The development of electrical power has led to the production of some wonderful electrically driven locomotives

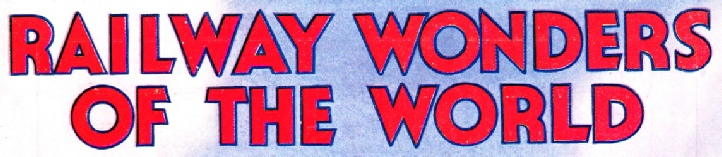

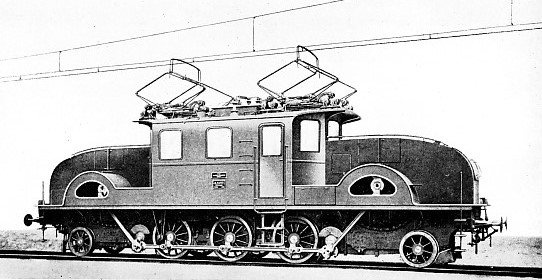

THE 2-6-2 ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE USED ON THE PRUSSIAN STATE RAILWAYS.

ALTHOUGH electric traction has not made very great strides in Great Britain in connection with main-line working [written in 1912], it has made remarkable headway upon the continent of Europe. This is particularly the case in those countries where economic conditions virtually have compelled such a movement. Italy, Scandinavia, and Switzerland arc almost exclusively dependent upon' foreign sources for all fuels; on the other hand, each has an abundance of water-power running to waste. It is not surprising, therefore, in the light of modern knowledge, that these countries should be devoting their energies to harnessing these sources of energy for the movement of traffic over their respective railway systems.

So far as Switzerland is concerned, and the same applies to Italy in a lesser degree, electric traction practically became a necessity to work traffic through the long Alpine tunnels. Steam operation is beset with many difficulties, not the least of which is the fouling of the tunnels by steam and smoke, while the problems attending ventilation in order to render the temperature within the tunnels tolerable to the travelling public became acute. True the St. Gotthard tunnel, which is the longest in the country, has been worked by steam ever since its opening, but only because there was no alternative. But the traffic of the Swiss railways has advanced by leaps and bounds until at last the St. Gotthard became taxed to its utmost capacity. The smoke trouble governed the situation; the tunnel became the limit of the line.

Consequently when the Simplon was taken in hand electrical manufacturers upon the Continent contemplated the feasibility of working it by electric traction. The Government had left the question open until the work was completed, or until electric traction had reached a more advanced stage, so that they might be in a position to view and discuss the problem more comprehensively and lucidly. But the manufacturers did not wait for completion; they formulated proposals for achieving the desired end in anticipation.

Among these firms was that of Messrs. Brown, Boveri, and Company, of Baden, Switzerland, a concern which, founded by an Englishman, has grown and spread its tentacles all over the world. In the autumn of 1906 this firm approached the Swiss Federal Railways with an offer to install a system of electric traction throughout the Simplon tunnel and railway, and to have it ready by the day the tunnel was opened to traffic. It was a big proposal, and in the light of contemporary knowledge was somewhat bold. Still, it was favourable from the Government’s point of view, inasmuch as the company undertook to complete the work at its own expense, and if it should prove a failure, would remove it. The Government therefore stood to lose nothing, since, even if things came to the worst, they could introduce steam working immediately, so that there need be no interruption of traffic.

At first sight such a bargain appeared to be one-sided; the company seemed to be facing a heavy risk. But against this contention had to be placed the circumstance that Brown, Boveri, and Company already had completed several notable electric railway undertakings, such as the Gornergrat rack, the Jungfrau, and the Burgdorf-Thun railways. Although none of these installations approached that contemplated for the Simplon in magnitude, still, they provided the contractors with valuable experience and a basis for completing the larger and more important work.

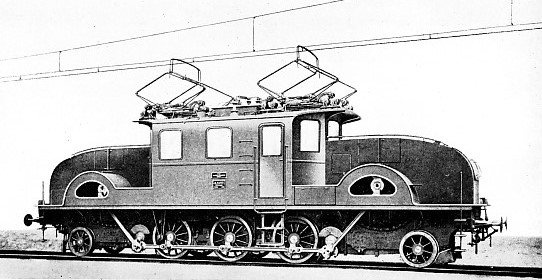

THE 1,250 HORSE-POWER 2-8-2 LOCOMOTIVE used on the Dessau-Bitterfeld Railway.

