000 tons instead of 4,000 tons per hour through the tube. Some idea of the efficiency and sound design and construction of these locomotives may be gathered from the fact that during the first two years of service each locomotive covered 70,000 miles without a breakdown, while during one round twelvemonth’s service there was but one delay to a train, and that only of eight minutes.

A long tunnel on the busy section of a big railway is a severe stumbling-block. It not only strangles traffic, but safety in travelling is imperilled. The Boston and Maine Railroad discovered this fact in regard to the Hoosac Tunnel. This is the longest work of its character in the United States, being 25,081 feet from end to end. It pierces the Berkshire Hills lying between the Hoosac and the Deerfield Rivers. When the tunnel was laid out questions of drainage and adequate ventilation — the latter is always a troublesome factor in such undertakings — demanded close attention. The former requirement necessitated the provision of a gradient of 26·4 feet per mile from each portal to a short level stretch near the centre whereby all water is carried off. The ventilation problem was not solved so easily, although a ventilating shaft extends vertically from the centre through the hills above for a distance of 1,028 feet into the open air. Increasing traffic and the volume of steam discharged into the tunnel from locomotives struggling with heavily laden trains brought matters to a crisis. The service was increased until not another train could be put through the bore, while delays became frequent and serious owing to the drivers being forced to grope their way carefully through the smoke.

At last it was decided to ascertain what beneficial effects would arise from electrification, and this contract likewise was carried out by the Westinghouse Company. Nearly 8 miles of track, including the 4¾ miles of tunnel, were converted. At each end of the electrified zone yards are provided for the shunting and accommodation of the electric locomotives. Single-phase alternating current at 11,000 volts was installed, and the service was opened on May 27th, 1911, since which date all traffic has been moved electrically through the Hoosac Tunnel. The locomotives of the 2-4-4-2 articulated type are fitted with four 300-volt 25-cycle Westinghouse railway motors. The driving wheels have a diameter of 63 inches, and in running order the machine weighs 130 tons. The mechanical equipment was built at the Philadelphia shops of the Baldwin Company, the well-known builders of steam locomotives, this firm, realising the future of the electric rival, having co-operated with the Westinghouse Company in this particular development.

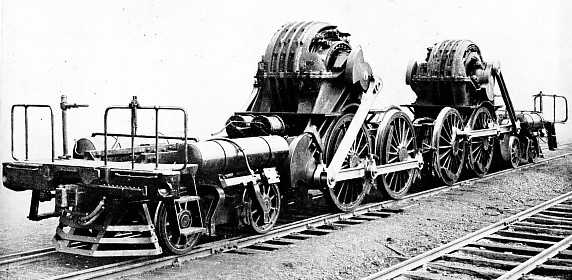

THE LARGEST AND MOST POWERFUL ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE IN THE WORLD. It develops 4,000-horse-power and is employed for hauling trains through the New York tubes of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company.

These Boston and Maine electric engines are designed primarily for freight service, although they are utilised for passenger train work also. From 60 to 70 trains of all descriptions are carried through the Hoosac Tunnel in this way every day. Unlike the practice adopted in connection with the Cascade, St. Clair, and other electrified tunnels, the steam locomotives are not detached and coupled up at the respective ends of the tunnels. Upon the arrival of a train at either of the electric junctions, the electric locomotive is attached to the front of the steam locomotive, and the latter passes through the bore with the steam shut off, resuming steaming when the opposite yard is reached, and the electric machine has been uncoupled. Goods trains up to 1,600 tons including the steam locomotive are hauled through in from 15 to 20 minutes, while the passenger trains, ranging from 400 to 500 tons in weight together with the steam locomotive, are able to negotiate the tunnel in 7 to 8 minutes. In this instance not only has electrification enabled heavier loads to be hauled and acceleration achieved, but it has also enabled the railway engineers to cope with the ventilation difficulty very effectively.

THE “INTERNATIONAL LIMITED” EMERGING FROM THE ST. CLAIR TUNNEL. By means of 1,500 horse-power electric locomotives a train weighing 1,000 tons can be hauled through the tube.

But the heaviest electric locomotives in daily operation at present in any part of the world are the Westinghouse mammoths employed by the Pennyslvania Railway to haul all trains under the Hudson and East Rivers between the New York City terminus and the Brooklyn and New Jersey shores. When this company decided to establish itself in the heart of the city it realised the indispensability of electric working through the connecting tubes. The prevailing gradients and the heavy long trains demanded enormous power, and the Westinghouse Company thereupon was urged to provide a machine capable of fulfilling any possible emergency that might arise.

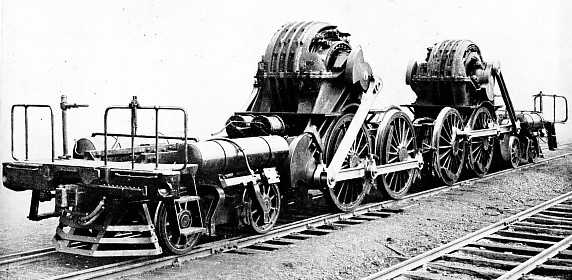

The outcome of prolonged experiments and investigations was the huge articulated 4-4-4-4 machines, 65 feet in length, and weighing 157 tons complete, capable of developing a maximum of 4,000 horse-power. These engines have drivers 72 inches in diameter with 50,000 pounds imposed on each axle, giving an aggregate adhesive weight of 200,000 pounds or 100 (U.S.) tons. The rigid wheel base of each half of the locomotive measures 7 feet 2 inches, while the total wheel base of each half is 23 feet 1 inch, and for the whole engine 55 feet 11 inches. The weight of each motor, including cranks, is 43,000 pounds. The contract called for a tractive effort of 60,000 pounds, and a normal speed, with full train load, of 60 miles per hour. In addition, owing to the severe grades in the tunnels, the locomotive had to be capable of starting and accelerating a train load on a bank of 1 in 50.

Under test the locomotive developed a maximum draw-bar pull of 79,200 pounds. These trains are called upon to perform very heavy duty, the average train entering and leaving New York City representing a dead weight of from 360 to 550 tons. The trial runs with this locomotive proving successful under peculiarly exacting conditions, an initial order for 24 such engines was placed with the designers, the mechanical equipment being built by the railway company itself at Juniata.

Although at the moment this 4,000 horsepower machine represents the heaviest and most powerful electric locomotive in the world, finality in this direction has by no means been reached.

THE MOTORS, EACH DEVELOPING 2,000 HORSE-POWER OF THE largest and most powerful

electric locomotive in the world.

You can read more on “Electric Locomotive Classification - 1”, “Some Electric Giants of Europe” and “Steam v. Electricity” on this website.