Across Europe from London to Istambul

FAMOUS TRAINS - 6

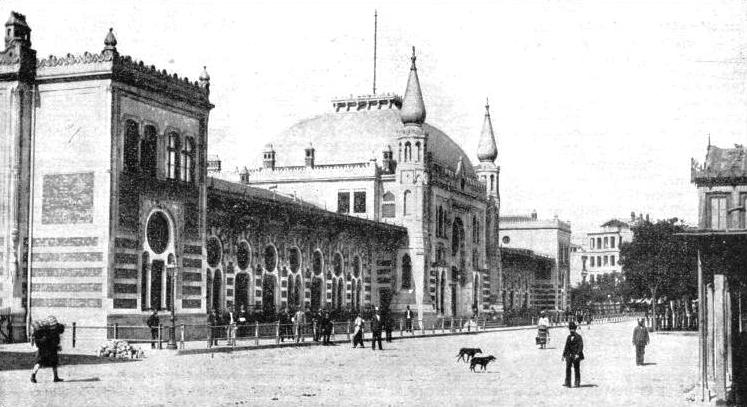

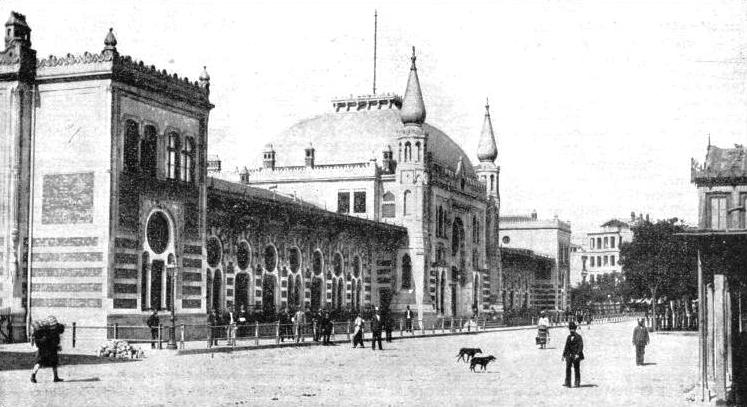

THE SPELL OF THE ORIENT. The Sirkedji railway station at Istambul, where the “Orient Express” reaches the end of its journey. Istambul was formerly known as Constantinople.

THE “Orient Express,” connecting as it does the English Channel with the Black Sea, is one of the most famous trains in Europe. An American friend of the writer, after having considered the claims of the “Flying Scotsman” and the “Twentieth Century Limited”, admitted that the “Orient Express” might claim to be the most famous train in the world. With its connecting trains it passes over the railway systems of no fewer than thirteen different countries of the continent of Europe.

