© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The Fastest Trains in Europe

Fast Rail Travel Across Europe

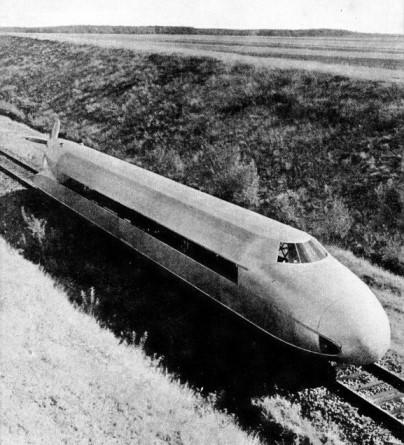

ZEPPELIN RAIL-

THE extraordinary vehicle illustrated here, half airship and half rail-

The Kruckenburg car, as it was named, appeared in 1931, and was of German design and construction. On test, it reached a speed of one hundred and forty-

The Germans have always had a flair for producing something more startling than has been seen before, and this rail-

The Kruckenburg car progressed by means of the stream of air directed rearwards by the propeller, in the same manner as an aeroplane. What would have happened if it had appeared in regular service, causing a minor hurricane on leaving a platform, is impossible to say.

The previous record of a hundred and thirty miles an hour had been gained by an electrically driven locomotive, in the year 1903. This was in the days of hansom cabs and “horseless carriages”, before the first “flying machine” had succeeded in leaving the ground. What is more, the car that travelled at such a speed, unheard of at the time, was streamlined and capable of seating fifty passengers.

A still earlier electric car had reached a hundred miles an hour in 1901, but it did so much damage to the track that the test had to be abandoned.

Before high speeds can be attempted, the track must be suitable, which is why, in spite of the great speeds possible today, speeds on many sections of line are still comparatively moderate.

A track can be unsuitable for various reasons. There may be sharp curves in it, or it may be laid over bridges on which there are speed restrictions, or speed restrictions may be in force owing to level crossings and so on. So it is sometimes not much good building a powerful locomotive without practically rebuilding the track, which is what happened in Germany and other European countries just before the Second World War.

High record speeds, however, must not be confused with high average timings. The average timing is the time taken by a train between any two points given as miles an hour, and including all stops. To gain, say, an average timing of eighty miles an hour, the locomotive must be capable of far higher speeds intermediately. The line must be cleared for it, and any slight delay may mean travelling at a much higher speed between stops to maintain the average timing.

Speed must be judged in conjunction with the weight carried. Rail speeds seem low beside those of the aeroplane and the racing car, but the weight of the average train is out of all proportion to the weight of cars and aeroplanes. Some modern passenger expresses, travelling at a hundred miles an hour, weigh as much as a thousand tons. Even freight trains in some parts of the world travel at over sixty miles an hour, and the weight of one of them may be as much as five thousand tons.

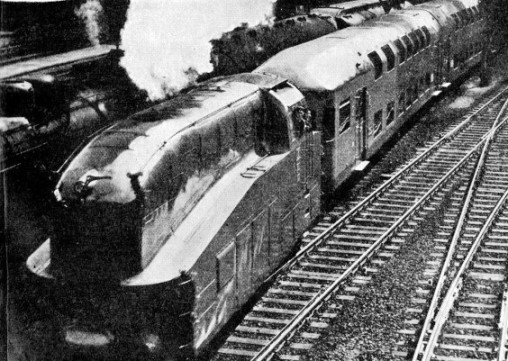

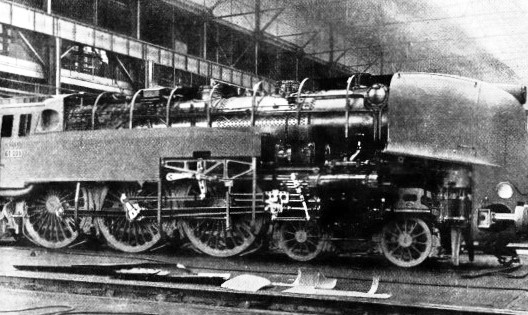

GERMAN STREAMLINED STEAM LOCOMOTIVE. Design which looks rather strange to British eyes. The streamlined covering is carried down almost to the rails, and trouble has even been taken to bend the lower sections into a reverse curve, something like the bilge of a ship. Inspection covers are provided in the bottom part of the covering in order to facilitate attention to the cylinders and valve gear.

