© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The Railway Invasion of India - 2

How the Western Ghauts were subdued by the engineer, and western and eastern India brought into railway communication

RAILWAYS OF THE COMMONWEALTH -

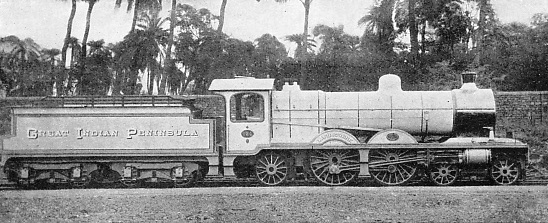

THE “LANDSDOWNE” EXPRESS LOCOMOTIVE (TYPE 4-

THE second great engineering triumph over the rampart of the Ghauts is the Bhore Ghaut incline, which bears the southeastern division towards Madras. It is 29 miles south of Kalyan by rail, and in point of magnitude is the more impressive work, measuring 15·8625 miles in length to overcome a difference of 1,831 feet in level between Karjat at the foot and Khandala at the top of the mountain wall. At this point the barrier is equally ragged; 25 tunnels with an aggregate length of 11,985 feet -

The total cost of these two inclines, aggregating 25·1875 miles, was approximately £1,067,000; of this sum, that up the Bhore Ghaut absorbed £700,000, and that of the Thull Ghaut £367,480. The average cost of the former, per mile, was the heavier; the figure reaching about £44,000, thus constituting one of the most costly pieces of trunk road mountain railway-

In the ascent of the Bhore Ghaut the engineers and contractors were harassed by many difficulties apart from those of a technical nature. Work could only be carried on for about nine months out of the twelve; it had to be almost suspended during the other three months owing to the monsoon. On the other hand, during the hot season, water was almost a priceless commodity. None was forthcoming upon the site. During the construction of the lower section it had to be drawn from Oollassa by bullock trains maintained for its transport over the intervening five miles of high road; while for the upper section it had to be moved by the selfsame means from Khandala, until pipe-

To minimize the water trouble one novel expedient was adopted. Upon the completion of one of the tunnels it was sealed at the ends to form a reservoir which became charged during the rainy season, and provided an adequate source of supply for the work in its vicinity during the following nine months.

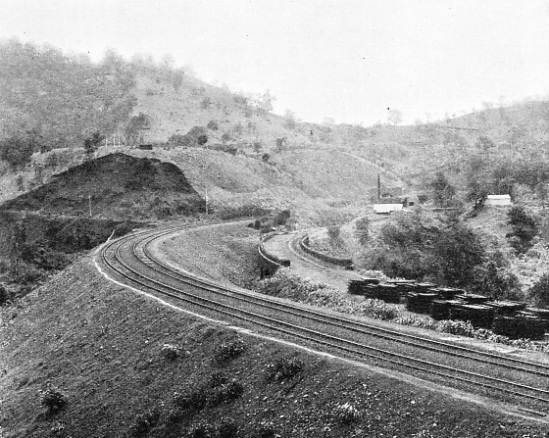

REALIGNMENT OF THE THULL GHAUT INCLINE. On the left is seen the new bank with double track, and the old track of the ‘sixties, dismantled, on the right. The task, which occupied five years, was completed in September, 1918.

Explosives were consumed upon a stupendous scale to blast the way for the steel highway up the Ghaut. Powder vanished at the rate of 2½ tons a day in cutting and tunnelling operations during the 33 months that the work was in full swing, and more than 6,000 “shots” were fired every day. At times the daily average of “shots” soared to 20,000.

Despite the steepness of the ruling grade upon the Ghauts -

This has been due, in the main, to the method of moving traffic over the inclines. Every goods train was divided to pass up or down in two sections; the trains were split and remade up at the special base and summit stations of the heavy pull. The process took up some time, while further delay was encountered at the reversing station, but, on the axiom that it is better to be safe than sorry, the practice was faithfully maintained.