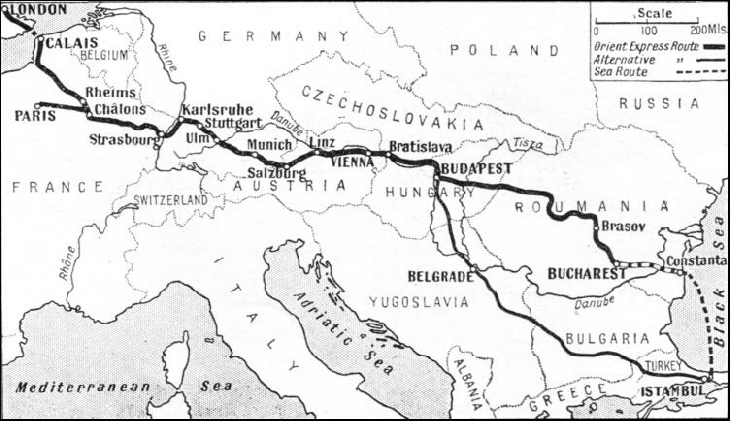

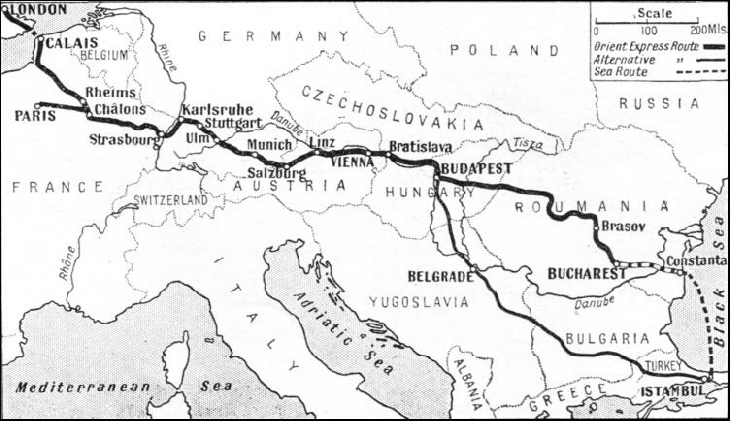

The “Orient Express” proper runs from Calais and Paris to Bucharest, passing through France, Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Romania. Then there is the closely-associated “Simplon-Orient Express,” which takes its way farther south, through Switzerland, Italy and Yugoslavia. From Nish, in Yugoslavia, there is a connexion for Athens, while the main part goes on through Bulgaria to Istambul (formerly known as Constantinople) in Turkey. Finally, returning to the north, the “Ostend-Vienna Express” connects with the “Orient Express” at the latter city, providing a through link with North Germany and Belgium. The “Orient Express” links up with the “Simplon-Orient Express” by a connexion between Budapest and Belgrade. Such, in outline, are the ramifications of the “Orient Express” and its associated services.

THE ROUTE OF THE EXPRESS and the towns through which it passes are clearly seen in the map.

Of all the International trains of Europe - and of the world for that matter - the “Orient Express” is the most international. Thirteen countries make a good total. The “Orient” is also the oldest-established of Europe’s transcontinental’s, for it was the first to be composed entirely of rolling-stock belonging to the International Sleeping Car Company. It began running between Paris and Vienna in 1883, barely a decade after sleeping-cars were first known in Europe. The cars of that date were six-wheelers, with four-berth compartments, and lighting was by means of old-fashioned German petroleum lamps. Travel in them, however, was by no means uncomfortable, for the berths were good enough once one had gone to bed, and by reason of their considerable weight (for those days) the cars ran fairly easily in spite of their rigid wheel-bases.

The locomotives were of the 2-4-0 type, usually with double frames, while the Austrian examples burnt brown coal, and had huge, basin-shaped tops to their chimneys. It must have been a jovial, but not very speedy-looking train. But in its fifty-two years of life the “Orient” has become a household word on the Continent, especially in Central Europe.

Before the Great War, the services provided by the “Orient” had attained something of their present ubiquity. Three times weekly the train left the Gare de l’Est in Paris for Constantinople, as it was then called. At Linz the train joined the route of the “Ostend-Vienna Express”, following this to the Austrian capital. At Budapest, the Berlin-Constantinople sleeping-car was attached, then the train ran down to Turkey through Belgrade and Sofia. The war, needless to say, stopped the “Orient”. Two battle fronts crossed its route; the Eastern Railway of France, on which its journey from Paris began, was cut in two by the Western Front. Beyond Vienna was the turmoil of fighting between Austria-Hungary and Russia, and between the armies of Serbia and Bulgaria and Turkey. Yet the cause of the suspension of the “Orient Express” was also that of the enlargement of the service after the war.

The “Simplon-Orient Express”

While feeling still ran strong even when peace came, the International Sleeping Car Company began a service which connected London, Calais and Paris with the Near East without passing through Germany, or any part of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. The new train was called the “Simplon-Orient Express”, and as such it remains to this day. Instead of going straight across Central Europe, like the old “Orient,” the younger train runs through Switzerland, down into Italy through the Simplon Tunnel. It crosses the northern plains of Italy, passing through Milan, Verona and Venice to Trieste. Thereafter, northern Yugoslavia is crossed, calls being made at Laibach, Agram and Brod. Finally, at Belgrade, the route of the old “Orient Express” is rejoined, and the through connexion with the present “Orient Express” is picked up.

In the nineteen-twenties it was realized that this diversion of the through train from Calais and Paris to Constantinople left a gap in the Continent’s through communications. The “Orient” began once again to run through South Germany and Austria, only now its real destination was not Turkey but Romania. The long and the short of it was that the service provided was twice as good as the old one.