For all practical purposes, therefore, the fastest trains are those with the highest average timings, and it was Germany that had the bulk of them. Building upon the knowledge they had gained with these early experiments, the German State Railways in 1932 startled railway circles by announcing a new service on the Berlin-

The highest British average timing then was that of the “Cheltenham Flyer”, which did the daily trip between Swindon and Paddington at seventy-

The German announcement, therefore, seemed surprising, considering the fifty-

First Diesel-

The secret lay in the high sustained speed possible with the Diesel-

The “Flying Hamburger” consisted of two streamlined coaches carried on three four-

For safety at high speeds, the cars were equipped with a double system of braking. They had the quick-

Carrying over a hundred passengers in comfort, and whirling them to their destination at a speed never known before in rail travel, the “Flying Hamburger” was an instant success. Even a refreshment buffet was provided, and the cars were connected by a gangway running their whole length, with three-

Most of the tracks over which they operated had to be rebuilt, some of them right from the foundations. The cant of the tracks on curves was increased to permit of hundred-

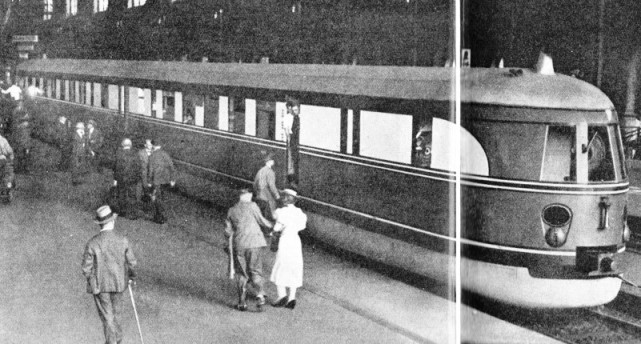

THE “FLYING FRANKFURTER”. Before the Second Word War, the “Flying Frankfurter” was one of the fastest trains in Europe. It covered the journey between Berlin and Frankfurt-

Add to all this the fact that in no other country in the world is there such a profusion of flying and burrowing junctions, and it will be obvious why the German State Railways, at the outbreak of the Second World War, had the fastest trains in Europe. They had built up gradually the right network of tracks and the right motive power for fast timings. To electricity, which they had proved long ago to be faster than steam, they had added the oil-

Not many of their lines were electrified. Germany has ample coal resources, and the bulk of the services were still under steam. Pacific locomotives of various types were used for the principal passenger trains, some of them fully streamlined. One of these on test reached a maximum speed of a hundred and twenty-

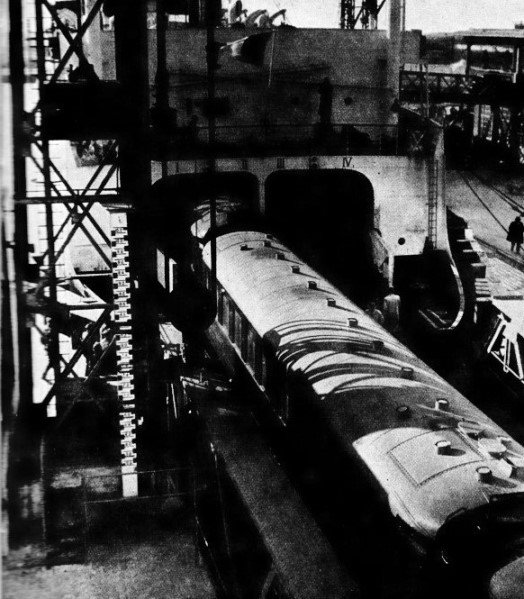

STREAMLINED DOUBLE-

Electrification, however, is the keynote of the modem Italian State Railways. Unlike Germany, Italy lacked the coal for steam, whereas she had ample water power for a hydro-

New Italian Routes

Far more than any other country, Italy has paid attention to the routes, in some cases rebuilding winding tracks entirely from one end to the other, and cutting through all obstacles regardless of cost. The new line from Rome to Naples, for example, flattens all gradients and eases curves so that unrestricted speed was permitted over the whole of its length.