The Government discussed the offer, but although it appreciated the fact that a unique opportunity would be provided for the purposes of comparing steam and electric traction upon a large scale, it did not accept it finally until the end of the year 1905. This delayed acceptance was disadvantageous to the contractors, as the tunnel was approaching completion, and they would have to hasten to have their work completed on time. On the other hand it was a fortunate circumstance, inasmuch as no time could be afforded to discuss the merits of the relative systems. The company had more familiar experience with the three-phase system up to that date than with any other, so decided immediately to install it on the Simplon Railway.

The greatest anxiety arose in connection with the locomotives, but even this difficulty was overcome successfully. At the time the contractors had two three-phase 1,000 horse-power locomotives under construction for the Adriatic electric railways. So, in order to gain time, the Italian railway company was approached to ascertain whether it would waive its rights to these engines and allow them to be used on the Simplon line, the peculiar circumstances being explained. The Italian railway company readily consented to the proposal. The work of electrifying the tunnel was taken in hand without delay, and was pushed forward so satisfactorily that the installation was completed on time. In one respect the contractors had to make existing facilities serve their purpose. This was in regard to the power stations. The two water-power stations, at Brigue and Iselle respectively, which had been laid down to supply the machines used in boring the tunnel were utilised for this purpose, merely being modified to meet the new conditions. They were purely makeshifts and served their purposes very effectively, although their operation was far from being as reliable as was desired. Still, their temporary character was recognised, and it was appreciated that the defects which arose from time to time in connection therewith would be entirely overcome when a specially designed powerhouse was erected. These two stations supplied current at 3,300 volts, and a periodicity of 16 cycles per second, and fortunately the two locomotives under construction for the Italian railways had been designed for this pressure and frequency.

The locomotives, which were giants of their day, were of the bogie type, with five axles, three of which were driven, so that the machine coincided with the 2-6-2 Whyte numerical classification. The traction motors were placed between the three pairs of driving wheels, and both drove on the middle axle by means of a bar coupling them rigidly together. This axle in turn drove the other two by means of a coupling rod, so that gears were eliminated. The overall length of the locomotive was 40 feet 6 inches with a distance of 23 feet between the bogies, and 16 feet 1 inch between the driving axles. The driving wheels were 5 feet 4½ inches diameter, and the bogie wheels 2 feet 9½ inches in diameter. The total weight of the machine was 62 tons. Of this total 34 tons represented the mechanical section of the equipment, and 28 tons the electrical portion, while 42 tons were imposed on the driving wheels. The weight of each motor complete was lOf tons, and they were the lightest for their output which had been built up to that time. The normal rating of the two motors working together was 900 horsepower, with a maximum of 2,300 horsepower, the normal speeds being 21 miles and 42 miles per hour. The draw-bar pull at 42 miles per hour ranged from 7,700 pounds normal to 20,000 pounds maximum, and from 13,500 pounds normal to 31,000 pounds maximum at 21 miles per hour.

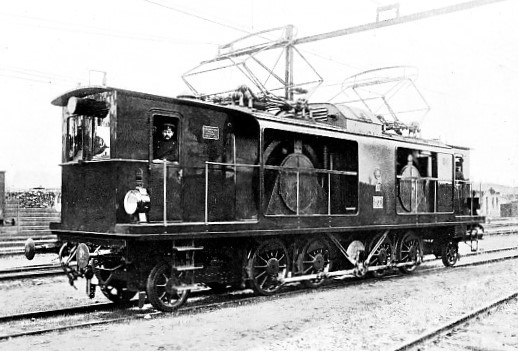

THE 1,800 HORSE-POWER 2-6-2 SIEMENS ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE, hauling a 7-car train on the Dessau-Bitterfeld Railway.

In deciding the installation it was stipulated that the speed of acceleration, when starting on the higher speed with a train weighing 300 tons, should be 0·5 feet per second, per second, for which a draw-bar pull of 16,000 pounds had to be exerted, while, when starting with a goods train weighing 400 tons at the lower speed, the rate of acceleration was to be 0·36 feet per second, per second, a draw-bar pull of 20,000 pounds being necessary in this instance.

For a time steam trains were run side by side with the electric trains in order to obtain conclusive comparative data, but it was not long before the electric traction asserted its undoubted supremacy in such a manner as to induce the abandonment of steam traction. Ultimately the installation was accepted and taken over by the Government. At the same time the possibilities of electric traction for main line working became emphasised so strongly that the Swiss Government forthwith turned its attention to the question of electrifying the whole of the lines embraced in the Federal system, which work is being accomplished slowly but surely.