A journey by the “Orient Express” to-day is, to a dull person, merely a means of getting across Europe. To those with imagination - in which class one may place the majority of railway enthusiasts - it is a source of fascinating instruction. Now and then one hears people talking about the “tedium” of a long railway journey. There is no tedium on a long railway journey, least of all on one which takes you through the most important countries in Europe. Was it not Robert Louis Stevenson who held that to travel was more important than to arrive?

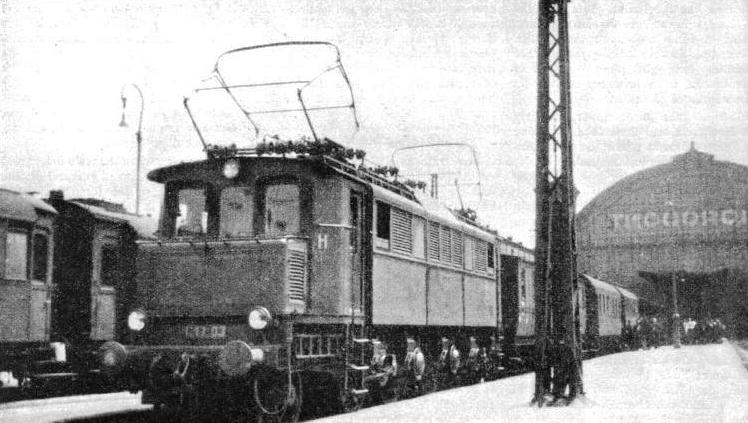

LEAVING VIENNA FOR PARIS. The “Orient Express” covers the stretch, of 117½ miles between Vienna and Linz, in two hours fifty-five minutes.

The “Orient” journeys from the broad fields of Normandy, with rolling downs and huge plough horses - all rather like Kent or Sussex - through the colourful Danubian basin, to the half-squalid, half-magnificent cities of the Near East. Along its route dwell Normans, Latins, Teutons, Slavs, Magyars, Gipsies, Turks, and in Romania, Latins again. One can contrast the fine modern railway systems and rolling-stock of France and Germany with very different things in the Balkans. One can look out of the beautifully appointed sleeping compartment, late in the evening, into the bare wooden compartment of some unfamiliar local train, where half-Eastern looking peasants are smoking long gilt pipes over queer bundles of farm produce, stacked in the middle of the floor.

Let us take an imaginary journey to Bucharest and Constanta, retracing our steps, too, to follow the connexion through Belgrade to Istambul.

To catch the “Orient Express” from Calais, we take, on a Tuesday, Thursday, or Saturday, the 2.0pm “Continental Express” from Victoria to Dover. Our first view of the famous train at the Calais Maritime station is, perhaps, disappointing, for all we see is a large blue sleeping-car attached to a relatively ordinary French express train, the latter headed by one of the big, brown compound locomotives of the Northern Railway of France. The main part of the train is still in the carriage sidings at Paris, and will not leave the Gare de l’Est until two and a half hours after the through coach leaves Calais punctually at 5.25.

Through northern France, the train crosses some of the most fought-over country in Europe, though it looks smiling enough in the gathering dusk.

During the past hundred years, it has seen the Franco-Prussian War and the Great War, though but for place names which are familiar to some of us, one would never know it. Rheims, in the evening dusk, looks as peaceful as ever, though it was nearly shelled to pieces barely twenty years ago. On the plains of Chalons, over which the train runs late in the evening, the advance of Attila the Hun, with his Asiatic hordes, was finally stemmed centuries ago.

Crossing the Frontier

The train is little disturbed when, eventually, it draws up at Chalons, and the through coach from Calais is attached to the main section from Paris. The “Orient” carries no local passengers, and now in its complete form consists of sleeping-cars, a restaurant car, and two bogie vans, all belonging to the International Sleeping Car Company, and painted their standard royal blue colour.

The train has an opulent air; the cars travel with little vibration, the equipment is extraordinarily comfortable and clean, and so smooth is the running that it is difficult to realize that in comparatively recent years the French permanent way was not all that it should have been.