Electrically hauled, the fastest Italian trains ran in three-

The engineering of some of these lines is worth considering, particularly a still later one driven through the Apennines between Bologna and Florence. Previously, the main line from Milan to Rome was carried on a serpentine course over the mountains, but the new line effected a complete transformation.

To begin with, it has cut the altitude to which the trains have to climb by half. Then it has shortened the Bologna-

The Great Apennine Tunnel on this new line ranks as one of the Railway Wonders of the World. With a length of nearly twelve miles, it is the longest in the world which has been bored sufficiently large to take a double track, and is the only tunnel which has a cross-

The signal-

The signal cabin is located in a great central hall, far below the surface, over five hundred feet long, fifty feet wide and thirty feet high. It is entered from the main tunnel at both ends, and has subsidiary tunnels extending from the ends to house the siding tracks. The tunnel is ventilated by two inclined shafts sunk originally to facilitate removal of the excavated material.

Some extraordinary difficulties had to be overcome during its construction. Poisonous gases, almost unknown in railway tunnelling, seeped into the workings and in some places caused outbreaks of fire. Another stubborn enemy the engineers had to contend with was water, which soaked in through the whole length of the tunnel. From May, 1925, to March, 1930, the quantity of water pumped out would have been sufficient to fill a lake a mile and three-

In spite of their high-

Quite a large area of the city had to be cleared to make room for it. The station buildings, horse-

The desire for greater speed and faster timings was so general before the war that it spread all over Europe, each country doing its utmost to match up with the others, and each overcoming its own peculiar difficulties in various ways. No greater contrast could be found, for example, than

that between the mountainous terrain of Italy and the flat and low-

Consequently, train runs are short in Holland, and stops are frequent, and a type of motive power was needed that would permit of rapid acceleration and a high average speed between stops. Once again both electric and Diesel-

This speed-

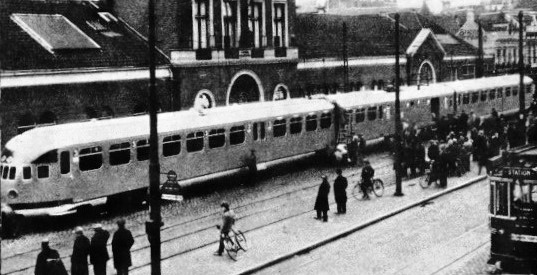

HIGH SPEED IN HOLLAND. Typical Dutch three-

Improvements in Belgium

Belgium, too, was influenced by the general railway speed-

But it is in France that the greatest strides have been made on steam lines, for it is in this country that the internal streamlining of the steam flow of the locomotive was originated. Most of the research work in this direction was done by an engineer named Andre Chapelon, who will always be remembered in connexion with the principle which bears his name. Before explaining it in detail, however, it is necessary to consider French practice in general, for French locomotive engineers have always been to the fore, and French methods have left their mark in a large way on British engineering practice.

For years the use of compound locomotives, in which the steam, after being used in a high-

The French driver is taught to make the greatest possible use of these complexities. He gets a bonus for fuel-

The indicator contains a moving tape with which the driver cannot tamper, and the tape shows the exact speed at any moment throughout the journey. This method of speed recording has since spread to Britain, but not until the first British high-

Low-

Chapelon’s whole idea was to advance economy in fuel still further, and the object he set himself was to reduce the fall in the pressure of the steam as it leaves the boiler and travels through the various cylinders. Steam retains its pressure only as long as it retains its heat; any fall in temperature means a resultant loss in pressure, and heat which has already been supplied and then lost before it can become effective is obvious waste. A further objective was to provide the exhaust steam with as free and rapid an escape through the chimney as possible, thereby reducing back-

STREAMLINED FRENCH PACIFIC. French engineers are among the finest in the world, and it is in France that some of the greatest strides have been made in steam locomotive design. It was a Frenchman, Andre Chapelon, who developed the principle of internal streamlining, whereby the flow of the steam from the boiler through the valves and cylinders to the chimney is made as smooth as possible.