The worst accident caused through a runaway train was on the Bhore Ghaut on January 26, 1869, when the descending mail train got away. The driver strove desperately to regain control, and did succeed in bringing the speed down to about 15 miles an hour when approaching the reversing station. Had there been another two or three hundred yards’ run he would doubtless have brought the runaway to a standstill, but, as he was denied this fortunate facility, part of the train went over the steep slope at the end of the reversing station, to become a wreck; 19 natives were killed or succumbed to their injuries, while 42 natives and one European, were injured. Investigation revealed the disaster to have been due to cumulative causes -

Another accident, fortunately unattended by any casualties, which also occurred on the Bhore Ghaut during 1867, was of a different and more remarkable character. The line was carried across a ravine at one point by a masonry structure having eight arches of 50-

THE GREAT INDIAN PENINSULA RAILWAY NEAR KHANDALA (BHORE GHAUT). Khandala lies at the top of the mountain wall, and Karjat at the foot. To reach the former from the latter a difference of 1,831 feet in level had to be overcome in about 16 miles. The ruling gradient is 1 in 37, and the easiest bank is 1 in 330.

A train passed over the bridge at 6.30 on the morning of July 19, but the driver apparently did not notice any untoward vibration. An hour or so later a platelayer walked on to the bridge to carry out his routine duties. He was tightening a chair key when he felt the ground sink beneath him. Helter-

Subsequent investigation revealed that the collapse was due to bad construction. Thereupon Mr. George Berkley, the “Father of the Inclines”, then consulting engineer to the company, made a personal inspection of every bridge and culvert, and certain works were set down for reconstruction; the cost of this was defrayed from a special “Casualty Fund” created by periodical contributions from revenue. This fund was maintained for such renewals until 1881, when it had attained a sum far in excess of all requirements. It was readjusted, leaving a sufficient balance to carry out all such work as might be considered necessary up to 1900.

The fearsome Ghauts successfully scaled, the engineers pushed ahead with the two roads, the main to Calcutta proceeding north-

As previously mentioned, the engineer-

He was persuaded to this decision by the existence of the two excellent high roads which had been driven over the Ghauts for military purposes; these constituted excellent channels for the dispatch of material by bullock-

On the southern section the line was pushed ahead with similar energy from Khandala at the top of the Bhore Ghaut, 44 miles from Kalyan, to Sholapur, 106 miles beyond.

Although the subjugation of the Ghauts constitutes the most spectacular achievement of railway-

The price paid for the railway victory, however, was heavy. Smallpox, cholera and other dread maladies indigenous to such pestilential country, and famine, struck down Europeans and natives alike, the death-

The going on the other two divisions, the “Central Route” to Nagpur and the southern line to Raichur, was less eventful; the first-

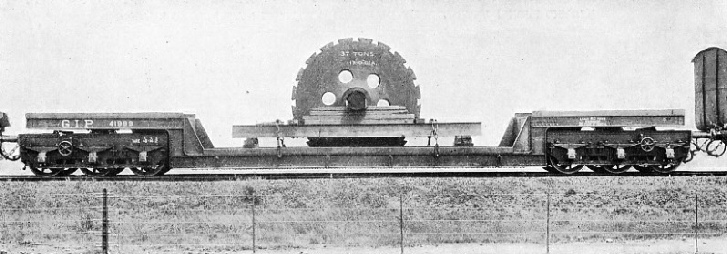

A LOADED WELL-

The opening of the 340 miles from Bhusaval to Jubbulpore was the occasion for great jubilation; H.R.H. the Duke of Edinburgh and his Excellency the Viceroy participated in the inaugural ceremonies. As a matter of fact, through communication was not possible until many months later, because the heaviest bridges and viaducts, particularly the Towa Viaduct, had not been completed.