The beds are made up, and the majority of the passengers are either retiring or already in bed when the train slips off into the night behind one of the big locomotives of the Eastern Railway of France. It may be one of the huge 4-8-2 “Mountain” engines, but as the “Orient Express” is light compared with the immensely long ordinary express trains for which these locomotives have been designed, it is more likely to be one of the 4-6-2 type. The conductor of our car has taken care of our passports and tickets, so we shall not be disturbed in the night, even though we cross the Franco-German frontier in the small hours of the morning.

All is quiet when the train draws up at Strasbourg at 1.53am, and nothing can be seen of the famous cathedral with the tall spire and the queer stump of the second spire that was never built. Only the massive locomotives and green coaches in the station outside the windows are there to remind us that we are in Alsace-Lorraine. Perhaps, too, someone on the platform can be heard speaking in a peculiar jargon of French and German, though there are few people about at this hour.

Alsace-Lorraine has had its own railway administration under both German and French rule, and it is behind one of their locomotives that the train glides out of the station after a wait of six minutes, and hurries away to the East. We have made our last contact with France, and the train thunders through the frontier station at Appenweier, nor does it pause in its stride until it has penetrated Germany for a considerable distance. At 4.32am, it draws up in the Main Station of Karlsruhe. The time is changed now from that of Greenwich to that of Central Europe, and when we put things to rights at breakfast time, we shall have to advance our watches by one hour.

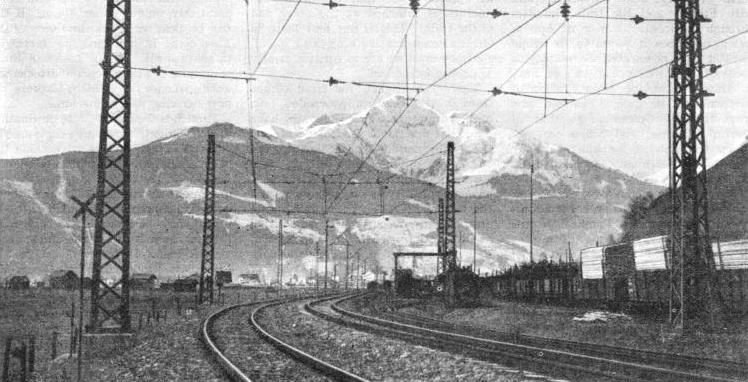

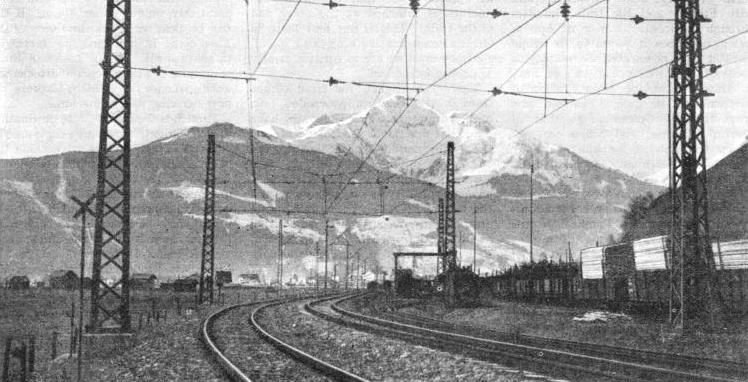

ON THE TRACK OF THE “ORIENT EXPRESS”. A stretch of line over which the famous train passes, at Zell am See in the Austrian Alps.

The German locomotive which now backs on to the train is probably a four-cylinder compound “Pacific” of the type formerly standardized by the Baden State Railway, and a number of which have appeared, in an improved form, under the present German State Railway Company. She is a long, lean-looking engine, with a very high running plate, a pointed front, and the sand-box on the top of the boiler under the same casing as the dome.