The changes began with the fitting of thermic siphons, which are narrow, wedge-

A much larger superheater was also fitted, permitting the steam temperature to be increased to seven hundred and fifty degrees Fahrenheit, and poppet valves were used instead of piston valves, so improving the distribution of steam in the cylinders. Last of all, a double blast pipe and a double chimney were introduced to improve the exit of the steam.

The results were revolutionary. After some preliminary tests, the improvements were incorporated on some rebuilt “Pacific”-

Chapelon’s achievement on a rebuilt engine was astonishing. He showed by such economical working that steam was by no means an outdated power, and most countries have followed the principle of internal steam streamlining. Double blast pipes and either double or huge circular chimneys are the chief signs of steam streamlining in Great Britain.

It is curious that such a simple and effective idea should have come from a country whose engines are so complex, but it was quite possibly the reaction from complexity that produced it. This is the case with signalling, at all events, for French signalling was at one time even more complex than French locomotives. The number and variety of types of signals used in France were extraordinary.

In stop signals there were no fewer than three different kinds. There was a curious type of chessboard stop signal for main lines, a square stop signal for subsidiary lines, and a circular type of signal known as the outer deferred stop signal. Then there were diamond-

There was another simplification just before the Second World War, when all the French railways of former days were amalgamated into one national system. They are divided up into regions known as the Northern, Eastern, South-

French engineers have also shown surprising skill in the building of their railway bridges. They have some magnificent examples to their credit, but most of them, unfortunately, are hidden away in remote valleys where the average traveller is unlikely to set eyes on them. One of these, the Garabit Viaduct, was designed by Eiffel, builder of the famous Eiffel Tower in Paris, and carries the railway on a magnificent arch more than four hundred feet above the River Truyere.

FAMOUS FRENCH EXPRESS. Well-

Not far away from this, in the Puy-

The French Fades Viaduct is the highest built up by man. It has three enormous spans resting on huge, tapering granite piers, but so simple and beautifully balanced is the design that the height of the bridge, at first sight, passes almost unnoticed.

Another spectacular and ingenious bridge is the Viaur Viaduct over the Viaur River. This boasts the biggest span in France, one of seven hundred and twenty-

Electrification in France

There are two main electric lines in France, from Paris and Orleans to points on the Spanish frontier. Direct current of fifteen hundred volts and overhead conductors are used, the supply being obtained from hydro-

The suburban traffic at some of the Paris terminal stations is enormous. St. Lazare, for example, handles over a quarter of a million passengers every day. Even the Gare de l’Est handles daily between seventy and eighty thousand.

The traffic at these two stations, in fact, has risen to such dimensions that it has been quite impossible to handle it all in ordinary coaches. The French have, therefore, provided double-

Paris is more than a capital with its own heavy traffic, however; it can rightly be called the terminus for the whole of Europe. Every day, before the war, there started from Paris some of the most famous luxury expresses in the world, carrying passengers all over the continent to the fringe of the Orient. These were the trains-

They were available to both first and second class passengers, and the traveller could book from Paris to cities as far distant as Athens or Istanbul. What is more, he could travel to his destination in the same coach. The running of such through trains all over Europe was a most complicated business, with steam haulage in some places and electric haulage in others, not to mention the crossing of frontiers and customs barriers; but European standard gauge made it possible mechanically, and all the other difficulties were more than anything a question of international agreement and organization.

STREAMLINED COVERING of steam locomotive partly removed to show boiler. The engine is of German construction, and is a high-

Some of the cars of the Company are ingeniously arranged. The first-

In this way the accommodation of the train can be varied quite easily, according to whether the greatest demand is for first or second-

Everybody has heard of the famous “Blue Train” to the Riviera. It earned its name not so long ago simply because it was one of the first to be changed from the original varnished teak to a livery of dark blue. Officially, it was known as the Calais-

They followed the same route as the “Blue Train” as far as Dijon, but here the “Rome Express” branched off to Culoz and Modane, where the Italian State Railways took charge of it, while the “Simplon-

The “Simplon-

Besides the “Simplon-

It will be appreciated that the staffs of such trains must have a good knowledge both of languages and of money exchange rates. As each frontier is crossed, all the menu cards in the restaurant cars have to be changed, and bills made out in accordance with the currency of the country. This means keeping small change in the coinage of every country through which the train passes, for few passengers think to provide themselves with all the variety of coinages they may need on a journey such as this.