Since the electrification of the Simplon Railway many powerful electric locomotives have been designed, and many important main-line electrification schemes have been taken in hand. This is particularly the case in Sweden, where elaborate experiments were continued over a period of many years in order to thresh out the issue in all its bearings. It has now been decided to electrify the main line of the State system between Kiruna and Riksgransen. An enormous mineral traffic flows over this highway to Ofoten, the great ore-shipping point on the Norwegian coast in the Arctic circle, since this line traverses the heart of the Swedish ore mining territory, connecting it both with the Baltic at Stockholm and the Atlantic seaboard.

Fifteen powerful locomotives have been built by Messrs. Siemens, Limited, for the electrified section of this railway, which is 93·75 miles in length. The locomotives are of two types, one having a four-wheeled bogie at each end and two driving axles — 4-4-4 type — and the other comprising an articulated system with two sets each having three pairs of coupled axles — 0-6-6-0 type. The horse-power in each instance, however, is identical, 1,250, while current is supplied to the contact line at a pressure of 15,000 volts with a frequency of 15 cycles per second. This company also has built some powerful machines for the 22 miles of the electrified Dessau-Bitterfeld section of the Prussian State system. The most powerful are the 2-6-2 of 1,800 horsepower, the 4-4-2 type of 1,100 horse-power, and one of the 2-8-2 class with an output of 1,250 horse-power.

But the largest and most powerful electric locomotives at present in service in Europe are the interesting machines which have been The supplied to work the Lotschberg Railway between Spiez and Brigue, a distance of 48·48 miles, including the tunnel. When this huge undertaking was sanctioned by the Federal Government it was decided to work the tunnel from its inauguration by electric traction, the experience with the Simplon tunnel line having emphasised the advantages of electricity over steam, as already mentioned.

In the case of the Lotschberg Railway, however, the conditions which had to be fulfilled were of a far more exacting character. In order that there should be no uncertainty or delay in working the tunnel directly it was opened for traffic the first section of the line, that from Spiez to Frutigen, 7⅘ miles, which was completed in 1901, was selected as a testing ground on which the two systems might be run side by side for comparative results, and also to afford some definite data concerning the best system and type of electric locomotive adapted to the heavy conditions which were to be satisfied. This section of the line was suited to the investigations, although the maximum gradient is only 1 in 65, whereas between Frutigen and Kandersteg, the northern portal of the Lotschberg tunnel, the heaviest rise is 1 in 35. For nine years the railway was steam operated, but then it was converted to electric traction on the single-phase alternating current system, the pressure on the contact line being 15,000 volts at 15 cycles per second.

THE OLD AND THE NEW ON THE SIMPLON RAILWAY. Each locomotive develops approximately the same horse-power, but whereas the 4-6-0 steam engine weighs about 110 tons, the electric unit weighs only 62 tons.

As the business over this high road was certain to equal that passing through the Simplon tunnel, and as heavy trunk railway working was to be expected, the traffic conditions of the St. Gotthard were taken as a basis in determining the electrification of the Lotschberg Railway. The Government

laid down the specifications which were to be fulfilled, and these certainly were of no light order. On the St. Gotthard line, where double-heading is practised with the heaviest trains, a load representing 310 tons, exclusive of engines, can be hauled at 22 miles an hour over a maximum grade of 1 in 37. This speed, at least, was to be equalled in electric working, although double-heading was not to be adopted. Accordingly the Government called for the most powerful locomotives that could be designed in accordance with existing knowledge of electric traction. Two locomotives were offered, one made by a Swiss company, the Oerlikon Electrical Company of Zurich, and the other by the A.E.G. (General Electric Company) of Berlin.

It was a piquant situation. Each firm has achieved a high reputation in European electrical manufacturing circles, and each was determined to eclipse the other. Accordingly two electric giants were produced, and for two or three years were run neck and neck up and down the track between Spiez and Frutigen, hauling all kinds, lengths, and weights of trains. Careful records were kept of the performances. Neither company spared any effort to show what it could do; the products of German and Swiss industry were pitted against one another.

At the time the two firms were requested to furnish the most powerful machines they could devise no single-phase locomotive exceeding 1,000 horse-power was in operation in any part of the world. This meant that considerable pioneering had to be accomplished in the design and construction of the machines. Still, the resources of each firm were equal to the task. Each supplied huge magnificent-looking machines, unmistakably bearing the imprint of possessing great haulage power. At the same time each company was under a certain restriction which precluded the possibility of carrying the power factor to an extreme degree. According to the international agreement the maximum draw-bar permitted is 22,000 pounds.