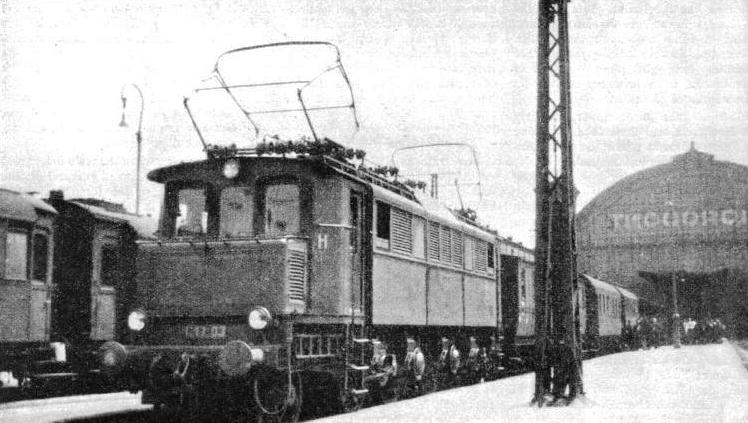

Probably we are still abed when the big-wheeled locomotive brings us into Stuttgart, the capital of Württemberg, at six minutes past six in the morning. To those, however, who are awake, an interesting process takes place. Stuttgart Main Station is a terminus, and while the “Pacific” is uncoupled from the train, a big twelve-wheeled electric locomotive, taking alternating current at 15,000 volts from overhead conductors, is attached at the other end of the train. This is our first taste of electric main-line working, and it will continue until we are in Austria, nearly 244 miles farther on.

East of Stuttgart, the train climbs through the beautifully wooded hills of the Jura range. Those of us who have read that fine novel Jew Suss will find the hill country of Württemberg strangely familiar and un-foreign. It is a beautiful country in the early summer, when the fruit trees are in blossom and the woods still retain their vivid spring green. Until recently, the negotiation of this section used to be accompanied by much laboured puffing, which - with heavy trains containing three classes of coach - came from behind as well as in front.

First View of the Alps

Now the big electric glides up the incline almost silently, and when she reaches the down grade beyond the summit, she glides down it in the same imperturbable fashion. The old steam engines used to sprint down as if they were frantically making up for the previous up-hill crawl.

Ulm, with its tall, decorated cathedral, is reached during breakfast, but the train steams through and crosses the muddy Danube into Bavaria. Thence to Munich the country is flat and comparatively uninteresting, though if the day be clear we get our first view of the Alps, lying in a jagged line tar away to southwards. In the flanks of those mountains lies the Kochel hydro-electric works, whence the “Orient Express” is now deriving its driving force.

Munich is the first definite destination of the “Orient”, for many people use the train as a rapid means of reaching the beautiful Central European capital overnight. There is something friendly yet unfamiliar about Munich, and its huge cathedral church, of red brick, with bright green domes surmounting the towers.

Here, again, is a terminus, and another electric backs on to the “tail” of the train. On leaving, the train boxes the compass, for it makes a one-third circuit of the city, at the beginning of which it is heading back westwards, and at the end of which, after crossing the River Isar, and as it passes through the Munich East Station, it is running due east. It now climbs, barely perceptibly at first, though it is already over a thousand feet above sea-level. After Rosenheim has flashed by, the climbing is in real earnest, and the high, snow-slashed mountains dividing Germany from the Tirol are a continuous delight all the way to the Austrian frontier. This is, in some ways, the most beautiful of all the Alpine regions. Schubert and Elgar both found inspiration for their music in the Bavarian Alps.

FROM STUTTGART TO SALZBURG, the “Orient Express” is hauled by a German State Railway electric locomotive of the type shown above.

The frontier is crossed just beyond Freilassing, but Salzburg is only a few miles farther on, and here our big electric comes to a halt at 11.06am. But there is no time to get out and look at the surrounding mountains, or the fairy-tale castle on its great rock. The train waits while the Austrian Customs officials and frontier police examine it and the passengers. Mean-while, the electric locomotive has been detached from the head of the train, and an Austrian steam locomotive, either a

2-6-4 with a taper boiler or a 4-8-0 has taken her place.

Austrian steam locomotives are peculiar to British eyes. Many of them burn soft brown coal, and as we glide out into the open, we shall probably see a station shunting engine sporting an enormous spark-resisting chimney, shaped like a gigantic mushroom. The electrified line to the Arlberg route and to the south can be seen veering away to the right from a triangular junction as we steam away into Upper Austria.