AUTO RAIL-

Another and more serious difficulty is that every coach must be fitted to conform to the safety requirements of every country through which it passes. Further, it must have couplings suited to the many different types of locomotive that are used. Quite a lot has been done to standardize such fittings, but it is still necessary to fit these international trains with several different kinds of brake and other equipment.

Coaches fitted for steam-

Britain seemed to be isolated from this long-

Dover-

The passage across the Channel was accomplished by means of the Dover-

At Dunkerque the reverse procedure takes place. The cars are transferred by a shunting locomotive from ship to shore, and there attached to an express for Paris. And from Paris, of course, they take their place in any of the luxury trains as desired.

At Dunkerque the reverse procedure takes place. The cars are transferred by a shunting locomotive from ship to shore, and there attached to an express for Paris. And from Paris, of course, they take their place in any of the luxury trains as desired.

CROSS-

Apart from the main-

The great increase in road transport, however, sounded the death-

The petrol engine was installed in rail-

These petrol cars are different from the Diesel-

Spanish Railways

The railways of Spain and Portugal can hardly be compared with those of the rest of Europe. To begin with, they are laid down to the much wider gauge of five feet six inches, which prevents any through running of coaches from the standard gauge, and more or less cuts the two countries off from the general progress. All traffic for Spain has to be unloaded and reloaded at the frontier stations in the Pyrenees, a slow and costly business. In addition, the interior of Spain is very mountainous, and no speeds of any note are performed even on the main-

It is noteworthy, however, that Spain, like all the other countries of Europe, has amalgamated the larger private railway companies into one national system, in an attempt to bring them up to date. The change-

Past and present rub shoulders in Spain in a curious way. On the main lines, although high speeds are not obtainable, an express train may be hauled by a powerful locomotive of modern wheel arrangement suitable for heavy grades, with rolling stock including saloon coaches of the Pullman type. But a journey over a country branch in a mixed passenger and goods train is a very different experience.

Nevertheless, Spanish railways can show some fine engineering feats, chiefly in the Pyrenees Mountains, where the French and Spanish lines connect. There are some tunnels which had to be bored out of solid rock, one over three miles in length, and another in a spiral curve for the purpose of surmounting a sudden change in level. In addition, there are several viaducts, one, the Gisclard, designed on the lines of a suspension bridge, with a central span of over five hundred feet carrying the rails two hundred and sixty-

There are some excellent stations, too, in the larger Spanish cities, chiefly in Madrid and Barcelona. Barcelona also has a cable or suspension railway over the harbour, and Madrid has an underground system of the high-

There are some excellent stations, too, in the larger Spanish cities, chiefly in Madrid and Barcelona. Barcelona also has a cable or suspension railway over the harbour, and Madrid has an underground system of the high-

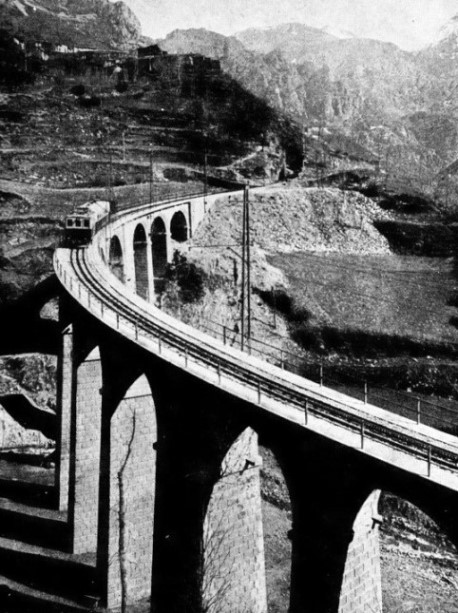

ELECTRICITY IN THE PYRENEES. Most Spanish railways are steam-

You can read more on “Belgium’s Steel Network”, “The Rome-