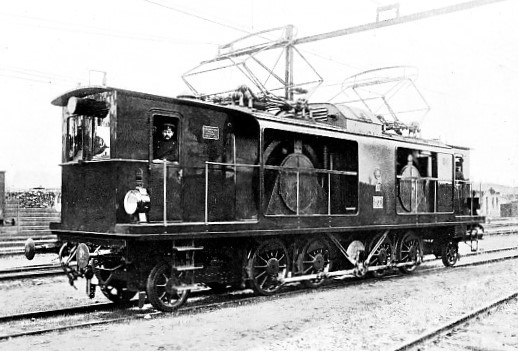

THE MOST POWERFUL ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE IN EUROPE. The 2,000 horse-power 0-12-0 electric locomotive built by the Oerlikon Electrical Company for the Lotschberg Railway.

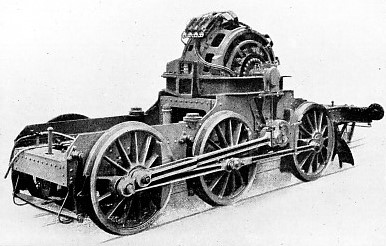

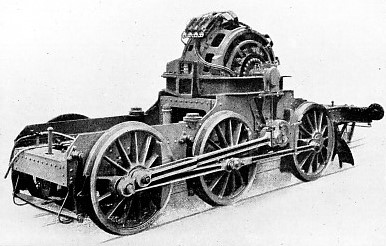

So far as horse-power is concerned the Swiss company produced the most powerful electric locomotive. Indeed, this engine, No. 121, is the most powerful alternating current electric locomotive in Europe at present, and certainly exceeds in this respect any steam locomotive working upon Continental railways. It is of the 0-6-6-0 type, having 12 driving wheels disposed in two groups, each bogie being a complete unit. By this arrangement the whole of the weight of the locomotive — 90 tons — is available for adhesion, representing 15 tons per axle. The three pairs of driving wheels of each bogie are coupled, and as the two units are housed in one cab they can be used together. At each end of the locomotive is the driver’s station together with control, so that the engine may be driven from either end, the central space being occupied by the transformers and the other electrical accessories. Each motor weighs 9·8 tons, and each transformer 5·5 tons, the total weight of the electrical equipment being 44 tons — practically one-half the weight of the locomotive. The driving wheels have a diameter of 54 inches.

Each motor develops 1,000 horse-power, representing 2,000 horse-power for the complete locomotive, at a speed of 26 miles per hour, at which speed a draw-bar pull of 22,000 pounds is exerted—the maximum permitted by the international agreement. This means that the locomotive can haul a train weighing 500 tons, exclusive of the engine, over a grade of 1 in 66, or a train of 310 tons, exclusive of the engine, up a bank of 1 in 37 at a speed of 26 miles per hour. In order to gain some impression of the significance of this haulage power it may be mentioned that to haul a train of 310 tons over a similar grade on the St. Gotthard Railway at 22 miles an hour — four miles per hour less — requires two locomotives. The combined weight of the latter is approximately 230 tons, or more than 2½ times the weight of the 2,000 horse-power electric locomotive.

The locomotive supplied by the General Electric Company develops 400 horse-power less. It is of the articulated 2-4-4-2 type, there being two sections coupled together. Each carries a motor having an output of 800 horse-power, making 1,600 horse-power for the complete engine, at 25 miles per hour. This enables the locomotive to haul a train weighing 400 tons, exclusive of engine, up a gradient of 1 in 66, or a load of 250 tons, also exclusive of engine, over a gradient of 1 in 37, at 26 miles per hour.

It will thus be seen that the Swiss locomotive with its 400 extra horse-power has the advantage in hauling capacity of 100 tons on the easier, and of 60 tons on the steeper gradient. Taken on the whole it will be admitted that the Swiss manufacturers have acquitted themselves magnificently in what was a difficult undertaking.

As a result of the trials the Oerlikon Company was awarded the contract for 10 locomotives of a similar type. Each engine will be fitted with two 1,250 brake horsepower motors, and be capablc of attaining speeds ranging from 31¼ to 47 miles per hour.

ONE OF THE SIX-WHEELED BOGIES AND ITS 1,000 HORSE-POWER MOTOR of the Oerlikon Electric locomotive built for the Lotschberg Railway.

You can read more on “Electric Giants of America and Canada”, “Electric Locomotive Classification - 1” and “Steam v. Electricity” on this website.