At Linz, which is reached at lunch time, the “Ostend-Vienna Express” arrives shortly after the “Orient”. It includes a through sleeping-car for Budapest, and hereafter, leaving at 1.25pm, the two trains are run into Vienna as one, possibly behind a very large 2-8-4 locomotive of recent construction. Vienna (West) is reached at 4.25, one intermediate stop having been made at St. Pölten. Vienna is not quite the end of the West, and not quite the beginning of the Near East, yet it is a definite fact that holiday-makers feel a suggestion of the “Eastern atmosphere” in Vienna; and this is sufficiently strong to make them go exploring farther, into the Balkans or down to the Black Sea. For them the “Orient Express” is ready. This Eastern suggestion began to creep into the scenery, though not into the people, right back in Bavaria. Possibly the bulb-topped church towers are responsible for it in the beginning.

Nearing the East

After Vienna comes a slightly bewildering series of frontier crossings, for, instead of running straight across the border into Hungary, the “Orient” makes a detour in order to call at Bratislava, in Czechoslovakia. The train waits but thirteen minutes at Vienna; less than two hours later it is at Bratislava. At 9.35pm it has reached the beautiful Hungarian capital of Budapest, behind a Hungarian 4-8-0 locomotive of formidable appearance. The Danube, in and out of the valley of which we have been slipping all day, is a much greater river now than the brawling, coffee-coloured stream which probably disappointed us away back at Ulm. Budapest, or rather, the twin cities of Buda and Pesth, have a definite smack of the Near East about them, though the architecture is still Western. The unfamiliar Magyar tongue, utterly unlike German or French, sounds decidedly exotic if one has not become used to it. The garb of some of the peasants, if any happen to be about on the station, is still more exotic; it seems to be a queer mixture of Balkan and Slav in its conception. The Hungarian locomotives are strange, too, but in another way, for they are about the ugliest in Europe.

Cars are detached at Budapest, which is one of the most important railway centres in Eastern Europe. From here the connexion runs south-east to Belgrade, where it picks up with the “Simplon-Orient Express”, giving direct access by rail to Athens, Sofia and Istambul.

Athens, incidentally, was the last of the great European capitals to have through railway communication with the rest of the Continent, for the wonderful scenic line of the Hellenic State Railways down through the Balkans is of post-war construction.

At five past ten, the “Orient” rumbles out of Budapest into the night on the last big lap of its journey, and, incidentally, the slowest. In Romania, we have none of the fine non-stop running between city and city which we enjoyed in France and Germany. Arad, the first Romanian town, is reached at the inhospitable hour of 3.48am. A Romanian engine heads the train, and if we are awake we can hear, outside, the strangely Italian sound of Romanian speech, a legacy of the ancient Roman Empire. Both Italian and Romanian are about equally derived from Latin.

AT STUTTGART. The principal railway station of this important South German city, which is a stopping-place for the “Orient Express.”

Going forward from Arad the train follows the valley of the Maros for a considerable distance. Copsa Mica is reached at 8.30am. Eastern Europe time, the clocks having been advanced by another hour. Now we climb up into the Transylvanian Alps, reaching the walled mountain town of Brasov at 11.22. The glorious beech woods of Transylvania take us back to the west, but Brasov does not, nor do the buffaloes in the fields, which are bred for work and for milk, just as they are in India.

Hereafter comes a down-hill run, and after making calls at Predeal, Sinaja, and Ploesti, the “Orient” rolls into Bucharest at 2.55 in the afternoon. For all its Latinity, Bucharest looks like the East, and, by most accounts, smells like the East, but it lacks the brave stateliness of the Hungarian capital. The run from Calais to Bratislava has occupied the round 24 hours, while Bucharest is brought within 44 hours 30 minutes of Calais, 47 hours 55 minutes of London, and 42 hours of Paris. The Constanta connexion leaves Bucharest at 6.05pm, reaching the Black Sea port at 10.23. An easy overnight voyage down the coast brings us to Istambul at 1.0pm the next day. This may waste a good deal of time, as the “Simplon-Orient Express”, with its through connexion via Budapest and Belgrade, has arrived earlier. The Constanta steamer, moreover, is a “Saturdays only” institution. But whereas the approach to the old Turkish capital by water is one of the most beautiful in the world, that by train is decidedly depressing.