Bridging on the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, as upon all the other trunk roads of the country, is heavy, owing to the enormous width of the waterways. The Ivistna Bridge, with its thirty-

The completion of the three steel arteries across the country gave a wonderful stimulus to railway expansion, but it was realized that the adoption of the 5 feet 6 inches gauge was somewhat prejudicial to the opening up of vast rural territories. Consequently, for “feeder” lines, a narrower gauge was authorized on the theory that such “light” railways permitted cheaper construction. The first of these roads to be opened and linked up with the Great Indian Peninsula main line at Jalamb was the Khamgaon State Railway, opened for service on March 4, 1870. Since then thousands of miles of “light ” or “feeder” lines have been laid down, ranging from 2 feet to 3 feet 3⅜ inches gauge.

So far as the Great Indian Peninsula system is concerned, the most notable railway of this character -

Bombay being the great entrepôt on the eastern seaboard of India, with enormous rivers of traffic incessantly flowing in and out, it is scarcely surprising that, in time, the carrying capacity of the steel highway, though liberally endowed, should be found to be approaching its limits. The territory served by the system is of immense area, with the innumerable “feeders”, radiating like twigs from the three main stems, springing from the trunk which extends for 34 miles from the seaboard terminal to Kalyan. All outgoing business had to be swung along the single “up” line to this point before diverging to various parts of the country; similarly all incoming traffic was converged upon this junction to reach the coast. Pressure due to traffic density was rapidly approaching the danger point, while the outlook was rendered additionally ominous from the discovery that the original lines were becoming tired from some fifty years’ service, necessitating the reduction of speed limits to a maximum of 40 miles an hour. Another outlet was impracticable; the solution lay in the increase of the carrying capacity of the existing artery, with the removal of such obstructions as experience had proved to be reacting against efficient economical working.

The necessary sanction for revitalizing the 34 miles of the trunk of the system was given in 1912. The first section to be reconstructed was between Bombay and Thana. Two new tracks were added, and as the task had to be completed “under traffic”, it presented the engineers with some pretty problems. Stations had to be remodelled or rebuilt, while all sidings had to be replanned. Nevertheless, the undertaking was successfully completed and brought into service in 1915. The improvement in the working of the traffic was immediate, but it only served to emphasize the necessity for overhauling the remaining 10 miles to Kalyan with all speed.

GREAT INDIAN PENINSULA RAILWAY BRIDGE OVER THE JUMNA AT KALPI. It has ten spans each of 250 feet, and a total length of 2,626 feet. The abutments are built for a double track, but only a single track has been laid with a road on the same level, thus providing for railway and highway traffic.

This second section was not so straightforward inasmuch as the additional tracks were not laid beside the original lines. The opportunity was taken to relocate the road between Thana and Kalyan to give more economical running and to effect a saving in distance. The original route followed the line of least resistance and so abounded with twists and turns. The new alignment not only avoids the first tunnel upon the old line, but drives direct through the obstruction of the Parsik height with a tunnel 4,300 feet in length -

While this improvement eased the situation very noticeably, it only served to throw into strong relief another weak link in the system; its existence had been appreciated for years, but had not been able to exert its restraining influence to the full owing to the throttling effect of the Bombay-

The only way out of the difficulty was to redesign the incline; but as this was certain to involve a huge expenditure, the task was deferred until every feasible expedient and possible measure of relief had been introduced and exhausted. The inevitable had then to be faced, and in October, 1913, the realignment of the Thull Ghaut incline was taken in hand. The task occupied five years, and the new road was brought into operation in September, 1918.

The new incline is just as remarkable a piece of work as its predecessor. It is of double-

Railway operation in India presents many problems without parallel in any other part of the world; conversely, it has also many factors reacting against the steady, rhythmic and uneventful movement of the diversity of traffic incidental to such a huge, thickly populated country. The most disturbing single influence is the recurrence of famine and plague due to the indifferent means of communication, other than the railway, for the prompt movement of grain from those districts in which it is abundant to those where a scarcity exists.