The fastest running made by the “Orient” is over the French and German railways. The run from Chalons to Nancy over the Eastern Railway, covering a distance of 111½ miles, occupies exactly two hours; from Nancy to Strasbourg, ninety-three miles, the train takes 1 hour 39 minutes; on the electric section between Stuttgart and Munich, 149¾ miles, including the long climb up the Geislingen Incline, it occupies 2 hours, 50 minutes. The remainder of the electrified section is exceedingly mountainous, especially over the Alpine foothills between Prien and Traunstein, but the ninety-five miles between Munich and Salzburg occupy 1 hour and 52 minutes only. In Austria, the speeds drop, and in Eastern Europe the march of the “Orient” is made at a sort of loping trot, dignified but uninspiring.

Such is the present-day run of Europe’s oldest and best-known transcontinental express.

Until quite recently, the “Orient Express” carried first-class passengers only, in this way resembling all the old-established trains operated by the International Sleeping Car Company. In Victorian days, whether on the Continent or in Great Britain, sleeping-cars for any but first-class passengers were unheard-of, and the International Sleeping Car Company, especially where its crack trains were concerned, stuck to the old tradition as far as it could. But in recent years, Continental travellers have come, more and more, to look upon the second class as we look upon the first, and to treat the real first class as a sort of “fancy extra” for people who want to make sure of travelling in solitary state. The writer of this chapter once saw in Germany a second-class coach in which all the compartments were lined in green velvet except one, which had red. The guard, on being asked why, replied: “Ah, sir, - it is so that we can turn it into a first-class if anyone should want it. You see, they’d expect it to look different.” Apart from the colour of the cushions, the convertible compartment was identical with the others.

The International Sleeping Car Company has found a serious competitor in Central Europe in the form of the Mitropa Sleeping Car Company, a German firm. The Mitropa cars provide sleeping berths for all classes, and though it is slower, the Mitropa service from Flushing to South Germany began to offer a cheaper facility, but one just as comfortable as that of the “Orient Express” from Calais. As a result of this, the “Orient Express” now carries first- and second-class passengers. The compartments are all the same, but if you travel first class you have one to yourself, whereas if you have a second-class ticket, you have to share it with someone else. In spite of the democratic tendencies of the Mitropa Company on the Flushing and Hook of Holland services, however, the “Grand Old Lady” of Europe’s expresses still refrains from carrying third-class passengers.

When the train started running again after the war, the pre-war rolling-stock was used again, this having been either laid up or used for official purposes. The Armistice was signed in one of the International Company’s dining cars.

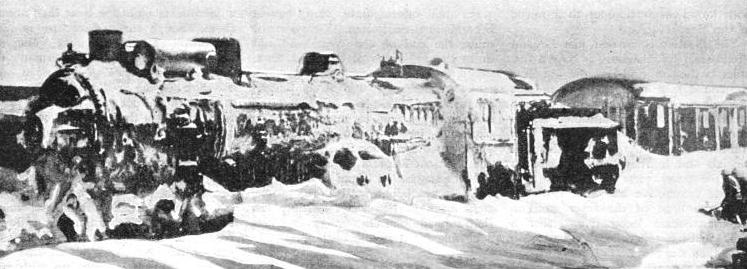

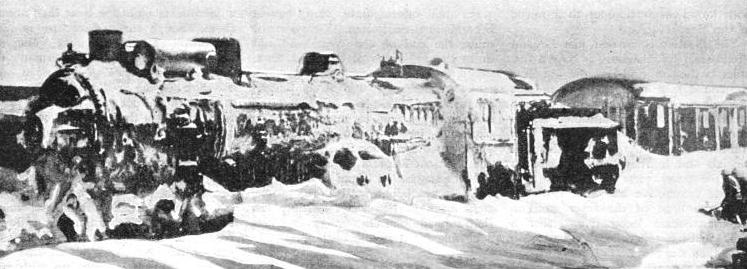

SNOWED-UP. This remarkable photograph shows the “Orient Express” imprisoned by snow, sixty-two miles from Istambul.

SNOWED-UP. This remarkable photograph shows the “Orient Express” imprisoned by snow, sixty-two miles from Istambul.

You can read more on “International Sleeping Cars”, “The Taurus Express” and

“The St Gotthard Pullman Express” on this website.

SNOWED-

SNOWED-