The Great Indian Peninsula Railway was brought full tilt against the significance of famine and its influence upon operation three years after the opening of the line to Raichur. The grim spectre was stalking through the Madras Presidency, and yet, at that very moment, the stations on the other divisions were bowed down with the yield from bounteous harvests. The railways strove desperately to mitigate the plight of the unhappy people, turning every wagon to this humane service, but the congestion which ensued became so acute as to slow down the movement to an exasperating degree.

Within two months every terminal station of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, from Jubbulpore to Raichur, was crowded with trains of wagons laden with grain, but they could not be sent forward, because the only available rails were those of the Great Indian Peninsula via Kalyan. The Madras Railway, which connects with the Great Indian Peninsula at Raichur, at that time could not handle more than too wagons a day, whereas the capacity of the Great Indian Peninsula system was practically unlimited. The congestion became so acute that the “down” line between Kalyan and Neral had to be converted into a siding, presenting the remarkable spectacle of 21 miles of grain-

Four years later the company had another spirited wrestle with famine conditions, and the exacting concomitant effects upon general traffic. Again a powerful demonstration of the indispensability of the railway, and the effective manner in which it can mitigate the terrible consequences of such an affliction by rapid transport were brought home to the community. The volume of grain moved as the result of the railway’s concentration of the whole of its available resources to the consummation of the great end was colossal, not only astonishing the authorities, but revealing the possible carrying capacity of the system to be far greater than had ever been anticipated.

THE GREAT INDIAN PENINSULA RAILWAY LINE OVER THE KALISINDH RIVER SUSPENDED IN MID-

Flood carried away about 300 feet of the embankment and left the rails, with the greater number of sleepers intact, depending in a graceful festoon across the breach.

In addition to transporting grain upon a gigantic scale, the railway, at the instigation of the Government, embarked upon elaborate new constructional work to provide employment for the stricken people. The cross-

The steel highway is exposed to many menaces, but in India it is assailed by one which, at times, asserts itself in the most devastating form -

During August, 1917, heavy rains fell in the state of Gwalior, charging the reservoir on Tigrah Lake, belonging to H.H. the Maharaja Scindia, to such a level that the masonry dam was subjected to an abnormal pressure. The wall gave way, and the released water rushed madly over the countryside, flooding an area of more than 40 square miles. Unfortunately the Great Indian Peninsula Railway was exposed to the full brunt of the water’s wild sweep. The embankment was breached at several places and the rails submerged at many points to a depth of 10 feet. When the flood subsided the engineers, by working night and day, succeeded in restoring the traffic after a suspension of three weeks.

By 1900 the mileage of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway had grown to 1,567½ miles, and the dawn of the new century ushered in the second era of its history. In the original charter of the railway there was one important clause. This was to the effect that the East India Company might, if it felt so disposed, purchase the whole network as it stood in 1900, in which year the original contract expired, by paying the value of the capital stock, according to its mean value upon the London Stock Exchange during the three previous years, either in a lump sum or by means of annuity.

The Secretary of State for India, to whom all the interests in the East India Company were transferred upon its extinction, exercised his option. The share capital of the undertaking was £20,000,000, with debenture capital to the approximate value of £6,000,000. The latter was taken over by the Secretary of State, while the former was valued at £34,859,217 17s. 6d. That is to say, every £100 in the original investment had appreciated to £174 5s. 11d. -

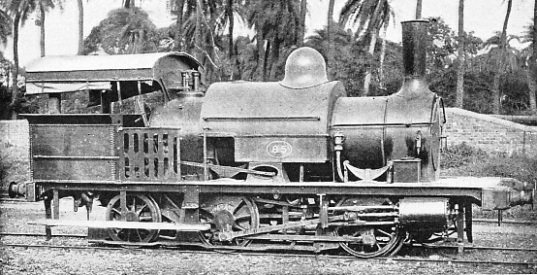

THE OLDEST LOCOMOTIVE -

You can read more on “Electrification Overseas”, “Modern Transport in India” and “The Railway Invasion of India 1” on this website.